|

Volume XVIII - 1952

The Use Of The Wheeler Creek Pinnacles By Nesting Birds

By Donald S. Farner, Assistant Park Naturalist

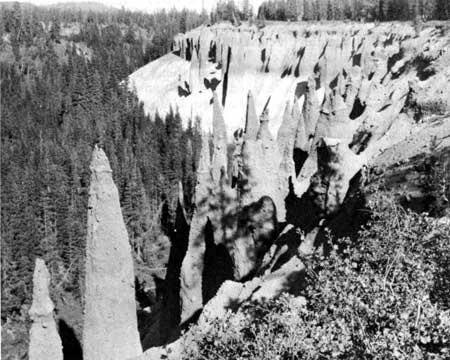

The Pinnacles of Sand Creek and Wheeler Creek have long been of

interest to geologists because of their contribution to our knowledge of

the pumice-scoria flows which descended the southern slope of Mount

Mazama prior to its collapse. These Pinnacles are the results of the

most intense fumarolic activity in the Park (Williams, 1942:8990). In

this activity pumice and scoria were hardened in vertical columns by

ascending gasses. The present form of the Pinnacles is the result of the

modification of these original columns by wind and water erosion. Some

of the Pinnacles are actually hollow and are sometimes referred to as

"fossil gas vents."

Curiously little attention has been given to the fact that the

pinnacles are of some ornithologic interest. Frequently they are used by

birds as song perches in the same manner as dead trees are used. Of even

greater interest, however, is the use of small cavities in some of the

Pinnacles as nesting cavities. There are at present records of the use

of such cavities by three species of birds. On June 26, 1952, I saw a

pair of Mountain Chickadees, Parus gambeli Ridgway, carrying

material into one of these cavities. Although I was unable to be

certain, it appeared that the material was items of food indicating that

the eggs had already been hatched. On the same day Park Naturalist Harry

C. Parker and I observed a pair of Mountain Bluebirds, Sialia

currucoides Bechstein, entering repeatedly an opening in one of the

Pinnacles. At the time, we could not feel certain that nesting activity

was in progress. However, on July 29 I saw a female enter the same

opening and on August 4, saw both male and female carrying insects into

the cavity. In the vicinity were two juvenile bluebirds apparently

completely independent of the adults. They were catching insects on the

wing. It would appear quite possible that these juvenile birds were from

the first brood with which the observations of June 26 could be

associated, whereas the food-carrying observed on August 4, was

doubtless in conjunction with the rearing of the second brood.

On July 19, 1952, I discovered a pair of Violet-green Swallows,

Tachycineta thalassina (Swainson), carrying food into a cavity in

the Wheeler Creek Pinnacles. The young could be seen and heard plainly.

Although Violet-green Swallows have been observed (Farner, 1952:74)

rather frequently in Wheeler Creek Canyon and elsewhere in the Park,

this is actually the first breeding record.

It should be noted that both the bluebirds and chickadees normally

nest in cavities in tree trunks. The Pinnacles thereby constitute a

curious, although understandable, substitute for tree trunks.

It is further of interest to note that Rough-winged Swallows,

Stelgidopteryx ruficollis (Vieillot), have also been known to

breed in Wheeler Creek Canyon (Farner, 1952:75). However, it appears

that holes in the cliffs, rather than holes in the Pinnacles, are

used.

References

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National

Park. University of Kansas Press. ix + 190 pp.

Williams, Howell 1942. The Geology of Crater Lake National Park,

Oregon. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 540. vi + 162

pp.

Nature Photography In Color In Crater Lake National Park

By Ralph Welles, Ranger-Naturalist

In nature photography it is axiomatic that you must take the picture

when you see it, because it may not be there the next time you look.

This implies the necessity of special equipment and a special

willingness to go to work at any time, because wild life has a time

clock of its own.

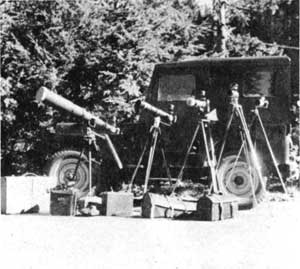

Photographic equipment used by Ranger-Naturalist Welles

and Mrs. Welles during the summer of 1952.

I recall the particularly colorful yellow-bellied marmot that used

to sit in the late afternoon on a rock in the meadow back of

headquarters. We never saw him except in the late afternoon when the

light was almost gone. I had watched for him there several times during

the day but he never put in an appearance, so I finally realized that I

would have to get him on his own terms and took his picture that evening

about six o'clock. The next morning a marmot was found dead on the

highway in the same vicinity, and while it may be merely coincidence, a

particularly colorful marmot never appeared on that rock in the meadow

again.

It is our belief that wild life should be photographed in the field

as much as possible under natural conditions and natural light and

natural habitat. In order to do this, Mrs. Welles and I carry with us

most of the time a jeep-load of cameras, lenses, tripods, and

miscellaneous equipment. This includes four Leicas, a Kodak Bantam, and

lenses ranging in focal length from 35 mm to 640 mm. At all times we

keep three Leicas mounted on telephoto lenses - a 300 mm, the 500 mm,

and the 640 mm - with direct viewing repriscopes, each with its own

special tripod. This leaves one Leica free for the interchangeable use

of the 35 mm, the two 55 mm, the 85 mm and the 150 mm lenses for scenic,

habitat shots and so forth. We employ flash guns, Strobe light and

restrictive handling only when it appears impossible to get a picture

any other way. For instance, a bat must be either held in the sunlight

or taken with a flash because of his light shunning habits.

Photographically speaking, the 1952 season at Crater Lake National Park

was highlighted by the discovery and the subsequent coverage of a den of

Cascade red foxes, a nest of bald eagles and the habitat of a great gray

owl.

The red foxes were first reported to me on July 7th by Assistant

Chief Ranger Packard, who went with me that afternoon to their den about

half a mile beyond the Rim Village off the north road. After searching

the area for about half an hour and finding no evidence of foxes, we

decided we must be in the wrong location, and turned to go. As is so

often the case, we found that although we had not seen it, we had been

under observation by one of the young foxes for some time. He was

sitting on the ridge about thirty feet away, apparently as curious about

us as we were about him.

A very yound golden mantled ground squirrel taking what

is perhaps his first bite of rotten wood. From a kodochrome by

Ranger-Naturalist Ralph Welles and Florence Welles.

I got one shot of him with the 500 mm, and with the click of the

shutter he vanished back of the ridge. We saw no more of him that day,

but during the following two weeks my wife and I had the opportunity of

observing the entire fox family and photographing them around their

various dens as they moved farther and farther away from human

interference. The three young ones became for a time almost indifferent

to our presence, because, as is well known, the parent foxes have a

great deal of difficulty in teaching their young to be afraid. We

eventually were able to photograph all three of the young almost at

will, but were able to get only distant shots of the wary adults. In

this connection it is of interest to note that whereas most male

carnivores will eat their young if given the opportunity, the male red

fox helps take care of the young until they are able to take care of

themselves.

The last time we visited their den, on July the 23rd, we saw no sign

of the young foxes, nor did we hear the peculiarly eerie wild barking of

the parents in the deep hemlock forest below the ridge.

In the meantime, on July 18th, former Superintendent E. P. Leavitt

told us about a bald eagle's nest at Diamond Lake, and we went with him

immediately to locate it. He had only visited the locality once and then

by boat from Diamond Lake Lodge, and as the lake was too rough to take a

boat out that day, we drove around to the near vicinity, but could not

identify the nest.

Returning two days later, we inquired at the fish hatchery whether

anyone knew where the eagle's nest was, and were promptly offered a boat

ride across the lake by Jay Hoover of the Fish and Game, who knew where

it was, and who landed us on the marshy shore about a hundred yards from

the one hundred fifty foot fir in the top of which could be plainly seen

the clutter of sticks we were looking for. For a half an hour or so

there was no sign of life in the dense forest in which we found

ourselves except for the clouds of mosquitoes which seemed to be

impervious to the insect repellent we had with us.

Looking almost directly up at the nest we could see no young in it

and the adults were apparently out over the lake at the time, so we

occupied ourselves with a close-up telephoto shot of the nest to show

its construction, and also general habitat shots.

While so doing we suddenly heard at some distance through the trees

the weird, loud cacaphony of the adult eagle's cry of alarm. Moving in

that direction we almost immediately came upon an extremely exciting

spectacle. Close together in the high top of a dead Douglas fir, with

white heads and tails gleaming in the sun were two great bald eagles. We

were able to get two good shots of them before either their excitement

or ours caused them suddenly to soar away out of sight.

Two-year old bald eagle. From a kodachrome by

Ranger-Naturalist Ralph Welles and Florence Welles.

Later that afternoon we made two discoveries that facilitated

observation and picture-taking of our quarry. There was a narrow opening

in the forest through which the nest could be seen from the road, and

secondly, by climbing the mountain on the other side of the road about

fifty yards we found that we could observe not only the nest but that

there were two very young but not small nor "baldheaded" eagles in it.

Although it was to be several weeks before "the babies" could fly, they

were already nearly as large as their parents and their heads were still

as dark as the rest of them as they would continue to be for three or

four years.

From our view-point on the mountain we set up our 500 mm and 640 mm

cameras and waited. It was two hours before we had the gratification of

seeing and photographing a parent eagle swoop down with breath- taking

swiftness and alight on the edge of the six-foot nest and proceed to

tear up what appeared to be a large white bird and feed it to the

young.

We saw them at weekly intervals up until the time of this writing.

When last we observed them one of the adults was no longer putting in an

appearance, the young were learning to fly, stretching and flapping

their great wings (they already had a wing-spread of approximately six

feet), sometimes rising two or three feet, then settling back down.

A more complete record of our experience with the great gray owl is

contained elsewhere in this issue of Nature Notes.

It would be easy, not to say delightful, to spend an entire summer

photographing the golden mantled ground squirrel, the Olympic black bear

or the Clark nutcracker. A book could be written about how we came into

possession of a great horned owl which we eventually banded (with the

help of Ranger-Naturalist Wally Ernst, who was of invaluable aid to us

on that and many other occasions) and turned loose on Dutton Ridge. I

could write about the courage and tenacity for life of the badger that

we found stunned and bleeding on the road where he had been struck by a

passing vehicle.

You can see pictures of these and many others and hear their story

when you attend the Naturalist talks at Crater Lake National Park.

|