|

HAWAI'I VOLCANOES & HALEAKALA Volcanoes of the National Parks of Hawaii |

|

GEOLOGIC SETTING

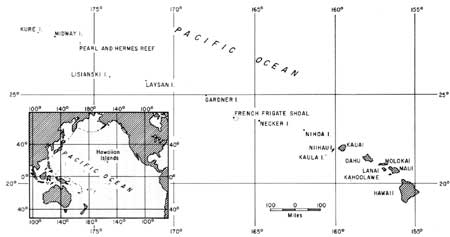

Fifteen hundred miles across the central Pacific stretches the line of islands that we call the Hawaiian Archipelago (see Figure 1). Most of the larger islands are well watered and clothed in tropical vegetation — green jewels set in a band of sparkling white surf, and laid in the blue plush of the ocean. The small islands northwest of Niihau — the so-called Leeward Islands — are too small to collect a toll of moisture from the passing winds. They are barren and waterless. Lanai and Kahoolawe also are dry, because the high islands to windward of them extract the water from the wind before it reaches them.

Tiny dots upon a map of the Pacific, the Hawaiian Islands are in reality the tops of a range of mighty mountains, perhaps the greatest mountain range on earth, built up from the sea floor by thousands upon thousands of volcanic eruptions. The average depth of the floor of the ocean on the two sides of the island chain is about 15,000 feet. Thus the lowest of the islands are mountains more than 15,000 feet high; and Mauna Kea, on the island of Hawaii, rises some 30,000 feet above its base. It is the highest peak in the islands, and quite probably is the world's highest mountain in terms of elevation above its base.

The Hawaiian mountains were born when a fissure opened in a northwest-southeast direction across the floor of the Pacific Ocean. How long ago this happened we have no way of knowing. The oldest rocks of the major islands now visible above sea level date from the late Tertiary period of geological time, some 5 to 7 million years ago.

Through most of the period of the islands' growth upward through the ocean water the building force of volcanism met little opposition. But as the top of the mountain reached into shallower water near the surface of the sea first currents and then waves began to attack the growing mass, knocking fragments of lava rock loose and washing them away into deeper water. When eventually the volcanoes thrust their heads above the sea their struggle for existence became still more intense. Then began the great battle between the constructive forces of volcanism, ever striving to build the island upward and outward with flow upon flow of new lava, and the destructive forces of wave, stream, wind, and even ice erosion, carving away the land and carting away the debris to dump it into the ever-hungry abysses of the ocean. So long as volcanism continued fully active the islands continued to grow, but when volcanic activity weakened and finally died out the powers of erosion seized control. Great canyons were carved into the slopes by streams, waves battered away at the shores, cutting them back into high cliffs with broad shallowly submerged platforms at their bases, and the whole land mass was gradually worn away. The ultimate end of this process is a broad, nearly flat platform cutting across the volcanic cone a few tens of fathoms below sea level. All that is left of the former islands is a shoal.

FIGURE 1. Map of the Hawaiian Archipelago, showing the

location of the major islands. The small inset map shows the position

of the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific Ocean. (click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

Before this final stage of erosion is reached, however, a new agent of construction appears. On the shallowly submerged platforms, organisms such as corals start to grow in abundance, and secrete their limy skeletons to form reefs. In their early stages these reefs surround a central volcanic island, and are known as fringing reefs. In later stages the volcanic island may disappear entirely leaving only a limestone reef, slightly submerged to form a shoal, or projecting slightly above the water to form an island. Such "coral" islands are ring-shaped and are known as atolls.

Volcanism appears to have progressed southeastward along the great fissure in the ocean floor. At least, the volcanoes at the northwestern end of the Hawaiian chain ceased activity long before those at the southeastern end. The northwesternmost volcanic mountains have been eroded away until no more volcanic rock can be seen. The visible parts of Kure and Midway Islands are formed entirely of organic limestone and calcareous sand, the remains of lime-secreting sea animals and plants, but at a depth of only a few hundred feet the limestone rests on the truncated summits of great volcanic mountains. At French Frigate Shoal, La Perouse Rock is a tiny remaining pinnacle of volcanic rock projecting through the limy reefs. Necker and Nihoa Islands are remains of once much larger volcanic islands, and Niihau has lost a great slice of its eastern slope through marine erosion. Kauai and Oahu Islands were deeply eroded by streams and waves before a renewal of volcanic activity buried much of their lowlands beneath floods of late lavas. On Maui, the volcanic mountain comprising the western part of the island has been deeply dissected by streams, with the formation of huge valleys such as Iao. Haleakala Volcano, forming the eastern part of Maui, also had great valleys cut into it by stream erosion before renewed volcanism partly buried the work of the streams.

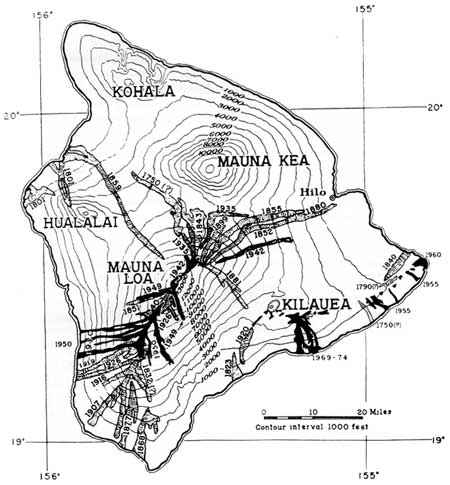

Hawaii is the southernmost and largest of the islands and also the youngest. Of the five great volcanoes (Figure 2) that built this largest of deep-sea islands, Kohala Volcano at the northern end of the island is the oldest. Streams have cut huge spectacular canyons into its rainy northeastern slope, and waves driven by the nearly constant trade winds have cut high cliffs along its northeastern shore. Next to the south, Mauna Kea erupted last about 4,500 years ago. During the last great period of glaciation, up until perhaps 15,000 years ago, its summit was covered by a small glacier. Hualalai, on the western part of the island, has erupted once in historic time, in 1801. The two southernmost volcanoes, Mauna Loa and Kilauea, have been active frequently throughout historic time, and for the most part are almost unmarred by erosion.

FIGURE 2. Map of the island of Hawaii, showing the location of

the principal volcanic mountains and the historic lava flows. (click on

image for an enlargement in a new window)