|

THE BIG BEND OF TEXAS

By Dr. Ross A. Maxwell,

Regional Geologist.

Te reach the Chisos Mountains in Texas by automobile,

one must travel 80 miles from Marathon, or approximately 110 miles from

Alpine, in the southwestern end of the state. A few miles south of

Marathon, pinkish-white and yellowish-white ridges will be seen on each

side of the road. These were laid down in a horizontal position in the

bottom of an ancient ocean that at one time covered that part of the

continent. After many years these rocks were folded into mountain

ranges, believed to have been formed contemporaneously with the

Appalachian Mountains. The rocks in these mountains were subjected to

weathering. The rain fell, the wind blew, and the rocks were broken up

and carried away by streams until only the roots of this mountain range

remained.

Many years later, during a period of the earth's

history that geologists call the Cretaceous, the sea again advanced over

this area and buried the old mountains under several hundred feet of

Cretaceous sediment. Since then, erosion has stripped away the

Cretaceous rocks, and again the roots of the old mountain chain are

exposed.

Continuing south from Marathon there is a mountain

range on the west side of State Highway 227 that extends from the

approximate latitude of Marathon on the north, southward across the Rio

Grande into Mexico. The northern half of the range is called the

Santiago Mountains, and the southern half, the Sierra del Carmen. Local

usage has popularized the term "Dead Horse Mountains" for the southern

half of the Texas portion of this range.

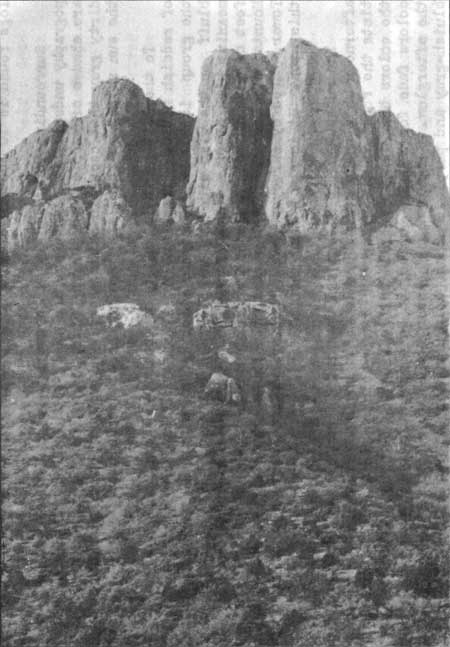

CASA GRANDE.

About 40 miles south of Marathon, the highway passes

through an opening in this mountain range; this is Persimmon Gap, the

entrance to the proposed Big Bend National Park. If you stop at the

highest point in Persimmon Gap and look around, you will see rocks that

were deposited during the same geologic era as those a few miles south

of Marathon. This is a second exposure of that ancient mountain range

that was formed millions of years ago. The upper walls in the gap are

formed of Cretaceous limestones and shales that were deposited in the

ocean which covered the old mountain range. As you pass from the gap the

largest group of mountains on the right is the Rosillos, so named

because of the roan color. Almost in front, but slightly to the right,

is the largest and highest mountain group in sight. These are the Chisos

Mountains, meaning "Ghost" or "Phantom" mountain. These rugged peaks are

the highest in the area and rise to approximately 8,000 feet above sea

level.

After leaving Persimmon Gap, the highway fellows

parallel to the Santiago Mountains (on left). If the car has been moving

at a normal rate of speed, you should soon see on the left a sharp

narrow canyon. This is Dog Canyon, or Bone Gap, and is the dividing

feature between the Santiago Mountains on the north and the Sierra del

Carmen (Dead Horse Mountains) on the south. It is about 200 foot deep

and averages 75 feet in width. A dim auto road turns off the highway to

it. On the west side of the mountain about two miles south of Dog Canyon

(left of highway) is another narrow canyon that averages 50 feet or more

in depth and in places is less than 10 foot in width. This is Devil's

Den, or Devil's Canon. You will soon be riding over a road where there

are several dips. These have been cut by streams that flow down the

western slope of the Sierra del Carmen. The running water is able to

carry a big load of rock debris down the mountain side, but when the

stream reaches the gentle slopes at the foot of the mountain, the load

is deposited. This surface that slopes from the mountain is virtually

all composed of rock fragments that have been washed from the tops of

the Sierra del Carmen.

A short distance farther there are a few exposures of

gray limestone. This stratified rock is the Boquillas flagstone. it was

deposited in the Cretaceous sea, and, with the materials that compose

the flagstone, there are thousands of fossil shells of oysters, clams,

snails, corals and sea urchins. These animals lived in the ocean and

when they died their shells fell to the bottom and were petrified in the

rock. Some of the fossil oyster shells are unusually large. It is not

uncommon to find them 18 inches in diameter. One fossil clam 49 inches

in length has been found.

When you have driven about 55 miles from Marathon,

the road will lead diagonally across a flattish area. This is Tornillo

Flat. The soil is very impervious to water. The rainfall soaks into the

upper few inches of the soil and makes a very sticky mud. When the water

dries, the mud cracks and breaks into little pellets. This area is the

desert of the Chisos country. During the dry season, there is little

vegetation except creosote bush and lechuguilla, but following a shower

the plants spring up as if by magic. In a few days they are in blossom

and the desert is clothed in a robe of gorgeous colors. This vegetation

lives for only a short time. Following the next shower, new and

different kinds of flowers appear. This procedure continues throughout

most of the year.

GIANT PETRIFIED CLAM.

In Tornillo Flat there are several sandstone hills

and ridges. In and around them are petrified logs and the bone fragments

of dinosaurs. The dinosaurs roamed over this country about 100 million

years ago. Some of the unfortunate monsters became stuck in the mud and

died. Their bones were covered with mud and water and were later

petrified. Weathering and erosion have uncovered the bones and we now

find them on the surface. Contemporaneous with the dinosaurs were

forests, and likewise some of the trees were petrified. Many fragments

of wood and some logs may be seen nearby. The largest of the logs found

is 10 feet in diameter.

Surrounding Tornillo Flat is a rough, hilly belt of

bad land topography underlain by sandstone and shale with brilliant

colors. There are shades of purple, red, brown, pink, white, black,

olive drab, and dirty gray that occur in bands sharply separated from

each other. As the sun shines on them, they remind one of the Painted

Desert.

To the left of the highway, southeast of Tornillo

Flat, is a belt of reddish hills. These are the McKinney Hills. The

highest peak in the group is Roy Peak, beyond which is a vertical

westward-facing bluff on the west side of the Sierra del Carmen. It is

Alto Relex, meaning high bluff. South of the Rio Grande is a vertical

cliff 2,000 feet or more in height that is a continuation of the Sierra

del Carmen Mountains, The small high peak at the top of the bluff is

called Shot Tower, used by surveyors when the various land surveys were

made of this area. It is now a land mark.

The sunset on the Sierra del Carmen is a gorgeous

sight. In the afternoon when there are wispy clouds in the western sky,

the sunlight tints the rocks in this range an orange-colored glow. As

the sun sets the colors brighten to a brilliant red. After the sun

disappears the colors fade for a brief period to be temporarily

brightened again by the afterglow. Eventually, however, the colors

change to pink, then bluish-gray and purple. These colors remain after

the light has disappeared from the other mountains, gradually fading

into the neutrality of twilight and then changing to the blackness of

night.

The highway continues across the flat to Tornillo

Creek, a broad dry wash, except after a rain, when it becomes a

treacherous torrent. A few miles farther the highway forks the loft fork

goes to Glenn Springs, Boquillas, San Vicente, Mariscal Canyon,

Johnson's Ranch, Castolon, and other points of interest along the Rio

Grande. Glenn Springs is the headquarters of a ranch, and is an

overnight stop for inspectors of the U. S. Immigration Service. Only a

few years ago, however, it was a thriving community. In 1918, when

Pancho Villa was active across the river, there were two companies of U.

S. soldiers stationed in Glenn Springs. When the trouble subsided all

but nine of the soldiers were withdrawn. Then, on the night of May 5,

1916, (Cinco de Mayo), a group of bandits from across the river

made the raid which is locally referred to as the Glenn Springs

massacre. Three American soldiers, a small boy whe lived there, and a

number of Mexican bandits were killed. The old adobe house that was used

as a fort, the store building, and several other houses still remain. In

some of them bullet holes can still be seen.

Boquillas, located on the Texas bank of the Rio

Grande, is occupying its third site. At one time it had a post office,

in days when the village marked the end of a stage line, and was a

stopping place for travelers from Mexico. Now there are less than half a

dozen homes, and only a few children to attend its public school. Though

seldom used as such, it is still a port of entry. The traveler wheo

stops there can be assured of an excellent meal in the isolated wayside

inn.

The head of Boquillas Canyon is a short distance down

the river from the village. This canyon was cut by the Rio Grande across

the Sierra del Carmen ranges. It is noted for its depth, narrowness, and

the sheerness of its walls. It was near the head of this canyon, in

1882, that Captain Charles Neville and his Texas Rangers came upon a

band of Indian raiders. The Rangers' ammunition supply was low and much

of what was left was used in firing at the Indians whe took to the

mountains without their horses. The rangers were traveling by boat. They

didn't want to leave the horses for the Indians te remount and ride in

further raids against the settlers. Ammunition was too valuable to be

used in killing the animals so the horses were blindfolded and knocked

in the head. Since that time some people have referred to this canyon as

the Dead Horse Canyon.

The right fork of the road, beyond Tornillo Crook,

leads to the Basin of the Chisos Mountains, whore the proposed Big Bend

National Park headquarters will be established. At this point the

speedometer should register 66 miles from Marathon. Here one can get a

good view of the Chisos. The farthermost peak on the east (left) side of

the Chisos is Nugent. The next one from left to right is Pummel, so

named because of its similar shape to the pummel of a saddle. The next

peak is Panther Peak, and the higher peak behind Panther is Lost Mine

Peak.

The big square-topped mountain in the gap to the

right of Lost Mine is Casa Grande (big house), and the large bluff on

the right side of the road is Pulliam Mountain. Near the road on the

left hand side is a mountain that stands away from the rest of the

Chisos group. This is Lone Mountain. About 6 miles farther the highway

passes the two ranch houses near Government Springs, from where there is

a good view of the Christmas Mountains. They lie 12 to 15 miles to the

northwest. The Paint Gap Hills, a low belt of red hills, lie about four

miles north of Government Springs. A short distance past the ranch

houses the road forks again. The right hand fork (Highway 227) goes to

Terlingua, a quicksilver mining district outside the park area.

Map of proposed Big Bend National Park.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Terlingua is a quaint Mexican village, where the

chief period of celebration is Cinco de Mayo, May 5, in

observance of the Mexicans' defeat of Maximilian. A few days before

this holiday, the houses, cemetery, and community center are decorated.

A baile (dance) is usually held and the villagers come in their best

costumes. The dance is at the community center, a small house with

outdoor concrete dance floor. Current for electric light is provided by

windchargers. The musical instruments are usually violin, guitar, and

harmonica. The baile may continue throughout the night. It frequently

extends into the following day and night. It is a gala occasion and very

few of the natives ever miss it.

The left hand fork goes to the heart of the Chisos

Mountains, through Green Gulch. Pulliam Mountain is on the right; a spur

of Lost Mine Peak is on the left, and Casa Grande, near the head of the

gulch. The road, although it may look level, is uphill all the way. Most

cars have to use second and low gears before they reach the top. When

you reach the top of the divide, and start down, you obtain the first

view of the Basin, a depression in the heart of the Chisos Mountains.

The floor of the Basin is approximately one mile above sea level. It is

completely surrounded by a mountain wall l,000 to 3,000 feet high. As

the road winds down to the headquarters area, whrre the CCC Camp is now

located, you may look through a gap in the mountain wall - the Window -

and see across the desert lands of the Big Bend, and on for miles into

Old Mexico.

The image of old Chief Alsate (Ol-set'-ee), legendary

Apache watcher of the Chisos, has been carved by nature in a volcanic

rock formation and can be seen from the mouth of Green Gulch, south of

Government Springs. Though lying on his back atop the massed remnants of

a boiling river of destruction, his head is elevated and he is facing

Lost Mine Peak. The local legend is that to find the "lost mine", one

must cross the Rio Grande into Mexico and there, opposite San Vicente,

Texas, in the early morning hours of Easter Sunday, stand in the doorway

of the ruins of San Vicente Presidio. As the sun rises over the Del

Carmen Mountains, at the back of the hopeful watcher, it is supposed to

shine directly into the mine's doorway, "somewhere" on Lost Mine

Peak.

From the Basin one may travel by horseback to the

South Rim of the Chisos Mountains. This rim has an elevation of more

than 7,000 feet and is approximately one mile above the Rio Grande, 16

miles to the south. From this point of vantage on a clear day, one may

see for a distance of at least 100 miles, a panoramic view of one of the

last frontiers and one of the finest in the Southwest.

|