The Mountains of Glacier

Lying astride the Continental Divide in the Northern Rockies, Glacier is

above all else a mountain park. The special beauty of its lakes,

streams, and forests derives from the microclimates and varied

topography and soil produced by mountain-building and mountain-eroding

forces.

|

Overthrust Mountains

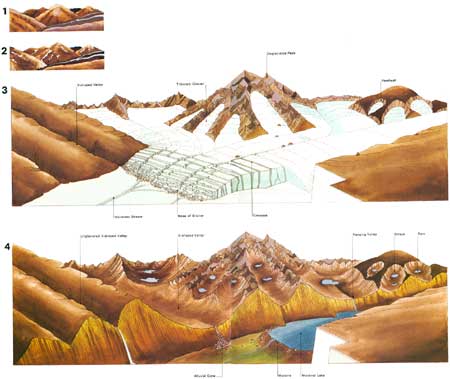

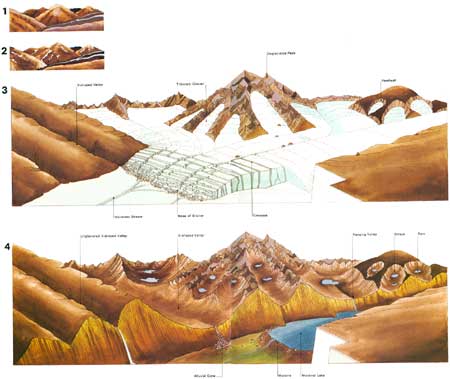

1 A hypothetical block of the Earth's crust in the region of

Glacier National Park as it existed more than 60 million years ago. The

two layers shown actually represent many strata of sedimentary

rocks.

2 Lateral pressure begins to force the rock layers to

buckle.

3 A large fold has been created, forcing the rock strata to

double over and overturning some layers. A break, or fault, is

forming at the plane of greatest stress.

4 The break has been completed and the strata west of the fault

have slid eastward, up and over the rocks east of the fault.

5 The Glacier landscape today. Throughout the millions of years

during which the folding, faulting, and overthrusting have been taking

place, the process of erosion has continued; a thousand meters of

stratified rocks have been worn away, so that only a remnant of the

overthrust layers can be seen today. Because Glacier's eastern slope

represents the eroded face of the overthrust block, the mountain range

rises precipitously from the prairie, with no foothills breaking the

abrupt transition from open prairie to mountain valley.

(click on above image for an enlargement in a new window)

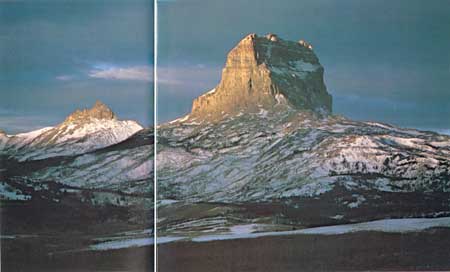

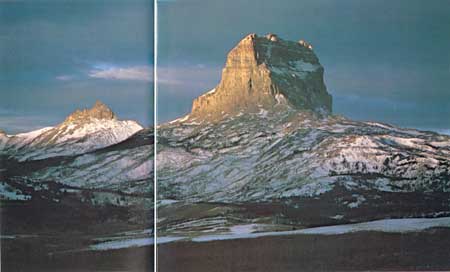

The peaks in this photograph (a view to the northwest from Marias Pass)

are remnants of the overthrust block, which moved eastward. The dividing

line between the light-colored rocks and the gray talus slopes beneath

them is the Lewis Overthrust Fault.

|

Glaciation

1 This is how the landscape in this region might have appeared

before the onset of the Pleistocene, millions of years ago. Note the

stream-eroded, V-shaped valleys. The climate at that time was

dry.

2 Glaciers began to form high on the peaks, crept downward, and

joined to form larger glaciers.

3 After many centuries of glaciation, tributary glaciers have cut

back into the peaks, forming basins called cirques. Thick

glaciers, moving rapidly and carrying rock fragments, have abraded the

main valleys' floors and sides, widening and deepening the valleys into

characteristic U-shapes.

4 In the present landscape, free of all but remnant glaciers,

small lakes called tarns occupy many of the cirque basins; and

waterfalls plunge into the main valleys from higher, shallower,

tributary valleys, called hanging valleys. Alluvial

cones—recent accumulations of rock debris—have begun to

build along the valley walls. In the main valley, a moraine (a

deposit of rock materials left by the retreating glacier) has formed a

dam that holds back a large lake.

During all this time, all parts of the terrain not buried under ice and

snow have been weathered and eroded by nonglacial forces. Thus the

contours of the jagged peaks and sheer cliffs have been

softened.

(click on above image for an enlargement in a new window)

Glacial landforms can be identified in this view of the Mokowanis Valley.

|

|

|

|