|

GLACIER National Park |

|

|

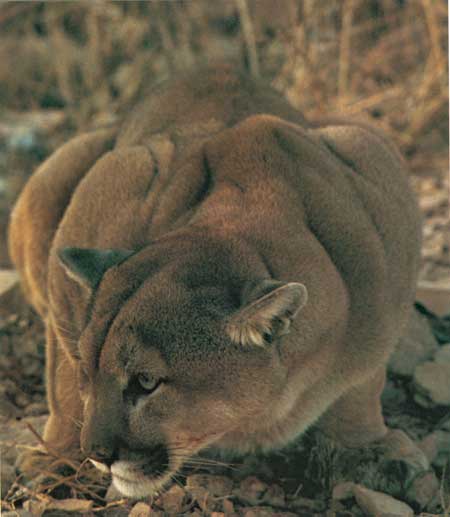

The Vital Predator The merciless law of predation might at first thought seem cruel; but the predator plays a vital part in maintaining the balance of the biotic community. Without the controlling factor of predation, prey species quickly enlarge their populations. If plant eaters are not checked, the resulting excess population exceeds the carrying capacity of the range. Food supply rapidly diminishes. In a damaged range, competition and stress result, usually culminating in a massive die-off through starvation and disease. Ironically, predators thus provide a service to their prey. First to fall to the predator are the old, the diseased, the unwary, and the young. By removing many young and old deer from a typical herd, cougars lessen competition among the deer for choice range, thus tending to keep herbivore numbers at parity with the land's carrying capacity. Only the strongest and wariest deer survive, ensuring that the fittest will continue the species. When man upsets this delicate balance—destroying predators in the hope of increasing numbers of game animals—the result is ecological disaster. In the 1930s, in a misguided attempt to "preserve" the whitetail deer herds of the park's North Fork area, many coyotes and cougars were exterminated. In 1935 alone, 50 cougars were killed. Relieved of the pressure of predation, the deer flourished. In a few years, however, the normally adequate range was severely overbrowsed. Suffering also from this imbalance were wapiti ("elk") and moose, ungulates that share the winter range with deer. Some predators are more specialized than others. The Canada lynx, for example, has oversize feet, an adaptation that helps it move across deep snow without breaking the surface. As a result, it is an efficient predator of the snowshoe hare, another large-footed animal. Relying on this adaptation, the lynx feeds almost exclusively on snowshoe hares. Consequently, its numbers inevitably fluctuate with the 10-year "boom and bust" cycle of the snowshoe. The coyote, on the other hand, is a generalized predator, exploiting whatever prey is currently abundant. Should mice or ground squirrels be in short supply, it will subsist on anything from grasshoppers to berries until favored prey again becomes available. (Animals that normally eat both plant and animal food are referred to as omnivores.) Generalized predators are thus better equipped to survive temporary ecological imbalances, maintaining their numbers at relatively consistent levels from year to year. Carnivores all, the animals on these pages illustrate various adaptations for capturing prey.  The population of the canada lynx, which is widely distributed in Glacier's coniferous forests, fluctuates in cycles. The lynx is abundant or scarce depending on the population condition of its chief prey, the equally cyclic snowshoe hare.  The cougar, which feeds primarily on deer, requires a large territory. Because of its strength, stealth, and speed, American folklore has given this wary cat a false reputation as a man-stalker.  The red fox depends largely on a well-developed sense of smell to locate its prey; it also relies on its keen eyesight, speed, and agility to capture mice, hares, birds, and whatever else it can run down or surprise.  To feed its demanding young, the Swainson's thrush hunts for insects along the forest floor and in the dense underbrush. This thrush relies on its secretive behavior to protect its nest near the ground from detection by other predators.  Armed with enlarged forelegs, the crab spider waits on or near flowers to ambush visiting bees, files, or other insects. Its venom produces a quick kill, allowing it to attack insects many times its own size.  The spotted frog is a large-mouthed predator that not only eats water striders and other insects but also gulps down smaller frogs and small fish. |

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |