|

Volume XXXI - 2000

Why So Many Siskiyou Plants?

By John Roth

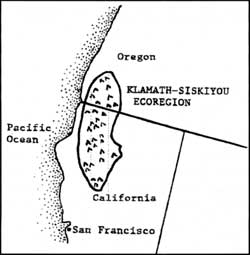

The Klamath-Siskiyou Ecoregion, hereafter KSE, is an oblong area that

extends from Roseburg in southwestern Oregon to the Yolla Bully range in

northwestern California. The varied geology, location, and microclimates

of the KSE accelerated plant evolution and migration but slowed

extinction. At least 3,000 types of plants and all the major forest

types in western North America occur here. More than 200 of these plants

are KSE endemics, the name for a species found only in a particular

area. Oregon Caves National Monument, as a small but important zone of

transition in the KSE, illustrates this floral diversity by boasting

almost one plant species per acre.1

Geologic controls

Ocean basins were spread apart or squeezed for more than half a

billion years while molten magma crystallized into rocks as different as

basalt and granite. Erosion and metamorphism created another range of

strata as well: sandstone, marble, pebbly conglomerate, glacial silt,

and "baked" muds. Faults uplifted and split rock masses apart, changing

what once were islands and ocean basins into a complex rock mosaic. This

fragmentation of habitat favors small populations on each type of soil

or rock, a situation in which mutations that give rise to new species

are not diluted out of existence by interbreeding with large

populations.

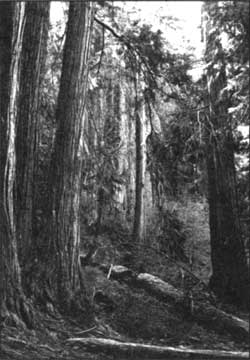

A stand of Port Orford-Cedar near Oregon

Caves.

|

Peridotites are rocks with potent quantities of minerals like iron

and magnesium that change to metal-rich serpentine when hot water is

added. Since most life is not adapted to metals normally found deep in

the earth, these metals disrupt photosynthesis and inhibit microbes. The

most toxic may be nickel, chromium, and cobalt though plant distribution

in the KSE seems to be governed by the occurrence of magnesium. Little

soil forms because clays need aluminum, an element lacking in

serpentine. This and the toxicity of metals in serpentine will not allow

clay, organics, or soil clumps to hold water, The cycle snowballs and

becomes a situation where thin soils are often dry, hot, and

nutrient-poor. This provides open habitat, increases population

turnover, and thus encourages the evolution of new species. Because

their populations are smaller, species that are rare usually evolve

faster than common and/or widespread plants. Of the 200 endemic plant

types in the KSE, 141 are either rare or uncommon, a very high ratio for

endemics.

The low productivity of serpentine soils limits the dispersal of

endemics to new areas because of fewer pollen grains, seeds, or tall

plants. Seeds in serpentine tend to be larger because of being in such

stressful habitat, so as to give seedlings a head start on life. This

characteristic may also limit dispersal, thus increasing the number of

endemics.

The most common response for most plants on serpentine is to keep

nickel out of their cells. Even some mariposa lillies and wild

buckwheats living on non-serpentine soils tolerate high amounts of

normally toxic metals, so they appear better prepared for evolving new

species on serpentine soils, Some KSE plants have found other ways to

avoid serpentine toxicity. In an endemic pennycress mustard and jewel

flower, the plant stores nickel within its cell tissue. Another jewel

flower (Streptanthus tortuosus) has developed a race of

serpentine-tolerant plants and so may be on its way to becoming a new

species.

Rapid evolution is also indicated by the fact that roughly two-thirds

of KSE endemics are varieties or subspecies that likely are on their way

to becoming full species. The crowding of habitats in the KSE results in

many hybrids, some of which have given rise to new species.

An avenue for plant migration

Imperial Lewisia. Drawing by Heather McDonald.

|

The KSE is unusual in that it has more serpentine than any other

ecoregion. The serpentine masses and size of the KSE helps plant

migrants find suitable habitats more easily but are big enough to keep

extinction rates low. Serpentine in the Illinois Valley, for example, is

fragmented and possesses different chemistries—an ideal situation

for rapidly evolving small populations. The effects of fire or other

disturbances may be so long lasting that plant populations are separated

sufficiently and can evolve into new species. By the same token,

disturbances in the KSE are not so large and competition among plants is

not intense enough for extinction rates to increase. Varied rainfall

amounts, frequent burns, and areas that serve as barriers (riparian

zones, serpentine, cliffs, north slopes) tend to limit fires to patches

of moderate size and intensity. Consequently, no one successional stage

dominates with its restricted number of species.

Another reason for the relatively high species diversity in the KSE

is because it contains the only mountains linking coastal ranges in

California and Oregon with the Cascade-Sierra cordillera. Plants more

easily cross over east-west oriented mountains, unlike north-south

ranges where plants must migrate along lines of longitude if they cannot

cross high elevations. Migration can promote speciation because it

produces numerous small and isolated populations near the range limit of

a species, a situation common in the KSE. Proximity to the endemic-rich

Cascades, Sierra, and the coast ranges of northern California has

increased plant diversity as the KSE shares over 200 endemics with these

physiographic regions. At least half of those plants probably originated

in the KSE.

Vollmers Tiger Lilly. Drawing by Heather

McDonald.

|

Extinction is low among shrubs and trees generally, furnishing an

important reason why they comprise many of the paleoendemics, or "living

fossils." If you live a long time, you have more chance of reproducing

at least once successfully. Even serpentine herbs tend to be long-lived,

a trait indicative of harsh environments, and one the likely increases

the number of endemics. During the great climate changes over the last

few million years, the closely packed habitats of the KSE allowed plants

to grow in adjacent habitats that increased the chances for survival

when the climatic regimes shifted. Some habitats shrank considerably,

but paleoendemics in them continued to thrive. Port Orford-cedar and

Brewer (or weeping) spruce are examples of paleoendemics that once had

more extensive ranges.

Another type of endemic commonly found in the KSE is the edaphic

endemic or geoendemics—those species mostly restricted to one soil

type or topographic situation. Neoendemics (plants with no nearby

relatives) in the KSE also appear to be more common near the north end

of their range at high elevations, perhaps because they are also glacial

relicts that found suitable cool and open habitats to colonize. Among

the endemic plants in the KSE, 80 types are found only on serpentine,

while seven are confined to granite, four on marble, and three on

volcanic rock.

Other factors promoting diversity

A lack of nutrients and water (up to a point) encourage greater

diversity because plants then spend more of their energy surviving such

conditions rather than competing with other plants and causing them to

become extinct. The leaching of soil nutrients through high temperatures

and rainfall lowers the productivity of soils and may increase the

diversity of herb. Since the KSE is characterized by low rainfall during

the growing season for herbs, habitat diversity is heightened because

there are marked differences in slope and aspect that control

evapotranspiration and the water retention capacity of soils.

More nutrients and water allow certain plants to dominate and thus

reduce plant diversity, the so-called paradox of enrichment. The KSE is

an area of climatic extremes, with annual rainfall amounts ranging from

100 inches near the ocean to 15 inches further inland. The differences

in rainfall gives rise to a patchy distribution of plants, with the many

subspecies and varieties of certain plants indicate rapid

speciation—especially in their adaptation to dry soils of

serpentine, marble, and granite. For example, dwarf ocean spray, myrtle,

buckthorn, and tanoak stay small in stature even if grown in gardens

with lots of water. Drought adaptations in endemic plant species include

large tubers (as in lillies and toothworts), woodiness (as in pussytoes

and pincushion), and waxy, hairy or divided leaves. Storing carbon

dioxide at night so that water is not lost through leaf pores by day has

favored many endemic sedums and lewisias.

The varied habitats and climate change over thousands or millions of

years resulted in 50 or more disjunct species, plants whose brothers or

population centers are hundreds of miles distant. Mutations are favored

in such situations because of their small populations and the need for

new adaptations to survive in a less than ideal habitat. The KSE also

hosts at least 100 plant species at the edge of their range, where

speciation most likely occurs due to isolated populations undergoing

rapid change. Being at the right location between northern and southern

plant communities, the KSE is situated so as to have a high number of

disjunct species as well as plants at their geographic limit.

As a refuge for plants that once ranged from Japan to Georgia, the

KSE provides rare habitat in the western United States. Many of the

plant relicts are members of old families: heathers, orchids,

honeysuckles, birthworts, and lillies. Plants such as fairybells,

woodland stars, dogwoods, rhododendrons, redwoods, trilliums,

gaultheria, and coralroots have their greatest diversity of species in

the northwest and southeast United States, as well as in eastern Asia.

Paleoendemics evolved once tectonic forces and climate changes cut the

connections to other landmasses. Trees such as Port Orford-cedar and

Baker cypress, for example, have "twin" species in Asia. Likewise,

cousins of plants in the KSE such as vanilla leaf, tanoak, Oregon grape,

redwood, and skunk cabbage grow in eastern Asia.

Conclusion

California Lady Slipper. Drawing by Heather

McDonald.

|

The KSE enjoys the best of diversity among plants; it contains older

flat areas where the lack of major disturbances has allowed

paleoendemics to survive, but also provides newer habitats like cliffs

and cirque lakes where new species can evolve due to isolation and a

lack of competition. Northern Florida may possess more paleoendemics and

Hawaii has greater numbers of neoendemics than the KSE. Parts of Nevada

and Arizona display more edaphic endemics, but the distinctiveness of

the KSE lies in its mix of all three types of endemic plants—more

profuse than anywhere north of Mexico. In few other places will the

location, size, varying ages and geodiversity of mountains with their

varied climates combine to produce so many relicts, disjuncts, endemics,

varieties, hybrids, and plants near their geographic limit. The Illinois

Valley is a botanist's delight each spring, while Oregon Caves

constitutes a representative slice of the fascinating floral diversity

found throughout the KSE.

Note

1The monument list contains some 400 plant species in only

480 acres, whereas Crater Lake National Park boasts fewer than 700 in

183,220 acres.

John Roth became fascinated with the plants of southwestern

Oregon upon arriving at Oregon Caves National Monument in 1988.

|