|

By Edwin D. McKee, Park Naturalist IN NORTHERN ARIZONA where dwell the Hopi Indians of ancient lineage, famed for their pottery and other arts, and where live the semi-nomadic Navahos, noted for their silver work and basket weaving, attention is seldom given to the enterprises of the Havasupai Indians - people far less picturesque yet capable of producing some of the most thoroughly artistic basket work found anywhere in the region. The Havasupai Indians (people of the blue-green waters) live today in the bottom of Havasu Canyon which joins Grand Canyon on the south some thirty miles west of Grand Canyon village. They were living there when the first white explorers came into the region, although they once ranged over considerable additional territory and some of them had homes at what is now known as Indian Gardens. Apparently the art of basket-making dates back a long way with the Havasupai since their baskets largely take the place of pottery as water containers, burden carriers, and storage bins. The only ceramic utensils which they make are crude, undecorated types of jars used in cooking, although they obtain some pottery from the Hopi for other uses. Havasupai baskets are of six types according to Spier.1 These are burden baskets, water bottles, shallow bowls or trays in twine and in coil, stone-boiling bowls and parching trays. The first two and the last mentioned types are always made with twine weave. The others are made sometimes in twine, sometimes with a coiled technique.

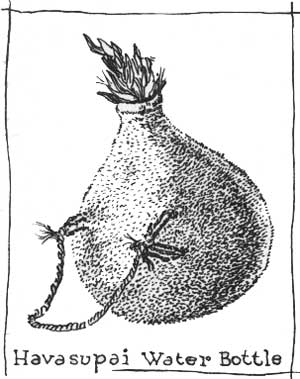

The burden baskets of the Havasupai are large and conical with occasionally a projecting bulge at the apex. They are woven of coarse but strong fibers of cat's claw, willow, or cottonwood. Formerly two loops made of horsehair were secured to the upper part of the basket to hold a yucca carrying strap. Today both the loops and the strap are usually made of one piece of leather, sufficiently wide in the center to rest conveniently against the forehead of the woman using the basket. (See cover). Water bottles are also made with a coarse weave and all of those seen by the writer have been very assymmetrical and irregular in shape. Some have conical bottoms, but a majority seem to be flat or even inversely cone-shaped. The necks are necessarily narrow, and are usually stoppered with leaves. Two handles of horsehair or yucca are fastened just above the widest part and the surface is covered with a coating of pitch from the Pinyon Pine to make it impervious. The real artistry of the Havasupai woman is seen in her trays and bowls. These are usually made of the split twigs of cat's claw, Acacia greggii, decorated with the black outer layer of the seedpod of the devil's claw, Martynia sp. In shape they vary from round or oval plaques, nearly flat but with slightly upturned margins, to baskets of bowl or cylindrical proportions. Apparently there is no type form or forms for practically every one of some dozens examined by the writer was unique in this respect. The amount of curvature, the height of the rim and the general shape showed remarkable diversity, though nearly all these baskets were symmetrical and well made. Because of the interesting variety of types, of the real beauty obtained in many of the designs and of the comparative rarity of the baskets as a whole, the writer has, during the past few years, made a collection of Havasupai baskets, keeping a record in each case of the maker and date and obtaining other data when possible. The collection now numbers fifty specimens and includes some of exceptional quality and interest, thus prompting the brief discussion of design that follows.

Spier2 records that "--there is very little attempt at design composition and diverse units are crowded on the same basket without regard for their appropriateness--". This is probably true in the work of certain individuals, especially in baskets made for tourist sale. Certainly the workmanship and the artistic temperament of some of the women are infinitely inferior to those of others. Such designs as shown in the accompanying drawings, however, most assuredly demonstrate a real sense of art and beauty as well as careful thought. Elsie Sinyella says that it is customary to fully plan a pattern in advance. Sometimes, of course, the original idea is not entirely carried out,as shown in one of her baskets on which she points out that butterflies were planned but discontinued after the making of only one wing in each case. Mac Putesoy's wife says, "I plan ahead but do not always know what entire design will look like in the end." According to Gus Walema the women "draw the designs in their heads" before making them. It appears evident, therefore, that even in cases where parts of the designs are copies, the Havasupais plan the arrangement in advance.

Among the Havasupai women now making baskets, the work of Nina Siyuja and Fay Marshall is outstanding. Elsie Sinyella, Lina Iditicava, Eunice Paya, Lily Burro, Dottie and Elva Watahomigie, and Edith Putesoy also demonstrate ability combined with an artistic sense. No doubt there are others who make good baskets, but with whose work the writer is not acquainted. The designs used commonly today are of animals and of

geometrical figures often centering around six-pointed stars. After

talking with several Havasupai women on the subject, the writer is

fairly convinced that Spier3 was correct in saying, "Designs do not

represent objects, and in fact, the women repudiate the idea that any

meaning might be read into them, There are no recognized design units

nor design names: the women did not seem inclined to speculate about

them." The designs are merely ornaments -- in many cases extremely

artistic. Elsie Sinyella indicated an eagle on a basket and said that it

was "Indian" (Havasupai), a duck which she said was from a picture, and

a geometrical design which she attributed to "Navaho rug". Apparently

many ideas are from the latter source. Another symbol,

Essentially all of the Havasupai decorations are black on a white background, as already stated, however, the reverse is found in a basket made by Dottie Watahomigie in which the black devil's claw is used as the background and the design appears in white. In only two instances has the writer seen Havasupai baskets including any color. These were both of crude workmanship and were obviously for tourist trade. One used a bright red annalin dye and the other a strip of orange.

The time required in making a basket can scarcely be estimated. Asked concerning this matter, the Havasupai women almost invariably reply that they do not know. This is no doubt largely due to the fact that work is done during very irregular and scattered periods, so actually they do not know the total time spent. Gus Walema's wife, Irene, estimated about three months to complete a basket of fine weave and medium size. This, however, probably meant with work done only "now and then" as is usually the case. She added that in former years plaques and baskets were used as plates and dishes but that today the tin and china ware of white man has replaced the basketry for such uses.

| ||||||

| <<< Previous | > Cover < | Next >>> |

vol8-1c.htm

14-Oct-2011