|

GETTYSBURG National Military Park |

|

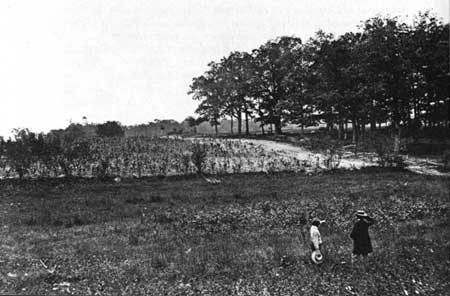

McPherson Ridge and Woods, the Federal position on July 1. In the woods

at the right, General Reynolds was killed. The cupola of the Theological

Seminary appears in the background.

Brady photograph.

The First Day (continued)

THE BATTLE OF OAK RIDGE. While the initial test of strength was being determined west of Gettysburg by advance units, the main bulk of the two armies was pounding over the roads from the north and south, converging upon the ground chosen by Buford. Rodes' Confederates, hurrying southward from Carlisle to meet Lee at Cashtown, received orders at Biglerville to march to Gettysburg. Early, returning from York with Cashtown as his objective, learned at Heidlersburg of the action at Gettysburg and was ordered to approach by way of the Harrisburg Road.

Employing the wooded ridge as a screen from Union cavalry north of Gettysburg, Rodes brought his guns into position on Oak Ridge about 1 o'clock and opened fire on the flank of Gen. Abner Doubleday, Reynolds' successor, on McPherson Ridge. The Union commander shifted his lines northeastward to Oak Ridge and the Mummasburg Road to meet the new attack. Rodes' Confederates struck the Union positions at the stone wall on the ridge, but the attack was not well coordinated and resulted in failure. Iverson's brigade was nearly annihilated as it made a left wheel to strike from the west. In the meantime, more Union troops had arrived on the field by way of the Taneytown Road. Two divisions of Howard's Eleventh corps were now taking position in the plain north of the town, intending to make contact with Doubleday's troops on Oak Ridge.

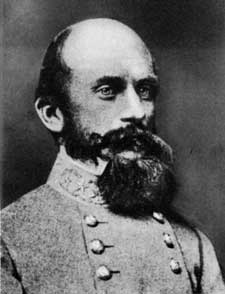

Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, Courtesy National Archives. |

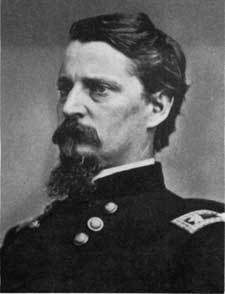

Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, Courtesy National Archives. |

Doles' Confederate brigade charged across the plain and was able to force Howard's troops back temporarily, but it was the opportune approach of Early's division from the northeast on the Harrisburg Road which rendered the Union position north of Gettysburg indefensible. Arriving in the early afternoon as the Union men were establishing their position. Early struck with tremendous force, first with his artillery and then with his infantry, against General Barlow. Soon he had shattered the entire Union force. The remnants broke and turned southward through Gettysburg in the direction of Cemetery Hill. In this headlong and disorganized flight General Schimmelfenning was lost from his command, and, finding refuge in a shed, he lay 2 days concealed within the Confederate lines. In the path of Early's onslaught lay the youthful Brigadier Barlow severely wounded, and the gallant Lieut. Bayard Wilkeson, whose battery had long stood against overwhelming odds, mortally wounded.

The Union men on Oak Ridge, faced with the danger that Doles would cut off their line of retreat, gave way and retired through Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill. The withdrawal of the Union troops from the north and northwest left the Union position on Mcpherson Ridge untenable. Early in the afternoon, when Rodes opened fire from Oak Hill, Heth had renewed his thrust along the Chambersburg Pike. His troops were soon relieved and Pender's division, striking north and south of the road, broke the Union line. The Union troops first withdrew to Seminary Ridge, then across the fields to Cemetery Hill. Here was advantageous ground which had been selected as a rallying point if the men were forced to relinquish the ground west and north of the town. Thus, by 5 o'clock, the remnants of the Union forces (some 6,000 out of the 18,000 engaged in the first day's struggle) were on the hills south of Gettysburg.

Scene north of Gettysburg from Oak Ridge. The Federal position may

he seen near the edge of the open fields in the middle distance.

Ewell was now in possession of the town, and he extended his line from the streets eastward to Rock Creek. Studiously observing the hills in his front, he came within range of a Union sharpshooter, for suddenly he heard the thud of a minie ball. Calmly riding on, he remarked to General Gordon at his side, "You see how much better fixed for a fight I am than you are. It don't hurt at all to be shot in a wooden leg."

A momentous decision now had to be made. Lee had reached the field at 3 p. m., and had witnessed the retreat of the disorganized Union troops through the streets of Gettysburg. Through his glasses he had watched their attempt to reestablish their lines on Cemetery Hill. Sensing his advantage and a great opportunity, he sent orders to Ewell by a staff officer to "press those people" and secure the hill (Cemetery Hill) if possible. However, two of Ewell's divisions, those of Rodes and Early, had been heavily engaged throughout the afternoon and were not well in hand. Johnson's division could not reach the field until late in the evening, and the reconnaissance service of Stuart's cavalry was not yet available. General Ewell, uninformed of the Union strength in the rear of the hills south of Gettysburg, decided to await the arrival of Johnson's division. Cemetery Hill was not attacked, and Johnson, coming up late in the evening, stopped at the base of Culp's Hill. Thus passed Lee's opportunity of July 1.

When the Union troops retreated from the battleground north and west of the town on the evening of July 1, they hastily occupied defense positions on Cemetery Hill, Culp's Hill, and a part of Cemetery Ridge. Upon the arrival of Slocum by the Baltimore Pike and Sickles by way of the Emmitsburg Road, the Union right flank at Culp's Hill and Spangler's Spring and the important position at Little Round Top on the left were consolidated. Thus was developed a strong defensive battle line in the shape of a fish hook, about 3 miles long, with the advantage of high ground and of interior lines. Opposite, in a semi-circle about 6 miles long, extending down Seminary Ridge and into the streets of Gettysburg, stood the Confederates who, during the night, had closed in from the north and west.

Spangler's Spring, the right of the Federal battle line, July 2

and 3.

This Tipton photograph shows the wartime appearance

of the spring.

The greater part of the citizenry of Gettysburg, despite the prospect of battle in their own yards, chose to remain in their homes. Both army commanders respected noncombatant rights to a marked degree. Thus, in contrast with the fields of carnage all about the village, life and property of the civilian population remained unharmed, while the doors of churches, schools, and homes were opened for the care of the wounded.

General Meade, at Taneytown, had learned early in the afternoon of July 1 that a battle was developing and that Reynolds had been killed, A large part of his army was within 5 miles of Gettysburg. Meade then sent General Hancock to study and report on the situation. Hancock reached the field just as the Union troops were falling back to Cemetery Hill. He helped to rally the troops and left at 6 o'clock to report to Meade that in his opinion the battle should be fought at Gettysburg. Meade acted on this recommendation and immediately ordered the concentration of the Union forces at that place. Meade himself arrived near midnight on July 1.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |