|

THE NATCHEZ TRACE - AN HISTORICAL PARKWAY

By Malcolm Gardner,

Acting Superintendent,

Natchez Trace Parkway Project,

Jackson, Mississippi.

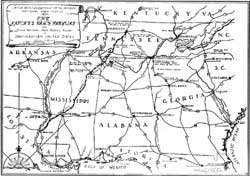

MAP OF THE NATCHEZ TRACE PARKWAY

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

When the white man began his exploration of what is

now the southern United States, he found ready-made for his travels a

network of Indian paths linking village with village and tribe with

tribe. These trails showed a marked tendency to follow watershed divides

in an effort to avoid stream crossings and swamps, in spite of the

circuitous windings of such routes. Several of these trails, though

individually not of outstanding importance, when joined together led in

a northeasterly direction from the present city of Natchez, in

southwestern Mississippi, to the Middle Tennessee country. Thus the

component parts linked the important tribes of the Natchez, Choctaws,

and Chickasaws. Toward the north, the trail touched the western claims

of the Cherokees. This route gradually increasing in importance became

known to later history as the Natchez Trace. That a few of these

Southern trails became much more important than other paths through the

forest was due to the military, political and commercial activities of

white men pushing north from the Gulf of Mexico and west from the

Atlantic.

By about 1716 the French had a trading post and a

fort, Rosalie aux Natchez, high on the bluffs of the Mississippi and

dominating the Natchez Indians. Plantations and a settlement followed

closely. The massacre of the garrison and settlers at Fort Rosalie by

the Natchez in 1729 led to the dispersion and virtual destruction of

this tribe, whose complicated social structure and religious ceremonies

have been described in considerable detail by amazed French observers

and still constitute a fascinating story for historian, anthropologist,

and Sunday supplement reader alike.

Of greater importance than the Natchez in the story

of French colonial expansion in the Mississippi Valley were the

pro-French Choctaws and the pro-British Chickasaws. Here the world-wide

struggle of France and England for imperial dominion was fought out on a

small scale as colonial officials and Indian traders guided the war-like

predilections of their red allies. When a remnant of the hunted Natchez

fled through hostile Choctaw territory to take refuge with the

Chickasaws, Lemoyne de Bienville, Governor of Louisiana, set his

energies toward completing French revenge on the Natchez and crushing

the Chickasaws, and doing both with one blow at the center of the

Chickasaw power. Their villages were concentrated in a prairie section

still called the Chickasaw Old Fields in present-day northeastern

Mississippi. While Bienville gathered his French militia and Choctaw

tribesmen, Pierre d'Artaguette, commandant at the Illinois posts,

marched south with four hundred men, two-thirds of them Indians, to

effect a junction with Bienville. The two forces were never joined, but

defeated in detail within a week of each other in May 1736. Bienville

reported that English traders aided in repulsing him before the

fortified village of Ackia. The defeat was a blow to French prestige,

and France never attained to complete domination over the territory

between the Mississippi and the Appalachians.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century the

Spanish came into possession of much of France's territory in the

Mississippi valley. England held the Natchez district from 1763 until

ousted by the Spanish in 1779, while the young United States succeeded

to English claims along the Mississippi at the close of the American

Revolution. Two outposts of these conflicting forces were Natchez, a

northern center of Spanish power in the lower valley, and Nashville, the

western spearhead of settlement of the new American Republic. Five

hundred miles of wilderness separated these two settlements, but the

common economic interests of the Mississippi valley attracted them

toward each other. The link by land between the two points was the

Natchez Trace which traversed parts of the present States of

Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee. It was used extensively by

frontiersmen returning home after having floated their produce down to

New Orleans. With American occupation in 1798 of the Natchez district,

long in dispute between Spain and the United States, Natchez assumed a

new importance in American eyes as a step toward the domination of the

Mississippi valley, and added importance was attached to the Natchez

Trace as a military and political line of communication with this

southwestern outpost of the republic.

A post road was established early in 1800, and--as

the Post master General complained--"at a great expense to the public on

account of the badness of the road which is said to be no other than an

Indian footpath very devious and narrow." He suggested to the Secretary

of War that United States troops stationed in the southwest might

advantageously be used "in clearing out a waggon-road and in bridging

the creeks and cause-waying the swamps between Nashville and Natchez."

Late in 1801 treaties were negotiated with the Chickasaws and Choctaws

by which they agreed to the improvement of the route.

General James Wilkinson, commanding the United States

army in the West and one of the commissioners for treating with the

Indians, immediately prepared a map of the Natchez Trace and closed his

description of the survey with the statement: "This road being completed

I shall consider our Southern extremity secured the Indians in that

quarter at our feet and the adjacent Province laid open to us." He made

one important change in the old trail by moving the crossing of the

Tennessee River from Bear Creek to Colbert's Creek, several miles up the

river.

Early in 1802 the troops were at work on the road

through the Indian country, the boundaries of which were the Duck River

Ridge, 30 miles south of Nashville, and Grindstone Ford on the Bayou

Pierre to the north of Natchez. The acquisition of Louisiana and the

establishment of New Orleans as the territorial seat of government

increased the need for better postal communication with that city. In

1806 a Congressional appropriation of $6,000 was made for the

improvement of this route under the direction of the Postmaster

General.

Francois André Michaux, scientist and western

traveler, wrote that the work of the army had shortened the route from

Nashville to Natchez by 100 miles. The Postmaster General estimated that

the survey to be followed in the new improvements would reduce the

distance by 50 miles more. Thus the less directional of the ridges were

abandoned, and the distance was shortened by bridges and causeways to

expedite communication and the passage of the mails. Like a stream with

an increased current, this road cut new channels for the volume of its

traffic, but still it remained the Natchez to Nashville road, the

Natchez Trace.

SECTION OF PARKWAY NEAR NATCHEZ

Along this road passed pack horses and Kentucky

boatmen; outlaws lay in wait for the unwary traveler; and a few early

tourists such as Francis Baily and Dr. Rush Nutt vividly described the

hardships of the journey. A few inns, or stands as they were usually

termed, were opened to care for travelers along the Trace. At Grinder's

Stand Meriwether Lewis met his death in 1809. Early in 1813 after his

Tennessee militia was ordered disbanded at Fort Dearborn, near Natchez

Andrew Jackson moved these troops north over the Trace and earned the

devotion of his men and the sobriquet of Old Hickory by his untiring

attention to their needs during the hardships of this winter march. In

1814 reenforcements for Jackson at New Orleans came south over the

Trace, and a considerable part of the victorious army returned to

Tennessee over the same route. In 1816 both the Choctaws and Chickasaws

relinquished lands in the Mississippi Territory. Settlers from the older

settled areas on the north and east poured into the newly opened lands,

and the pressure of these newcomers wrung additional territorial

concessions from the Indians. In 1820 by the Treaty of Doak's Stand, at

the old Choctaw Agency on the Natchez Trace, the Choctaws surrendered

more territory, and finally in 1830 at Dancing Rabbit Creek they

surrendered the remainder of their lands east of the Mississippi. Two

years later at Pontotoc Creek the Chickasaws agreed to cede their lands

and move west of the river.

As the population had grown and new settlements had

sprung up, additional roads were required and traffic was diverted into

new channels. Jackson's Military Road, Gaines' Trace, the Boliver Trail,

a southern route through Georgia, and a number of others were cut

through the forests and causewayed over swamps. The development and

improvement of the steamboat, however, gave the main blow to most land

travel for long distances. The Natchez Trace lost its importance as a

through route; sections of it were abandoned while other parts became

neighborhood roads and links between small settlements, as was the case

before the white man's coming. The cycle had swung a full turn.

The significance of the Natchez Trace lay in the

political, military and economic importance of the two towns of Natchez

and Nashville at the close of the eighteenth century and in the opening

years of the nineteenth. Perhaps the importance of these two places was

the accidental result of a temporary stalemate of conflicting forces in

the Mississippi Valley -- French and British, Spanish and American,

Indian and White -- but the Trace came nearest to a practicable

all-weather route without requiring the construction of large numbers of

expensive bridges and causeways. It served, therefore, as an avenue of

American expansion in the old Southwest. To date no evidence has been

revealed to show that it was not the first national road, the first of

internal improvements resulting from support with the material resources

of the central government and with direct appropriations by

Congress.

