|

Very often, in excavating and examining the ruins on the mesas and in the caves, people have picked up prehistoric stone implements and wondered about their origin. Even today, visitors find tools that were fashioned by the early stone workers. A brief study of these tools reveals that they are not all made of the same material and the question of the source of each type of rock immediately arises. The rocks occurred naturally as constituents of the earth's crust and they must have outcropped in the nearby regions where they were readily available to the Indians. Because the ancient stone workers are not living today we cannot ask them where they obtained the various rocks. Sources can be learned only by comparing the materials used by the ancients with the existing formations. Several problems are to be considered. First we must learn the composition of the rocks used for the various tools. A study of all of the rocks of the region can then be made in an effort to determine the source of each variety. In addition, a careful check of the material used in each type of tool may reveal whether the Indians selected certain rocks for each purpose or whether they used them at random. Because of the lack of a laboratory with suitable equipment, only field nomenclature was used in identifying the materials from which the stone implements were made. The rocks were named according to the United States Geological Survey standards which are very similar to the classifications in "Field Geology," by F.H. Lahee, 1931, and "Handbook for Field Geologists" by C.W. Hayes 1909. The only variation was in the use of the term siltstone, which was used to represent a very fine-grained sandstone or arenaceous shale. Technically speaking, it is a rock consisting of quartz grains from .05 millimeters to 0.1 millimeters in diameter, generally too small to be seen by a ten-power lens. In some cases, especially when the tool was polished, it was very difficult to identify the material without chipping the worked tool, so in order to keep from defacing the specimens the closest approximate name was attached.

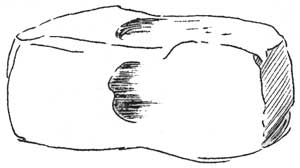

For convenience and simplicity the rocks were divided into two groups, igneous and sedimentary. Although quartzite and slate may be classified as metamorphic rocks, they were grouped under the sedimentary rocks because of their primary origin. Basalt schist and diorite gneiss were grouped with igneous rocks for the same reason. Six types of tools were considered: axes, stone hammers, hammerstones, manos, metates and abraiding stones. The last type included polishing and rubbing stones in general. A total of 381 tools was identified and the following table indicates the frequency with which each variety of stone was used in each of the six types of tools. Relation of stone type to tool type

As shown by the table nineteen different kinds of stone were used, twelve being of igneous and seven of sedimentary origin. Mesa Verde is made up of sedimentary rocks so the igneous materials presented the greatest problem. The main source of these igneous rocks proved to be conglomerate deposits of Tertiary Age, which occur on the mesa tops along the north side of the Mancos Canyon. These deposits of igneous rocks, which vary in size from gravel to boulders three feet in diameter, are not persistent, but at the southern end of Chapin Mesa one is about twenty feet thick. The deposits were left by the Mancos River when it flowed on top of the mesa. At the present time the river is a thousand feet below the mesa top. The only other possible source of igneous rocks is from the dikes which were intruded into and through the Mesa Verde formation at the close of Cretaceous time. Four of these dikes cut through the mesa and another is located just to the north.

All of the igneous rocks mentioned in the table above were found in the mesa top conglomerates but two, diorite gneiss and basalt schist. It is extremely probable, however, that these also occur. Andesite was found in the conglomerate beds but it is probable that the main source of the andesite, especially the biotite variety, was the igneous dikes, which are composed, for the most part, of this type of rock. There are some basalt dikes associated with the andesite dikes, which may have been the source of some of the basaltic rocks. Of the sedimentary rocks, sandstone, siltstone and hematite occur abundantly in the Mesa Verde formation. The sandstone is the common cliff-making rock. The hematite, which is usually very limonitic, and siltstone, occur as thin lenses of rock associated with the carbonaceous shales of the Menefee Shale, the middle member of the Mancos formation. The black, highly carbonaceous limestone and slate occur as thin lenses in the Mancos shales, which underlie the Mesa Verde formation and outcrop all along the northern escarpment of the Mesa. A hard variety of red limestone similar to that from which some of the axes were made, was found in the Tertiary conglomerates, but the gray varieties and some slates were found adjacent to the igneous dikes where they have resulted from the slight metamorphism of the sandstone and shales. The gray and green cherts are found in the conglomerate beds. From all this it can readily be seen that the Cliff Dwellers had little trouble in getting material for the tools listed in the table above. These were the tools that required large stones, but the problem of transporting the raw material was comparatively simple. None of the cliff dwellings were more than a few hours walk from the source of all of the stones used in making the above listed tools. A glance at the above chart shows that there were certain preferences as to the type of stone chosen for tools. The outstanding example was in the use of sandstone for metates. Only two out of forty metates were made of rocks other than sandstone. This choice is easy to understand. Metates were large and heavy and transporting them from a distance would have presented quite a problem to the Cliff Dwellers. A large, flat surface was needed. Such a surface is seldom found on river worn stones and the cutting of a flat surface on an igneous river boulder would have been a slow and laborious task. The utilization of sandstone for metates presented none of these difficulties. It was immediately available in the vicinity of every pueblo. It naturally breaks up into flat, thin pieces and a short search along any sandstone ledge would reveal many pieces that could be used for metates with almost no shaping. Sandstone also presented a good grinding surface, the only disadvantage being that the fine quartz grains ground off in the meal and played havoc with the teeth. Sandstone was also the predominant stone used in making manos, being used in 76 percent of the cases. Eight other varieties of stones were used occasionally for manos, but the reason was probably that small stones of the desired shape were available rather than that the Indians deliberately searched for the particular stones.

The materials from which stone axes were made show a remarkable diversity, only three kinds of the identified stones: slate, chert and siltstone being neglected. Three materials, however, seem to have been the favorites. Felsite and basalt were the most commonly used igneous rocks, having been used in 21 and 15 percent of the axes respectively, while limestone, the most commonly used sedimentary rock was used in 15 percent of the axes. All of those stones were tough, dense and homogeneous and were softer than the quartz grains in the sandstone on which they were ground. The limestone used was of a dense variety that was easily ground down, but it did not make a very serviceable axe. The five axes made of sandstone are hard to explain; certainly they could not have been very serviceable.

For hammerstones (without handles) quartzite was the favorite stone, having been used in 43 percent of the cases. Ten other types of stone however, were also used. Of the stone hammers (with handles) 29 percent were made of sandstone and 23 percent of quartzite. The series, however, is too small for any definite conclusions. Twelve different materials were used for abraiding stones, but sandstone and quartzite were the favorites, having been used in 28 and 31 percent respectively. Both of these were common and they served very well for the general purpose of pounding, rubbing and grinding.

In summing up the results of this study of 381 stone tools, one point is very evident. The Cliff Dwellers had relatively little difficulty in obtaining the stones used in the six types of tools that were studied. All were close at hand and no greater problem was involved than that of carrying them a short distance, seldom in excess of a half a dozen miles. As to whether the Cliff Dwellers chose certain varieties of stone for each type of tool we cannot be so definite. In some cases it seems that they recognized that certain stones would be more serviceable than others. In other oases a wide variety of stones was used, some of them being rather poorly suited to the purpose. It is possible that even though they did recognize the superior qualities of certain stones they did not bother to obtain them and often used whatever stones were at hand. As a result the stone was sometimes not at all serviceable for the use that was made of it. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <<< Previous | > Cover < | Next >>> |

vol8-1d.htm

14-Oct-2011