|

ISLE ROYALE National Park |

|

The Time Of Testing

Snow. Ice. Wind. Birches bare lines against the sky. Conifers green and full on the white hills. Silence. Now wind again. Hare tracks frozen across the trail. This is winter, the time of testing.

Bringing cold, wind, snow, and reduced food and cover, winter is indeed the most critical time of year for life on Isle Royale. But the island's plants and animals have a long time to prepare for it, since the slow-cooling water of Lake Superior warms the cold air above it until ice forms on the lake.

Fall may be considered to begin in August, when island birds begin migrating, and to end in late November, when snow usually falls in earnest. In mid-September, maple leaves start to turn red and yellow, and birches add their gold. Colors peak in the first half of October, as aspens, too, turn yellow. Then, with the first good wind, leaves fall. In October, brook trout, lake trout, and whitefish spawn. Moose, too, end the year with reproductive activity. The bulls have been getting more and more edgy since early September. They rub the velvet off their antlers in early September, and track down cows through late September and October. Their calls and grunts resound through the fall forest. Meanwhile, insect numbers have been diminishing rapidly. Mosquitoes have died out during August, flies in September. Most other insects are killed or go into hibernation during the frosts of September and October. Monarch butterflies, however, flutter south across Lake Superior toward the Gulf of Mexico, obeying the yearly command that pulses through their tiny nervous systems.

The period of late autumn and winter brings strong winds as well as low temperatures to Isle Royale. (Photo by Robt. G. Johnsson) |

By late November, when the white winter blanket has settled, plants are dormant; insects, reptiles, and amphibians are hibernating; and most birds have migrated. Most of the mammal contingent, however, faces winter head-on.

Of Isle Royale's current 15 species of mammals, only the bats hibernate or migrate to the south. To survive the winter, all others must find food and must themselves avoid becoming food for something else. Of Isle Royale's 120 or so species of summer birds, however, only about 20, joined by a few species from the Arctic, stay through the winter. These few birds and mammals are all that remains to enliven the elemental scene at this difficult time of year.

The conditions these animals must face vary from winter to winter, but always they are severe. Temperatures usually range between -25deg;F and +40deg;F. Frequent strong winds, generally from the west, add greatly to the chill of low temperatures. Snow depths range from one to three feet, with less under dense conifers and considerably more in drifts. Crust conditions within or on the snow sometimes help but more often hinder animals. Taken together, all these conditions make great demands on the energy of animals, at a time when food is in shortest supply.

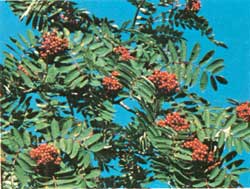

Over millenniums, northern wildlife has evolved various strategies for survival. Birds, with the power of flight, can go long distances to find food. In winters when birch seed is abundant, redpolls, pine siskins, and goldfinches may remain on the island in large numbers. In poor years they may wander in search of more productive areas. The same strategy is used by other northern finches, such as pine and evening grosbeaks, purple finches, and crossbills, depending on the supply of mountain-ash fruits, pine seeds, and other food. Birds that rely more on insect eggs and larvae—such as chickadees, blue and gray jays, and woodpeckers—have a more dependable source and consequently remain on the island in fairly stable numbers from one winter to another. Along the south shore, where the lake is usually open, a few mergansers and goldeneyes sometimes gather to feed on fish and other aquatic life. The ducks thus hunt in an environment that is usually considerably warmer than the air above. A few birds of prey, such as goshawks, horned owls, and in some years the snowy owls of the Arctic find enough birds and small mammals to tide them over.

The fruits of mountain-ash provide a reserve of winter food for many animals, including the red fox. (Photo by Wm. Dunmire) |

Plant-eating mammals, which are prey species, have developed highly individualistic methods for coping with winter and its predators. Deer mice and red squirrels lay up provisions during the long fall in numerous caches—in trees, logs or underground. Mice and squirrels store mostly seeds of various kinds, though squirrels may rely on fungi and birch and alder catkins in years when conifer seeds are scarce. For these little animals, the snow is a blessing, providing them with covered runways hidden from most predators and with insulation from the chill air above.

Beavers have a winter system of living that insulates them almost completely from atmospheric rigors and the danger of predators. Before ice forms, they cut branches of aspen, birch, and other favored foods and stick them into or weight them with stones on the bottom of their pond or lake, usually near the lodge. They plaster their lodge with a new layer of mud, leaves, and sticks. When winter's cold spreads a layer of ice over the water and freezes the mud on his house, the beaver is effectively sealed in, and winter and predators are sealed out. When he gets hungry, he leaves his lodge through an underwater entrance and visits the food cache. Occasionally, however, he may leave the confines of his home and pond to gnaw the bark from a tree felled in the fall. At such times he risks being caught by the wolf pack or perhaps by some half-starved lone wolf rejected by the pack and unable to kill moose.

Muskrats lead a much more hazardous life. They do not store food for the winter, and though they feed upon aquatic plants and some animals beneath the ice, they also venture out for land plants. While foraging, they are under threat from virtually every predator on Isle Royale—mink, otter, weasel, red fox, wolf, lynx, and large hawks and owls. Perhaps it is only his caution and unspecialized food tastes that allow any muskrat to survive the winter.

Cover is surely the prime winter concern of the snowshoe hare, for in most areas the supply of woody stems and twigs is adequate for his dietary needs. When winter strips away the deciduous leaves and green ground cover, the hare cannot safely wander as far as he did in summer. White-cedar swamps become headquarters for many hares, since they provide dense, low foliage that can also be eaten. On Isle Royale the hare's chief enemy is the red fox; the lynx, its principal predator through much of the north, is so rare here that it is hardly a threat; and the wolves concentrate on moose. Hares rely on their speed and their broad, snowshoe feet to escape foxes. If the snow is soft, foxes will sink in farther than hares during a chase, but if a crust has formed the chase is more even. Its change in winter to a camouflaging white coat also aids the hare in its struggle to survive.

For the red fox, winter is the critical season for survival on Isle Royale. |

And what about the moose, that huge beast that eats more and provides more food for predators and scavengers than any other animal on the island? Snow depth seems to be the moose's main concern, since it affects ease of travel. During winters with deep snow, moose concentrate near shorelines, where the abundant conifers intercept much of the falling snow and also provide browse. In these forests moose can also feed on twigs and bark of aspen, birch, and mountain-ash—among their favored foods. Frequent blowdowns put more food within reach. Deep, soft snow is more easily navigated by adult moose than by wolves, though calves are seriously hindered. A crust on or within the snow probably aids pursuing wolves. It seems, then, that food sources and snow depth regulate the moose's winter wandering, and that wolves are accepted as an environmental hazard. Healthy adult moose, in fact, seldom need to fear wolves; calves and infirm adults are the usual victims.

Predators, too, are faced by a reduced food supply in winter. Insects, reptiles, amphibians, and many binds have died, hibernated, or gone south. The young of various mammals are not as abundant as in summer, having been reduced by the many hazards of their environment. The remaining prey animals spend more time in dens. Most predators, therefore, are forced to hunt farther and longer for a meal. The island's few otters, for instance, must follow streams for miles, diving in where fast water keeps ice from forming, and searching for fish and crustaceans as far under the ice as their lungs will allow.

Redpolls and purple finches may remain on Isle Royale through the winter when the supply of birch and other favored seeds is good. (Photo by Durward L. Allen) |

In winter, red foxes depend heavily on hares; and, as we have seen, catching a hare in the snow is no easy job. In years of good mountain ash crops, foxes, as well as ravens and other wildlife, eat many clusters of the orange-red fruit. As we will see shortly, foxes are also inadvertently assisted through the winter by wolves.

Timber-wolf tracks follow the shore of Siskiwit Bay. (Photo by Jim Cole) |

The wolf's only real source of food in winter is the moose herd. Hares and smaller animals are hardly big enough to justify the energy expended in catching them, and beavers seldom venture ashore in that season. Possibly, wolves have an easier time finding and killing moose in winter than in any other season. Wolf packs hunt by following the easiest routes—usually on the wind swept ice along shorelines, but sometimes inland along previously used routes. The wolves trot along, usually in single file, until moose or fresh tracks are found. If a discovered moose stands its ground they usually soon leave, wary of the animal's dangerous hoofs. If the quarry runs, they chase it, single file. If deep snow, thick cover, or a long head start prevents them from catching up with the moose in a short time, they abandon the pursuit. But somehow they recognize weakness, and keep after infirm individuals. Attacking mainly the rump, they slow the animal down, eventually bring it to the ground, and then quickly kill it. Some victims, however, are merely wounded and left to weaken, and are killed later. After a kill, the wolves gorge, nest, then usually feed intermittently until the last bones are gnawed. A day or two after killing a calf, or several days after killing an adult, they are on the move again, seeking more fuel for their ever burning bodily furnaces.

The three scavenging ravens are members of a flock that follows the wolf pack. (Photo by Durward L. Allen) |

A kill has ecological importance that goes far beyond the survival of wolves. For when wolves leave a carcass, temporarily or permanently, other animals come for a share. Red foxes, particularly, congregate at a kill, for the moment forgetting their territorial animosities. Ravens, it seems, make most of their winter livelihood from wolves. They actually follow wolf packs on the daily rounds, picking some sustenance from feces left by the wolves, and waiting for them to make a kill, from which they later get a meal or two. Gray jays and blue jays, smaller cousins of the raven, also visit moose carcasses for scraps. Tiny chickadees pick at the bone marrow where the opening is too small for ravens or jays. Deer mice undoubtedly gnaw the bone marrow, and red squirrels may sometimes make use of the kill. Thus several kinds of animals ride through winter partly on the coattails of the wolf.

Just as fall is prolonged by the warming effects of Lake Superior, so spring is delayed by the water's slow adjustment to the temperature of the air above. The patches and solid sheets of ice that form on much of the lake are slow to break up. When they finally do, the cold water continues to cool the spring air masses flowing over the lake. The shore ice usually goes in April, although some years it persists until May. On May 3, 1972, when Ranger III made its first trip of the year, it had to break ice in Rock Harbor for several hours before it could reach Mott Island. That day, the snow lay 5 to 8 feet deep behind the National park headquarters building.

During May, tree leaves begin unfurling; skunk cabbage, hepatica, and other early flowers bloom; smelt and suckers swarm up streams to spawn; birds return en masse from the south. By mid-June, when the trees are usually fully leaved and many forest flowers are blooming, summer can finally be acknowledged.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Nov 4 2006 10:00:00 pm PST |