|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

After The Lamp, He Created A Whole Electric

System

I had a great idea of the sale of electric power to large factories, etc., of the electric lighting system; and I got all the insurance maps in New York City, and located all the hoists, printing presses, and other places where they used power. I put all these on the maps, and allowed for the necessary copper in the mains to carry current to them when I put the mains down; so that when these places took current from the station I would be prepared to furnish it because I had allowed for it in the wiring. There were, I remember, 554 hoists in that district. In some places, a horse would be taken upstairs to run a hoist, and would be kept there until he died.

Thomas A. Edison, as quoted in Forty Years of Edison Service, 1922

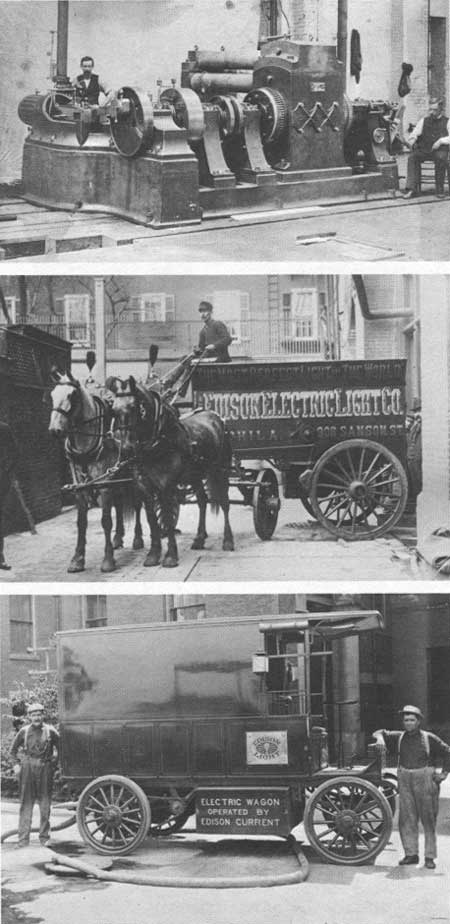

The electric power industry called for the development of all kinds of equipment and created many new business opportunities and jobs, such as tending the Edison Jumbo Steam Dynamo at Edison Machine Works on Goerck Street in New York City. Horse-drawn wagons delivered the coal to run the dynamos in Philadelphia, but soon electric-powered vehicles were being used by Edison employees. |

Some of Edison's first electric power customers in New York were a bit skeptical about the accuracy of his meters that measured the electricity used. One such skeptic was one of America's leading financiers.

Mr. John Pierpont Morgan . . . wasn't at all sure about the inerrancy of that queer "wet measure"; so cards were printed and hung on each fixture in the Morgan offices in Wall Street. Each card noted the number of lamps on the fixture and the time at which they were turned on and off each day. The test was for a month, at the end of which the lamp hours were added up and figured out on an hourly basis. "Kilowatts" and "kilowatt hours" were a refinement quite unknown then to the art, the customers or the dictionaries. The total reached was then compared with the bill rendered by the [Edison] Company. One likes to think of the great Morgan, dealing in millions, thus putting a new meter on test, to check it up. The results of the first month revealed an apparent overcharge. Mr. Morgan chuckled. Edison took it quite serenely and suggested giving the little beggar another chance. Once more the same thing happened, and the chuckle became a broad grin . . . . Then Edison went "sleuthing" himself. He inspected the Drexel, Morgan offices carefully—the wires and fixtures critically—looked over the hourly records, and then asked who did the chores after dark. He was told that the janitor—really a very excellent chap—cleaned up the place. The janitor was sent for and when inquiry was made as to the light he used in mopping up the floors, pointed to a central fixture carrying ten lamps. He had made no record of its nightly use—hadn't been asked to. Told to make note every night of his use of it during a month, he did so; and when the next bill came in, it was found that the meter had registered within a very small fraction the actual lamphour consumption as computed from the cards. The joke was on Mr. Morgan, who became a highly enthusiastic advocate of a meter that could so much more satisfactorily stand interrogation than others who came after the financier's money.

Thomas C. Martin, Forty Years of Edison Service, 1922

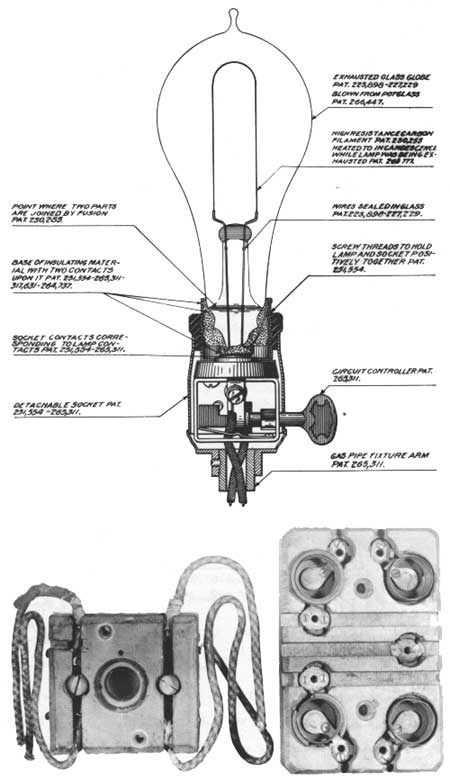

The incandescent lamp sketch shows some of Edison's electric light patents. The socket, left, and the fuse block were made of wood. |

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |