|

Volume XVIII - 1952

The 1952 Invasion Of California Tortoise Shell Butterflies

By Donald S. Farner, Assistant Park Naturalist

At irregular intervals Crater Lake National Park is visited by huge

numbers of Tortoise Shell Butterflies, Aglais californica Bdv.

Previous invasions have been described by Scullen (1930), Constance

(1931), and Lowrie (1951). Doubtless others have occurred without being

recorded. The chronology of the 1952 invasion was very similar to that

of 1951. The butterflies first began to appear about July 30 and seemed

to reach their maximum abundance during the first week in August when

prodigious numbers were to be observed in flight and resting on

buildings. They were observed in abundance at the summits of Mt. Scott,

the Watchman, and Dutton Cliff.

Doubtless these butterflies constitute an abundant source of food

for several species of animals. During the last week of July and the

first week of August there was a pronounced increase in the numbers of

Clark's Nutcrackers, Nucifraga columbiana (Wilson), along the Rim

Highway. On several occasions I have noted them feeding on the

California Tortoise Shells which had been killed by automobiles. The

same observation has been made by Ranger-Naturalist R. M. Brown. On

August 10, Ranger Naturalist C. Warren Fairbanks saw three ravens,

Corvus corax Linnaeus, feeding on these butterflies on the

highway near Llao Rock. He also found six in the stomach of a Rainbow

Trout, Salmo gairdnerii Richardson, caught near Eagle Cove on

August 17. Ranger-Naturalist Brown also observed a Golden-Mantled Ground

Squirrel, Citteilus lateralis (Say), taking one on August 7 near

Hillman Peak. These ground squirrels were frequently observed to take

butterflies which dropped from the radiators of automobiles at the

checking stations. The use of butterflies as food by the Golden-Mantled

Ground Squirrel, however, is apparently not unusual (Gordon

1943:27).

References

Constance, L. 1931. A butterfly pilgrimage. Nature Notes from

Crater Lake, 4(2):3-4.

Gordon, Kenneth. 1943. The natural history and behavior of the

Western Chipmunk and the Mantled Ground Squirrel. Oregon State

Monographs, Studies in Zoology, No. 5. 104 pp.

Lowrie, Donald C. 1951. Butterflies of Crater Lake National Park.

Crater Lake Nature Notes, 17:10-11.

Scullen, H. A. 1930. The California Tortoise Shell Butterfly.

Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 3(3):2.

The Mazama Newt: A Unique Salamander Of Crater Lake

By James Kezer, Ranger-Naturalist

and Donald S. Farner, Assistant Park Naturalist

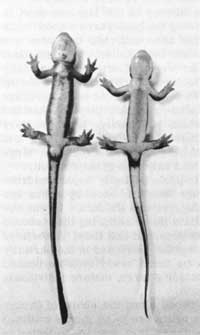

Under-surfaces of two closely related newts. A Mazama

newt from Crater Lake at the left and a common Oregon newt on the

right.

|

During the past two seasons many of the visitors to Crater Lake

National Park have been able to get some first hand contact with one of

the most distinctive and interesting animals of the Lake. This is a

salamander or water-dog, oftentimes called the Mazama newt or Crater

Lake newt; it is found no place in the world outside of the waters of

Crater Lake. Believing that many of the visitors to the Park would be

interested in this unusual animal, we have frequently exhibited living

specimens during lectures in the lodge and the community building and

the excitement that is invariably caused by the circulation of the jars

of newts has indicated to us that these salamanders are indeed a real

source of interest to our visitors. If one compares the Mazama newt

(Triturus granulosus mazamae) with the common Oregon newt

(Triturus granulosus granulosus) it is clearly evident that the

two are very closely related. Indeed, the difference between the two is

simply a matter of the pigmentation of the lower surface; the immaculate

orange-yellow of the Oregon newt is replaced in the Mazama newt with

varying amounts of dark pigment that appears to invade the under surface

of the animal from the sides. This difference in pigmentation is

illustrated in the photograph in which the under surfaces of the two

kinds of newts are shown. It should be pointed out that the amount of

black pigment on the lower surface of a Mazama newt is highly variable;

some individuals have lots of it and others approach closely the

pigmentation of the common Oregon newt.

Our best interpretation of the Crater Lake newt population assumes

that hundreds of years ago some common Oregon newts were able to get

into the Lake through an unknown route, probably during a period when

the climate was much wetter. The steep, dry walls of the Lake Rim have

apparently served as an isolating mechanism, allowing the Crater Lake

newts to develop a different genetic composition and resulting in the

pigmentation differences that now separate this group of water-dogs from

the common Oregon newt. It is a very interesting fact that a specimen of

the common Oregon newt collected within the Park boundaries as close as

two and one-half miles from the Lake showed none of the under-surface

black of a Mazama newt. This is surely a tribute to the isolating

function of the caldera walls.

Our present knowledge of the life history of the Mazama newt is

fragmentary, despite the fact that during the past years a good many

members of the ranger-naturalist staff have searched the water and the

shoreline of Crater Lake for such information. The smallest larvae that

we have found in the Lake were collected in a partially cut-off pool

behind the Government Boathouse on Wizard Island during the first week

of September, 1951. Ten of these larvae had an average length of about

3/4 inch which indicated to us that they had hatched from the egg mass

at least three weeks previously. It seems very probable that the eggs

from which these larvae came had been laid during the summer, perhaps

back in the spaces between the large blocks of lava where they would be

found only with great difficulty.

In the water along the shore and in pools partially separated from

the Lake, large larvae with an average length of about 3-1/4 inches are

commonly found. Our limited data suggest that the small larvae observed

in the pool on Wizard Island attain this size during their second season

of growth, undergoing metamorphosis at that time. Associated with the

large larvae in the water along the shore and in the partially cut-off

pools on Wizard Island, may be found newly metamorphosed newts and

adults of various sizes, including large, mature individuals averaging

about 6-3/4 inches in total length.

If one lifts up the rocks and driftwood along the shore of Crater

Lake he soon learns that the Mazama newts are by no means confined to

the actual water of the Lake. Oftentimes they may be collected in large

numbers under the debris along the shore, frequently in association with

the long-toed salamander, Ambystoma macrodactylum. In this

non-aquatic environment they appear desiccated and sluggish with

extremely granular skins. We have considered the possibility that these

semi-terrestrial individuals represent a definite stage in the life

history of this newt; however, since no single age group is involved, it

seems more probable that a transitory semi-terrestrial existence

represents an aspect of the behavior of the Mazama newt at various times

during its life.

On several different occasions we have observed large aggregations

of the Mazama newt along the shore of the Lake. Usually these

aggregations consist of semi-terrestrial individuals in groups of about

twelve to fifteen out of the water and under rocks or pieces of

driftwood. A somewhat different kind of aggregation was observed

September 6, 1951, on the east side of Eagle Point where the shore of

the Lake consists of a rocky beach covered with willows. Two hundred and

fifty-nine newts were massed together in an area of water not more than

thirty feet square, the vast majority of these being under a single flat

rock about nine feet square, resting on other rocks in approximately one

foot of water. Making up the aggregation were adults of varying sizes,

large larvae and newly metamorphosed individuals.

On August 7, 1952, an enormous aggregation of Mazama newts was

observed under rocks in the shallow water of about 15-20 feet of

shoreline in Eagle Cove. We estimated that at least three hundred newts

were involved in this aggregation and, as previously noted, all sizes

from large larvae to the largest adults were present. At this time the

significance of these aggregations is not understood.

From the zoological standpoint, the newts of Crater Lake are

particularly interesting because they provide material for the

determination of the time required for the genetical change that is

necessary for the development of a subspecies. The collapse of Mt.

Mazama has been accurately established by modern techniques as occurring

between six and seven thousand years ago. This information clearly

indicates that newts could not have entered the water of Crater Lake

more than about six thousand years ago; moreover, considering the

subsequent eruptions that brought about the formation of Wizard Island,

it is highly probable that the Lake newt population was established much

more recently. Indeed, the Mazama newts are doubtless one of the most

clearly dated cases of subspeciation available any place in the

world.

|