|

HOPEWELL VILLAGE National Historic Site |

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Guide to the Area

This guide is arranged to enable you to make your own tour of the area by following the numbers appearing on the sketch map on the preceding page. These numbers correspond with the numbers below, preceding descriptions of the most important physical remains, terrain features, and historic buildings on the site. Buildings and physical remains are indicated on the map in solid lines; sites of structures that no longer exist are shown in broken lines. While the tour suggested is the most convenient for covering all the points of interest, it need not be strictly followed, and you may select any other approach.

1. HOPEWELL FURNACE. The furnace was first built in 1770-71, rebuilt in 1828, and operated in all for 113 years, until 1883 when it was blown out for the last rime. It was a typical charcoal-burning, cold-blast furnace of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Its outer dimensions are 32 feet high and 22 feet square at the base and the bosh (largest dimension of the inner core) is 6-1/2 feet. With an average annual capacity of 700 tons, it was one of the largest furnaces of its time. Furnaces cast ingots of iron, called "pig iron" (which forges later refined into malleable iron for hardware, nails, etc.), stoves, hollow ware, and other products. The charge—iron ore, charcoal for fuel, and limestone for flux—was introduced in alternate layers through the tunnel head at the top; and the molten metal was "tapped" or run out through a hole in the damstone which was located directly under the casting arch. Like most eighteenth century furnaces, this one had but one tuyere (opening) for conveying the blast into the furnace. It is located directly under the tuyere arch, which faces the furnace bank. A blast pipe conducted the air from the bellows to the tuyere pipe, which was inserted into the tuyere. Generally, about 2-1/2 tons of ore and 180 bushels of charcoal were required to make 1 ton of iron. Hopewell Furnace operated throughout its history as a primitive eighteenth-century blast furnace, although in 1828 it was rebuilt and its top capacity, because of improved blast equipment, increased to 1,000 tons or more.

2. CAST HOUSE. The cast house, which is no longer in evidence, was a large frame structure situated directly in front of the casting arch and extended eastward from the furnace. Inside were the casting beds of sand—a pattern of gutters called "sows" and "pigs"—into which the molten metal flowed from the main gutter or runner. Finished castings such as stoves and hollow ware were made in the northern part of the building, called the "moulding room."

3. ORE ROASTER. Built in 1882, or a year before the furnace closed down, the ore roaster was a cylindrical structure of boiler plate about 12 feet high. The masonry base of the roaster may be seen just south of the wall which extends from the furnace bank to the office. Ore was dumped into the top along with anthracite coal, charcoal, or wood (for fuel), and after roasting, came out the bottom. The masonry mound served to spread the roasted ore onto the flat stones on the ground. Roasting, or calcination, of some types of ore was necessary to rid the ore of impurities and to loosen its texture for better smelting.

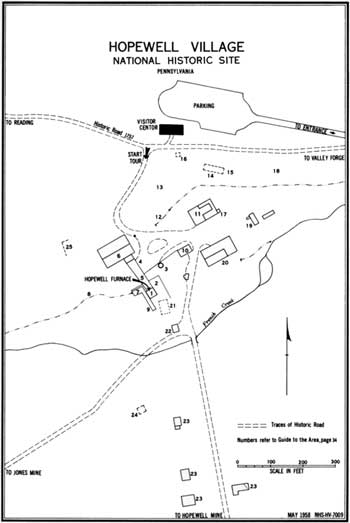

Furnace bank, Hopewell Furnace, and portion of

charcoal house as they appeared in 1949.

Photo by

Finch.

4. FURNACE BANK. This was perhaps the most conspicuous and important terrain feature of a typical eighteenth-century iron-making community. Before the days of steam and electricity, furnaces were usually built close to a bank to provide a practical means of access to the furnace top, over a connecting bridge. This was the destination for the wagons hauling ore, charcoal, and limestone to the furnace. Here stood the charcoal house, and it was here that boys employed by the furnace riddled the ore. Prices for furnace products were often quoted in terms of "at the Bank" or "on the Bank." Along with the cast house below, the furnace bank was the scene of greatest activity.

5. BRIDGE HOUSE. A solid frame structure, the bridge house consisted of two parts: an open-sided shed leading from the entrance to the charcoal house to the end of the bank, and a covered bridge spanning the space between the bank and the furnace. Charcoal wagons pulled into the shed as they arrived from the "pits" with their charcoal, ready for un loading. Over the bridge, "fillers" carried or carted in baskets the charge to the tunnel head. In the bridge house, too, were kept the ore and limestone bins, filled and ready for instant use, as well as the scales for measuring the charge.

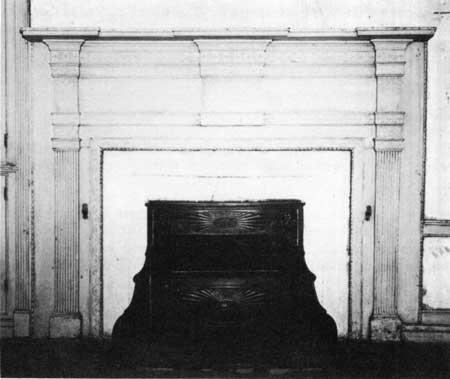

Hand-carved mantelpiece and "Franklin stove" in

the dining room of the Big House.

Photo by Finch.

6. CHARCOAL HOUSE. The "Coal House," as the name implies, was for the storage of charcoal. Charcoal was originally called "coal" and what we now know as coal was called "stone coal." Substantially rebuilt in 1880 with a capacity of 55,000 bushels, it held enough charcoal to operate the furnace for about 3 months. Charcoal was stored inside to keep it from deteriorating in the weather.

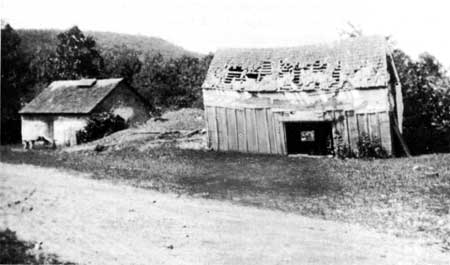

Ruins of Hopewell wheelwright shop in 1895. To the

left is the blacksmith shop and in the foreground, the old section of

the Birdsboro-Warwick Road.

Courtesy Chester County Historical

Society.

7. WATERWHEEL-BLAST MACHINERY. The wheel, 22 feet in diameter, is turned by water from Hopewell Lake brought by the West Head Race. The wheel operates the blast machinery above it. The two tubs are double acting cylinders, with pistons which compress air. The compressed air is transferred by a system of valves into the rectangular receiving box between the tubs. From the box, the air enters the bottom of the furnace through the copper pipe. Air pressure was needed both to make a hotter fire and to supply additional oxygen. The machinery produces about three-quarters of a pound of air per square inch. The wheel and blast machinery were restored by the National Park Service in 1952.

8. WEST HEAD RACE. Water to drive the wheel is obtained from nearby streams by means of ditches or races. The West Head Race, one-quarter of a mile long, extends from Hopewell Lake (formerly the smaller furnace pond) to the wheel pit. It was restored in 1952.

9. TAIL RACE. The stone-lined ditch in the rear of the furnace connecting with the wheel pit carries the spent water from the wheel back into French Creek. It goes underground a few feet south of the furnace and emerges again 400 feet to the east, near the southeast corner of the barn, from where it leads into the creek.

Springhouse and lard kitchen, one of several

outbuildings associated with the Big House.

Photo by

Finch.

10. OFFICE AND STORE. This is one of the best-preserved buildings, as well as one of the oldest. It probably formed a part of the original village at the time the furnace was built, for references to it have been found as far back as 1784. It was used as a combination furnace office and plantation store. The west room on the main floor (containing the built-in safe) served as the office. Here were kept the records of ore and charcoal used, pig iron cast and sold, orders for stoves and other furnace products, wages paid for labor, and all the other bookkeeping details of the iron-making business in the early days. In the east room was the store where drygoods, groceries, and other items were sold to the furnace workers on a credit basis.

11. BIG HOUSE. This large house was the residence of the ironmasters or their managers. It was popularly referred to as the "Big House," in contrast with the small tenant houses in which the workmen lived. Built in the form of a "T," in three stages, it underwent some change in the nineteenth century. The rear section—the stem of the "T"—is the oldest and probably was already standing in 1770 when the furnace was built. The "steps" on the roof the long front porch and floor-length windows, and the bathroom over the north porch, are mid-nineteenth century and even later additions. Altogether the house contains 14 rooms, bath, hall way, and 2 cellars. Most interesting features of the interior are the main staircase and the mantelpiece in the dining room, both hand-carved. The house is not yet furnished, although a nucleus of its early furnishings is already on hand. This consists of late Empire and Victorian beds, wardrobes, tables and chairs, a piano, a sideboard, and a few other objects. Practically every ironmaster from Mark Bird to Dr. Charles M. Clingan lived in the Big House at one time or another. Despite long and continuous use, it is still in excellent state of preservation.

Restored furnace, bridge house, furnace bank, and

walls as they appeared in 1958.

12. EAST HEAD RACE. To the north of the Big House, separating it from the larger portion of the gardens, is the East Head Race. About a mile long, beginning in the Baptism Creek area to the east and ending near the Birdsboro-Warwick Road just west of the Big House, this race, as well as the West Head Race, supplied water to the furnace wheel. Considerable portions of this race have been restored.

13. GARDEN. To the north of the mansion, extending up the hillside, was once a semiformal garden, with old-fashioned flowers, boxwood, trelliswork, walks, a combination summerhouse and icehouse, greenhouse, and gardener's toolhouse. The path from the mansion to the parking lot is the site of the historic path. A row of boxwood screened the garden from the road above, and the garden was surrounded by a whitewashed picket fence. There was also a vegetable garden here to supply the mansion with vegetables.

14. GREENHOUSE. The ruins of the greenhouse are clearly visible on the hillside. It was probably built about 1850. It contained two sections—one a grapery and the other a hothouse for flowers.

15. GARDENER'S TOOL HOUSE. It once stood just off the southeast corner of the greenhouse.

16. SUMMERHOUSE. A slight depression near the top of the hillside to the right of the path now marks the site of the summerhouse. Underneath was the icehouse. The earliest reference to an icehouse in Hopewell records is for 1833. The ice probably came from the old furnace pond, now the site of Hopewell Lake.

17. BAKE OVENS. Restored in 1955, the two ovens were probably used for community baking. They stand near the southeast corner of the mansion. One was first built in 1824, and the other in 1842. The shingle roof protected the baker standing at the oven door.

18. ORCHARD. East of the gardens and extending along the hillside for a distance was an apple orchard which provided the people with much of their fruit, cider, and apple butter. There were three orchards at Hopewell in the early days (one of them a peach orchard) and this one was probably the oldest.

19. SPRINGHOUSE. The cool water of springs was widely utilized in former times for preserving food. The springhouse was generally a small stone structure with a roof over it, built around a nearby spring which was deepened and widened to form a springbox and trough. Hopewell's springhouse was larger than most, containing three rooms. The northernmost one has the spring box for catching the flow and the center one the cooling troughs where dairy products and other perishables were kept in partially submerged crocks. The southernmost room, the "lard kitchen" with its huge fireplace, is actually not a part of the springhouse but rather a structure added to it in a later period. The heavy accumulation of oil and soot in the fireplace indicates that many kettles of lard, apple butter, and soap must have simmered here through the years. The cement floors probably date from the 1870's.

20. BARN. The barn now in evidence is a new one, built about 1928— before the Federal Government acquired the site. But portions of the historic walls, incorporated into the new one, can be seen from the inside. Below were the stables for draft animals and cattle. The present structure is used to house the fine Edward Brooke collection of late nineteenth-century carriages.

21. WHEELWRIGHT SHOP. Nothing remains of this building, which once stood between the furnace and the blacksmith shop. A frame structure with an attic, it was about 15 feet wide and 20 feet long. In the shop were a workbench fitted with wooden tools, a shaving horse, a pit in the floor for the turning of the wheel as spokes were fitted into the hub which rested on blocks, an old wood stove, the usual reamers for making hubs, and all the customary tools found in a typical carpenter and wheel wright shop of the early days.

22. BLACKSMITH SHOP. This small stone building standing near the wooden bridge which spans French Creek was built sometime after 1770 and before 1780. Here the work animals were shod and simple hardware and furnace tools made and repaired. The old stone forge, leather hand-bellows, pole-lever wood drill press, and wooden crane, as well as hand tools, are to be seen within the shop. Not all of these are original, however. The blacksmith was an important artisan in early America, doubly important at furnaces where, in addition to his regular duties, he often had to make mechanical repairs to furnace equipment.

23. TENANT HOUSES. The four stone houses along the Birdsboro-Warwick Road (the one standing by itself was once used as a boarding house) were among the many which ironmasters provided for their workmen. Others stood along this and other roads leading into the village, as well as scattered about in the surrounding wooded area and at the mine holes. Most of them were rude log cabins, however. All of them were of simple construction and furnished with the barest essentials. The largest of the four (the duplex) is obviously the newest, probably built near the middle of the nineteenth century.

24. SCHOOLHOUSE. The site of Hopewell's old schoolhouse is marked by a slight depression ringed with an irregular heap of rocks now grown over with trees, on the south side of Joanna Road and to the rear of the first tenant house. It was a typically old-fashioned stone schoolhouse, one and a half stories high and approximately 30 feet square, accommodating 35 to 40 pupils. Built in 1836 by the ironmaster, at the height of Hopewell's prosperity, it was last used in 1870.

25. ANTHRACITE FURNACE. By wandering into the woods for a short distance, near the northwest corner of the charcoal house, you will find the ruins of an experimental anthracite furnace—the first and only attempt at Hopewell to convert from the use of charcoal to anthracite in the smelting of iron. Built in 1849 by Clement Brooke, the ironmaster, it proved unprofitable and 3 years later was moved to Monocacy. Large portions of the sandstone inner-lining are exposed to view, revealing the glazing effects of intense heat.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |