|

Mesa Verde National Park has, from its very beginning, made use of Navaho Labor on such jobs as road and trail work, building maintenance and ruins repair. At times as many as fifty Navaho men have been employed during the summer months, but in recent years this work has been done largely with CCC labor. At present there are only a few Navahos working on the mesa. They have been employed by the government because they are good workers, and because, having always been self supporting, they are so eager to work. The Navahos, as a tribe, are a proud, independent people and are willing to do any kind of work in order to maintain this independence. It is probably this tribal feeling that has enabled them to increase even under adverse conditions. They live in the park much as they do on the reservation. The little group of hogans is over on the rim of Spruce Tree Canyon, only a quarter of a mile from our own residential area. In the summer outdoor cooking fires are used and the women set their looms up under the trees. At night the men sing and dance, practicing for the Yeibichais and Squaw Dances that they will attend on the reservation. We have grown to love the sound of the clear, high calls in their songs, and the thump of moccasined feet on the resonant earth. We listen for it and it is as natural as the voices of the coyotes and owls; it is a part of the life of the Mesa Verde. Naturally, through years of living together, as in a small village, we have come to know our neighbors rather well. Unusual individuals stand out among them and intimate happenings endear them to us.

Sandoval Begay, son of the famous old medicine man. Sandoval, works for us during the summer but returns to the reservation in the winter. Always at Christmas time, though, he comes back. He comes to wish us a "Mehwi Kismus" and to bring us news from the reservation. And, of course, to accept the turkey and trimmings that we save for him from the Christmas table. This last Christmas we asked all of the Navahos to come to the house when Sandoval came. Some went to church at Shiprock in the morning but all were gathered at the house by dusk. Twenty five were in the room, sitting on the floor and on couches; dressed in their very best. It was a beautiful sight in the light of the open fireplace and the bright-colored Christmas tree globes, happy faces, shining teeth and glossy hair; velvet blouses setting off the silver necklaces and bracelets and always the snap-snap of chewing gum. Small, dark children, scrubbed clean, played with our own around the Christmas tree. It was a happy time for all. They embrace our Christmas customs quite completely, influenced somewhat by their contact with the missions on the reservation. Many say it is because they get a free treat and gifts from the church at Christmas time. That may be true to some extent, but the Navajo has a sense of giving that is all his own. It is a feeling he has throughout the year and enmeshes nicely with our custom of giving at Christmas. When a Navaho goes to visit a friend whom he has not seen for some time he takes him a present. When that Navaho returns the visit he also brings a present, usually a little better than the one he received. Once old Navaho Jim, who was long one of our favorites, was visited by a friend from over the Lukachukai Mountains. This friend brought Jim a fine sheep pelt. The next summer when Jim returned his visit he gave his friend a small saddle blanket his wife had woven. After a time the friend came to see Jim again, and this time he presented him with a sheep. Old Jim, in return, on his next journey across the mountains, gave his friend a fine piece of buckskin. A year or two passed before the friend came back, but when he at last appeared he brought Jim a fat, young cow. Navaho Jim was never able to repay this last visit. He was an old man, with very little property, and he had nothing better than the cow that he could take to his friend.

One Christmas we received a package that Nakaidenez Begay had sent up from the reservation. The accompanying letter said, "I am senting you two goat skins the big one has lice they are a gif to you." This Navaho's letters are always interesting. He went to a mission school four years but that was twenty five years ago. His use of words and his punctuations and capitalizations are unique. Always his letters close with, "Many good lucks to you." Last spring one of the Navaho men came up from the reservation with the best case of nerves that could possibly be imagined. He had been at the Day School the day before, waiting for a ride, when one of the teachers collapsed at his side and died in a short time. Being the only man present he had been forced to help carry her into the house. Now he felt that he was a marked man. He had been in the presence of death; had actually touched it, so there was nothing that could save him. The terrible fear that Navahos have of death made him feel that his actual contact with it could mean only one thing; his own death. He felt that the Chindes (evil spirits) were on his trail and that there was no escape. To all appearances he was a very sick man: he couldn't eat, he couldn't sleep, he was so weak that he could hardly do his work. A long-healed-over ax cut on one foot began to pain him so that he could hardly walk. He lost weight; worst of all, his spirit was completely broken. He had been too well schooled in the white man's ways to run away when death had come; he had stayed to help with the woman as best he could, but no amount of the white man's training could give him enough strength of mind to put aside the curse of the Chindes. We tried to laugh him out of it; gave him medicine for all of the things he thought he had, and tried to keep the incident out of his mind. Only time effected a cure. Weeks passed and to his surprise he was still alive. Slowly he began to improve but it was months before he was completely well again. Today he is apparently in good health but if an accident or some sickness should come he would immediately ascribe it to that unfortunate incident. This curious mental trait of the Navahos may explain some of the seemingly miraculous cures effected by the medicine men in their ceremonies. If the patient is suffering from anything that is in any way caused by a mental attitude, the ceremony has a good chance to succeed. Lasting for many days and bearing the constant implication that a cure is coming, it probably enables the patient to put the trouble aside.

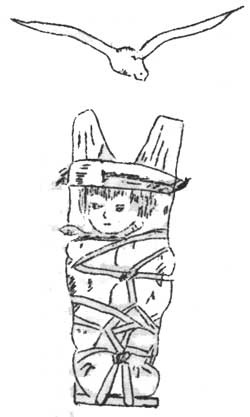

When our baby was born one of the first callers at the park hospital was Paul Lee, a Navaho. After admiring the baby for a time he told me of an incident that had happened that same afternoon. As four of the Navahos were working on a trail they discovered a nighthawk on its nest. Nighthawks will stay on their nests in the face of almost any danger, so by creeping up very slowly Sam Yellowhorse was able to capture the bird under his hat. Johnny Hay opened up his little buckskin pouch of corn pollen and sprinkled the pollen into the feathers of the bird. Then, very carefully, they shook the pollen out of the feathers onto a handkerchief that one of the men had spread on the ground. After this the bird was released and each man tied a little of the corn pollen up in a rag and carried it home. There it was transferred to a tiny buckskin bag. Each man would keep this bag of pollen until his next child was born, then he would tie it to the cradle board. To the Navahos the nighthawk is a symbol. It sits quietly on its nest all day long and is not easily alarmed by noises or movements. Its feathers are soft and make no sound in flight. To the Navahos this bird is a symbol of quietness and rest, and the corn pollen that has touched it, when tied to the cradle board, will cause the baby to be quiet and restful in the daytime, and to sleep soundly at night. Very often odd little trinkets may be observed tied to Navaho or Ute cradle boards: always they have some significance according to the beliefs of the Indians. During the last two years the Navahos have been aroused by the request of the Indian Service to cut their flocks of sheep and goats down to very small numbers. They were afraid that there was some ulterior motive back of this because the sheep and goats were their most prized possessions. Our Navaho foreman, Sam Akeah, of whom Deric Nusbaum wrote so much in his book, "Deric in the Mesa Verde," had his own slant on the matter. "The Government wants us to sell our sheep and goats because they eat all of the grass off the land and the dirt washes away, and it's going to fill up the Boulder Dam." That Sam may have been partly right is shown by the recent efforts of the Government to perfect a method by which they can get rid of the silt in the Little Colorado River, which is on the Navaho reservation, before it washed down to settle behind the Boulder Dam. Most of the Navahos are shrewd business men and can usually drive a good bargain. Perhaps we should except automobile buying, for they all covet an automobile and the places it will take them. Hosteen Nez (Tall Man) came up early one spring, looking for work. The Superintendent explained that it was too early. The next day Hosteen asked again: still there was no work. It was a long way back to the reservation so Hosteen decided to wait until there would be a job for him. All of the people in the park liked Hosteen. He was a handsome old man, a "long-hair," meaning that he was an old timer who had never been to school. He had no food and his clothing seemed thin for the cold nights, so they supplied him with all of the things he needed. Each day he would go from door to door, for hand outs, paying for them with great quantities of conversation—in Navaho. He could eat half a dozen meals in a row without the slightest trouble. At last a job was ready for Hosteen and everybody was very glad for now he would be able to earn the money that he seemed to need so badly. Before starting to work he went to the clerk in the office and handed him fifty dollars. Calling in an interpreter he explained that he wanted the clerk to keep it so he would not lose it while he worked. And to me he brought a beautiful necklace of turquoise, shell and coral, and asked me to keep it while he worked. He could have pawned it for eighty dollars at any trading post.

We find the old men especially enjoyable. At one time we had three of them: Navaho Jim, whom I have mentioned, Saltwater, the practical joker, and Joe Holly and his burro. Joe Holly was a great story teller for he had travelled far beyond the reservation. He had worked along the Snake River, in Idaho, and had herded sheep on an island near San Francisco. When the man for whom he worked shipped the sheep to Australia, Joe went along. He visited the Hawaiian Islands and saw the dancing girls. When he got back to San Francisco he was paid off with gold dust. As a result of these travels Joe's stories were endless, and he told them well. Being an old man he was listened to with much respect by the younger men. The last year Joe Holly was in the park he was too weak to work and spent most of his time under his little lean-to. People often took food to him but he would accept it only when they assured him that, "we give you this because we like you, not because we are sorry for you." The Navahos say all of that in one word. Late at night when all was quiet Joe would go on telling his interesting tales, with only his burro as a listener. Perhaps Joe did not know he was thinking out loud—he was deaf. As a rule the old men are quiet and reserved, but the younger ones, especially those with a keen sense of humor, are often gay and flippant. One day one of the young men, whom we call the "Chimney Sweep," because he dislikes that task especially, had been called to one of the houses to clean out a stove that refused to drew. "Did you get it cleaned out?" I asked him later. "Oh yes, I got it alright," he answered. "How did you do it?" "Oh, I just sprinkled a little corn pollen on it and said a prayer." | ||||||

| <<< Previous | > Cover < | Next >>> |

vol7-1c.htm

14-Oct-2011