|

HOPEWELL VILLAGE National Historic Site |

|

East wing of the Big House. This is the oldest wing,

built probably before 1770. In the lower right-hand corner are the bake

ovens.

Photo by Finch.

The Postwar Years

The fortunes of Mark Bird slid rapidly downhill after that. There was a flood on Hay Creek which ruined much of his property, and then came those postwar depression days when two or three Continental dollars would hardly buy a crust of bread. The furnace seems to have been out of operation in 1780 or 1781, for in the latter year Bird complained to the county that his "tax is too high, part of his iron work having not gone a long time;" and the tax records show that from 1782 through 1784, he paid only about one-fourth as much in taxes on his Hopewell properties as during the years immediately preceding and following. While 1783 appears to have been a good year from the standpoint of production, the years following were not. Between April 8 and September 14, 1784, only 196 tons of pig iron and 14-1/2 tons of finished castings were produced, and in 1785 there is record of only 134 tons of pig iron and 30-1/2 tons of finished castings.

In 1784, making a desperate effort to avoid the shoals of complete financial shipwreck, he borrowed 200,000 Spanish milled silver dollars from John Nixon, a wealthy Philadelphia merchant. The following year, through his brother-in-law, James Wilson, he tried to obtain from a group of financiers in Holland a long-term loan of 500,000 florin, indicating the value of his vast properties at 750,000 florin. Unsuccessful, his fate was sealed. Two years later, obliged to satisfy his debt, he assigned all his interests to Nixon. The Hopewell and Birdsboro properties were advertised for sheriff's sale in April 1788, and Bird moved to North Carolina. A letter written by him from there in 1807 to the celebrated Dr. Benjamin Rush, of Philadelphia, asking for financial assistance of friends (and medical advice from Dr. Rush for his rheumatism and sciatica) shows to what pathetic straits the once-powerful ironmaster was reduced. "There is no doubt my principle ruin was by the Warr & Depretiation," he wrote, and "I promise myself they [i. e., his friends] will not let me suffer, when they come to know of my Situation." Dr. Rush noted on the back of the letter: "Declined Soliciting relief for him as all his friends of 1776 were dead or reduced." Mark Bird died in comparative poverty. Thus he joined the long list of other once-powerful Pennsylvania ironmasters who went bankrupt, a list which, besides his own, included such names as Matthias Slough, Frederick Delaplank, John Truckenmiller, and Henry William Stiegel.

Following the failure of Mark Bird, Hopewell passed into the hands of James Old and Cadwalader Morris, who acquired two-thirds and one-third interest, respectively. Both were famous ironmasters. Old was the father-in-law of Robert Coleman, the ironmaster of Cornwall; and his son, William, married Elizabeth, the daughter of Henry William Stiegel. In 1790, Cadwalader Morris transferred his interest to his brother, Benjamin Morris, and in 1791 James Old did likewise. In 1793, however, deed to the entire property reverted to James Old, with Benjamin Morris holding the mortgage. The amount of the mortgage was 8,857 pounds, 14 shillings, and 5 pence, to be paid off in five annual installments.

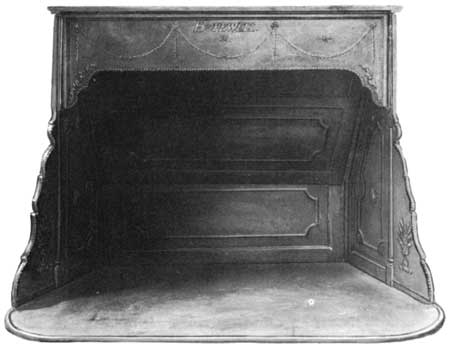

Hopewell "Franklin stove," or fireplace, of the

post-Revolutionary period.

For the next few years the furnace operated under the firm name of James Old & Co. With the youthful Matthew Brooke, who was appointed manager in 1794, in direct charge, attempts were made to put it back on a paying basis. Castings, especially stoves and hollow ware, were in great demand and prices were improving. But despite some recovery, Old was unable to meet his annual installments. In consequence, in 1800, he was forced to yield his title through the law to his creditor, Benjamin Morris, who promptly bought it at a sheriff's sale. That same year, in August, Morris sold the property for £10,000 to a partnership composed of Matthew Brooke and his brother, Thomas Brooke, and their brother-in-law, Daniel Buckley.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |