|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

From The Man Who Brought You The Movies

In recent years Edison's role as a cinematographic pioneer has been criticized by some scholars. Here is a more traditional view of Edison's contributions:

In 1896, on top of a building in New York City, May Irwin and John C. Rice embrace in "The Kiss From Widow Jones." Their prolonged cinema kiss drew large crowds—and a few calls for censorship. |

The most that could be said of the condition of the art when Edison entered the field was that it had been recognized that if a series of instantaneous photographs of a moving object could be secured at an enormously high rate—many times per second—they might be passed before the eye either directly or by projection upon a screen, and thereby result in a reproduction of the movements. Two very serious difficulties lay in the way of actual accomplishment, however—first, the production of a sensitive surface in such form and weight as to be capable of being successively brought into position and exposed, at the necessarily high rate; and, second, the production of a camera capable of so taking the pictures. . . . In the earliest experiments attempts were made to secure the photographs, reduced microscopically, arranged spirally on a cylinder about the size of a phonograph record, and coated with a highly sensitized surface, the cylinder being given an intermittent movement, so as to be at rest during each exposure. Reproductions were obtained in the same way, positive prints being observed through a magnifying glass. . . . During the experimental period and up to the early part of 1889, the kodak film was being slowly developed by the Eastman Kodak Company. Edison perceived in this product the solution of the problem on which he had been working, because the film presented a very light body of tough material on which relatively large photographs could be taken at rapid intervals. The surface, however, was not at first sufficiently sensitive to admit of sharply defined pictures being secured at the necessarily high rates. . . . Much credit is due the Eastman experts—stimulated and encouraged by Edison, but independently of him—for the production at last of a highly sensitized, fine-grained emulsion presenting the highly sensitized surface that Edison sought.

Having at last obtained apparently the proper material upon which to secure the photographs, the problem then remained to devise an apparatus by means of which from twenty to forty pictures per second could be taken; the film being stationary during the exposure and, upon the closing of the shutter, being moved to present a fresh surface. In connection with this problem it is interesting to note that this question of high speed was apparently regarded by all Edison's predecessors as the crucial point. . . .

After the accomplishment of the fact, it would seem to be the obvious thing to use a single lens and move the sensitized film with respect to it, intermittently bringing the surface to rest, then exposing it, then cutting off the light and moving the surface to a fresh position; but who, other than Edison, would assume that such a device could be made to repeat these movements over and over again at the rate of twenty to forty per second? . . . Edison's solution of the problem involved the production of a kodak in which from twenty to forty pictures should be taken in each second, and with such fineness of adjustment that each should exactly coincide with its predecessors even when subjected to the test of enlargement by projection. This . . . was finally accomplished, and in the summer of 1889 the first modern motion-picture camera was made. More than this, the mechanism for operating the film was so constructed that the movement of the film took place in one-tenth of the time required for the exposure, giving the film an opportunity to come to rest prior to the opening of the shutter.

Frank L. Dyer and Thomas C. Martin, Edison: His Life end Inventions, 1910

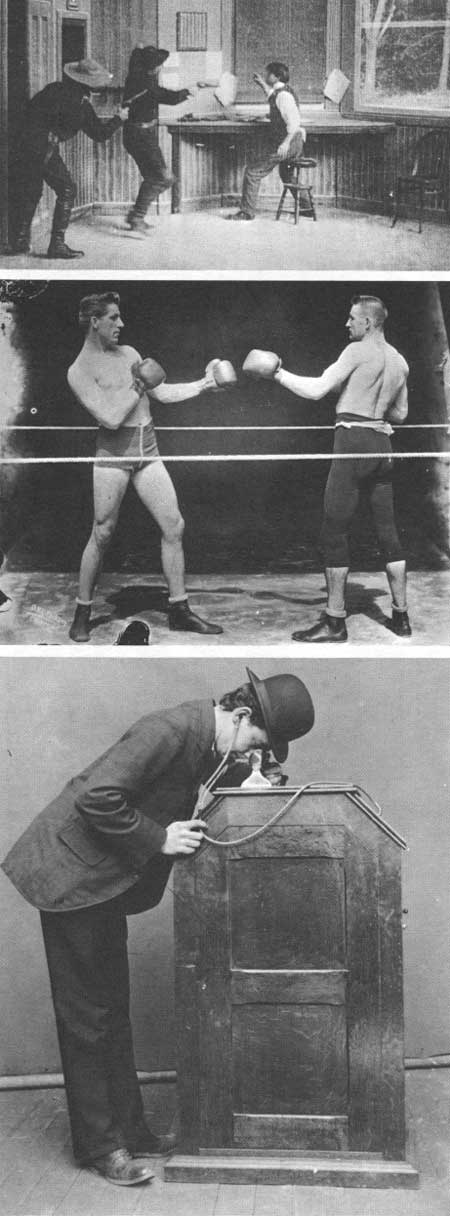

Edison's "The Great Train Robbery," filmed in 1903, was one of the first motion pictures with a story line and was made to be projected in theaters. Long lines of people waiting to see such shows as a fight between Gentleman Jim Corbett and Pete Courtenay in the earlier peephole Kinetoscopes sparked demands for mass shows. The staged fight, incidentally, took place in the Black Maria. |

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |