|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

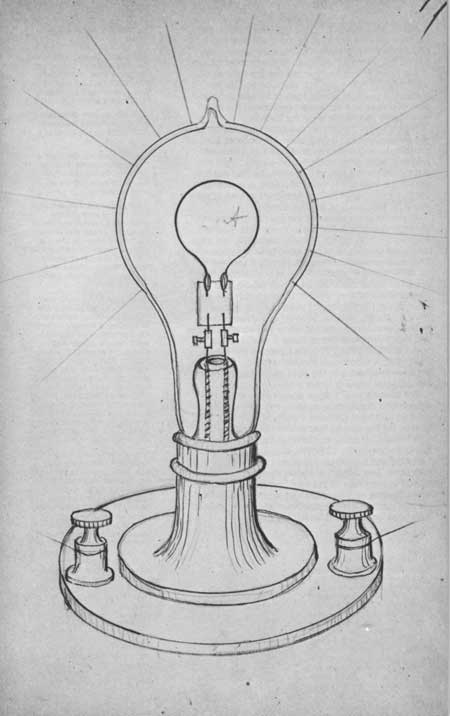

The Search For The Right Filament

Whenever we made an incandescent lamp for our experiments, we had to go through the following processes:

First, the raw material for the filament had to be chosen. ... Edison tried everything he could lay his hands on, and when some material exhibited good qualities, he noted in his book "T.A."—Try Again. Among the other materials, he once tried common cotton thread from a spool. It was not satisfactory; yet he perceived something that prompted him to mark it for later trial. The second test was made with a special thread from the Clark Thread Mills in Newark, where Charles Batchelor and Will Carman had at one time worked.

The second step was the preparation of the raw filament. This work Edison always did himself. . . .

Third, each filament had to be carbonized, a process he attended to personally on the experimental lamps. Only after he had mastered the art thoroughly and desired carbons in quantity did he instruct "Basic" Lawson [Lawson became chief carbonizer at the first commercial lamp factory] and some of the new men in the art and assign them to the job.

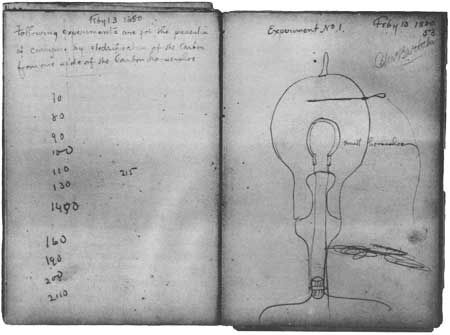

The drawing of the incandescent lamp appears in a Menlo Park notebook and is dated September 20, 1879. |

Fourth, [John] Kruesi supplied the copper wires, on the end of which short pieces of platinum had been twisted.

Fifth, [Ludwig] Boehm blew the glass stem, inserting in it the copper-platinum wires.

Sixth, after being carbonized the filament was placed on the glass stem of the bulb. This delicate task was always performed by "Batch" in Edison's presence.

Seventh Boehm inclosed the stem with its filament within the fragile shell of a glass bulb.

Eighth, I placed the bulb on the vacuum pump and began evacuating the air. Martin Force relieved me on rare occasions.

Ninth, after the vacuum was obtained, it was always Edison who drove out the occluded gases and manipulated the lamp. When the difficult research period was past and the development period came, Edison often entrusted this whole process to me.

Tenth, when the lamp was finished, it was given a life test, the process consisting in sending a current through the filament at an approximate candle power and noting the number of hours it lived. The life test before November, 1879, was generally conducted in conjunction with other work. Experimental lamps would last from a few minutes to many hours, their value not be coming known until they had finished the test. A lamp was born when it died.

This outline does not convey a fair idea of the tedious, back-breaking and heart-breaking delays experienced as we went through the various processes. "Batch" sometimes spent two or three days getting a filament on the stem, only to have it break; whereupon the work had to be done over. And an accident was no wonder; for a carbon filament thin as a hair had to be connected with a length of wire equally thin! The hours spent in waiting while the carbonized filaments were in the furnace can hardly be estimated.

Notebook pages for February 13, 1880, show experiments with what became known as Edison-Effect lamps, a forerunner of the radio tube. In contrast to the complexities of electronics, the electric lamp patent application seems quite simple. |

So with the process of driving out occluded gases, It had to be performed precisely, step by step, with at first but little current for short periods and then a gradual increase during six or eight hours, when finally the filament could stand the whole heat of the electricity without disintegrating.

I have but to close my eyes to see once more the picture of our patient, painstaking, keenly observing chief carrying on his endless experiments, and at the same time educating and directing us. We never thought him wrong, whatever leading scientists said. Our quest never seemed vain or foolish.

I see him tap carefully on the bulb with sensitive fingers as he watches for spots or irregularities in the carbon. If its condition appears good he proceeds even more carefully, If it does not, he is not greatly worried. I have never seen a man so cool when great stakes were at odds.

After the lamp, good or bad, has finished its test he breaks it open and takes it to the microscope to study the filaments, seeking the reason for the failure of the slender black threadlike substance.

Francis Jehl, Menlo Park Reminiscences, 1936

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |