|

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS National Park |

|

The Mountains Appear

If you stand on one of the lofty peaks of the Great Smoky Mountains and view the wavelike sequence of ridges which finally lose themselves in the hazy distance, you are awed by the grandeur that nature has lavished upon this mountainous region. Its landscape is the product of almost incomprehensible forces. Here, throughout countless ages, the surface of the land has undergone profound change. The main story has been one of erosion, but let us go back many millions of years and begin the geologic account with the rock-making and the building of the mountains which took place in another age, for the Smokies are a part of the oldest range of mountains in the country.

Most of the rocks that compose these mountains belong to a group called the Ocoee series. They were formed from sediments—muds, sands, and gravels—derived from a very ancient land mass and deposited in great quantities, probably on the floor of a shallow sea. Here they gradually accumulated in extensive layers to a thickness of 20,000 feet or more. Deep burial and compaction, plus the chemical action of water depositing natural cement among the particles, changed the sediments to rock.

So ancient are these Ocoee rocks that they contain no fossils of plants or animals, having been formed before life was abundant on the earth. According to geologists, these rocks antedated the Cambrian period of the Paleozoic era, more than 500 million years ago.

Mount Le Conte (elev., 6,593 ft.), as seen from Newfound Gap. The prominent scars on the side of this mountain resulted from a cloudburst which occurred on September 1, 1951. Most of the dark-colored, spired evergreens are red spruce. Courtesy, Tennessee Conservation Department. |

The vast thickness of the sediments and the theory concerning their source captures the imagination. What was it like, this land mass from which the silts, sands, and gravels were derived?

Some of the rocks of the Ocoee series . . . are made up of innumerable pebbles of quartz and feldspar; these pebbles were derived from the breaking apart, under the influence of weather, of individual crystals of an ancient granite mass. The conglomerate looks somewhat like granite and is composed of the same materials but these materials have been broken up, transported, reconstituted in strata, and once more consolidated. The granite from which the conglomerates were derived probably stood as mountain ranges at the time when the Ocoee series was being formed. (See "Selected Bibliography," King and Stupka, 1950.)

The accumulation of sediments extended over long periods in geologic time. Following this, the land surface was raised and subjected to tremendous lateral pressures which caused the rock formations to buckle into folds and to break in many places, forming overthrust faults. This major disturbance of the earth's crust is known as the Appalachian revolution, an epoch of mountain-building in the Eastern United States which transpired some 200 million years ago. The uplift that brought the higher Rocky Mountains into being came at a much later time.

The overthrust of rock formations is well exemplified in the scenic valley of Cades Cove. Here the Ocoee rocks were thrust several miles, causing them to override much younger formations in the valley section to the north. Those younger rocks, mostly limestones, were formed during the Ordovician period of the Paleozoic era. In contrast to the older, lifeless Ocoee series, the younger rocks contain fossil remains of primitive sea animals. In the ages following the overthrust, constant stream erosion gradually cut through the ancient rocks and revealed the younger limestones beneath. Even though all rocks exposed to the weather are altered, not all are equally susceptible; thus the limestones, once exposed, weathered and eroded with comparative rapidity, producing a level-floored valley almost entirely surrounded by steep-sided mountains. Today in this scenic cove you can stand almost encircled by mountains composed of rocks 200 million years older than the rocks of the valley floor.

Following the Appalachian revolution and the uplift of the land, the relentless forces of rock-weathering and erosion began carving the valleys. This was evidently renewed several times; each time erosion reduced the entire region to an almost featureless plain, but again the processes of cutting down were renewed by uplifts in the land. Evidence of these ancient plains can be seen as a series of high ridges of approximately equal height. The valleys as we see them today have been carved from what was once a much higher land surface. Geologists explain it in this manner:

The present ridges and mountains are not caused by upheaval, but by erosion, whereby the valleys have been carved out of the same rock formations as those that still project above them. One may therefore conclude that the landscape of Great Smoky Mountains is not made up so much of ridges rising between the valleys as of valleys cut between the ridges (King and Stupka, 1950).

Your appreciation of the landscape will be increased by an awareness that these valleys were carved by stream erosion, a phenomenon we witness almost daily. Every year thousands of tons of soil and rock fragments are washed down the slopes and are carried away by the streams. Usually, this is a very slow process, but there have been cases of tremendously accelerated erosion, when tons of material have been removed in a matter of minutes. On the south face of Mount Le Conte are huge scars which bear testimony to the tremendous force of flood waters. Here a cloudburst caused complete destruction to parts of a mature forest, stripping large trees from the mountainside and piling up debris for miles in the valley below.

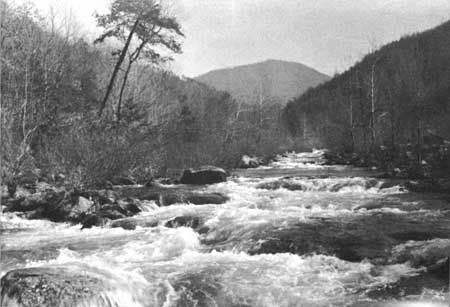

Little River, one of many fine trout streams in the park. These cold, rock-strewn watercourses are, for some visitors, the outstanding attraction in the area. |

It is intriguing to imagine the enormous amounts of sediments that have been removed through the ages to produce the valleys that we see today. When we consider the present depth of the valleys and the fact that these mountains stood thousands of feet higher in the geologic past, we get some idea of the grand scale of erosion in this area. As one geologist, George H. Chadwick, has stated, "Even the Grand Canyon fails to dwarf what is here visible."

In the time of the last geologic epoch, the Pleistocene, glacial ice spread over a large part of the land surface of the world. It covered Canada and extended into the northern United States. During one period, the ice sheet moved as far south as the Ohio River, but it never reached the Great Smoky Mountains. Perhaps, during the ice ages, the highest ridges of the Smokies were bare of trees and were covered with snow. The cold climate of that time left its mark upon the landscape in this area. The huge boulders, or "graybacks," lying on the slopes and in the valleys were moved there by forces that are no longer evident. It appears that these rocks were broken off and removed from the mountaintops by frost action, and they gradually accumulated as boulder fields on the slopes and in the valleys below. You may see examples of such boulder fields along both the Big Locust and the Buckeye Nature Trails, adjacent to U.S. 441.

As the great Pleistocene ice moved slowly southward, many Canadian-zone plants and animals migrated before it and found a haven in the southern Appalachians, well beyond the limits of glacial ice. In the Great Smoky Mountains, most of the species of forest trees survived the rigorous climate which prevailed. Here, in the heart of the deciduous forest region of Eastern North America, there are more kinds of native trees than in any area of comparable size in the United States. In fact, in all of Europe there are not many more tree species than grow in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The outstanding attraction of this area is its flora; so profusely does it grow that it covers the mountains everywhere with an unbroken mantle. There is no timberline here, and rock exposures are uncommon. But beneath the living layering of green, and the thin crust of soil which nourishes it, is the great mass of solid rock which has no life and whose secrets have become dimmed through unnumbered centuries.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |