|

ORGAN PIPE CACTUS National Monument |

|

Higher Elevations, Botanically Unexplored

ACCESSIBLE BY ONLY a few unimproved trails, the rugged upper slopes of the Ajo Mountains and Growler Mountains have been visited principally by Indians, local stockmen, park rangers, and rock climbers—and not many of them. Reports regarding the vegetation are correspondingly scarce and meager. The steep and rocky nature of the terrain provides little opportunity for plant growth, and lack of moisture further restricts the vegetative cover.

None of the mountain ranges are high. Santa Rosa Peak, in the Ajos, highest mountain in the monument, rises to only 4,829 feet. Kino Peak, tallest in the Growlers, is only 3,057 feet high. Elevation in the monument, therefore, although influential, does not have as much effect on climate and hence on plant and animal life as it would if the mountains were higher.

Occurring as scrubby individuals or in small thickets, the common one-seed juniper is found on the slopes of higher mountains in suitable locations.

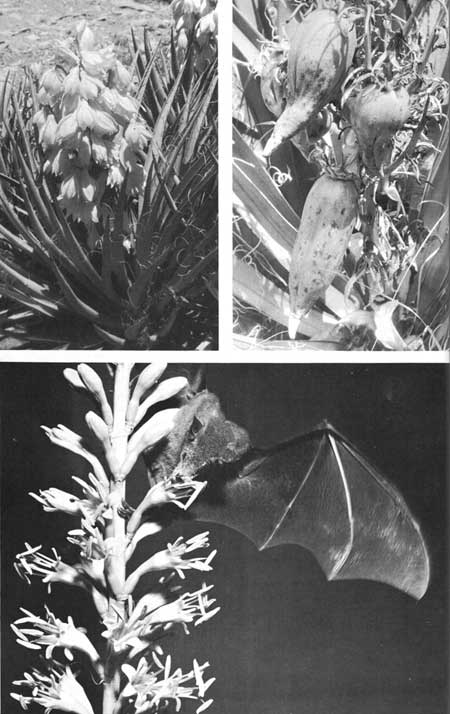

Datil yucca (above) and Schott agave are two interesting plants of the upper slopes. Desert Indians once used the yucca's leaf fibers in weaving coarse fabrics, and they still eat the roasted fruits. Below, a long-nosed bat sips nectar from agave blossoms. |

On dry, sunny benches of the Ajo Mountains around 3,000 feet are occasional colonies of the rather rare Schott agave, or centuryplant, reaching here the western limit of its known range. One of the leaf succulents, the centuryplant derives its name from the fact that many years are required for it to store enough food in its thick rootstock to produce a rapidly growing blossom stem and dense head of flowers. Completely exhausted by this supreme effort, the plant dies after the seeds have matured. This species is reported to be pollinized by the long-nosed bat.

The Ajo and Growler ranges provide a variety of habitats for groups of plants requiring special conditions of shade, moisture, exposure, and slope that are found only in mountain canyons of desert regions. One of the not uncommon associations of desert-mountain plants is the oak-gooseberry-penstemon community.

Oaks in the monument include shrub live oak, gray oak, and the rare Ajo oak. Gray and shrub live oaks, which are similar, form thickets on moist, protected, usually north-facing canyon walls along with the evergreen shrub, Torrey vauquelinia, or Arizona-rosewood. Mingling with these is the lower-growing oakwoods, or yellow-flowered gooseberry, which blooms from November to April. Taking advantage of shade provided by thickets of either juniper or oak, the littleleaf penstemon, or yellow beardtongue, brightens mountain slopes from March to May.

On the more exposed higher slopes of the mountains, the datil yucca occasionally may be found, often associated with scrubby junipers. In April-May this wide-leafed member of the lily family produces short robust stalks of creamy bell-like flowers. These mature to large pulpy fruits, which are relished by rodents and other animals. Because its roots contain saponin, the yucca is sometimes called soapweed.

Five species of ferns have been recorded in the monument: one each of lipfern, goldfern, and cliffbrake, and two species of cloakfern. All of these are found in relatively dry, rocky locations at elevations (except the cloakferns) from 2,000 feet to the tops of the mountains.

A host of shrubs grow in tangled profusion around occasional seeps in the canyon bottoms. A variety of shrub species is also found on the mountain slopes where there is enough soil to hold the roots. Some furnish browse for deer and bighorn, while others provide shelter for birds and small mammals. Among the common shrubs are redberry buckthorn, Mexican condalia (bluewood), skunkbush sumac, Texas mulberry, spiny hackberry, and desert-olive forestiera.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |