|

HAWAI'I VOLCANOES & HALEAKALA Volcanoes of the National Parks of Hawaii |

|

MAUNA LOA, FIERY COLOSSUS OF THE PACIFIC

Description. Mauna Loa is the world's largest active volcano and probably the largest single mountain of any sort on earth. It rises 13,680 feet above sea level, and approximately 30,000 feet above its base at the ocean floor. Its volume is of the order of 10,000 cubic miles, as compared to 80 cubic miles for the big cone of Mount Shasta in California. This huge bulk has been built almost entirely by the accumulation of thousands of thin flows of lava, the individual flows averaging only about 10 feet in thickness.

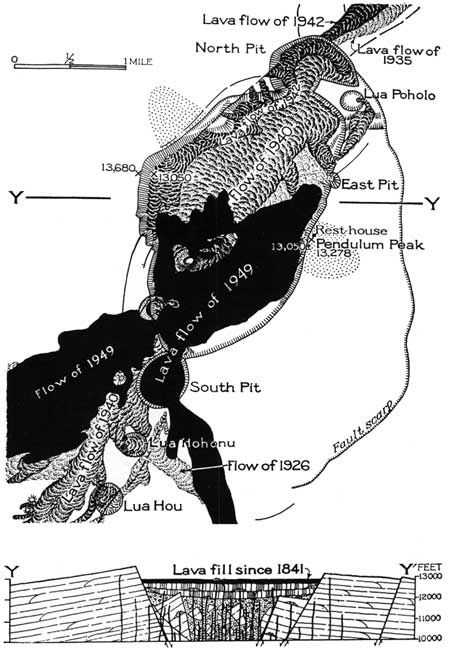

In form, Mauna Loa is a very broad flat dome, the slopes of which nowhere are steeper than about 12°. Similar slopes extend outward beneath the water all the way to the sea floor. This type of volcano is known as a shield volcano. At the summit of Mauna Loa is an oval depression 3 miles long, 1.5 miles wide, and as much as 600 feet deep. This depression, commonly called "the crater" but more properly termed a caldera, was formed by insinking of the summit of the mountain. Its name is Mokuaweoweo. At the northern and southern ends Mokuaweoweo merges with smaller nearly circular pits formed in a similar manner (see Figure 3). Southwest of the caldera there are two more of these pit craters, named Lua Hou (New Pit) and Lua Hohonu (Deep Pit). From the caldera at the summit of the mountain there extend outward two prominent zones of fracturing — rift zones. The rift zones are marked at the surface by many open fissures and cinder and spatter cones built during eruption by the accumulation of spatter and fragments of lava thrown into the air as fountains of liquid lava at the source of lava flows. Some of the gobs of liquid lava solidify in the air, and pile up into loosely cemented cinder cones upon striking the ground. Others that are still liquid when they strike the ground stick together and form spatter cones. One rift zone extends southwestward from Mokuaweoweo caldera, and the other northeastward toward the city of Hilo. A much less definite rift zone extends northward toward the Humuula Saddle, between Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea. On a clear day the profile of the northeast rift zone of Mauna Loa can be seen from the vicinity of Park Headquarters as a succession of hills (cinder cones). The most prominent of these is Puu Ulaula (Red Hill), at an altitude of 10,000 feet, which is 200 feet high on its downhill side. A rest house, located in one side of this cone, provides shelter for travelers enroute to and from the summit.

PLATE 3. A river of lava on the southwest rift of Mauna Loa,

1950 eruption. NPS photo by V. R. Bender USGS photo by G. A.

Macdonald

The fresh flows of aa lava extending downslope from the rift zones appear black. The fresh pahoehoe flows may also appear black, but when light is reflected from them they appear silvery gray from a distance. Older lavas are dark gray, and still older ones reddish-brown. Lava flows commonly divide, leaving within their boundaries small "islands" of older land not covered by the new lava. These islands are known in Hawaii as kipukas. From the vicinity of Kilauea caldera the slopes of Mauna Loa show many variations in color, depending on the age and surface characteristics of the different flows. On the upper slopes of the mountain the newer black flows surround kipukas of older gray or brown lava. On the lower slopes the kipukas show as clumps of large trees, such as Kipuka Ki on the Mauna Loa Strip Road, or Kipuka Puaulu (Bird Park).

The growth of Mauna Loa was not entirely uninterrupted. On its south eastern slope, a short distance west of Hawaii National Park, is an area that received no new lava flows for many thousands of years. There stream erosion carved big valleys into the mountainside. The remains of these big valleys and the ridges that separated them can still be clearly seen inland from Pahala and Punaluu, although the valleys have been partly filled by new lava flows.

As the great cone of Mauna Loa approached its present size it appears to have become somewhat unstable. There is a tendency for the rocks to break along certain lines and for the blocks seaward from the breaks to slide outward and downward toward the ocean. These breaks are known as faults and the cliffs formed on the land surface by the movements as fault scarps. A prominent series of fault scarps, partly buried by later lava flows, lies just northwest of the road from Park Headquarters to Pahala. The faults are still active, and are the source of many earthquakes recorded on the seismographs of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

Extending inland from South Point, the Kahuku Pali is a large fault scarp marking the edge of a downsunken area on the southwest rift zone.

PLATE 4. A typical, active aa flow, with a jumbled, clinkery

surface and dense interior. USGS photo by G. A. Macdonald

Activity of Mauna Loa. Throughout the past century Mauna Loa has been one of the most active volcanoes on earth. It has erupted on an average of once every 3.8 years, and its eruptions during that period have poured out a total of more than 3-1/2 billion cubic yards of lava. The eruptions can be classified as summit eruptions — those that occur in and near the summit caldera and flank eruptions — those that occur lower on the flanks of the mountain, generally on one of the rift zones. Probably all flank eruptions begin with brief activity at the summit, followed after a few hours of quiet by the outbreak on the flank. The present quiet period of 24 years is the longest in its history. As this goes to press, in January 1975, swelling of the volcano, with many earthquakes, indicates that it is probably preparing for another eruption.

A typical eruption of Mauna Loa begins with the opening of a fissure or series of fissures, as much as 13 miles long. From this fissure liquid lava squirts in a nearly continuous line of low fountains, from a few feet to 50 feet high. This very spectacular manifestation has been called the "curtain of fire." From the fountains pour copious fast-moving floods of lava, and along the fissure lava spatter builds up a nearly continuous wall, a few feet high, known as a spatter rampart. The "curtain of fire" is short-lived, generally lasting less than a day. The upper and lower ends of the fissure then become inactive, and eruption is restricted to a few hundred yards of the central part of the fissure. The lava fountains increase in height, reaching as high as 800 feet, and debris from the fountains accumulates around them to form a cinder cone. Pumice and Pele's hair (natural spun glass) rain down on the country to leeward of the vents. A great cloud of yellowish-brown gas rises several thousand feet above the fountains. The principal flows of lava issue during this stage, which may continue for weeks or even months. Some of these flows reach the shore, and may be destructive. Eventually the abundant gas liberation and high lava fountains come to an end, and the final phase of the eruption consists of a relatively quiet outpouring of lava. It usually lasts only a few hours, but may continue for several weeks.

FIGURE 3. Map of cross-section of Makuaweoweo caldera after the

1949 eruption. Lua Poholo, East Pit, and Lua Hohonu are pit craters

formed since 1941. (Modified after Stearns and Macdonald,

1946, click on image for an enlargement in a new window).

The 1949 and 1950 Eruptions of Mauna Loa. The 1949 eruption of Mauna Loa began late on the afternoon of January 6. Lava broke out along a series of fissures which crossed Mokuaweoweo caldera and extended 1.7 miles down the southwest rift. During the opening hours of activity a flow extended 6 miles down the western flank of the mountain. Within 48 hours, however, all activity outside the caldera was over and the western flow was dead. Within three days activity was entirely confined to the southwestern edge of the caldera. Lava fountains spurting from the fissure grew gradually higher, until on January 23 they were reaching heights as great as 800 feet. A cone of pumice 1,500 feet across and 250 feet high was built, and a mile-long blanket of pumice extended leeward of the cone. More than half the caldera floor was flooded with new lava. South Pit, a pit crater adjoining Mokuaweoweo, was filled to overflowing with lava, which spilled out to form a flow four miles long on the southern flank of the mountain. Lava fountaining came to an end on February 5, but short periods of quiet overflow of lava occurred during February and March, and during April it became almost continuous. A small lava cone was built on the caldera floor east of the earlier cone, and much of the southern part of the caldera was again flooded with lava. The eruption ended late in May.

On June 1, 1950, almost exactly one year after the end of the 1949 eruption, Mauna Loa again broke into activity. At 9:04 p.m. a fissure 1.5 miles long opened along the southwest rift zone above 11,000 feet altitude. Floods of very liquid lava poured from the fissure, and a great mushroom-shaped cloud of gas rose two miles into the air, brightly illuminated by the red glare of the lava beneath, and looking much like the great cloud made by the atomic bomb explosion at Bikini. This activity lasted only about 4 hours. At 10:15 a new series of fissures started to open lower on the rift, between 8,000 and 10,500 feet altitude, and activity at these new vents replaced that nearer the summit. Big lava flows poured both westward and southeastward from the fissures. The lava was very fluid and flowed down the steep western slopes of the mountain with great speed (Plate 2). The first western flow advanced with an average speed of nearly 6 miles an hour, and at 12:30 reached the main highway around the island, destroying part of a village. At 1:02 a.m. on June 2 it entered the ocean. Two more western flows reached the ocean on the afternoon of the same day, the first at 12:04 and the second at 3:30. Where the lava entered the sea the water boiled, many fish were killed, and great billowing clouds of steam rose 10,000 feet into the air. The eruption continued with gradually abating strength until June 23.

The 1950 eruption of Mauna Loa was the greatest since 1859. Although no lives were lost it destroyed about two dozen buildings, and buried more than a mile of highway. Its six major lava flows contain on the order of a billion tons of lava.

PLATE 5. Pahoehoe lava, showing its characteristic surface. A

pahoehoe toe is advancing in the foreground. NPS photo.