|

CERTAIN ASPECTS OF THE PROPOSED ESCALANTE NATIONAL MONUMENT IN SOUTHEASTERN UTAH

By Jesse L. Nusbaum,

Senior Archaeologist.

To those accustomed to motoring at will over improved

highways and nearly directly to most objectives, the canyon of the

Colorado River through Southeastern Utah and Northern Arizona will

always present a most formidable and appalling barrier.

Only within the last fifteen years has the Colorado

River been bridged for mechanized travel between Moab, Utah, closely

adjacent to the Colorado state line, and Needles, California -- a

crowflight distance of approximately 375 miles, but more than 800 miles

as measured by the Colorado River.

The first intervening bridge was the Navaho steel

truss on north and south Arizona-Utah Highway No. 89, which spans the

primary gorge of the Colorado River 467 feet above the mean water level.

Impoundment of the Colorado River by Boulder Dam on the Arizona-Nevada

line, provided in conjunction with Highways Nos. 93 and 466, a second

intervening crossing some 540 feet above the old free-flowing river

level.

The phenomenal growth of travel to Grand Canyon

National Park has resulted largely from development of high-standard

access highways and their extension to scenic vantage points on the

highly elevated North and South Rims.

By reason of convenient and comfortable access by

modern means and highly developed facilities and services for human kind

-- this deepest, most sharply broken and spectacular section of Colorado

River Canyon embraced within Grand Canyon National Park of Arizona has

become known to millions of visitors.

Northward and eastward thereof, in the Southeast

quarter of the State of Utah, the Colorado River and tributary drainage,

including Green and San Juan Rivers, have in conjunction with natural

forces, created an equally amazing and distinctive wonderland. This

includes highly colorful meandering inner canyon gorges, with bordering

terraces, flanked and surmounted by fantastic pilings of diversified

erosional land forms to near or remote canyon rims rising to 3,000 feet

or more above the river level. Commanding canyon rims on the east are

the forested and, much of the year, snow-clad La Sal and Abajo, or Blue,

Mountains of Utah rising more than 9,000 and 7,500 feet, respectively,

above the river level. To the south, lone Navaho Mountain, sacred alike

to the Navaho and Hopi Indians, dominates the horizon. Westward and

adjacent to the river gorge, the rugged Henry Mountains abruptly ascend

to 7,500 feet above the wide valley floor.

Naturally and logically, the question arises as to

why this great area of outstanding scenic resources has not become known

to the public generally. The simple and direct answer may be synthesized

in a simple word -- inaccessibility for there are no present roads

traversing the area from north to south or east to west.

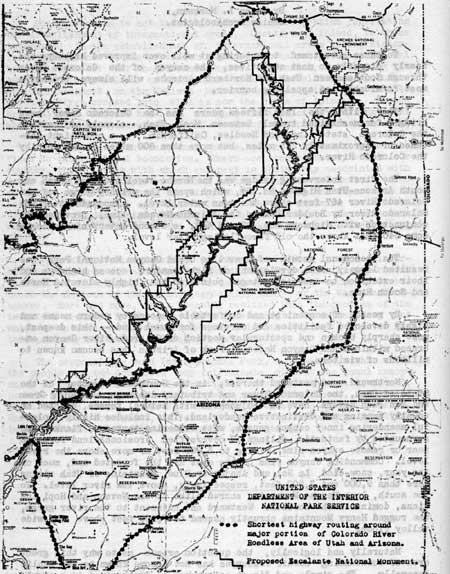

Map of proposed Escalante National Monument.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Recourse to road maps of Utah and Arizona will

promote understanding and realization of the immensity of this largest

roadless area in the continental United States. Generally referred to as

the Colorado River Roadless Area of Utah and Arizona, it has been

estimated that it comprises 8,890,000 acres, approximately 13,890 square

miles, after eliminating for a width of one mile to their ending, the

few entering roads that encroach to, or beyond, the first barrier of

this vast desert wilderness.

To encircle it by motor over the most direct highways

and unimproved desert and mountain roads, requires in excess of 750

miles of travel. Only for a few miles near the Moab, Utah, crossing of

the Colorado can one see from the valley floor the great

"Behind-the-Rocks" barrier wall of brownish red sandstone, gashed by the

Colorado River, which marks the beginning of the main Colorado River

Canyon and the northern boundary on the Colorado of the proposed

Escalante National Monument. At no other point on the great circuit can

one see, except remotely, any feature directly incorporated within the

approximately one-seventh portion or heart of this great roadless area,

which comprises 2,000 square miles of highest scenic values bordering

the Colorado, Green, and San Juan River Canyons in Utah, and constitutes

the proposed Escalante National Monument.

Northward from the confluence the area includes the

excessively entrenched meanders of Labryinth and Stillwater Canyons of

the Green River for an airline distance of 42 miles to influent San

Rafael River; the Canyon of the Colorado, for 33 miles, to its boxing

in, on the edge of Moab Valley; and the southern portion of the great

intervening plateau promontory, known locally as Great Flat and Gray's

Pasture, which separated the rivers. This area, from elevations

approximately 3,000 feet above the river levels, provides a

comprehensive scenic command of the northern and most highly colorful

half of the proposed Escalante Monument.

Southward from the confluence for a crowflight

distance of 120 miles the proposed monument area averaging 13 miles in

width, is more or less evenly balanced along the medial line of Colorado

River meanders, enlarging to embrace the outlying "Little Rockies" of

the Henry Mountains, and a greater width of deeply sculptured sandstone

ledge on the north side of influent San Juan River. Below the confluence

of the San Juan, the area includes only the west and north sides of the

Colorado River for an average distance of 5 miles to just below the

"Crossing of the Fathers", since the opposite side is incorporated

within the Navaho Indian Reservation.

Here at the "Crossing of the Fathers", in the closing

months of 1776, Father Escalante, courageous Franciscan Friar, and his

small band of followers, finally succeeded in descending to, and

crossing, the Colorado River as they returned half-starved and defeated

in their futile effort to open a trace from Santa Fe to Monterey on the

Pacific Coast. Former Superintendent Tillotson of Grand Canyon National

Park, who conducted and reported the initial survey of the Upper

Colorado River Canyon for the National Park Service, suggested the name

of Escalante for the much larger area then proposed to commemorate this

notable first crossing by white man of the Colorado River Canyon.

Fortunately for those who largely depend upon

mechanized transport, and that includes most of us, the Division of

Grazing of the Department of the Interior, in cooperation with the

Civilian Conservation Corps, has within the past two years,

progressively developed an entering truck trail from Highway No. 450

about 17 miles north of Moab to serve the interests of the few cattlemen

who graze stock atop the great wedge-shaped promontory between the Green

and Colorado Rivers.

Branching at the Knoll, about 22 miles west and south

of the highway connection, the left-hand truck trail continues southerly

approximately six miles to a terminus at Dead Horse Point. This is a

protruding and tapering finger of the great plateau which projects a

mile or more into the Colorado River Canyon beyond the great bays which

it separates, and ends in all but detached sheer-walled, butte-like

formations, perhaps a half mile in circumference at its top.

From the periphery of the rim of Dead Horse Point

which must be traversed on foot from the connecting neck, scenic command

is superb in all directions. About 70 miles of great Colorado River

Canyon are visible from this point. Seemingly to greet you, the Colorado

River swings northward to complete an entrenched hair-pin meander at the

very base of the abruptly towering 3,000 feet high formation on which

you stand. In no other area in America, to my knowledge, can one see so

vast an exposure of highly eroded red-bed formations, nor greater range

of reddish hues from deep maroons through to buffs. Shades of red are

favored colors. Plan to reach Dead Horse Point by three o'clock in the

afternoon and remain for sunset.

In the course of the past two years, it has been my

pleasure to conduct, or accompany, several hundred persons to Dead Horse

Point, and remotely from Mesa Verde and elsewhere, to stimulate visits

of an equally large number of national park and monument visitors. The

views of Colorado River Canyon from Dead Horse Point, alone, have

admittedly convinced even the most skeptical of the scenic merit of this

National Park Service proposal.

Landscape Architect Merel Sager of the National Park

Service, who was in charge of its second field investigating party, in

his report to Director Cammerer relating to the proposed Escalante

National Monument, stated that:

"The colorful canyons of the Colorado and Green

Rivers, without question, constitute the paramount landscape features in

the entire area, and their existence alone supplies sufficient

justification for the creation of a national park.

"In these days, it seems we hear more about the

recreational values of the national parks than we do about their

spiritual values. They are related, to be sure, but it is the potential

capacity of our national parks, with their inherent endowment, to supply

spiritual values which distinguish them from the multitude of other

recreational areas. The canyons of the Colorado possess this quality to

a marked degree, and for many reasons. There is color, glorious color;

200 miles of countless fantastic, weird monuments and pinnacles,

limitless in variety of form, slowly yielding to the relentless forces

of wind and water. Here is the Colorado, mysterious, treacherous,

forbidding; carving its meandering way through red sandstone canyons, so

rugged that they have thus far successfully defied east and west

commmutation of human kind in the whole of southeastern Utah. Here is

desolation., solitude and peace; bringing man once more to a vivid

realization of the great forces of nature. Yes, the canyons of the upper

Colorado have spiritual and emotional appeal equal to that supplied by

most of our national parks."

|