|

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON An Appreciation of the Man and his Times |

|

A MAN FOR THE TIMES

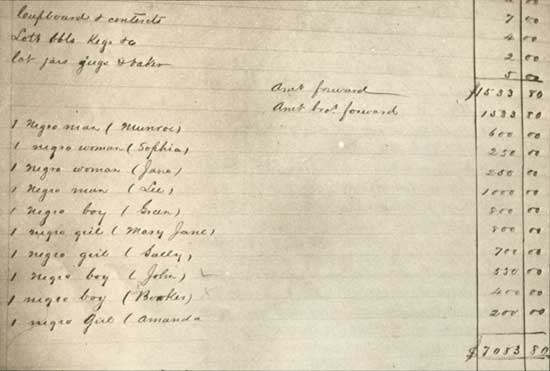

The slave who would later call himself Booker Taliaferro Washington was born April 5, 1856, on a small tobacco plantation in the back country of Franklin County, Va. On the 1861 plantation inventory he was listed, along with his late owner's cattle, tools, and furniture, as "1 negro boy (Booker)," and valued at $400. ("Booker" was as much of a name as the 5-year-old slave boy had.) His mother, "1 negro woman (Jane) . . . $250.00," was the plantation cook; her childbearing years were over, and she was worth little at a time when a prime field-hand brought more than $1,000. A half-brother and half-sister were also listed, but Booker's father was not. In all probability, he was the shiftless white son of a neighboring farmer named Ferguson. His child never knew him.

|

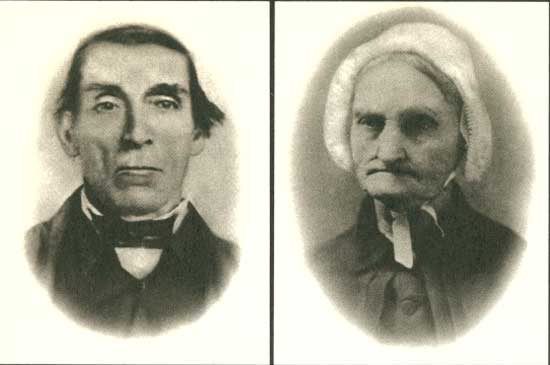

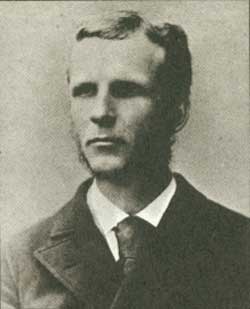

| James (left) and Elizabeth (right) Burroughs. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

The 207-acre plantation on which Booker was born and spent his childhood years consisted of a plain log house, a few head of livestock, and about 10 slaves. It was typical of the region—a stark contrast to the now - popular image of the extensive and luxurious Old South estate. The owner was James Burroughs, whose wife Elizabeth bore him 14 children. With only two of his slaves adult male fieldhands, Burroughs and his sons were no strangers to hard labor. Production of tobacco and the subsistence crops for master, slave, and livestock left little leisure for anyone.

"My life had its begining in the midst of the most miserable, desolate, and discouraging surroundings."

Booker T. Washington

The Burroughs family enjoyed few comforts, and for their slaves, life was a bare existence indeed. Washington vividly recalled the ramshackle cabin in which he spent 9 years in slavery:

The cabin was not only our living-place, but was also used as the kitchen for the plantation. . . . The cabin was without glass windows; it had only openings in the side which let in the light, and also the cold, chilly air of winter. There was a door to the cabin— that is, something that was called a door— but the uncertain hinges by which it was hung, and the large cracks in it, to say nothing of the fact that it was too small, made the room a very uncomfortable one. . . . Three children—John, my older brother, Amanda, my sister, and myself—had a pallet on the dirt floor, or, to be more correct, we slept in and on a bundle of filthy rags laid upon the dirt floor.

|

| "1 negro boy (Booker)..." The 1861 Burroughs property inventory also lists his mother Jane, his brother John, and his sister Amanada. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

The slave child's diet was in keeping with the quality of his living accommodations. As Washington remembered it,

meals were gotten by the children very much as dumb animals get theirs. It was a piece of bread here and a scrap of meat there. It was a cup of milk at one time and some potatoes at another.

"One of my earliest recollections," he wrote, "is that of my mother cooking a chicken late at night, and awakening her children for the purpose of feeding them. How or where she got it I do not know."

As might be expected, clothing worn by slaves was of the poorest sort. Adults often wore the master's cast-offs, but the children's only garments were commonly knee-length shirts woven from rough flax. Washington called wearing this shirt "the most trying ordeal that I was forced to endure as a slave boy" and compared its discomfort to "the feeling that one would experience if he had a dozen or more chestnut burrs, or a hundred small pin-points, in contact with his flesh."

Though life for the Burroughs' slaves was hard, there was not the harsh cruelty often found on the larger plantations managed by overseers. With the master and his family working alongside the slaves, there was a feeling of belonging—of sharing in the family's joys and sorrows. Booker was too young for heavy work but was kept busy with such tasks as could be performed by a small boy. Among his chores were carrying water to the men in the fields, taking corn to the nearby mill for grinding, and fanning the flies from the Burroughs' dining room table.

For Booker, the worst aspect of slavery was its suppression of a child's natural desire to learn. Teaching a slave to read and write was prohibited by law in Virginia, as it was throughout most of the South. On occasion, Booker would accompany one of the Burroughs' daughters to the door of a nearby common school. "The picture of several dozen boys and girls in a schoolroom made a deep impression upon me," he later wrote, "and I had the feeling that to get into a schoolhouse and study in this way would be about the same as getting into paradise."

The Civil War years were a time of hardship for the Burroughs family. James Burroughs died in 1861. With her sons in the Confederate army, his widow found it difficult to maintain the plantation. What simple luxuries the family had normally enjoyed—coffee, tea, sugar—were no longer available in wartime. Two of the Burroughs boys lost their lives in the conflict, and two others were wounded.

But for the slaves, the war was a source of hushed excitement and expectation. Washington wrote:

When war was begun between the North and the South, every slave on our plantation felt and knew that, though other issues were discussed, the primal one was that of slavery. Even the most ignorant members of my race on the remote plantations felt in their hearts, with a certainty that admitted of no doubt, that the freedom of the slaves would be the one great result of the war, if the Northern armies conquered.

Booker himself first became aware of the situation one morning before daybreak when "I was awakened by my mother kneeling over the children and fervently praying that Lincoln and his armies might be successful, and that one day she and her children might be free."

Jane's prayer was answered in April 1865 after the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, some 60 miles from the Burroughs plantation. When the slaves had gathered in front of the Burroughs house, Washington recalled, "some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased."

"I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life, as by the obstacles which he has overcome while trying to succeed."

Booker T. Washington

Unlike most slaves, Booker and his family were fortunate in having a place to go when their freedom was proclaimed. During the war, Booker's stepfather had escaped to Malden, W.Va., where he obtained work in a salt furnace. After emancipation he sent for his family to join him there.

Despite the fact of freedom, physical conditions at Malden were even worse than on the plantation. Nine-year-old Booker was put to work in the salt furnace, often starting at 4 o'clock in the morning. A few years later, he labored as a coal miner, hating the darkness and danger of the work. Home was a crowded shack in the squalor of Malden's slums.

|

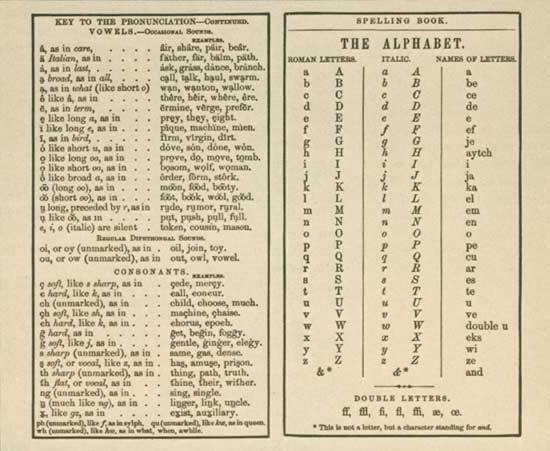

| Pages from Webster's Elementary Spelling-Book called the "blue-black speller" because of the book's blue-cloth cover. Booker learned the alphabet from painstaking study of this book. |

The trials of Booker's new life, far from discouraging him, stimulated his desire for education. His mother sympathized with his longing, and managed to get him a copy of Webster's "blue-back" spelling book.

I began at once to devour this book, and I think that it was the first one I ever had in my hands. I had learned from somebody that the way to begin to read was to learn the alphabet, so I tried in all the ways I could think of to learn it,—all of course without a teacher, for I could find no one to teach me. . . . In some way, within a few weeks, I had mastered the greater portion of the alphabet.

Bitter disappointment came when a school for Negroes opened in Malden and Booker's stepfather would not let him leave work to attend. But Booker arranged with the teacher to give him lessons at night. Later he was allowed to go to school during the day "with the understanding that I was to rise early in the morning and work in the furnace till nine o'clock, and return immediately after school closed in the afternoon for at least two more hours of work." Noting that his classmates all had two names, Booker adopted the surname "Washington." He would add the "Taliaferro" later when he learned that it was part of the name given to him by his mother shortly after his birth.

The strongest influence shaping Washington's character at Malden was Viola Ruffner, Vermont-born wife of the owner of the salt furnace and coal mine. In 1871 Washington became her houseboy and was thoroughly indoctrinated in the puritan ethic of cleanliness and hard work. Thirty years later Washington stated, "the lessons that I learned in the home of Mrs. Ruffner were as valuable to me as any education I have ever gotten anywhere since."

"There is no education which one can get from books and costly apparatus that is equal to that which can be gotten from contact with great men and women."

Booker T. Washington

While working in the coal mine, Washington overheard two miners talking about a large school for Negroes at Hampton, Va. With no clear idea of where it was or how he would get there, he resolved somehow to attend this school.

|

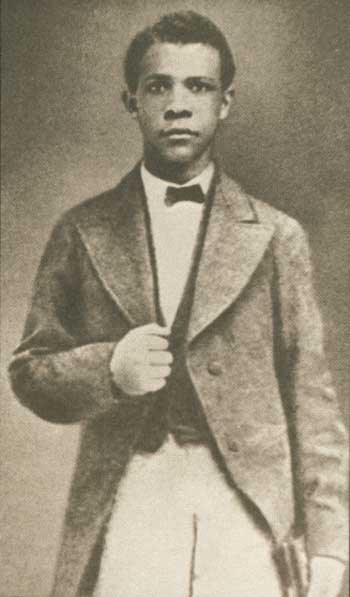

| Booker T. Washington, about the time he attended Hampton Institute. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

In the autumn of 1872, when he was 16 years old, Washington set out on the 400-mile journey to Hampton. An early experience with discrimination occurred on this trip—he was refused food and lodging at a "common, unpainted house called a hotel" and spent the cold night walking about to keep warm. Begging rides and traveling much of the way on foot, Washington arrived penniless in Richmond, 80 miles short of his destination. He worked there for several days to get money so he could continue his trip. He slept under a board sidewalk.

Washington was so dirty and ragged upon reaching Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute that the head teacher was reluctant to admit him. When he persisted, she finally asked him to sweep one of the classroom floors. Recalling his training at the hands of Mrs. Ruffner, Washington cleaned the entire room thoroughly.

I had the feeling that in a large measure my future depended upon the impression I made upon the teacher in the cleaning of that room. . . . When she was unable to find one bit of dirt on the floor, or a particle of dust on any of the furniture, she quietly remarked, "I guess you will do to enter this institution."

|

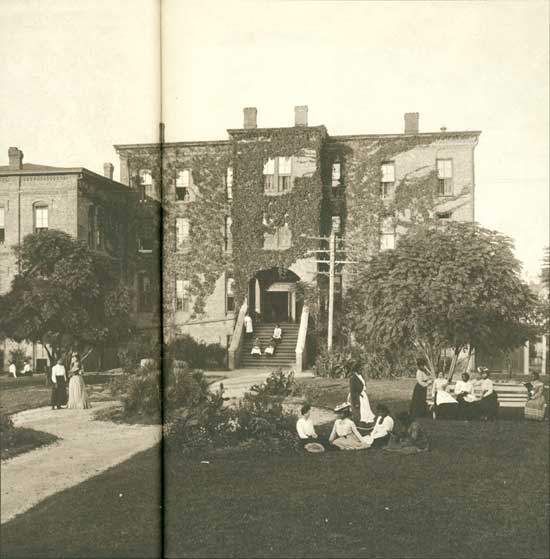

| Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Hampton, Va. What Washington learned here he would later put to use at Tuskegee. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

Washington studied at Hampton Institute for 3 years, working as a janitor to earn his board. His experience there influenced him profoundly. Hampton's emphasis on vocational training in industry, agriculture, and teaching was a revelation to him:

Before going there I had a good deal of the then rather prevalent idea among our people that to secure an education meant to have a good, easy time, free from all necessity for manual labour. At Hampton I not only learned that it was not a disgrace to labour, but learned to love labour, not alone for its financial value, but for labour's own sake and for the independence and self-reliance which the ability to do something which the world wants done brings.

|

| Gen. Samuel C. Armstong, Hampton's founder and principal. Washington called him "a perfect man". (Hampton Institute, Office of Public Relations) |

Of equal importance was Washington's association with the dedicated, selfless teachers of Hampton—particularly with Gen. Samuel C. Armstrong, principal of the school. Like many of the teachers, Armstrong had gone south after the Civil War with a missionary zeal to uplift the newly freed slaves. His philosophy of practical education and his strength of character made a lasting impression on the young student. Years later, Washington called Armstrong "a great man—the noblest, rarest human being that it has ever been my privilege to meet."

"Knowledge will benefit little except as it is harnessed, except as its power is pointed in a direction that will bear upon the present needs and condition of the race."

Booker T. Washington

After graduating with honors from Hampton in 1875, Washington returned to Malden to teach elementary school. Here an incident impressed him with the importance of using practical demonstrations in education. His pupils displayed little interest in a classroom geography lesson on islands, bays, and inlets. But during recess, while they were playing by the edge of a creek, the boy who was "most dull in the recitation" pointed out these features among the rocks and tufts of grass. The animated response of the class gave Washington a teaching lesson he never forgot.

|

| The Class of 1875 of Hampton Institute. Washington is seated second fom the left in the first row. (Hampton Institute, Office of Public Relations) |

Two years later, Washington went to the Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., where he studied for 8 months. There he was able to compare the value of academic education to that of vocational training:

At Hampton the student was constantly making the effort through the industries to help himself, and that very effort was of immense value in character-building. The students at the other school seemed to be less self-dependent. . . . In a word, they did not appear to me to be beginning at the bottom, on a real, solid foundation, to the extent that they were at Hampton. They knew more about Latin and Greek when they left school, but they seemed to know less about life and its conditions as they would meet it at their homes.

At General Armstrong's request, Washington returned to Hampton in 1879 as an instructor and "house father" for 75 Indian youths being trained at the Institute. Armstrong was highly impressed with Washington's ability. In May 1881, the principal received a letter from a group in Tuskegee, Ala., asking him to recommend a man to start a Negro normal school there. The group appeared to expect a white man for the job. Armstrong replied that he could suggest no white man, but that a certain Negro would be well qualified. The answer came by telegram: "Booker T. Washington will suit us. Send him at once."

"From the very outset of my work, it has been my steadfast purpose to establish an institution that would provide instruction not for the select few, but for the masses, giving them standards and ideals, and inspiring in them hope and courage to go patiently forward."

Booker T. Washington

On July 4, 1881, at the age of 25, Washington founded Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. The obstacles facing him were formidable. While the State of Alabama had appropriated $2,000 for teachers' salaries, no provision had been made for land, buildings, or equipment. Washington reported:

the most suitable place that could be secured seemed to be a rather dilapidated shanty near the coloured Methodist church, together with the church itself as a sort of assembly-room. Both the church and the shanty were in about as bad condition as was possible. . . . whenever it rained, one of the older students would very kindly leave his lessons and hold an umbrella over me while I heard the recitations of the others.

|

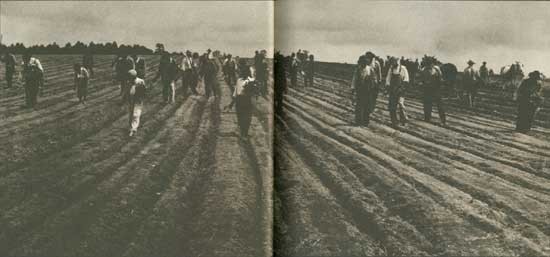

| Under Washington's firm guidance, Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in his own lifetime grew from a small collection of dilapidated buildings (top) and 30 students to a 2,000-acre campus of 107 buildings, more then 1,500 students, and nearly 200 faculty members. The students themselves constructed most of the school's buildings. (Top: Booker T. Washington National Monument; Bottom: Library of Congress) |

Washington found, too, that his notions of practical education ran counter to those of many parents and prospective students with whom he talked. They saw education solely as "book learning" which would allow the student to escape labor—a view with which Washington had little sympathy. As he toured the Alabama countryside surveying the poverty and squalor prevalent among his race, he became increasingly convinced that economic advancement through vocational training was the essential first step forward for the black masses. Later Washington summarized this philosophy:

I would teach the race that in industry the foundation must be laid—that the very best service which any one can render to what is called the higher education is to teach the present generation to provide a material or industrial foundation. On such a foundation as this will grow habits of thrift, a love of work, economy, ownership of property, bank accounts. Out of it in the future will grow practical education, professional education, positions of public responsibility.

As Washington saw it, trained labor would lead to economic prosperity, and economic prosperity to full citizenship and equal participation in American life.

|

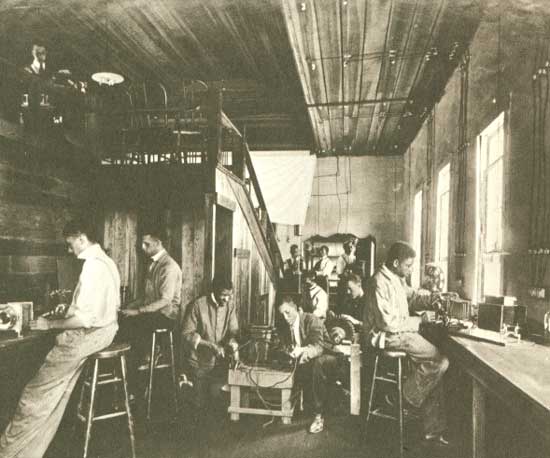

| Washington expected each student who attended Tuskegee to acquire a practical knowledge of some one trade "together with the spirit of industry, thrift and economy, that they would be sure of knowing how to make a living after they had left us." (Library of Congress) |

Tuskegee Institute opened with 30 students selected chiefly for their potential as teachers. Though the students had some prior education, they had little appreciation for the virtues of personal and household cleanliness so valued by their instructor. Washington keenly felt the need for on-campus dormitories so the students' living habits might be supervised and improved. There also was no land or facility with which to teach manual skills and furnish a means for the students to earn their expenses.

|

| Making mattresses. All the mattresses and pillows used at the Institute were made by the students. (Library of Congress) |

To meet these needs, the school soon acquired an abandoned farm nearby. The property had no buildings suitable for classrooms or dormitories. But through Washington's efforts, enough money was raised for construction materials, and the students erected the first brick building. After repeated failures the students built a kiln, and they learned to manufacture bricks for future buildings and public sale. The "learning by doing" approach was carried over into agricultural education on the school land, where students raised crops and livestock. In such ways as these, Tuskegee not only taught trades, crafts, and modern agricultural methods, but enabled students to earn the money for their tuition and other expenses.

|

| Top: Scene in the college library. Washington considered the library the center of Tuskegee's academic program. It was built with funds provided by industrialist Andrew Carnegie. Bottom: The story o the Negro's role in the development of the United States was an integral part of Tuskegee's courses in American history. (Library of Congress) |

As Tuskegee and its facilities grew, its courses in the building trades and engineering subjects were greatly expanded. Washington sought to give his industrial students "such a practical knowledge of some one industry, together with the spirit of industry, thrift, and economy, that they would be sure of knowing how to make a living after they had left us." At the same time, the desperate need for Negro teachers in the Southern rural districts was not forgotten. Tuskegee also offered students

such an education as would fit a large proportion of them to be teachers, and at the same time cause them to return to the plantation districts and show the people there how to put new energy and new ideas into farming as well as into the intellectual and moral and religious life of the people.

|

| Booker T. Washington in his office at Tuskegee. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

"I knew that, in a large degree, we were trying an experiment—that of testing whether or not it was possible for Negroes to build up and control the affairs of a large educational institution. I knew that if we failed it would injure the whole race."

Booker T. Washington

Tuskegee Institute survived its early years only through the unwavering perseverance of its founder and the dedication of those men and women who became his assistants. In the school's second month Washington was joined by Olivia A. Davidson, a graduate of Hampton and the Massachusetts State Normal School. This young Ohio-born Negro woman (whom Washington would later marry) combined a selfless nature with practical experience as a teacher and nurse. Besides teaching at Tuskegee, she served as Washington's general assistant and made several fund-raising trips in the North. Washington said, "No single individual did more toward laying the foundations of the Tuskegee Institute . . . than Olivia A. Davidson."

|

| Student teacher. Teacher training was popular among the girls. (Library of Congress) |

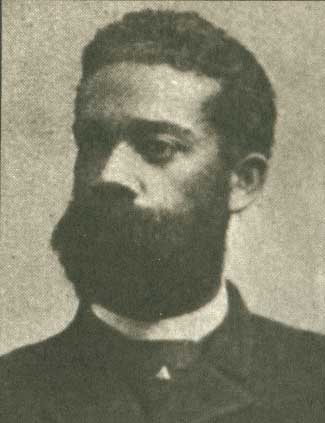

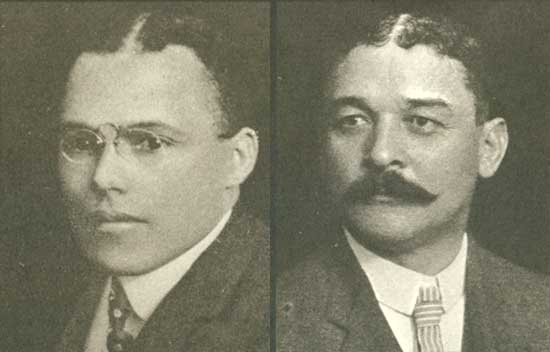

The men responsible for the school's operation during Washington's absences were Warren Logan and John H. Washington. Logan, a Hampton graduate, went to Tuskegee as a teacher in 1883 and was soon appointed treasurer. John Washington, Booker's half-brother, joined the staff in 1895. Also trained at Hampton, he became Tuskegee's superintendent of industries and supervised much of the school's educational activity.

|

| John Washington, Tuskegee's superintendent of industries. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

|

| Left: Emmett J. Scott, Booker T. Washington's secretary. Right: Warren Logan, teacher and the Institute's treasurer. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

In its second decade, Tuskegee acquired a teacher who would become as famous as its founder. The State of Alabama provided for an agricultural experiment station at Tuskegee in 1896 to be run in connection with the school's agricultural department. Dr. George Washington Carver was called from Iowa State College to lead these operations. He spent the rest of his life at Tuskegee, where he carried out his noted work in agricultural science.

|

| George Washington Carver (top) came to Tuskegee in 1896 to head the Institute's newly formed agricultural department. Under his tutelage, in the classroom, laboratory, and field, students learned the inter-relationsips between the soil, plants, and man. Most people know Carver today as the man who made the peanut and the sweet potato staples of the South's agricultural economy. (Top: George Washington Carver National Monument; Middle and Bottom: Library of Congress) |

The year after Dr. Carver's arrival, Washington engaged Emmett J. Scott as his personal secretary. Scott became Washington's most trusted confidant, serving as his contact with Tuskegee during the principal's long absences from the school in later years. Washington wrote of Scott that he

handles the bulk of my correspondence and keeps me in daily touch with the life of the school, and . . . also keeps me informed of whatever takes place in the South that concerns the race. I owe more to his tact, wisdom, and hard work than I can describe.

Two of the three women Washington would marry were members of the Tuskegee staff. The exception was Fannie Smith, a Malden girl who became his first wife in 1882. She died 2 years later, after bearing a daughter. Washington married his assistant, Olivia Davidson, in 1885; she gave birth to two sons before her death in 1889. His third marriage was to Margaret Murray, a Fisk University graduate, in 1893. Initially a teacher, she became Tuskegee's "lady principal" and was in charge of industries for girls. Margaret Murray Washington worked energetically in community and club affairs and accompanied her husband on many of his travels in later years.

Though he had a highly capable staff, Booker T. Washington was the great guiding force at Tuskegee—so much so that the man and the school were held to be virtually synonymous. His ability and determination in the face of the greatest obstacles were an inspiration to all those associated with him. At the same time, Washington's exacting, demanding manner made him difficult to work for. He drove himself and expected his assistants to keep pace.

|

| Tuskegee faculty about 1900. Washington expected each teacher to maintain certain standards and personally rebuked those who failed to measure up. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

Despite his full schedule, he paid great attention to detail, often riding about the campus at daybreak to inspect the facilities and teachers' homes. Any evidence of carelessness—trash lying about, a picket missing from a fence—was bound to provoke a reprimand. Everyone at Tuskegee was affected by Washington's puritannical insistence on personal cleanliness, typified by his "gospel of the toothbrush" which stipulated that no student could remain in the school unless he kept and used a toothbrush. Even in later years the principal himself often inspected the students, sending anyone with a missing button or soiled clothing to the dormitory to correct the deficiency.

Members of Washington's own family on the Tuskegee staff were shown no favoritism where official matters were concerned. The principal's memoranda to his wife Margaret were impersonally addressed to "Mrs. Washington." One such message, typical of those he sent, complained that "The yard of the Practice Cottage does not present a model appearance by any means. So far as I can see there is not a sign of a flower or anything like a flower or shrub in the yard." Perhaps it was this criticism that prompted a terse note from Margaret found in Washington's papers: "Umph! Umph!! Umph!!!"

Away from the office, Washington appears to have been an affectionate husband and father to his three children. He was often seen carrying his young sons about the campus, and his daughter was delighted to play the audience at her father's speech rehearsals. At home, too, Washington practiced his frequent preachments about the values of agriculture. He maintained his own kitchen garden, and took great interest in the progress of his pigs and other livestock.

"I never see a filthy yard that I do not want to clean it, a paling off of a fence that I do not want to put it on, an unpainted or unwhitewashed house that I do not want to paint or whitewash it, or a button off one's clothes, or a grease-spot on them or on a floor, that I do not want to call attention to it."

Booker T. Washington

Paralleling the story of Tuskegee's development and growth is the story of constant efforts to raise money. In the early years, the school was continually on the brink of insolvency.

Wrote Washington:

Perhaps no one who has not gone through the experience, month after month, of trying to erect buildings and provide equipment for a school when no one knew where the money was to come from, can properly appreciate the difficulties under which we laboured. During the first years at Tuskegee I recall that night after night I would roll and toss on my bed, without sleep, because of the anxiety and uncertainty which we were in regarding money.

Tuskegee's first income (other than the Alabama appropriation) was $250 borrowed from the treasurer of Hampton Institute for a down payment on the farm property. The loan and the balance of the $500 purchase price were paid by fund-raising concerts, suppers, and other local activities. During construction of the brick kiln, finances were so low that Washington pawned his watch for $15. In the following years, Washington traveled throughout the Nation to raise funds, making hundreds of visits and speeches to publicize the program and needs of Tuskegee Institute.

|

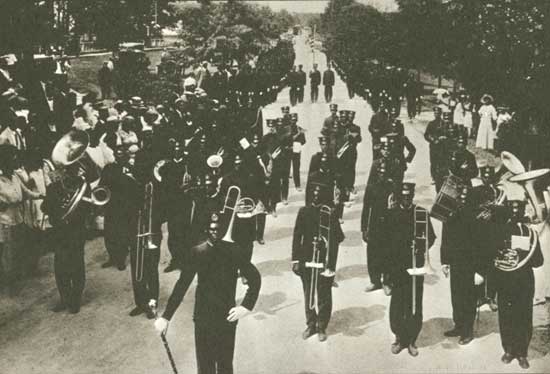

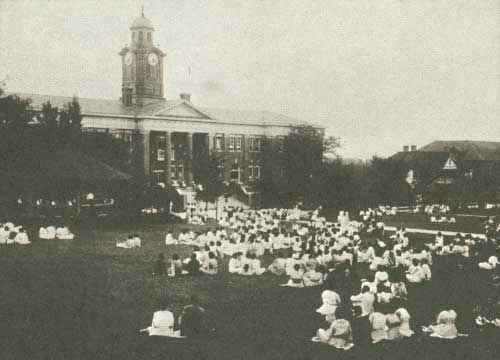

| Commencement day parade at Tuskegee, about 1913. Washington used the graduation exercises to inform visitors about Tuskegee programs. (Library of Congress) |

|

| Sunday afternoon band concerts on White Hall lawn were always well-attended by the students. The band also played every schoolday morning for inspection and drill. (Library of Congress) |

Booker T. Washington and his Tuskegee program came to have strong appeal for many white Americans sincerely concerned about the economic plight of the Negro. In an age that worshiped individual effort and self-help, this extraordinary former slave working to elevate his race from poverty was hailed by many as the answer to a great national problem. The appeal of Washington's educational philosophy and the force of his dynamic personality eventually won financial support from many of the era's foremost philanthropists. During Washington's lifetime, Tuskegee's more prominent benefactors included Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Julius Rosenwald, Collis P. Huntington, and the Phelps-Stokes family. Carnegie's gifts included a life income for Washington and his family.

"My experience has taught me that the surest way to success in education . . . is to stick close to the common and familiar things that concern the greater part of the people the greater part of the time."

Booker T. Washington

For Tuskegee Institute, the result was success beyond its founder's most optimistic expectations. At Washington's death, 34 years after his establishment of the school, the property included 2,345 acres and 107 buildings which, together with equipment, were worth more than $1-1/2 million. The faculty and staff numbered nearly 200, and the student body more than 1,500. The school had an endowment of $2 million. Tuskegee Institute was the world leader in agricultural and industrial education for the Negro.

|

| Each morning, mounted on his horse "Dexter," Washington made an inspection tour of the Institute's farms, truck gardens, dormitories, and shops. If he found any deficiency he expected it to be corrected immediately. (Library of Congress) |

"The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house."

Booker T. Washington, Atlanta Speech

|

| Washington's insistence on absolute cleanliness is reflected in the neat and orderly appearance of Alabama Hall, one of the first buildings erected on the campus and used as the girls' dormitory. (Library of Congress) |

By the mid-1890's Booker T. Washington and Tuskegee Institute were well known to educators and philanthropists, but not to the general public. Then Washington was asked to speak at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895. The speech he gave (reproduced in the appendix) catapulted him into national prominence-not only as an educator, but as leader and spokesman of his race.

The Atlanta speech, delivered before a large, racially mixed audience, contained Washington's basic philosophy of race relations for that unhappy period in American Negro history. At a time when blacks had been virtually eliminated from political life, Washington spoke disparagingly of Negro political activity during Reconstruction:

Ignorant and inexperienced, it is not strange that in the first years of our new life we began at the top instead of at the bottom; that a seat in Congress or the state legislature was more sought than real estate or industrial skill; that the political convention of stump speaking had more attractions than starting a dairy farm or truck garden.

|

| Top: Fannie Smith Washington; Middle: Olivia Davidson Washington; Bottom: Margaret Murray Washington. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

|

| Booker T. Washington and his family about 1899. Shown here with their father and stepmother Margaret Murray Washington are (left to right) Ernest Davidson Washington, born in 1889, Booker Taliaferro Washington, Jr., born in 1887, and Portia M. Washington, born in 1883. Washington's marriage to Margaret Murray was childless. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

He advised Southern Negroes to "cast down your bucket where you are" by cultivating friendly relations with white neighbors and concentrating on agriculture, industry, and the professions. "Our greatest danger," he said,

is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life; shall prosper in proportion as we learn to draw the line between the superficial and the substantial, the ornamental gewgaws of life and the useful.

For the time being, at least, Washington classed social integration with the "ornamental gewgaws":

The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing.

|

| Washington giving one of his sons a lesson in nature study. He wanted his children to learn, like his students at Tuskegee, something about the cultivation of flowers, shrubbery, vegetables, and other crops. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

Essentially, the speech was a bid for white support of Negro economic advancement, offering in exchange—at least for the present—black acceptance of political inactivity and social segregation. The "Atlanta compromise" is summarized in Washington's most remembered phrase: "In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress."

Response to the Atlanta speech—particularly white response—was highly enthusiastic. As the audience cheered wildly, Georgia's ex-Governor Rufus B. Bullock rushed across the platform to grasp Washington's hand. Newspapers throughout the country printed the speech in full and praised its author editorially. The Boston Transcript commented that the speech "seems to have dwarfed all the other proceedings and the Exposition itself. The sensation that it has caused in the press has never been equalled." The Atlanta Constitution called it "the most remarkable address ever delivered by a colored man in America . . . . The speech stamps Booker T. Washington as a wise counselor and a safe leader."

|

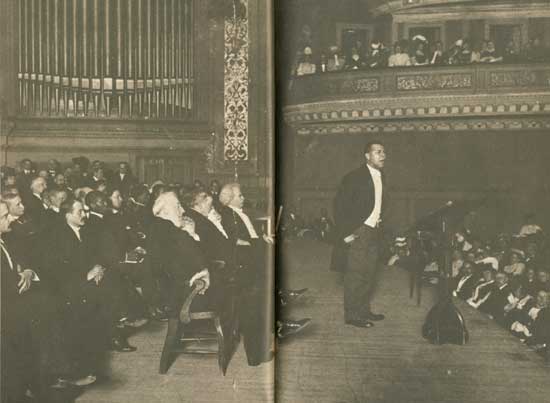

| Much of Washington's effectiveness as a leader was due to his abilities as a public speaker. Whether exhorting a crowd in Louisiana (top) or addressing a gathering of socialites at Carnegie Hall (bottom), his speeches were usually extemporaneous, informal, conversational, and filled with personal experiences and observations. He consciously avoided "the language of books or the statements in quotations from the authors of books." (Top: Library of Congress; Bottom: Underwood and Underwood) |

After the speech, Washington became an object of nationwide attention and honor. Frederick Douglass, the great 19th-century Negro leader, had died only 7 months earlier, and Washington was widely acclaimed as his successor. Harvard awarded him an honorary M.A. degree in 1896, the first granted any Negro by that university. Dartmouth followed with an honorary doctorate. President William McKinley visited Tuskegee in 1898. A year later white friends sent Washington and his wife on a European tour, during which they had tea with Queen Victoria. Deluged with speech offers, Washington—a brilliant orator—spent an increasing portion of his time on the lecture circuit. He became friendly with the Nation's leading citizens in the business and literary worlds and was accepted in white society to a degree never before achieved by a Negro.

In response to numerous requests for his autobiography, Washington wrote Up From Slavery. Published in 1900, the book was an immediate best seller. It related the dramatic story of Washington's personal rise to prominence, and gave particular attention to his educational philosophy. Royalties and contributions from readers were a major source of income for Tuskegee. (Andrew Carnegie, its greatest single benefactor, became interested in the school only after reading Up From Slavery.) Washington also wrote or contributed to 12 other books and countless articles on the life of the Negro.

"Friction between the races will pass away as the black man, by reason of his skill, intelligence, and character, can produce something that the white man wants or respects in the commercial world."

Booker T. Washington

In his books, articles, and speeches, Washington continually stressed the educational and social views expounded in the Atlanta speech and Up From Slavery. His fundamental thesis was that economic progress held the key to Negro advancement in all other areas. With material betterment, the race would rise naturally, without "artificial forcing," in the political and social spheres. "The black man that has mortgages on a dozen men's houses will have no trouble in voting and having his vote counted," he declared. "No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized."

Washington was a pragmatist, not given to speaking out for lost causes. When Louisiana was preparing to disfranchise Negroes, he made a strong public appeal against such discrimination. His appeal failed, and thereafter Washington usually accommodated his pronouncements to Southern realities. He said in Up From Slavery,

I believe it is the duty of the Negro . . . to deport himself modestly in regard to political claims, depending upon the slow but sure influences that proceed from the possession of property, intelligence, and high character for the full recognition of his political rights.

He rationalized that propertied Negroes often exerted political influence in matters concerning their race even without going through "the form of casting the ballot."

Despite the deterioration of the Negro's position in American society, optimism ran through nearly all of Washington's utterances. "On the whole," he stated, "the Negro has been and is moving forward everywhere and in every direction." He played down the ill effects of discrimination, and stressed the benefits to be derived from meeting the challenges of adversity. After a second trip to Europe in 1910, he wrote The Man Farthest Down, portraying American Negroes as better off than the European peasantry. Washington's optimistic stance was intended less to reflect reality than to encourage "positive thinking":

There is no hope for any man or woman, whatever his color, who is pessimistic, who is continually whining and crying about his condition. There is hope for any people, however handicapped by difficulties, that makes up its mind that it will succeed . . . .

The key ingredients in Washington's public pronouncements—materialism, pragmatism, optimism—were among the dominant values of the age in which he worked. His skill in applying these values to the problems of Negro education and race relations was largely responsible for his success in gaining support from the contemporary Establishment. He told white society what it wanted to hear, in terms it could understand. In return, he was hailed by that society as "reasonable," "safe," and "constructive." Booker T. Washington was thoroughly in tune with the majority sentiment of his time.

"I do not like politics, and yet, in recent years, I have had some experience in political matters."

Booker T. Washington, 1911

While Washington the spokesman was a figure of national prominence, Washington the politician was far less known. He never held public office and expressed aversion to political dealings. Yet during the Roosevelt and Taft administrations, he played an important role as unofficial adviser on racial matters and Negro political appointments throughout the Nation.

Theodore Roosevelt's close relationship with Washington occasioned, in the eyes of many Southern whites, a rare instance in which the Negro leader stepped "out of his place." After learning that Washington had dined at the White House with the Roosevelt family, Southern newspapers and politicians loudly berated both him and the President for ignoring the color line. "The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the South before they learn their place again," ranted Senator Ben Tillman. Less concern was expressed over the more significant fact that Washington had been conferring with the President on political matters.

|

| Theodore Roosevelt (shown here during his 1905 visit to Tuskegee) relied heavily upon Washington's advice when making Negro appointments. Washington's influence with the Roosevelt administration was much criticized, as the cartoon (at bottom) indicates. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

Washington worked quietly for William Howard Taft's election in 1908 and continued to wield some influence during his administration. A letter from Washington to Taft defines his relationship with both Presidents:

It was very kind of you to send me word that you wished to consult with me fully and freely on all racial matters during your administration. I assure you I shall be glad to place myself at your service at all times. . . . The greatest satisfaction that has come to me during the administration of President Roosevelt is the fact that perhaps I have been of some service to him in helping to raise the standard of the colored people, in helping him to see that men holding office under him were men of character and ability. . . .

Washington's political skills also served him in private affairs. Paralleling his role as Presidential adviser on public appointments was his role as adviser to philanthropists aiding Negro causes. As noted earlier, he was remarkably successful in securing funds for Tuskegee from the foremost industrialists and financiers of the day. At the same time, he obtained their support for other agencies working on behalf of Negro education in the South.

|

| Among Tuskegee's most influential backers were merchant and philanthopist Robert C. Ogden, Secretary of War (later President) William Howard Taft, and industrialist Andrew Carnegie. (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

Washington's commanding influence in the white world concerning Negro affairs led to what W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, a black critic, called the "Tuskegee Machine":

It arose first quite naturally. Not only did presidents of the United States consult Booker Washington, but governors and congressmen; philanthropists conferred with him, scholars wrote to him. Tuskegee became a vast information bureau and center of advice. . . . After a time almost no Negro institution could collect funds without the recommendation or acquiescence of Mr. Washington. Few political appointments [of Negroes] were made anywhere in the United States without his consent. Even the careers of rising young colored men were very often determined by his advice and certainly his opposition was fatal.

Convinced that Negro progress necessitated the good will of the white South, Washington seldom dropped his accommodating, conciliatory tone. Publicly, he often minimized the evils of segregation and discrimination. Privately, and unknown to his critics, he was deeply involved in fighting many of the racial injustices then sweeping the South.

"My check book will show that I have spent at least four thousand dollars in cash, out of my own pocket, during [1903-1904], in advancing the rights of the black man."

Booker T. Washington to J. W. E. Bowen, 1904

Washington used his personal funds and influence to combat disfranchisement in a number of States, often working through legal test cases. While publicly accepting railroad segregation, he acted behind the scenes to halt its spread. He was involved in court cases opposing Negro exclusion from juries, helping with money and personal attention until their successful conclusion in the Supreme Court. For more than 2 years he worked on a case against Negro peonage, or forced labor, obtaining the services of prominent Alabama lawyers. He fought the Republican "Lily-White" movement which repudiated that party's traditional support for the Negro. To preserve his "safe" public image, Washington often masked his role in such activities with the greatest secrecy: during the battle against disfranchisement in Louisiana, his secretary and lawyer corresponded using pseudonyms and code.

August Meier, a modern historian researching Washington's private correspondence, helped bring to light this "militant" side of Washington—a side virtually unknown to his contemporaries:

. . . in spite of his placatory tone and his outward emphasis upon economic development as the solution to the race problem, Washington was surreptitiously engaged in undermining the American race system by a direct attack upon disfranchisement and segregation; . . . in spite of his strictures against political activity, he was a powerful politician in his own right. The picture that emerges from Washington's own correspondence is distinctly at variance with the ingratiating mask he presented to the world.

Washington concluded early that if his educational efforts were to prosper, he would need the support of three divergent groups: Northern philanthropists, Southern whites of the "best class," and Negroes. All of his public pronouncements were carefully composed for their effect on these factions. Then as now, however, it was impossible for anyone involved with race relations to please all of the people all of the time. Washington was highly popular with Northern philanthropists. He seldom lost the "best class" of Southern whites—the aftermath of the White House dinner was a rare exception. Significantly, members of his own race were his most outspoken critics.

Negro dissent from Washington's policies dated from the Atlanta speech. As Washington observed, some blacks "seemed to feel that I had been too liberal in my remarks toward the Southern whites, and that I had not spoken out strongly enough for what they termed the 'rights' of the race." His most vocal opposition came from a small group of Negro intellectuals, who in the following years criticized both his educational and social views.

". . . there is among educated and thoughtful colored men in all parts of the land a feeling of deep regret, sorrow, and apprehension at the wide currency and ascendancy which some of Mr. Washington's theories have gained."

W. E. B. Du Bois, 1903

Most bitterly critical was William Monroe Trotter of the Boston Guardian. Trotter denied that Washington was a true leader of the race, claiming that he had been elevated to that position by whites alone. He regarded Washington's concentration on manual training for blacks and his accommodating approach to the loss of civil rights as traitorous and charged that he was being used by whites to "master the Colored Race."

|

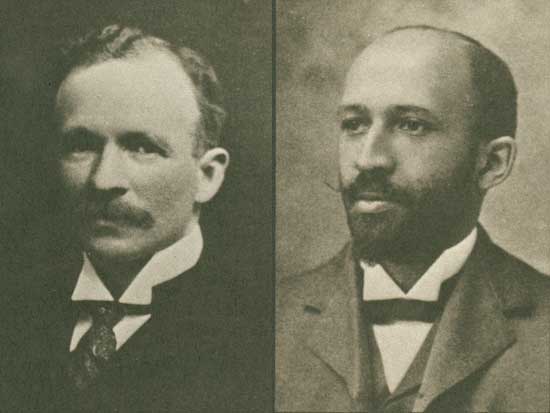

| Charles W. Chestnutt (left) and W. E. B. Du Bois (right). (Booker T. Washington National Monument) |

Author Charles W. Chesnutt, in a review of Washington's book The Future of the American Negro, approved his goal of gaining white good will and, despite disagreement with his materialistic emphasis, generally supported his educational work. But Chesnutt strongly opposed Washington's apparent acceptance of inequality:

He has declared himself in favor of a restricted suffrage, which at present means, for his own people, nothing less than complete loss of representation . . .; and he has advised them to go slow in seeking to enforce their civil and political rights, which, in effect, means silent submission to injustice. Southern white men may applaud this advice as wise, because it fits in with their purposes; but Senator McEnery of Louisiana . . . voices the Southern white opinion of such acquiescence when he says: "What other race would have submitted so many years to slavery without complaint? What other race would have submitted so quietly to disfranchisement? These facts stamp his (the Negro's) inferiority to the white race." . . . To try to read any good thing into these fraudulent Southern constitutions, or to accept them as an accomplished fact, is to condone a crime against one's race. Those who commit crime should bear the odium. It is not a pleasing spectacle to see the robbed applaud the robber. Silence were better.

Washington's most influential critic was W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, the first Negro to receive a Ph.D. degree from Harvard. A professor at Atlanta University, Du Bois advocated higher education for a "talented tenth" of Negroes who would serve as leaders. He felt that by overemphasizing industrial training and yielding to racism, Washington was in effect accepting the myth of black inferiority. Wrote Du Bois:

In other periods of intensified prejudice all the Negro's tendency to self-assertion has been called forth; at this period a policy of submission is advocated. In the history of nearly all other races and peoples the doctrine preached at such crises has been that manly self-respect is worth more than lands and houses, and that a people who voluntarily surrender such respect, or cease striving for it, are not worth civilizing.

Du Bois noted that Washington's ascendancy was accompanied by black disfranchisement, loss of civil rights, and withdrawal of aid from Negro institutions of higher learning. He blamed Washington's policies for encouraging these developments, and asked,

Is it possible . . . that nine millions of men can make effective progress in economic lines if they are deprived of political rights, made a servile caste, and allowed only the most meagre chance for developing their exceptional men?

Many criticisms of Washington centered around his exercise of power. Widely acclaimed as the foremost Negro leader, he came to hold a virtual monopoly over "acceptable" racial policies and practices. The dominance of the "Tuskegee Machine" made it extremely difficult for individuals or institutions with differing ideas to prosper. Most critics did not deny the need for training of the type offered at Tuskegee, but they felt it should not rule the day at the expense of liberal education. Especially resented was Washington's widespread control of the Negro press, through clandestine ownership and subsidy, in an attempt to maintain a united black front in his favor. Du Bois pointed up the extent of this monopolistic influence: "Things came to such a pass that when any Negro complained or advocated a course of action, he was silenced with the remark that Mr. Washington did not agree with this."

Washington's opponents generally sympathized with his goal of winning white support. But they felt that he wrongly attempted to curry favor by telling his white audiences what they wanted to hear rather than what they needed to hear. Although Washington was combating discrimination to a far greater extent than his critics realized, so he felt obliged to keep these activities secret so he could maintain an amenable public image. For many Negroes the image was that of "Uncle Tom."

|

| The leaders of the Niagara Movement, forerunner of the NAACP, during their 1905 meeting near Niagara Falls. They oppposed Washington's conciliatory, compromising attitudes and demanded immediate political, civil, and social rights for the Negro. W. E. B. Du Bois is second from the right in the middle row. (Crown Publishers, Inc., A Pictorial History of the Negro in America, by Langston Hughes and Milton Meitzer) |

With the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1910, those favoring open agitation on behalf of political and civil rights organized for action. This biracial group included such prominent persons as Oswald Garrison Villard, a white editor and philanthropist who had supported Tuskegee; Ida B. Wells Barnett, an outspoken black critic of Washington; and Du Bois, who became editor of The Crisis, the organization's publication. The association devoted much effort to publicity and legal action and won a variety of important court victories.

Washington approved of the NAACP's objectives and much of its work but he feared that its militant tone would alienate many whites. Its intellectual leaders, he said, did not understand the practical problems of the great majority of Southern Negroes. No doubt he also saw the NAACP as a threat to his own preeminence. But, perhaps partly as a result of the new organization's growing influence, Washington in his later years became somewhat more outspoken on behalf of Negro rights.

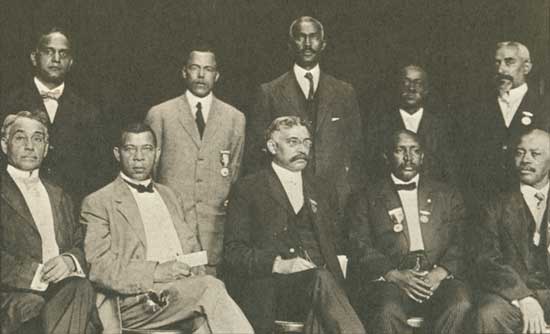

Washington's personal success never caused him to relax his vigorous efforts on behalf of his school and his race. Even after it was discovered that he had diabetes, he refused to slacken his pace. His last year's schedule was typical. In the spring of 1915 he initiated a major fund-raising campaign. That summer he spoke in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New York, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Ohio, and Nova Scotia. Between these engagements he attended trustee meetings in New York, returned to Tuskegee for a series of summer school lectures, and presided over the 15th anniversary meeting of the National Negro Business League, an organization he had founded to help black commercial enterprises.

|

| Washington's daily mail amounted to between 125 and 150 lettes; they were answered with judgment and tact. (Library of Congress) |

Noting that Washington's health was suffering, Scott and others persuaded him to take 2 weeks off in September for a fishing trip. But the next month he was back on his schedule, speaking before a church council in New Haven, Conn. It was to be his last public appearance. He collapsed in New York and was taken to a hospital. Told he was dying, Washington insisted upon returning to Tuskegee: "I was born in the South, I have lived and labored in the South, and I expect to die and be buried in the South." His determination never failing him, he survived the journey to Tuskegee by a few hours. Death came on the morning of November 14, 1915. He was buried 3 days later on the campus of the institution he founded.

"More and more we must come to think not in terms of race or color or of language or religion or of political boundaries, but in terms of humanity."

Booker T. Washington

Even those who disagreed with Booker T. Washington could not deny the greatness of the man nor the fact that his death was a loss to his race and his country. Du Bois called him

the greatest Negro leader since Frederick Douglass and the most distinguished man, white or black, who has come out of the South since the Civil War. Of the good that he accomplished there can be no doubt; he directed the attention of the Negro race in America to the pressing necessity of economic development; he emphasized technical education and he did much to pave the way for an understanding between the white and darker races.

|

| Washington founder and president of the National Negro Business League, sits with members of the executive committee during one of the League's annual meetings. (Library of Congress) |

Theodore Roosevelt, one of Washington's greatest admirers, expressed the sentiment of much of the Nation:

It is not hyperbole to say that Booker T. Washington was a great American. For twenty years before his death he had been the most useful, as well as the most distinguished, member of his race in the world, and one of the most useful, as well as one of the most distinguished, of American citizens of any race.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

bowa/mackintosh/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Feb-2009