|

GETTYSBURG National Military Park |

|

"The Battle of Gettysburg" (Pickett's Charge), Peter F. Rothermel.

Courtesy Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

ON THE GENTLY ROLLING FARM LANDS surrounding the little town of Gettysburg, Pa., was fought one of the great decisive battles of American history. For 3 days, from July 1 to 3, 1863, a gigantic struggle between 75,000 Confederates and 97,000 Union troops raged about the town and left 51,000 casualties in its wake, Heroic deeds were numerous on both sides, climaxed by the famed Confederate assault on July 3 which has become known throughout the world as Pickett's Charge. The Union Victory gained on these fields ended the last Con federate invasion of the North and marked the beginning of a gradual decline in Southern military power.

Here also, a few months after the battle, Abraham Lincoln delivered his classic Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the national cemetery set apart as a burial ground for the soldiers who died in the conflict.

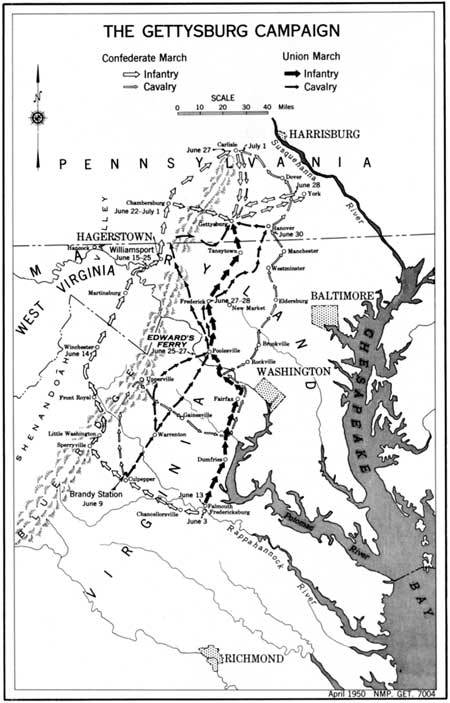

The Situation, Spring 1863

The situation in which the Confederacy found itself in the late spring of 1863 called for decisive action. The Union and Confederate armies had faced each other on the Rappahannock River, near Fredericksburg, Va., for 6 months, The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Gen. R. E. Lee, had defeated the Union forces at Fredericksburg in December 1862 and again at Chancellorsville in May 1863, but the nature of the ground gave Lee little opportunity to follow up his advantage. When he began moving his army westward, on June 3, he hoped, at least, to draw his opponent away from the river to a more advantageous battleground. At most, he might carry the war into northern territory, where supplies could be taken from the enemy and a victory could be fully exploited. Even a fairly narrow margin of victory might enable Lee to capture one or more key cities and perhaps increase northern demands for a negotiated peace.

Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, Commander of the Union Forces at Gettysburg. Courtesy National Archives. |

Gen. Robert E. Lee, Commander of the Confederate Army at Gettysburg. Courtesy National Archives. |

Confederate strategists had considered sending aid from Lee's army to Vicksburg, which Grant was then besieging, or dispatching help to General Bragg for his campaign against Rosecrans in Tennessee. They concluded, however, that Vicksburg could hold out until climatic conditions would force Grant to withdraw, and they reasoned that the eastern campaign was more important than that of Tennessee.

Both Union and Confederate governments had bitter opponents at home. Southern generals, reading in Northern newspapers the clamors for peace, had reason to believe that their foe's morale was fast weakening. They felt that the Army of Northern Virginia would continue to demonstrate its superiority over the Union Army of the Potomac and that the relief from constant campaigning on their own soil would have a happy effect on Southern spirit. Events were to prove, however, that the chief result of the intense alarm created by the invasion was to rally the populace to better support of the Union government.

(click on map for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |