Perhaps you have wondered, whenever you have visited Mount Rainier

National Park, why you habitually find certain animals or plants at

fixed localities upon "The Mountain's" broad flanks while at other

places an entirely different assortment of flora and fauna is present.

This distribution of plant and animal life offers an interesting subject

for study or speculation. On Mount Rainier it is greatly varied and

complicated by a number of factors - chief of which is change in

altitude.

Generally speaking a change in latitude of 800 miles poleward is

equal to an ascent of one mile in altitude. Also the average change in

temperature due to change in altitude is about 1 degree for every 300

feet but on Mount Rainier these differences are more pronounced. This is

because "The Mountain" is an isolated peak and, as such, is much exposed

to radiation. An elevation equivalent to Mt. Rainier on a plateau is

greatly influenced by the great bulk of the plateau which absorbs more

heat and radiates it slower than a single exposed mountain such as this

which stands alone and overtops, by 8000 ft., its closest competitors in

height. In addition Mt. Rainier is still in the "glacial age"

(approximately 50 square miles of surface area are covered with

perpetual ice) and thus absorbs little heat even on a hot day and being

entirely surrounded by moving air currents radiates its heat with great

rapidity. The air is thinner upon the upper slopes of Rainier (an

average barometric pressure of 30 inches at sea level means that a

pressure of about 17 inches will be found on the summit of this

mountain) and this allows the actinic rays of the sun to pass through

more readily causing severe sunburn. Many a mountain climber has found

this out to his sorrow but it is also interesting to note that although

the sun's rays pass through this thin air with much more heat they cause

little change in air temperature. Instead it is used up in melting the

snow. Why then do we not find considerable running water upon the snow

surfaces of the upper elevations? This is explained by the dry air at

that altitude. The snow surface disappears without visible water, its

melting being irregular which brings about the honey-comb structure

found on the upper snow surfaces. While the air is somewhat modified by

the heat of the sun's rays, direct or indirect, a noticeable change in

temperature is characteristic here as soon as the sun sets for then the

source of the heat is shut off, radiation into the thin air is very

rapid and the air is soon very chilly. Being heavier than the warmer air

it slides down the slopes of "The Mountain" into the lower valleys and

helps to bring the colder upper temperatures into the lower valleys.

This is particularly noticeable if one stands in one of the numerous

valleys or glacial troughs in this park. After sundown a cold draught

will be experienced while the slopes immediately above it will often be

much warmer.

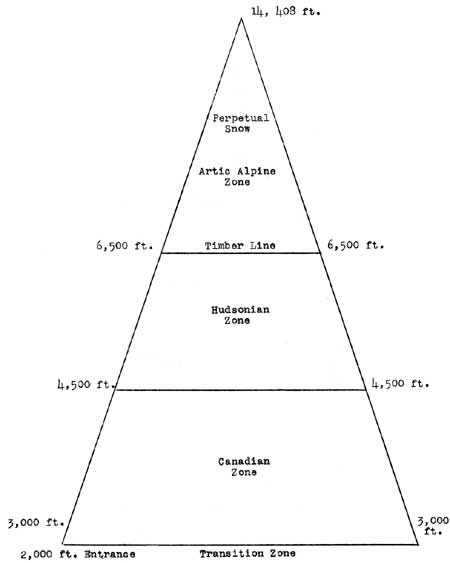

Life Zones in Mount Rainier National Park

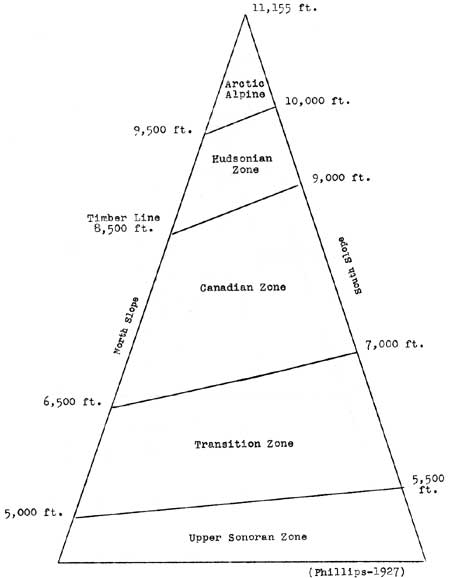

Life Zones in Yellowstone National Park

Life zones on Mt. Rainier show corresponding changes. Tree line on

the Rocky Mountains is from 9000 to 10000 feet in the same latitude and

Arctic Alpine, Hudsonian and other zones are correspondingly higher than

upon Mt. Rainier. Tree line on Mt. Rainier is from 6500 to 7500 feet and

the Hudsonian zone, corresponding in plant and animal life to the

latitude of Hudson Bay and here, the zone of greatest flower development

is between 4500 and 6500 feet while the Hudsonian zone in Yellowstone

National Park is 9000 to 10000 feet on south slopes.

Tree line as well as distribution into plant zones is along irregular

lines due to factors other than altitude alone. There are a number of

these factors to only a few of which we can call attention in this

article. Tree line and plant distribution differs on the North and South

slopes of Mt. Rainier. Snow fall is much heavier on the south and west

slopes but on the other hand south and west slopes are inclined to the

sun and receive the more direct rays and are warmer. Contrary to common

belief park lands on the north side of mountain are free from snow

earlier in the season than parks at the same altitude on the south side

and on an average have a more dry climate. As an example of this factor

in plant distribution Spruce and Ceanothus are quite common on the North

side of the mountain and not found on the South side.

Glacier tongues also extend far down toward the base of the mountain

and glacial streams extend below these. Both of these carry the colder

temperatures from above down into the lower altitudes and arctic alpine

flowers are found not only along the edge and at the ends of the

glaciers but for several miles below along the edge of the glacial

streams. At Longmire five miles below the end of Nisqually glacier one

can find along the bowlder strewn stream course several plants that

normally live at much higher altitudes.

Local disturbances of zonal distribution such as slope, streams,

winds and snowfall are much more noticeable on Mt. Rainier than in

latitude affects because of the compressed character of the zones on Mt.

Rainier. Fifty or one hundred miles of latitude will now show many times

as great a change in plants as the same number of feet will show on the

mountain. This is well shown at the end of Nisqually glacier where large

trees are growing at the same altitude as the arctic alpine plants near

the glacier's edge.

Soil and moisture are both important factors in plant distribution.

Both of these factors along with exposure to winds greatly effect tree

line. Many ridges are devoid of soil especially at high elevation and

most of the soil found at high elevation is pumice. Both rock ridge and

pumice are xerophytic or dry habitats and unfavorable to tree growth but

quite favorable to other plants of more hardy character.

The region above the tree line, the arctic-alpine, is a region of

rock ridge, pumice slope and snow and ice. The plants of this region are

all stunted because of adverse conditions of growth. These adverse

conditions however make this region the most definite of all the plant

zones on the mountain. Only a few plants are able to adapt themselves to

this harsh habitat. The arctic-alpine plants differ little throughout

the whole Cascade Sierra Nevada range and are partly remnants of the

arctic plants driven southward by the ice advance of the glacial period.

At the close of the glacial period many of these plants followed up the

retreat of the glaciers northward. But a great many finding the same

arctic conditions of environment upon our high mountains have remained

and are now marooned on our barren mountain tops surrounded by much more

favorable conditions. The Ptarmigan, an arctic bird, is the only animal

of this region having the same relationship to the glacial age as the

arctic plants. This bleak habitat seems to be preferred by this bird and

these plants.

"There is no Northern shore so bleak

No mountain top so bare

There is no desert so accursed

But God's gems blossom there."

Charles Landes,

Ranger-Naturalist.