|

HAWAI'I VOLCANOES & HALEAKALA Volcanoes of the National Parks of Hawaii |

|

KILAUEA, HOME OF PELE, THE FIRE GODDESS

(continued)

Lava lake activity. The feature that made Kilauea famous among volcanoes was the presence, through the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th century, of an almost continuously active lake of liquid lava at Halemaumau (Figure 5). Other lava lakes existed for short periods elsewhere on the caldera floor, but throughout history Halemaumau has been the principal place of activity. Lakes have also existed in other craters for short periods during recent years.

Halemaumau appears to mark the point where the principal lava conduit of Kilauea reaches the surface. Near the surface the conduit is roughly cylindrical, or pipelike. During the period of lava lake activity, previous to April 1924, the upper end of the conduit contained a plug of semisolid lava, resembling aa in appearance, and known as epimagma. Fissures extending through this plug allowed liquid lava from below to rise to the surface, where it formed a shallow pool, about 50 feet deep, on the top of the epimagma. The lava of this pool was termed pyromagma. It was thinly fluid and free-flowing, and congealed to form pahoehoe. Both the pyromagma and the epimagma were free to move up or down in the conduit, either independently or together. Owing to its greater fluidity the pyromagma generally rose or sank more rapidly than the epimagma. Crags of epimagma projected through the pyromagma as islands in the lake (Plate 10), and at times the lateral shifting of these crags gave the false appearance of islands floating on the lake. The pools of liquid pyromagma continually changed in form, size, and number with changes in the depth of the pyromagma and the configuration of the top of the semisolid plug on which it rested.

PLATE 10. Close-up view of islands in the lava lake in

Halemaumau, September 20, 1921. USGS photo by T. A. Jaggar

In the Halemaumau lake pyromagma rose through source wells and left the lake again through sink-holes. A constant current flowed from source wells to sink-holes. Crusts formed continuously on the surface of the lake, owing to cooling. The fluid lava flowed beneath the crust and dragged it along, folding it into forms resembling heaps of rope or folds of cloth, or breaking it into cakes like those of ice on a river, Many of the fragments tilted on edge and sank into the fluid lava. Others were swept down into the sink-holes. Lava fountains a few inches to 30 feet high played on the surface of the lake, Some of them remained nearly stationary, marking underlying source wells or sink-holes. Others were short lived and constantly shifting, commonly occurring at spots where fragments of crust had just sunk. The temperature of the pyromagma ranged from about 860° to 1,175° C. In small cones over sink-holes, where volcanic gases mixed with air and burned, temperatures reached as high as 1,350° C. (2,460° F.).

At times the pyromagma drained away, leaving exposed the glowing epimagma that formed the bottom of the lake. At other times both pyromagma and epimagma sank, sometimes as much as several hundred feet in a single day. Such rapid sinkings were generally accompanied by avalanches of glowing material from the walls of the pit, the floor of which was commonly obscured by dense clouds of dust-laden sulfurous fume.

PLATE 11. The orchids in the foreground frame the cinder cone

and lava fountains of the Kapoho eruption, 1960. NPS photo by R.

Haugen

Explosions of 1924. During late January, 1924, the lava lake in Halemaumau was vigorously active, and its level only 105 feet below the rim of the pit. In February the lake level dropped to 370 feet below the rim, and this condition continued through March. During April a large number of earthquakes occurred on the east rift of Kilauea, the quakes progressing in general from the vicinity of the caldera toward the east end of the island. At Kapoho, near the east cape, about 200 earthquakes were felt on April 22 and 23. This suggested a cracking open of the east rift of the volcano, and tremor registered on the seismographs suggested the movement of magma out through this rift. On April 29, 1924, subsidence resumed at Halemaumau, and by May 6 the pit was more than 600 feet deep. On May 11, explosions occurred, throwing rock fragments out of the pit. On May 13, five more explosions occurred, throwing rocks as much as 2,500 feet into the air. Thereafter the explosions steadily increased in violence until they reached a maximum on May 18. Great clouds of dust rose more than 20,000 feet into the air (Plate 9). Violent lightning storms were accompanied by rains of mud. Blocks of rock weighing several tons were thrown as much as half a mile from the pit. One man who ventured too close was fatally crushed by a falling rock and hurtled by hot ash. (He is the only recent casualty of Hawaiian eruptions.) As the explosions progressed the walls of Halemaumau caved in, and its diameter increased from about 1,400 to 3,000 feet. After May 18 the explosions decreased in intensity, and the dark cloud of dust gradually was replaced by a white cloud of pure steam. The last strong explosion occurred on May 24.

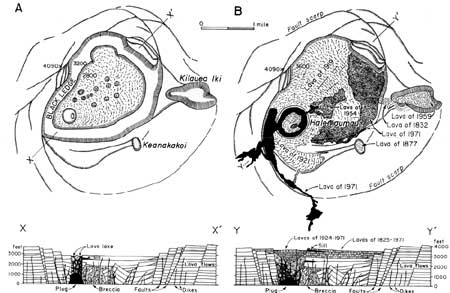

FIGURE 4. Maps and cross-section of Kilauea caldera in 1825

(after Malden) (A), and in 1972 (B). Note that the large central pit of

1825 has been entirely filled with new lava. The structure beneath the

caldera is hypothetical. (Modified after Stearns and Macdonald,

1946, click on image for an enlargement in a new window).

Many of the blocks thrown out by the explosions were red hot, but none of them were new volcanic material. All were merely fragments of the old solid walls of the pit. The gas liberated during the explosions was entirely steam. No typical magmatic gases were detected. Thus it appears that the explosions did not originate in the magma body beneath the volcano. It is believed that the great subsidence of the magma beneath Halemaumau allowed ground water from the surrounding rocks to flow into the conduit. As this water encountered the very hot walls of the conduit it was quickly changed to steam. The steam was partly confined by the mass of rock debris that avalanched in from the upper walls of the pit, and escaped violently in a series of explosions, carrying with it rock fragments and dust. Such explosions, caused by the volcanic heating of ground water, are known as phreatic explosions.

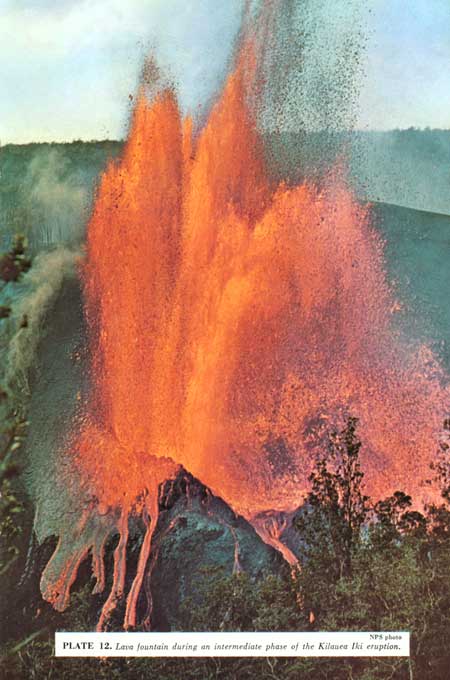

PLATE 12. Lava fountain during an intermediate phase of the

Kilauea Iki eruption. NPS photo.