|

HAWAI'I VOLCANOES & HALEAKALA Volcanoes of the National Parks of Hawaii |

|

KILAUEA, HOME OF PELE, THE FIRE GODDESS

(continued)

The eruptions of 1959 and 1960. In early October 1959, earthquakes at Kilauea caldera began to increase in number, and by early November as many as 1,500 a day were being recorded. Most of them were very small. At 8 p.m. on November 14 a crack opened on the Southwest wall of Kilauea Iki, about 300 feet above the floor. (Kilauea Iki is a pit crater immediately adjacent to the eastern edge of Kilauea caldera.) A line of lava fountains 1,200 feet long spurted up along the crack, and cascades of lava poured into the crater, burying the old floor of 1868 lava (Plate 13). By next morning, however, only two fountains remained active. One stopped that afternoon, and for two days the other was only 50 to 100 feet high, but on November 17 it began to grow in height, reaching more than 1,000 feet on November 19. By November 21 the pool of lava in the crater was 300 feet deep, and had buried the vent from which the fountain was spurting. That evening the fountain suddenly died, and for 4 days there was no activity. Then began a series of 16 brief eruptive phrases, each lasting from 2 to 32 hours (Plate 12). At the end of each, liquid lava drained from the pool back into the vent.

FIGURE 6. Diagram illustrating the probable internal structure

of Kilauea volcano. Note that although the walls of the magma reservoir

within the cone appear sharp in the diagram, they probably are actually

gradational. Fissures tapping the magma chamber lead upward to the

caldera and laterally into the rift zones. (Modified after Eaton and

Murata, 1960, and Macdonald, 1961.)

The lava fountain reached a maximum measured height of 1,900 feet, the greatest ever recorded in Hawaii. This resulted from an unusual abundance of gas in relation to the amount of liquid lava. Cinder and spatter from the fountain piled up on the crater rim, building a conical hill 150 feet high, and burying the former road. Pumice formed a blanket as much as 5 feet thick half a mile from the vent. When the eruption ended on December 21, the pool of new lava in the crater was 380 feet deep.

On January 14. 1960, eruption broke out again, this time on the east rift zone of Kilauea 28 miles east of the caldera, and only one quarter mile north of Kapoho village. For a few hours the line of small lava fountains was half a mile long, but the eruption was soon concentrated at one place, where a voluminous double fountain at times reached a height of 1,500 feet. Lava poured eastward into the ocean (Plate 15) and spread out to form a fan-shaped flow that eventually covered an area of 4 square miles. Most of Kapoho village, and much valuable agricultural land were destroyed, but extension of the island into the ocean created some 500 acres of new land. The eruption ended on February 19.

Heating of near-surface brackish ground water by the rising lava produced semi-explosive outrushes of steam, carrying with it clouds of black volcanic ash (Plate 14). Like that of 1959, the lava was unusually rich in gas, resulting in a large amount of cinder that fell over an area of several square miles and piled up round the vent to form a cone 350 feet high.

As magma fed the Kapoho eruption, the entire top of Kilauea subsided. There was actual collapse within Halemaumau crater, where lava that had remained liquid since the 1952 eruption drained away and the floor bowed downward into a basin 150 feet deep, within which localized collapse formed three circular pits (Figure 7). Two of the pits lay on the line of the eruptive fissure active in 1952 and 1954. The central pit was at first about 150 feet deep, but was partly refilled by lava squeezed from beneath the collapsing crust.

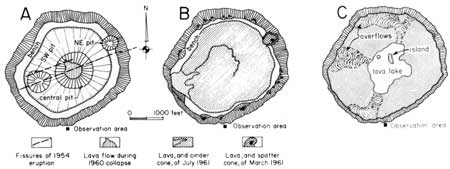

FIGURE 7. Maps of Halemaumau Crater showing the row of pits

formed across its floor by collapse during the 1960 flank eruption (A),

the pools of lava formed in it by the eruptions of 1961 (B), and the

lake on the crater floor in January 1968 (C). (click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

Internal structure of Kilauea. The sinking of the top of Kilauea volcano during the flank eruption at Kapoho was part of a general pattern of behavior of the volcano. Very early in the history of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (see page 56) it was found that the ground surface on the slopes of the volcano was constantly tilting in one direction or another, and it was soon shown that this tilting correlated with activity of the volcanoes. Preceding eruption the whole volcano swells up, as though it were being inflated like a big balloon. This produces an outward tilting on its sides. Following the eruption the volcano contracts and the slopes tilt inward. This swelling and tilting can be measured by leveling, of the sort done in ordinary surveying. By leveling from sea-level at Hilo, it was found that during the interval from 1912 to 1921 a bench mark near the observatory apparently rose about 3 feet. Releveling in 1927, after the great collapse and steam explosions of 1924, showed that the same bench mark had lowered 3.5 feet, while a bench mark near the rim of Halemaumau had gone down about 13 feet. Ordinarily, however, the tilting of the ground surface is measured not by leveling, but by instruments known as tilt-meters. Such tilt-meters in operation by the observatory are capable of indicating an angle of tilt of less than one-tenth of a second. (A tilt of one-tenth of a second would raise the end of a board ten miles long a quarter of an inch.) Volcanic tilt of many seconds of arc has been measured on the tilt-meters. Strong outward tilting of the ground surface, especially when combined with numerous earthquakes, is a good indication of magma rising in the volcano and the possibility of impending eruption.

Study of the patterns of swelling and shrinking of Kilauea, combined with earthquake patterns, has led to the conclusion that the volcano contains a reservoir in which magma gradually accumulates preceding an eruption (Eaton and Murata, 1960; Macdonald, 1961). This storage reservoir appears to be at a depth of only about 2 to 2-1/2 miles below the summit of the volcano — that is, actually within the volcanic cone at a level above the surrounding ocean floor (Figure 6). Other evidence indicates that the magma is formed at a depth of 30 to 40 miles within the earth. From this relatively deep source it rises into the shallow reservoir, causing inflation of the volcano. Eventually, rupturing of the roof of the reservoir releases magma to the surface, bringing about an eruption. The amounts of lava poured out during summit eruptions commonly are too small to cause much contraction of the volcano, but the relatively much larger amounts of magma that are injected into the rift zones and poured out as lava flows during flank eruptions cause a contraction of the cone with sinking of the summit, like that during the 1960 eruption.

Typically, the eruptive pattern of Kilauea consists of a swelling of the volcano, followed by one or more summit eruptions, and this in turn by a flank eruption accompanied by shrinking of the volcano. The 1952-55 and 1959-60 eruptions, with the swelling and shrinking that preceded and accompanied them, were good examples of this pattern, as also were the eruptions of 1961, described in the next paragraph.

PLATE 14. Steam roars from vents at Kapoho, January 1960,

while nearby fountains throw lava. The gray color of the steam cloud is

caused by fine volcanic ash. NPS photo by W. W. Dunmire

Eruptions of 1961. Only 4 months after the end of the 1960 eruption and the shrinking of the volcano that accompanied it the volcano began to swell again, and by February 1961 an estimated 70,000,000 cubic yards of new magma had been pumped into the shallow magma reservoir (Richter and others, 1964). At 7:20 a.m. on February 24 eruption broke out in the northeasternmost of the three pits formed by collapse in Halemaumau a year earlier, and lava poured rapidly into the pit. The eruption stopped in mid-afternoon, and by the next morning all but about 30,000 of the 300,000 cubic yards of new lava had drained back into the vents.

Two other short eruptions took place in March and July, and by the time the latter eruption ended, on July 17, the new lava bad filled the central basin in Halemaumau to a depth of 210 feet (Figure 7B).

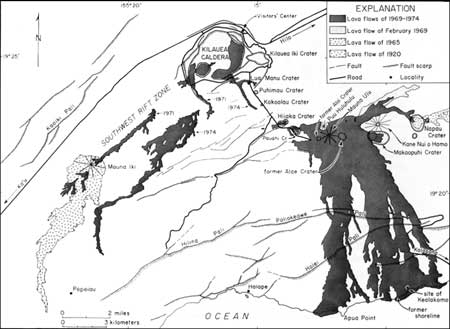

None of these three brief summit eruptions brought about any appreciable interruption of the swelling of the volcano, and by September the degree of swelling was nearly as great as it had been before the eruption of 1960. On September 21, 1961, very numerous earthquakes commenced on the rift zone of the volcano near Napau Crater, 5 miles east of the summit. These continued through September 22, and at the same time the summit of the volcano began to sink rapidly as magma moved out from beneath it into the fissures of the rift zone. On September 22 small lava flows were erupted just east of Napau Crater (Figure 8), and on the 23rd two more outbreaks occurred 5 and 8 miles east of Napau. Activity ceased on September 24. Sinking of the summit of the volcano stopped with the end of the flank eruption. Although 13 small lava flows were formed along a 12-mile stretch of the rift zone (Figure 2), the total volume of lava extruded was only about 3 million cubic yards. In contrast, the sinking of the mountaintop indicated a drainage of about 70,000,000 cubic yards of magma from beneath it. Most of the magma must have remained to form dikes in the fissures of the rift zone.

FIGURE 8. Map of part of Kilauea Volcano, showing the Chain of

Craters and recent lava flows. (click on image for an enlargement in a

new window)

Eruptions of 1962-65. Swelling of Kilauea volcano commenced again almost immediately, and by December 1962 had reached nearly the degree it had before the 1961 eruption. On December 6 many small earthquakes were recorded from the east rift zone about 0.6 miles south of Aloi Crater (Figure 8), the summit of the volcano started to sink, and continuous trembling of the ground ("volcanic tremor") indicated the movement of magma beneath the surface from beneath the caldera out into the east rift zone. On December 7 eruption broke out in Aloi Crater (Figure 8), and during the next 36 hours 5 more outbreaks occurred along a line between Aloi Crater and Kane Nui o Hamo. At each the activity lasted only a few hours, and the eruption was essentially over by the evening of December 9. The total amount of lava extruded during the eruption was about 425,000 cubic yards, but of this only about 155,000 cubic yards remained on the surface. Sinking of the mountaintop indicated a drainage of about 10,000,000 cubic yards of magma from beneath the summit region, but more than 98 percent of it remained beneath the surface in the rift zone. This transfer of magma into the rift zone resulted in swelling of the rift zone, with a rise of the ground surface near Alae Crater of about 2.5 feet (Moore and Krivoi, 1964).

Three more episodes of magma migration from beneath the summit of Kilauea into the east rift zone occurred on May 9, July 1, and August 3, 1963. Each was accompanied by numerous earthquakes, slight sinking of the summit region, and swelling of the rift zone, but without actual eruption. On the afternoon of August 21 the same phenomena indicated still another movement of magma (Peck, Moore, and Kojima, 1965), and about 6:20 p.m. molten lava broke out along a series of fissures that extended across the floor of Alae Crater (Figure 8), up its north wall, and into the forest just north east of the crater. By the end of the eruption, on August 22, the lake of lava in the crater was 62 feet deep, but the surface of the lake gradually sank about 12 feet, leaving a pool 1,000 feet across and 50 feet deep.

Kilauea quickly recovered the small amount of shrinking that resulted from the 1963 eruption. Volcanic tremor commenced at 8:01 a.m. on March 5, 1965, and at 9:43 eruption broke out along a series of fissures that extended from the western edge of Makaopuhi Crater (Figure 8) eastward through Napau Crater for a distance of about 8 miles. Simultaneously, the summit of the volcano began to sink. During the first 8-1/2 hours more than 20,000,000 cubic yards of lava was extruded. Lava streamed into the deep pit at the western end of the double pit crater of Makaopuhi from fissures in its wall, and formed a pool nearly 200 feet deep. Another pool in Napau Crater reached a maximum depth of 40 feet, but about half of the lava drained back into the underlying vent fissures, leaving a permanent fill only 20 feet deep. Near Napau a forest of tree molds was formed (Plate 16).

Activity ceased at about 4:30 p.m., but resumed on March 6, and for 4 days weak intermittent fountaining continued at several vents along the rift zone east of Makaopuhi Crater, liberating 2 or 3 million cubic yards of lava.

About 1:30 a.m. on March 10 the weak activity along the rift zone stopped. Simultaneously the volume of lava output and intensity of fountaining in Makaopuhi Crater began to increase, and the temperature and fluidity of the erupting lava also increased, suggesting the arrival of new magma from greater depth. At the end of the eruption, on March 15, the lake of new lava in the western pit of Makaopuhi Crater was 340 feet deep, with a volume of about 9,000,000 cubic yards; but during the next 4 days about 2,500,000 cubic yards of lava drained back into the vents, lowering the lake surface about 50 feet.

Still another small eruption took place on the east rift zone of Kilauea on Christmas eve, 1965. For about 6 hours lava fountains played along fissures extending about 2 miles eastward from Aloi Crater, and a cascade of lava poured down the crater wall onto the floor. The year 1965 ended with sinking of the summit region of Kilauea and inflation of the adjacent east rift zone.

PLATE 17. Halemaumau Crater and fume cloud illuminated by the

glowing lava beneath; seen from the Volcano House, November 27,

1967. NPS photo by Cecil W. Stoughton