|

Beehives of Invention Edison and His Laboratories |

|

The Phonograph Became An Industry

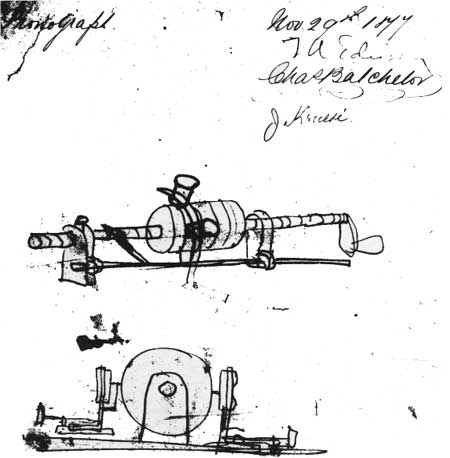

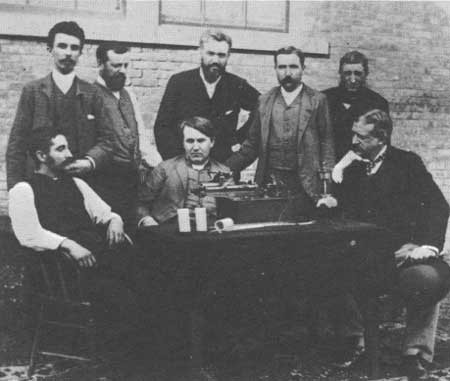

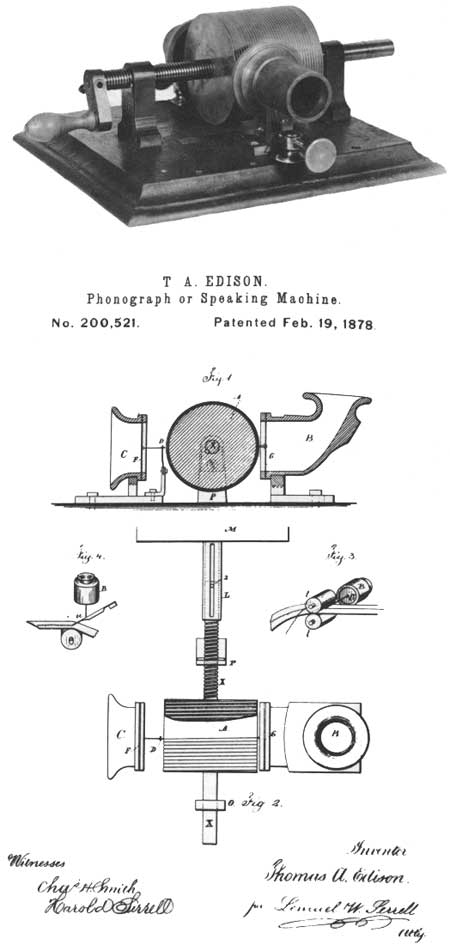

By supposedly following Edison's sketch (top), John Kruesi built the first tinfoil phonograph, top right, in 1877. Though improved by Edison in 1888 and thereafter, the phonograph essentially remained the simple machine delineated in the original patent drawings. Gathered around the 1888 model after a 72-hour stint of modifications (bottom), are, seated from left, Fred Ott, Edison, Col. George E. Gouraud; standing, from left, W. K. L. Dickson, Charles Batchelor, A. Theodore E. Wangemann, John Ott, and Charles Brown. |

The original phonograph, as invented by Edison, remained in its crude and immature state for almost ten years—still the object of philosophical interest, and as a convenient text book illustration of the effect of sound vibration. . . . In 1887 his time was comparatively free, and the phonograph was then taken up with renewed energy, and the effort made to overcome its mechanical defects and to furnish a commercial instrument, so that its early promise might be realized. The important changes made from that time up to 1890 converted the phonograph from a scientific toy into a successful industrial apparatus. The idea of forming the record on tinfoil had been early abandoned, and in its stead was substituted a cylinder of wax-like material, in which the record was cut by a minute chisel-like gouging tool. Such a record or phonogram, as it was then called, could be removed from the machine or replaced at any time, many reproductions could be obtained without wearing out the record, and whenever desired the record could be shaved off by a turning-tool so as to present a fresh surface on which a new record could be formed, something like an ancient palimpsest. A wax cylinder having walls less than one-quarter of an inch in thickness could be used for receiving a large number of records, since the maximum depth of the record groove is hardly ever greater than one one-thousandth of an inch. Later on, and as the crowning achievement in the phonograph field, from a commercial point of view, came the duplication of records to the extent of many thousands from a single "master." . . . Another improvement . . . was making the recording and reproducing styluses of sapphire, an extremely hard, non-oxidizable jewel, so that those tiny instruments would always retain their true form and effectively resist wear. . . . After a considerable period of strenuous activity in the eighties, the phonograph and its wax records were developed to a sufficient degree of perfection to warrant him in making arrangements for their manufacture and commercial introduction. At this time the surroundings of the Orange laboratory were distinctly rural in character. Immediately adjacent to the main building and the four smaller structures, constituting the laboratory plant, were grass meadows that stretched away for some considerable distance in all directions, and at its back door, so to speak, ducks paddled around and quacked in a pond undisturbed. Being now ready for manufacturing, but requiring more facilities, Edison increased his real-estate holdings by purchasing a large tract of land lying contiguous to what he already owned. At one end of the newly acquired land two unpretentious brick structures were erected, equipped with first-class machinery, and put into commission as shops for manufacturing phonographs and their record blanks, while the capacious hall forming the third story of the laboratory, over the library, was fitted up and used as a music-room where records were made. Thus the modern Edison phonograph made its debut in 1888, in what was then called the 'aim proved' form . . . viz., the spring or electric motor-driven machine with the cylindrical wax record—in fact, the regulation Edison phonograph.

Frank L. Dyer and Thymes C. Martin. Edison: His Life and Inventions, 1910

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Thurs., May 19 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |