|

YELLOWSTONE

"The place where Hell bubbled up" A History of the First National Park |

|

THE IDEA OF YELLOWSTONE

One morning in May 1834, in the northwest corner of Wyoming three men waited anxiously for the end of a night of strange noises and curious smells. Warren Ferris, a clerk for the American Fur Company, had ventured into the upper Yellowstone country with two Indian companions to find out for himself the truth about the wild tales trappers told about the region. It was a place, they said, of hot springs, water volcanoes, noxious gases, and terrifying vibrations. The water volcanoes especially interested him, and now, as dawn broke over the Upper Geyser Basin, Ferris looked out on an unforgettable scene:

Clouds of vapor seemed like a dense fog to overhang the springs, from which frequent reports or explosions of different loudness, constantly assailed our ears. I immediately proceeded to inspect them, and might have exclaimed with the Queen of Sheba, when their full reality of dimensions and novelty burst upon my view, "The half was not told me." From the surface of a rocky plain or table, burst forth columns of water, of various dimensions, projected high in the air, accompanied by loud explosions, and sulphurous vapors. . . . The largest of these wonderful fountains, projects a column of boiling water several feet in diameter, to the height of more than one hundred and fifty feet accompanied with a tremendous noise. . . . I ventured near enough to put my hand into the water of its basin, but withdrew it instantly, for the heat of the water in this immense cauldron, was altogether too great for comfort, and the agitation of the water . . . and the hollow unearthly rumbling under the rock on which I stood, so ill accorded with my notions of personal safety, that I retreated back precipitately to a respectful distance.

Ferris later recalled that his companions thought it unwise to trifle with the supernatural:

The Indians who were with me, were quite appalled, and could not by any means be induced to approach them. They seemed astonished at my presumption in advancing up to the large one, and when I safely returned, congratulated me on my "narrow escape" . . . One of them remarked that hell, of which he had heard from the whites, must be in that vicinity.

Ferris and his friends quickly concluded their excursion and went back to earning a living in the fur trade. They had not been the first visitors to this land of geysers. But they were the first who came as "tourists," having no purpose other than to see the country.

|

| The Lower Falls of the Yellowstone Rive, photographer by Jackson. |

|

| Members of the Hayden party, which explored the Yellowstone Region in 1871 and 1872, observe the eruption of Old Faithful. At left is Jackson's record of Tower Creek. |

|

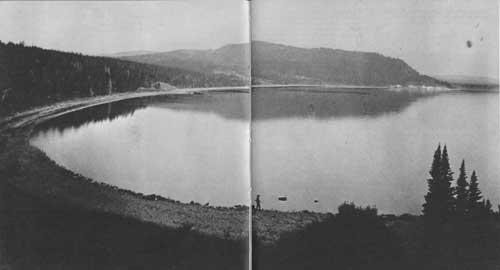

| A hunter with the Hayden party looks out over the quiet waters of Mary Bay, on the east side of Yellowstone Lake. Photographed by Jackson in 1871. |

|

| Jackson considered Castle Geyser, in the Upper Geyser Basin, one of the most spectacular thermal featues in Yellowstone. |

It was the awesome evidence of this land's great volcanic past that drew Ferris and his comrades, and others after them, into an uncharted wilderness. For whatever the other attractions of this region—and there are many—man has reacted most to this spectacle of a great dialetic of nature, this apparent duel between the hot earth and the waters that continually attempt to invade it.

Seething mud pots, hot pools of delicate beauty, hissing vents, periodic earthquakes, and sudden, frightening geysers are foreign to our ordinary experience. But in this region a wonderful variety of such features, seeming to speak of powers beyond human comprehension, confronts visitors at every turn. So it is easy to understand why many observers have speculated, along with the companions of Warren Ferris, that this may indeed be near the dark region of the white man's religion.

Yet this Biblical metaphor, which came so naturally to men of the 19th century, fails to evoke the full sense of Yellowstone. Lt Gustavus C. Doane, who explored the country on the celebrated 1870 expedition, thought that "No figure of imagination, no description of enchantment, can equal in imagery the vista of these great mountains." There is the stately lodgepole forest, the ranging wildlife, the fantastic geysers, and the great lake, and there is the mighty torrent of the Yellowstone River, the spectacular waterfalls, and the rugged, many-hued chasm from which the river and ultimately the region took its name. And beyond all this, there is Yellowstone the symbol. The notion that a wilderness should be set aside and perpetuated for the benefit of all the people—a revolutionary idea in 1872—has flowered beyond the wildest dreams of those who conceived it.

This is the story, in broadest outline, of the people who have visited this remarkable country, of their influence upon it, and of Yellowstone's influence upon them. It begins long ago, as all such stories must on the American continent, with the red man.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

clary/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2009