|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

We Stand On The Past

Early in our visit to Isle Royale we set out to climb up through the enclosing forests to a ridgetop, from where we can see the lay of this island and try to grasp it whole. After making camp at Daisy Farm on Rock Harbor, we start up the Mt. Ojibway Trail. Spruces, firs, and birches rise above us. For a little stretch our feet slip on rounded stones. Up the south side of Ransom Hill, where the forest opens and the trail steepens, we breathe a bit harder. Down the hill's more abrupt north side, where the white columns of paper birch surround us, we apply the brakes a bit. Now our boots thump on the simple bridge across Tobin Creek, which has been widened and deepened by a dam built by beavers somewhere downstream. Then up and over another hill, across the outlet of Lake Ojibway, and we make a longer climb toward Mt. Ojibway, a promontory of Greenstone Ridge. The forest thins, clumps of small maples appear, and as we gain the smooth-rocked grassy top of Mt. Ojibway and ascend the fire tower, the island opens before us. We see a strikingly striated pattern of land and water—elongated, parallel forms that might have been created by a giant comb raking the emergent rocks in a northeast-southwest direction. Parallel ridges, dominated by the island's backbone—Greenstone Ridge—state the theme most boldly. Where the ridges reach Lake Superior they continue underwater, sometimes emerging to form narrow islands. The long, linear troughs between ridges hold here and there a stretched-out lake; and where the valleys reach the big lake they form long, deep coves. Plant distribution accentuates this parallel pattern. Light green aspen and birch dominate many ridges, while dark green coniferous forests lie in the troughs. Stretching along some ridgetops are open strips of grass and shrubs, through which the underlying rock mass often outcrops. Fifteen miles to the north, the mesa-like shapes of Thunder Cape rise along the Canadian shore, close to but irrevocably separated from the island by the cold, plunging depths of Lake Superior.

(Photo by R. Janke)

All of it—the hills we sweatingly crossed, the forest scenes we glimpsed, the overall pattern itself—is the legacy of past events. The varying composition of the forest has been dictated by the topography, shaped slowly over eons by forgotten fires, by storms of yesteryear, by centuries of animal activity, and by a thousand little colonizations and extinctions during the island's history. The stones we slipped on near the start of our hike are an ancient beach formed by an ancestor of Lake Superior. The island's lakes owe their existence to great, gouging glaciers that thawed only a tick of geological time ago. And our legs ache today because the processes that formed and eroded the rocks millions of years ago created a corrugated topography.

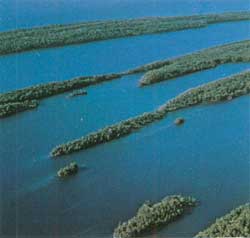

The Amygdaloid Island region of the park strikingly displays the ridge-and-trough topography of the archipelago. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

The surface scene that spreads before us—lakes, forest, and the life-giving soil—is the work of 11,000 years, a very short time by nature's standards. During those one hundred and ten centuries the island appeared from beneath glacial ice; rose as the lake level dropped; was colonized by plants and animals; developed a little soil and a heavy, ever-changing forest; and experienced the beginning and inevitable shrinking of its many inland lakes.

Yet the creation of the rocks and the development of their ridge-and-trough pattern are the work of millions of years—a span of time in which the formation of Lake Superior and its islands is only the most recent event. The earth's oldest rocks, representing seas and mountains that gradually appeared and disappeared, lie thousands of feet beneath the thick deposits that make Isle Royale. The island's rocks date from a later episode, the formation of the Superior Basin, which was to shape all subsequent geologic events in the region.

Some 1.2 billion years ago, the earth's crust cracked along a great rift zone that stretched through the middle of the area now occupied by Lake Superior and may have bent southward toward the present Gulf of Mexico. Through this series of cracks poured molten lava, forced up by pressures deep within the earth. A hundred times or more, flaming sheets flowed out from the fissures, eventually covering thousands of square miles. As they did, the land along the rift zone sank, forming a basin. In the quiet periods between flows, rock material was washed from the rim of this great basin toward its center. After the last eruption, streams continued to carry boulders, pebbles, sand grains, and fine silt from the rim hills down toward the still-sinking basin plains. These events left a rock record consisting, beneath, of thick layers of volcanic rock alternating with thin layers of sandstone and conglomerate (composed of rounded rock fragments cemented together by finer material), and above, of several thousand feet of the last two types of sedimentary rock. These rocks—volcanics sandstone, and conglomerate—form the bedrock of Isle Royale, with the volcanic basalt predominant on most of the island and the reddish sedimentaries forming the surface in the Feldtmann Ridge-Big Siskiwit River area. The arrangement of these rocks in layers and their differing resistance to erosion dictated the island's present ridge-and-valley topography.

