|

SAGUARO National Park |

|

the impact of man

Man has been a part of the scene in this region for several thousand years, but until recent times his influence on it was minimal. Only with the rapid technological development of the last century has man been able to make a major impact on this landscape. Thus the story of man, here as elsewhere, is a story of gradually accelerating power to change environments, a power that now threatens to destroy environments, and with them man himself.

From carbon-14 dating in Ventana Cave, we know that man was here at least 12,500 years ago, in the Pleistocene age, a time that was cool and moist compared to the present. Living by hunting, he followed mammoths and other large mammals. As the climate warmed during succeeding millenniums, and these mammals became extinct, he came to rely more on plant foods. These hunters and gatherers necessarily had to live in small bands scattered over the land, since the plants and animals on which they depended were widely dispersed. By 300 B.C., they had learned from people to the south how to cultivate food plants, and had developed a sedentary way of life. About 2,300 years ago a group we call the Hohokam settled in the Salt and Gila River basins (including the Santa Cruz Valley). By A.D. 700 they had a well developed agricultural economy including extensive irrigation systems. Pottery fragments, projectile points, petroglyphs (rock carvings), and other evidence show that Hohokam villages existed for about 600 years in the eastern section of the monument along Rincon Creek and its tributary washes. Archeological work in the Tucson Mountain Section has indicated that this area was visited only temporarily by the Hohokam, for hunting, food gathering, and perhaps ceremonial purposes.

During the 15th century the Hohokam high culture vanished. Soils made salty from irrigation water and internecine warfare are suggested explanations.

When the Spanish explorer Coronado passed to the east of the Rincons in 1540, he found the Sobaipuri living there. The Pimas, descendants of the Hohokam, occupied the same basins the Hohokam had. To the west, in drier country, lived the Papago. These tribes, thought to be descendants of the Hohokam, lived much the same sort of life, practicing irrigation where surface water was available, hunting and gathering where it was not.

The period of Spanish rule, implemented by a series of missions, began in the Santa Cruz Valley about 1692, when the energetic Father Kino began his work among the Pima and Papago. The mission system concentrated the Indians in fewer places, brought Spanish and, later, Mexican settlers into southern Arizona, and introduced sheep, cattle, and goats. Although the new culture must have had some environmental effects, there is no evidence of drastic change. Grass was plentiful, and streams, including the Santa Cruz, remained marshy and unchanneled.

After the Gadsden Purchase of 1853-54, however, when the present boundary with Mexico was established and this area came into United States ownership, man's impact on the land increased. Apache raiding had been a deterrent to settlement during the 18th and 19th centuries, but, after the Civil War, American soldiers got the upper hand and settlement increased. Following completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad to Tucson in 1879, a cattle boom began. The disastrous results of the livestock explosion of the eighties—overgrazing, soil erosion, and starvation of cattle—we have already seen in the story of the saguaro cactus. In 1890, a flood cut a deep channel in the Santa Cruz River, transforming it from a meandering, marshy stream to the usually dry incision one sees today. The arroyo cutting of this and many other rivers throughout the Southwest was undoubtedly due partly to increasing aridity, which reduced the plant cover and its water-holding capacity. But the erosion was probably triggered by overgrazing.

In the monument, we have already seen how grazing pressure, hunting, and predator control reduced ground cover and led to an upsurge of certain rodents and a decline in large mammals. But there have been other man-induced changes. For as long as there has been forest on top of the Rincons, there has been fire. Lightning-caused fire is a natural part of ponderosa-pine forest, every few years burning the litter and small trees and shrubs from the forest floor, and thus maintaining open stands of tall trees. But since 1908, when the Rincon Mountains came under protection of the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (to be followed in 1933 by National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior protection), fires have been put out as fast as possible. This policy has resulted in a paradox. On the one hand, thickets of scrawny young pines and shrubs such as buckbrush have developed in many places under the tall pines. On the other hand, the accumulation of litter and low-level vegetation has provided fuel over the years for occasional very hot crown fires, which have been hard to control and which have burned large acreages. On top of the Rincons you can see several meadows that resulted from these fires. Only a few scattered trees and stumps remain in them to suggest the forest that once was there.

Ideally, national parks and monuments should be "vignettes of primitive America"—naturally evolved landscapes in much the same condition as when first seen by Europeans. In reality they are compromises—beautiful, wild, but still bearing the marks of human occupation. In Saguaro, as we have seen, fire control has produced a forest different from that known to the Indians who once lived here; grazing has depleted the ground cover; and hunting has removed the desert bighorn from its rocky haunts. In these days of burgeoning population, when human influence is affecting every natural landscape, environmental management becomes necessary to approach the ideal of naturalness. This may mean "prescribed burns" to return forests to their earlier state; elimination of grazing; or reintroduction of animals once native to a park. In the summer of 1971, after 2 inches of rainfall, natural burns (caused by lightning strikes) were allowed to run their courses.

Some or all of these measures may be taken in Saguaro, in order that future generations will know a piece of the Sonoran Desert as it was in Coronado's time.

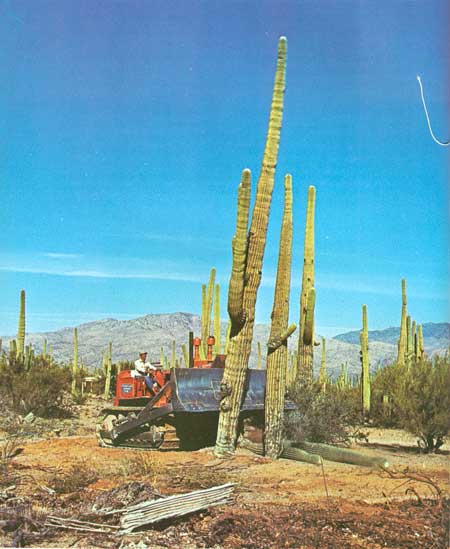

(Photo by George Olin)

The realization of this goal, however diligently we work toward it, seems almost each day to become more difficult of attainment. These desert and mountain environments—which once seemed secure, needing only the continued protection afforded by their status as a national monument—are increasingly imperiled by the works of man. As the city of Tucson sprawls in all directions, the monument's two divisions, islands in an encroaching sea of civilization, must withstand ever-accelerating hazards. Vandalism takes an increasing toll of the saguaros; housing developments creep toward the monument borders. Smog drifts over the fragile plant communities, threatening to choke them—as the polluted air from Los Angeles is already strangling forests in the distant San Bernardino Mountains.

A new awareness that the best-managed preserve cannot thrive independently of what is happening in the surrounding region only emphasizes the difficulty of the task. Saving the saguaros is inevitably tied to the problem of enhancing the quality of life and reversing the degradation of the environment—not only in Tucson but throughout the Southwest.

There is no time to waste. Only concerted effort by scientists, resource managers, and the community can assure that our grandchildren will be able to visit a Saguaro National Monument where coyotes howl under the moon, peccaries snort through the washes, and giant cactuses lift bristly green arms into a blue sky.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |