|

SAGUARO National Park |

|

desert plants

When you look out over the cactus forest, in either part of Saguaro National Monument, you may think there's a sameness to it in all directions—saguaros standing amid scattered shrubs. But look harder, or walk about, and you will discover variations in the scene. First, there is a gradual change in the vegetation from the mountain foot down the bajada or pediment to the valley floor, as saguaros and paloverdes (green) become sparser and creosote-bushes (smaller and brownish) take over. (The monument itself does not extend far enough from the mountain bases to include extensive creosotebush communities, but these cover large areas in the lowest parts of the valleys.) Then there is the luxuriant growth along washes, where mesquites and paloverdes grow to tree size and there are more kinds of plants. And if you are observant you may notice slight variations with each change in slope on the rolling hills—for example, more grass growing on their north sides. On another scale, you can see separate little communities of plants in special situations, as under shrubs or on rocks.

These patterns are due to variations in the environment. For the desert is hotter and drier in some places than in others. The gradual downslope changes in vegetation reflect the decrease in the amount of soil moisture available to plants—a condition caused by the decreasing size of soil particles and consequent shrinkage of water-holding space between particles. Desert washes encourage plant growth because they channel water and cold air. Strangely enough, night temperatures are often lower in a desert valley than farther up the slopes. This "inversion" is due to drainage of cold air down mountainsides, forming cold "pools" in valley bottoms, especially in winter. Cold air is heavier than warm, and (since air flows much like water) it is channeled down the draws—a fact that will strike you if you walk into a wash near the mountains at night or early in the morning. Add this phenomenon to the great amounts of moisture that lie beneath the surface of washes, and you can see that desert drainageways are really linear oases. More subtly, desert hills reflect in their vegetation the differences in soil moisture from north slopes to south slopes caused by increasing exposure to sunlight.

Saguaro Forest landscape from the scenic drive. |

One controlling factor, then, is dominant in the desert: the scarcity of water. This results not only in the unusual forms and adaptations of desert plants, but also in a distinctive type of plant community. In wetter climes, plants compete mostly for sunlight. They can grow close together, as long as they receive adequate illumination. During the regrowth of forests, several distinct sets of plants appear, each succeeding group more tolerant of shade than the last, as the forest canopy closes. In the desert, there is no such succession. Clear a patch of desert vegetation, and the same species will reappear—spaced out, with bare ground between them as before. For here sunlight is abundant (we might say overabundant), but there is not enough water to allow plants to cover the ground.

Dr. Forrest Shreve, who was a botanist at the Carnegie Institution's Desert Laboratory near Tucson and a master student of deserts, defined a desert as "an area in which deficient and uncertain rainfall . . . has made a strong impression on the structure, functions, and behavior of living things." The distinctive characteristics of desert plants and animals have evolved through millions of years, in a trial-and-error process in which only the better-fitted forms have survived. It would be enlightening to know how many of the species and varieties of plants that developed during the past 60 million years or so have failed to adapt to Sonoran Desert conditions. It is fascinating to study the hundreds of forms that have succeeded and to try to determine what structures they have perfected and what methods they have originated that enabled them to maintain themselves in such a harsh environment.

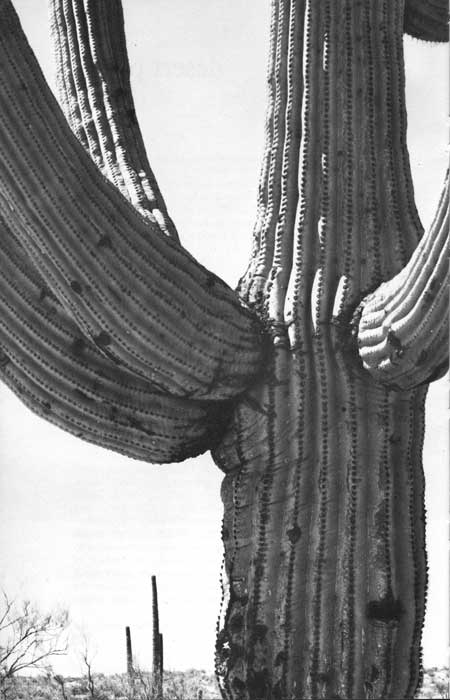

Desert plants can be classified as "escapers," "evaders," and "resisters," according to their means of adaptation to water shortage. Escapers, such as the annuals, avoid the problem entirely by waiting out the dry periods as seeds, to sprout and reproduce only when the rains come. Evaders, such as the ocotillo, reduce their water loss during droughts by such methods as dropping their leaves or going into a state of dormancy. Resisters, however, "hang in there" all year, taking the desert's worst. The cactuses, prime examples of this group, rapidly soak up water from each rain and store it for use during drought; the mesquite's deep roots tap a more constant source of moisture.

(Photo by Freg E. Mang, Jr.)

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |