|

STATUS QUO OF QUINTUS QUAIL

By Earl Jackson,

Custodian,

Montezuma Castle National Monument.

Quintus looked approvingly at his reflection in the

clear pool where he was taking his after sunrise drink of water. He

bobbed his head pertly as he saw the handsome black-helmeted face under

its jet plume as it gazed back, brighteyed, at him.

"Indeed I am quite a fellow." a mind reader might

have registered. "Here I am, eight months' old, full grown and in the

prime of young quailhood, able to lick any other saucy cock in the covey

- except maybe Papa --" as he looked discreetly over his shoulder at the

grizzled veteran who led the covey and fathered a good part of it. "And

I could lick Papa - if I wanted to badly enough. Ho hum. Glorious day!

Say, I like the looks of that girl --- !"

And so came the springtime of the year to Quintus,

scion of an honored family in the Southwest. He was related to almost

everybody of any consequence, it seemed. First were the other members of

his own species, Gambel's Quail (Lophortyx gambeli gambeli

Gambel), then the various other quail cousins, then the Bob Whites.

A little farther along the family tree came the wily partridges and

grouse, and finally the lordly turkeys. He wouldn't have cared much for

the turkeys, had he known of the relationship, for they would have

struck him as being high hat.

Of all these distinguished groups, however, Quintus'

people came first in importance in Arizona and many other parts of the

Southwest. For one thing they were the most numerous, and were found

widely distributed in Southern Arizona, Southern New Mexico,

Southeastern California, parts of Utah and Nevada, and all the way south

into Sinaloa, Mexico. One reason they were so numerous was that they

just naturally were family loving folks (Quintus was from just an

ordinary sized family of 14 children). They were widely distributed

because they could thrive in the hottest desert region and clear up into

the pine country at a mile and more above sea level.

But why worry about the family tree on a spring day.

Unless to make it grow some more! Quintus had just seen a girl who

looked awfully nice to him. He hurried over to make her acquaintance,

but it wasn't until the covey had left the water hole and was back up

the bank under the shelter of the gaunt looking mesquite bushes,

scratching for seed under some damp humus, that he was able to locate

her again.

She was one of the children of that family which had

joined the covey only yesterday. That was why he hadn't spied her

before. For that matter, a week ago he wouldn't have noticed her anyway.

That was February, and now it was March, the month in which quail of

Central Arizona's valleys begin sending love notes. It was a warm day,

so the covey remained active until nearly noon before taking a siesta,

in a spot where the wind wouldn't ruffle their feathers, and where they

could soak up the welcome sunshine and still be safe from marauders.

During the morning Quintus dexterously edged around until he was in

reach of the girl.

To you or me Quintessa would have looked just about

like any other feminine quail. She was a plain little thing, very sombre

hued by contrast with her admirer. But she had neat trim feet and legs,

a compactly feathered and sturdily built body, and carried her prim,

little head very alertly atop that gracefully slender neck.

Quintus approached to her side and offered her a

particularly nice looking mesquite bean he had found. She shyly ran away

a few steps, scarcely looking at him, and went on leisurely eating. He

came close again, neck carefully arched to just the right degree, plume

drooping a bit closer to the ground. She gazed at him with slight

interest, but seemed unworried about escape from his company. And so

they came together often during the next few weeks.

On a day early in April Quintus decided he couldn't

get along without Quintessa, and that if he didn't lay permanent claim

to her company, somebody else would. For instance, he didn't like the

way that fellow Braggar had been looking at her. His formal offer of

marriage had none of the knee bending of Victorian romances, nor of the

conciseness and brevity of modern swains, but was rather the stately

gesture of a proud gentleman who offers what he knows is an honorable

role to an equal. His sideward semi-circular prancing step in front of

her said, "Lady of my heart, will you be my wife?" and when he spread

the feathers of both wings and dragged the wing tips in the dust it

said, "You couldn't make a better choice."

Quintessa looked gravely at him, and was about to

answer, when she heard a flurry of motion a few feet away. And who

should rapidly stride to her, right in front of the infuriated Quintus,

but Braggar, that swaggering fellow who was never very far away! Quintus

launched himself plummet-like at the intruder, and Braggar met him head

on in a flutter of beating wings. There followed a battle royal, in

which each contestant grimly strove to knock the other over, and make

him retreat. Time and again they lunged at each other to stand chest to

chest, each with his head over the other's shoulders. A casual glance

might have misled an onlooker into thinking here was an exhibition of

brotherly love, but a closer look would have revealed that those

exhausted game cocks were trying, each on his own, to gouge with his

sharp beak a hole in the other's back. Feathers flew, and blood stains

spread onto their faces. Completely spent, they would rest a few seconds

at a time, then withdraw to lunge again into that terrible test of nerve

and strength.

Quintessa thought all this highly interesting, and

she stood at ease, head half cocked to one side, admiring the

proceedings, although from time to time she would lower her head to eat

some pleasing tidbit. Although she had been Quintus' girl friend for

several weeks, she placidly accepted the thought that she would be the

wife of the winner, whichever it was. And if Quintus lost, he might not

find a wife at all that season.

The battle raged, between rest periods, for nearly

half an hour, but at the end of that time, Braggar decided he had

enough, so he beat a rapid retreat, leaving some of his back feathers.

And Quintus sick, bloody, and weak, nearer dead than alive, returned to

Quintessa. There was no question now about her. For as soon as he had

rested she indicated, "Hadn't we better start looking for a house?"

They spent part of that day, and several more days of

honeymoon, hunting about for a suitable nesting site, returning between

times to visit with other members of the covey. After a few days,

however, their friends were practically forgotten in the intensity of

their search for a desirable location. At last they found the perfect

spot. There was soft earth, surrounded on three sides by tall grass,

underneath a spreading algerita bush which sent its upper branches into

a huge mesquite.

Quintessa busily scratched away in the loose earth

until she had dug a hollow about an inch and a half deep, six or seven

inches across. Then began the task of nest building, a job which was to

spread over several days. Quintus, while giving lots of moral support

and occasionally carrying a twig, was about as useful on this job as a

bull in a china closet. Quintessa did most of the work of selecting

leaves, stems of grass, pieces of dried weeds and small sticks, and laid

them into the loosely knit nest.

Finally the nest was finished, so that it slightly

overlapped the edges of the hollow, and she patiently settled herself

one day to prepare for motherhood. Quintus now knew what his job was to

be. He set himself up as a committee of one to guard that nest, and

spent the waiting hours in patrolling and feeding within a radius of 25

to 75 feet of the spot.

The eggs were of a buffy white color, spotted with

irregular splotches of dark reddish brown markings, so perfectly

camouflaged as to be almost invisible. Quintessa laid an egg a day for

six days, and then evidently decided it was the Sabbath, for she rested

one day. Then back to work she went for a five-day shift, a day of rest,

and one final laying period which brought the egg total to sixteen.

One day a lean and wicked looking house cat came

slinking toward the nest. Quintus' keen eyes caught sight of the

intruder before it saw him, and he didn't waste any time. He darted to

within about four feet of the enemy, so it would notice him, and then

began edging away from the direction of the nest. The cat looked at him

for a split second, made as if to pounce at him, but on seeing the bird

move away, prepared to stalk its prey. Then Quintus went into an act.

While moving away from the vicinity of the nest he staggered drunkenly

along, one leg buckling under him every few steps, as though it was

injured, while his wings did a dramatic and helpless sort of fluttering.

For a hundred feet and more he forced himself to hobble in this manner,

just barely out of reach of the cat. Then he took to his wings and flew

out of danger in a circular route. Two minutes later he was quietly

walking back toward the nest from the opposite direction.

He arrived within calling distance just in time to

hear Quintossa's low call informing him she was ready for her

mid-morning rest and feeding period. He waited some distance from the

nest while she stretched and fluffed her feathers before joining him.

They fed together for over an hour before she returned to her eggs. That

afternoon her feeding period lasted for nearly two hours for the day was

warm, and the eggs held enough heat to prevent chilling.

While Quintessa was absent one afternoon, a large rat

stole from his nearby burrow and carried off an egg to his den. He

enjoyed his meal so much that he returned on the following day.

Quintessa caught him halfway to his hole, and her furious beating wings

and sharp beak caused him to drop his burden and flee. The egg was

cracked, and she didn't know how to move it back to the nest, so while

she returned to setting on the other eggs, the ants proceeded to enter

the cracked egg and thoroughly clean out its contents. They were such

voracious creatures that sometimes they were known to invade a nest,

especially when chicks were beginning to hatch, killing then and

occasionally even the mother.

Of the fourteen remaining eggs, the first one pipped

on the morning of the 22nd day. And while we leave Papa to his lonesome

sentry duty, and while Mama is half dozing, let's take a look at that

first chick. He is in a tight spot, and he knows it. Squirm and wiggle

as he will, he can make no headway in any direction. The place is as

black as the inside of the proverbial black cat, and the air is not fit

to breathe.

He begins with desperate violence to force the rough

spot on the upper tip of his bill against the smooth hard wall around

him. Soon the wall breaks through in a tiny spot. The younster rests a

few seconds, but he has the characteristic vigor of his kind, and soon

gets busy forcing his way again, gradually turning his head and body

around as he does so. When he has cut a circle almost completely around

the inside of the shell at its large end he shoves upward, and the top

swings open like a door, still hinged by the soft inner membrane at one

place. A few minutes later he sticks his head out. It is still quite

dark, but now he can breathe easily, and so he loses no time clambering

out of the shell. He scrambles restlessly over the other thirteen eggs

until he approaches the edge of the nest, where he pokes his head

through two of his mother's feathers for the first look at the light of

day.

Thus a blessed event came to be. And others were not

long in following. Things were happening thick and fast, for brothers

and sisters were pipping shells rapidly now and popping their heads out

in all directions, like popcorn in a skillet. Within two hours a dozen

youngsters were hatched and were seething with energy. The other two

eggs were pipped, but not hatched.

If a scientist had then happened by with a friend,

and could have seen these newly hatched youngsters, thickly covered with

down, with wings nearly feathered, he might have embarrassed Quintessa

with his comment. He perhaps would have said to his friend, "Now here's

an example of wh t I was talking about. Birds that are higher in the

scale of evolution such as crows, thrushes, and the like, are hatched

nearly naked and almost entirely helpless. These lower in the scale,

such as quail, are ready to run as soon as they come out of the egg, and

within a few days they start flapping their wings.

Quintessa however, didn't hear any such comments and

so she peacefully took permanent leave of her nest, the twelve

youngsters following. The two pipped eggs were left behind. A heartless

proceeding, you think? But Nature's children must do that to survive.

Even if she had waited for the two unhatched youngsters, they would have

been weak and handicapped from the beginning, and would have fallen prey

to enemies, besides hapering the progress of the others.

Quintus, like most fathers, had been more or less

left out of the proceedings; but now he proudly followed the last of the

toddlers. When Quintessa stopped to give the children a rest, he

withdrew a short distance and perched in a bush where he could watch for

possible enemies. His responsibilties were only started. His wife was

the hub of a little universe now, and it took all her thoughts to teach

and discipline the young. He was the guardian of them all. On familiar

ground he would let Quintessa lead the way with the babies, but in

strange or dangerous spots, he led the way himself.

Within two days the chicks were hungrily chasing

insects, living almost entirely on a meat diet, although a little later

they would expand their bill of fare to include green weed shoots and

buds, parts of flowers, seeds, and tender leaves. The family moved

around a lot, but never went any great distance. It was unlikely that

any of them in a lifetime would move more than a mile or two away from

the place of birth, unless disturbed by hunters.

Midsummer came, and the chicks were now easily able

to fly to roost with their parents in the low thick hackberry trees

along the creek bank. In the daytime they investigated everything. One

became the victim of a wary rattlesnake which had missed the alert eyes

of Quintus. And a Cooper Hawk darted from a low hiding spot one day as

they went down to get water at the creek edge. Thus another youngster

that was not quick enough to hide, lost his life.

While Quintus on many occasions saved the lives of

members of his family, it was impossible to keep them all out of harm's

way. This family was meeting the typical fate of the quail tribe. That's

why so many youngsters were born. One night when the family was at roost

in a hackberry, a house cat got into the tree. Quintus couldn't see a

thing in the darkness, but as the cat grabbed him he awoke and let out

his warning call, at the same time twisting loose from the tearing claws

to fall to the ground, minus some feathers and some blood from torn

flesh. The others scattered to earth in confusion, but not before the

cat had one bird.

Late July found Quintus and Quintessa with nine husky

adolescents on their hands, youngsters half grown and practically able

to fend for themselves, except that they had a lot to learn. By now

Quintus had as big a part in educating and discipliing them as had their

mother.

It was about this time that one day they heard the

plaintive crying of three little fellows who belonged to a neighbor's

family. Some disaster had scattered the rest of their family, and they

were lost. With characteristic generosity, Quintus and his wife adopted

these waifs as their own, and they shared all the privileges of the

other children. This generosity among quail has for many years caused

people to have the mistaken belief that the birds raise two broods of

young each year, simply because they had young of two different

ages.

Through August the family lived in luxury. There were

plenty of grasshoppers, and if there is anything a quail likes more than

a few grasshoppers it is a larger supply of them. They ate more of these

insects than any other, although a large variety of bugs fell prey to

their appetites. Mosquite beans were also a highly desirable food item.

The pods were too tough to tear open, but after animals had eaten them

and the undigested beans had passed on, the quail found them to their

taste.

In mid September it would have required close study

to figure out which were the parents and which the children, for the

youngsters were full grown, and they thought they knew more than their

parents. This opinion was not shared by the elders, and stern

disciplinary action was often necessary. Quintus was determined that he

should wear the pants in his family as long as he was around. Yet, on

the whole, they all get along pretty well together, and did a great deal

of peaceful talking among themselves.

Quintus still stood guard a good part of the time

while the family fed, and if a shadow of a hawk soared overhead he would

issue his warning call, the extent of warning depending on the proximity

of the menace. If he wasn't much alarmed, a few of the children would

flutter or fly clumsily to protection, and the others would slowly

straggle after them. But if there was real danger they didn't lose time

in taking to wing.

You never saw more sociable folks than these quail.

While they fed, there would appear to be no end of petty squabbling and

bickering. But it was no more than the interchange usually noted in some

feminine gatherings among the human species. And in the evenings, after

they had leisurely made their way to roost, they would sometimes engage

in exchanging comments, half of them talking at once, for a long time

after dusk. You could never imagine how they found so many interesting

things to discuss in those low voiced conversations, but anybody who has

ever passed a quail roost in late evening is familiar with the

sounds.

October faded into late autumn. The grasshoppers

began dying off, and there was a lull between growing seasons. The

family now had to feed largely on seeds that had been left over from the

summer, and so they did a great deal of scratching around in the litter

under bushes, as chickens do. Life was very tranquil until suddenly one

day quail season opened. A terror-filled two weeks followed. Quintus and

Quintessa had been unable to inform the children of how to take care of

themselves when confronted with the thunder of big shotguns, and the

only recourse was added watchfulness. On several occasions, however,

they were surprised, and two of the children fell with their bodies

riddled with shot. A third bird, with a broken wing, was eaten by a

coyote.

Quintus learned what it felt like to have a round

ball of hot lead bury itself in his chest, and the fevered agony of

tortured muscles around that irritation bothered him for many days.

Finally, however, his body healed, although he would carry that lead

shot as a reminder for the rest of his life.

Ultimately the hunting season was over. The cold dry

weather of early December made it a hard job to find sufficient food at

times, so the covey had to cover more and more ground each day to get

enough to eat. In coldest weather the birds didn't spend as many hours

feeding as they had earlier in the season, but they were also a little

less active, hence used somewhat less body energy.

The end of the year brought rains and moisture-filled

soil. Winter plants began popping their tender stems above the soil in

the open sunshiny spots. When Quintus led his covey into the open spaces

to feed on these delicious green shoots, he found other coveys had taken

to the same idea. So there began a flocking of coveys, and a great deal

of squabbling arose between heads of different families, for each cock

wanted to rule the roost.

Quintus had to defend his prestige against other

fathers on various occasions, so the result was he ran around with a

sore back a good part of the time. As January and February rolled into

early March the fifty odd birds, representing a half dozen coveys, began

feeling the impulses that come with Spring. Rivalry started between the

cocks.

Quintus didn't know he was a back number with the

younger generation until one day, shortly before the time for the flock

to begin breaking up as birds began pairing off to hunt for nesting

sites, he was feeding near to a young lady who was designated to cause

heart palpitation among young swains. A sturdy young fellow, spying the

two, decided Quintus was being too friendly to the apple of his eye, and

came hurriedly over to discourage the acquaintance.

Quintus, out of habit, administered a disciplinary

peck at the head of the young cock, expecting the youngster to back

away. He did - about two steps, and then launched himself headlong at

Quintus. And Quintus, startled, recognized one of his own boys! He was

almost completely bowled over by that first rush, but then recovered his

equilibrium and parental wrath at such disrespect, and dived into the

fray. It didn't take him more than a minute to realize that here was a

foeman worthy of his mettle. He would not have gambled on the outcome,

although he had never been beaten. Possible embarrassment was saved for

him by the timely shadow of a circling raven, which caused a general

retreat to the shelter of the bushes and an end to the hostilities.

A few moments later Quintus saw the impetuous

youngster happily showing some choice seeds to the young lady who had

been the subject of the argument. Somehow he felt a little old, as he

perched on a rock to survey the flock. He thought, "I must be getting

old, when my own boys decide to put the old man on the shelf. Guess I'm

a has been." That was a terrible thought. "No, by heck! I'll show 'em!

I'll raise another family, I will! Bigger than the last one!"

He dashed off at once to find Quintessa. She was

never far away. She was so used to being bossed by him that she just

naturally stayed fairly close. He burst out without delay into rapid

talk. "Come, Quintessa, it is time for us to look for a nest. Hurry!"

She cocked her head to one side and looked at him. "Dear Me, Quintus.

Must it be so soon? Haven't you forgotten something?" He was taken

aback. "Forgotten what?" She was very demure. Quintus realized he had

almost forgotten how attractive she was. "Well---I ---- there was a time

----. You know, I just love a nice fat mesquite bean once in a while, or

a choice beetle --. You must give a girl a chance to make up her

mind."

Quintus was dumfounded. But it didn't take him long

to get the point. And so he dashed off into the bushes to hunt for the

tenderest, juiciest morsel he could find, with which to tempt the lady

fair.

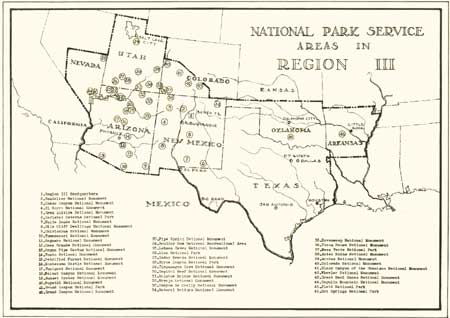

National Park Service Areas in Region III.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|