Molten rock forced between layers of dark basalt formed light-colored dikes like these at Conglomerate Bay. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Some time after these layers were deposited, new pressures in the earth forced hot, mineral-bearing solutions up into the cavities and cracks in the rock. One of the minerals thus deposited was copper. Occurring in its pure or "native" state, the veins and masses of copper lay within the rock, until the far-distant time when man would come hunting it. Those who walk the island's narrow pebble beaches can see other minerals—such as quartz; white, red, or yellow heulandite; white or yellow stilbite; and banded agate—which filled gas bubbles within the basalt and eventually were broken free by the pounding waves.

Some time, also, after formation of the Superior Basin, faulting—displacement along a crack in the earth's crust—occurred, thrusting some sections of it upward and adjacent sections downward. One of these faults ran along what is now the center of the Keewenaw Peninsula, on the Michigan shore. Another is thought to have opened along the north edge of Isle Royale, which would account for the present projection of this piece of land above Lake Superior. Lesser faults cracked across the island, forming such depressions as McCargoe Cove and the valley that is followed by a section of the Huginnin Cove Trail.

McCargoe Cove occupies a depression formed by a diagonal fault in the north east part of Isle Royale. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

Between the deposition of Isle Royale's uppermost conglomerate and the work of the most recent glacier there is an enormous gap in the geologic record. Whatever deposits were laid down during those millions of years were subsequently eroded away, leaving the layers we have described to form the land's surface. Depressed in the center of the Superior Basin, these layers rose toward the basin's rim, where their edges were exposed in parallel bands. The bands of sandstone and conglomerate, being less resistant than the volcanic basalt, eroded faster. Streams tended to flow along the depressions started in these more vulnerable rocks, gradually deepening them. In this way, Isle Royale's bands of basalt remained higher to form ridges, while valleys developed on the sandstone and conglomerate between them. The south slopes of ridges remained fairly gentle, following the dip of the layers toward the center of the basin, while north slopes—the eroded edges of layers—dropped off steeply.

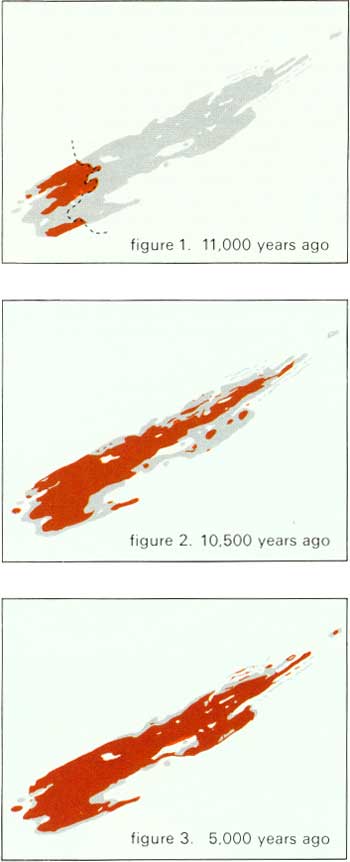

Since the last glaciation, Isle Royale has gradually been emerging from lake waters as the land rebounds from its depressed state under glacial ice and the ancestral Great Lakes cut successiveiy lower outlets. Figure 1 shows the position of the glacier's edge (dotted line) about 11,000 years ago, with the exposed western end of the island shown in brown. The gray area represents the present extent of Isle Royale. Figure 2 shows the island about 10,500 years ago, during the Lake Minong stage. By 5,000 years ago (figure 3), in the Lake Nipissing stage, Siskiwit Lake (on the south shore) had been cut off from the big lake and the island had nearly reached its present configuration. At the rate of a foot or more per century, the land continues to rise today. (Diagram by Betty Fraser, based on drawing by Robert Johnson) |

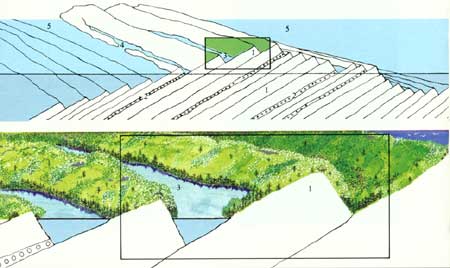

Geologic events have strongly shaped the present character of Isle Royale. A series of lava flows, beginning some 1.2 billion years ago, formed the predominant rock of the island (1). During quiet periods between flows, sand and gravel were deposited in the subsiding Superior Basin and now form thin layers of sedimentary rock (2) between the lava flows. Subsidence in the basin's center produced tilting of the layers near the rims; on Isle Royale the rocks dip southeastward at angles ranging from 5 to 50 degrees. Erosion, particularly of sedimentary rock, between the uptilted lava layers produced the long valleys that alternate with the ridges of Isle Royale. In some of these valleys, glacial scouring left depressions that filled to become lakes (3). Coves and harbors (4) occupy low-lying troughs, and still other rock layers lie beneath the waters of Lake Superior (5), perhaps eventually to be raised high enough to become new offshore islands or peninsulas. Walking across the island, you will notice that the north sides of ridges—the edges of rock layers—are decidedly steeper than the south sides, which follow the more gentle dip of the strata. Through its influence on soil and moisture conditions, the regular ridge-and-valley topography has strongly affected the pattern of vegetation and with it the distribution of animal life. Thus the nature of Isle Royale's rocks has touched all aspects of the island's natural history. (Diagram by Betty Fraser, based on drawing by Robert Johnson) |

Looking north toward the central high part of Isle Royale, we see Siskiwit Bay, a large body of water that freezes over in calm winter weather. The contours of Houghton Point, in the foreground, reflect the geologic origins of the Isle Royale archipelago. (Photo by Rolf O. Peterson) |

This pattern was accentuated and somewhat modified by the series of glaciers that rode down over the northern United States during the last million years. A cooling trend, accompanied perhaps by greater wetness, produced more snow across Canada during the winters than could be melted during the summers. As the snow accumulated, it was compressed into ice; and under pressure of the growing mass it finally began to move. Four major advances of these continental glaciers, separated by long intervals of mild climate during which the ice sheets melted, scoured the land as far south as the Ohio River. A large river valley is thought to have occupied the center of the Superior Basin during the glacial period and to have channeled the immensely thick lobes of ice flowing through that area. The last major glaciation, known as the Wisconsin, ended in the Superior area only a few thousand years ago, leaving behind the ancestral Great Lakes, thousands of smaller lakes, and deposits of rock debris thee glacier had scraped up and pulverized in its crushing advance.

Today on Isle Royale we can see many places where the ice, perhaps a mile thick, smoothed and rounded the rock, and other places where, pushing boulders over the bedrock, it carved long grooves. Running generally northeast-southwest, these grooves indicate that the glaciers moved mostly parallel to the ridges. Scouring the valleys deeper, the ice made depressions where lakes formed after its retreat. On the southwestern part of the island, where the last glacier paused in its retreat, are small, linear hills made of its deposits.

The dying of the last glacier led to the birth of modern Isle Royale. As it melted northward across the Superior Basin, which it had scoured and depressed, the ice formed a gigantic dam for its own meltwater, thus creating the first ancestor of Lake Superior. About 11,000 years ago, the ice front lay across the southwest end of that section of land we now call Isle Royale, leaving three-fourths of it buried under ice and the southwest quarter partly above and partly beneath the water. The shoreline then stood at about the present 800-foot contour. After a long pause at this position, the ice resumed its rapid retreat northward, leaving a thin mantle of deposits on the southwest end, where melting had been very slow, but very little material on the central and northeast sections, where melting had been rapid.

What did our island look like, newly relieved of its ice burden some 10,800 years ago? Studies by geologist N. King Huber indicate that about half of present-day Isle Royale projected above the water. Much of the southwest end was in one piece, but the northeast end tailed off to a long, thin peninsula flanked by island chains. Glacial till of sand, silt, and stones softened the contours on the southwest part and covered most of the bedrock, but toward the northeast most of the rock was exposed.

Like earth before primeval life, Isle Royale stood barren, waiting.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |