|

ROCKY MOUNTAIN National Park |

|

Animal Life (continued)

COLD-BLOODED ANIMALS

Many creatures inhabit the earth which do not possess an adequate mechanism for maintenance of even body heat. Some of these animals, taking advantage of the slowness with which water changes temperature, live mostly in an aquatic environment. Few such creatures can endure the high altitude and cold winters of the park area.

Unlike other animals in national parks, fish may be taken by hook and line under regulations which are designed to conserve the resource. As long as you have a State fishing license, you may exercise this privilege in Rocky Mountain National Park. The season and catch limits vary from year to year, and you are urged to ask a park ranger about the current regulations.

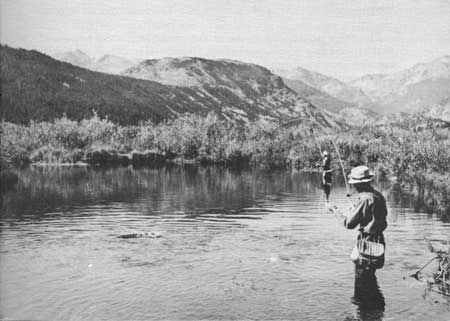

FISHING IS A POPULAR RECREATION MADE DOUBLY ATTRACTIVE BY THE MOUNTAIN SETTING OF THE PARK WATERS. |

The original trout in the park is the BLACK SPOTTED, or CUTTHROAT, TROUT. Once found only in the northern Rockies, it has been transplanted widely. It has numerous subspecies and color variations, but here it is usually an olive-green on back and upper sides, shading into a yellowish cast on lower sides. The lower surface becomes red at spawning time. The body and fins are black-spotted. The red streak on both sides of the lower jaw have given it the name "cutthroat." Its principal foods are flies, insects, and small aquatic animals. Spawning takes place in midsummer in the high country.

The BROOK TROUT has been introduced here. Originally not found west of the Mississippi, this trout has been planted all over the West. Its color is olive-green to gray; its sides are sprinkled with red and gray spots; and the fronts of the lower fins and the lower edge of the tail have a distinctive white border. It is not a true trout, being a "charr," but trout fishermen are happy to catch it. Its food includes insects, worms, small minnows, and crustaceans. This trout spawns in autumn, the female preparing the nest by scooping out a depression in the sand. After the eggs are fertilized, the female covers them with sand and gravel and leaves them to hatch out alone.

The RAINBOW TROUT is another nonnative trout of the park waters. Its original range was on the Pacific slope of the Sierras and the Cascades, but it has been transplanted widely. Its color is bluish-olive above the lateral line, but shades into silvery-green on the sides. A broad reddish band along the sides has given it the name "rainbow." Its food includes flies, insects, worms, minnows, and smaller fishes. It is a favorite of the angler for its fighting ability and tendency to break water when hooked. Spawning takes place from autumn to spring, depending on the altitude.

The most common amphibian in the park is the LEOPARD FROG. It varies in color from bright-green to tan, depending on the background. Restricted to damp areas near ponds or creeks, it is most likely to be seen in spring and early summer when the gelatinous masses of eggs are being laid. The tadpoles develop into mature frogs in about 3 years. Until then, the diet is vegetarian; after maturity, insects and worms are eaten. This little frog is found in Moraine Park, Horseshoe Park, and other moist grassland valleys.

The THREE-LINED TREE FROG is our smallest amphibian—only an inch or so long—and often is mistaken for a young leopard frog. Although it is one of the tree frogs and possesses disks on its toes, it is seldom seen in trees, preferring small ponds or swampy grassland. It is sometimes found under rockpiles or pieces of damp wood. Despite its small size, its loud chirps in spring and summer can be heard a half mile away. During its singing, a vocal sac beneath the lower jaw inflates to a size larger than the creature's head. It is easily recognized by the three stripes down its back. Gem Lake is a good place to see this diminutive amphibian.

The MOUNTAIN TOAD is a nondescript denizen of marshy lake vicinities. It is common in Cub Lake Valley, Hallowell Park, and in the Ouzel Lake area in Wild Basin. In late spring, large numbers congregate in ponds, where strings of eggs are laid. The small tadpoles become adults by the end of the summer. This toad feeds on insects.

The TIGER SALAMANDER is one of the oddest animals of the park. Salamanders do not walk out of fires, as medieval tradition had it, but are amphibia, like frogs and toads, except that they retain their tails after reaching maturity. The young hatch from eggs and live in shallow ponds, breathing by means of feathery external gills attached at the back of the head. Later, the gills are absorbed and the salamander begins breathing by means of lungs; it then leaves the water for a moist underground burrow, returning to ponds in early spring to lay eggs on plants or debris in the water near the shore. In southern latitudes, the larvae (gill-breathing forms) are able to lay eggs and are the axolotls of Mexico. Our local variety of the tiger salamander is about 8 inches long, gray-brown in color, with dark spots. It is found in Sheep Lake (from whence mass movements occur during spawning season) and is often seen in suitable habitats along the Cub Lake Trail. It feeds on insects, insect larvae, worms, and small snails. Although rather hideous in appearance, it is quite harmless.

The only reptile in the park is the MOUNTAIN GARTER SNAKE, which is found throughout the mountainous areas of Colorado. Because of its fondness for water, it is often erroneously called a "water snake." It has a greenish-gray color and may reach a length of over 2 feet. It feeds on frogs and worms and is entirely harmless to man, but it is capable of giving off an offensive odor when handled. The young are born alive in midsummer. These harmless garter snakes may be seen near most of the marshy ponds or slow-moving streams in the park. The ponds in Cub Lake Valley and in Hallowell Park are favorite haunts of these interesting creatures.

No rattlesnakes or other poisonous reptiles have ever been found in the park. Reports of rattlesnakes near Glen Haven mark the highest known occurrences in this region. This, no doubt, contributes to the visitor's peace of mind, but puzzles many people.

The absence, or relative scarcity, of cold-blooded animals is probably due to the climate. The long, cold winters, the chilly summer evenings, and the lower amount of oxygen at high altitudes are probably all contributing factors. On the tundra, for example, many of the pools are free of ice for only about 6 weeks—scarcely time for a frog's eggs to hatch and for the larvae to develop lungs before the water freezes again. The cold nights, even in midsummer, would inhibit a large snake's movements to such a degree that it would probably starve. The result is that you may hike in the park in complete freedom from possible poisonous snakebites.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |