TREES OF MT. RAINIER NAT'L PARK

Probably the first feature of interest which catches the eye of the

visitor is the magnificent stand of timber that clothes the lower slopes

of "The Mountain". And no wonder! It is representative of the timber

of the Pacific Northwest, a region famed far and wide as the greatest

timber region in the world. Our trees are not of the greatest diameter,

nor do they claim the record in height but they strike a happy medium in

these two factors which is enhanced by a density of stand that is

probably unrivaled by any similar sized trees anywhere in the world.

Here we find great Douglas Firs, Hemlocks and Western Red Cedars up to

ten feet in diameter and in some cases over 250 feet tall, growing so

close together that their branches interlace far overhead to form an

evergreen canopy that serves as an almost impregnable barrier to even

the brightest sun's rays. For approximately two thirds of their height

these trees are clean and barren of limbs and in their symetrical form

one can easily visualize the stately pillars of some ancient temple.

Probably the first feature of interest which catches the eye of the

visitor is the magnificent stand of timber that clothes the lower slopes

of "The Mountain". And no wonder! It is representative of the timber

of the Pacific Northwest, a region famed far and wide as the greatest

timber region in the world. Our trees are not of the greatest diameter,

nor do they claim the record in height but they strike a happy medium in

these two factors which is enhanced by a density of stand that is

probably unrivaled by any similar sized trees anywhere in the world.

Here we find great Douglas Firs, Hemlocks and Western Red Cedars up to

ten feet in diameter and in some cases over 250 feet tall, growing so

close together that their branches interlace far overhead to form an

evergreen canopy that serves as an almost impregnable barrier to even

the brightest sun's rays. For approximately two thirds of their height

these trees are clean and barren of limbs and in their symetrical form

one can easily visualize the stately pillars of some ancient temple.

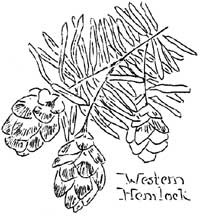

The accompanying sketches illustrate the character of the cones which

serve as the principle means of identification. That of the Douglas

Fir, our best known species, is distinctive in that it has three

cornered bracts protruding from between the cone scales while the

Western Hemlock produces numerous, tiny cones about three quarters of an

inch long. The Western Red Cedar has a historic background. Its lumber

is straight grained and easily split so that the early settlers in this

region found it adapted to a variety of uses. The walls of their cabins

were of the logs of the cedar while shingles for their roof and puncheon

for their floors were split from this lumber. They were thus spared the

labor of hewing such material as the settlers in the eastern states were

forced to do during an earlier period in the history of our country.

However neither this tree nor the Alaska Cedar are true cedars. They

are known in botanical circles as Thuya plicata and Chamoecyparis

nootkatensis respectively. Here they answer to either their common or

scientific name and so you may take your choice.

The accompanying sketches illustrate the character of the cones which

serve as the principle means of identification. That of the Douglas

Fir, our best known species, is distinctive in that it has three

cornered bracts protruding from between the cone scales while the

Western Hemlock produces numerous, tiny cones about three quarters of an

inch long. The Western Red Cedar has a historic background. Its lumber

is straight grained and easily split so that the early settlers in this

region found it adapted to a variety of uses. The walls of their cabins

were of the logs of the cedar while shingles for their roof and puncheon

for their floors were split from this lumber. They were thus spared the

labor of hewing such material as the settlers in the eastern states were

forced to do during an earlier period in the history of our country.

However neither this tree nor the Alaska Cedar are true cedars. They

are known in botanical circles as Thuya plicata and Chamoecyparis

nootkatensis respectively. Here they answer to either their common or

scientific name and so you may take your choice.

Among the pines we have the Western White Pine, the Lodgepole Pine and

the White Barked Pine -- the latter being a very picturesque tree of the

rugged timberline regions. Here were often find it gnarled and twisted

by the unfavorable elements with which it wages a constant battle. Its

allies in this struggle are the Alpine Fir and the Mountain or Black

Hemlock -- which lend a picturesque touch to the high, sub-alpine parks,

including the justly famous Paradise Valley.

These are all cone bearing trees -- our forests here may be

considered as being almost wholly of that type. The "hardwoods" or

"broad leaved" trees -- that is those which lose their leaves in the

fall -- are of minor importance. There are only a few species of this

latter type here. Most important are the alder, cottonwood and maple

which lend a touch of bright green in the spring and a dash of autumnal

brilliance in the fall. As a matter of fact there are but twenty

species of trees in the Park -- and yet it is regarded as being

representative of the finest stands of timber on earth. To see it is

convincing proof of this fact.

THE WATER STRIDER

Everyone knows the Water Striders -- those bugs with the long legs

that dart here and there about the surface of pools and on the streams

wherever the waters are not to boisterous. A small, land locked pool on

the Nisqually River Bar contained several of these well known bugs -- to

call them bugs instead of insects is not incorrect for they belong to

the insect order that may be correctly known as such. A sudden shove of

their long legs would send them gliding over the surface for a few

inches, probably seeking some unwary midge or small aquatic insect. No

doubt you have seen them in the streams near your home. Look for them

and if you find them call them by their pet name -- Hygrotrochus remigus

-- if you can pronounce it.

Click to see a copy of the original pages of these

articles (~225K)