The above outline of the history of the Natchez Trace

and of some of the events occuring in its vicinity is a very brief

summary of the results of an extensive research project conducted on

this subject. The procedure in securing documentary materials followed

the conventional practices advocated in the academic seminar. Official

documents of the United States and of Tennessee, Alabama, and

Mississippi, manuscripts as well as publications, were examined, and

some of the most interesting material came from the unpublished records

of the War Department, the Office of Indian Affairs, and the Post Office

Department. In the Library of Congress the Manuscript Division, the Map

Division, the Rare Book Room and the Local History Section all offered

considerable material. Among several maps secured from the files of the

War Department was General Wilkinson's survey of the Natchez Trace. From

the General Land Office came the township plats of the early rectangular

surveys, scaled two inches to the mile and showing the Natchez to

Nashville road and adjacent sites through most of its three hundred mile

length in Mississippi. In many cases the field notes of the surveys

accompanied the plats. Two unpublished maps showing in detail the

location of certain Chickasaw villages were secured from the French

national archives. Such was the type of material from which was written

the story of the Trace and its associations.

The story of a place or an event is one thing; its

exact geographical location is still another matter. The problem of

locating on the ground the route of the old Natchez Trace and the sites

of adjacent points of historical interest involved to a considerable

extent certain technical skills. Map scales had to be translated from

leagues and toises to miles and rods and then applied to a conjectural

location on the actual ground. Map indications of streams, trails,

prairies, and hill contours required hypothetical identification with

the originals and the verification of other maps and then correlation

with any available written descriptions. The map makers of the

eighteenth century were not marked by that passion for accuracy which

characterizes the technical work of our present mechanical age. Even on

the large scale survey plats of the 1830's and 1840's the field

investigator would be forced occasionally to disregard the evidence of

the map as interpreted by its compass points. If the map indicated a

road running southeasterly while a study of the ground showed a usable

ridge running south by southeast with very rough and broken country

stretching out on either side, then the judgment of common sense

dictated the decision that the old road followed such a ridge. The

evidence of the map had perforce to be abandoned.

While the general route of the Natchez Trace was well

known, considerable uncertainty existed as to its exact location in a

number of places. In the work of field location consideration was given

therefore to all available evidence -- documentary materials, maps,

survey plats and notes, local tradition, and physical remains or road

scars in the ground. Certain places which could be easily located along

the old road as stream crossings, important sites, and intersections

with township lines, were used as control points and the work of

location carried on in detail between them. The township plats of the

Congressional or rectangular survey were basic data in most of

Mississippi and Alabama. In the Old Natchez District in southwestern

Mississippi and in Tennessee the random land grant system prevailed, and

a considerable amount of location was based on such local records as old

deeds and land surveys, which might mention the Natchez Trace or the

Road to Nashville or the Post Road as a property line for adjacent

lands. The minutes of a county court concerning repairs or relocations

sometimes gave information about the early location of the road. One

apparent contradiction in its location as shown on the maps was solved,

after field study, as being a route along a roundabout ridge for wet

weather, but with a short cut through the bottoms for dry weather. And

of course certain of these differences represented changes in its route

as time passed. As finally flagged on the ground, the location of the

Trace includes for the most part the revisions of 1806 and after, since

these improvements constitute the route appearing on later maps and

particularly on the survey plats.

Congress has authorized the construction of a parkway

along the general route of the old Natchez Trace, designed for tourist

and passenger car traffic. Presumably the Natchez Trace Parkway

eventually will be one section of a national parkway system of arterial

routes for passenger cars. A parkway is an elongated park containing a

road, and a parkway as a part of a comprehensive recreation and

conservation program would make available to the traveler certain areas

along its route of a scenic, scientific, and historical importance. On

the Natchez Trace Parkway historical features will be emphasized

although final plans for preservation and development are far from

complete.

In the first place this parkway itself is a

memorialization of the old Natchez Trace and bears its name although

technical standards required for modern traffic do not allow it to

follow closely all the crooks and turns and some of the narrow ridges of

the old road. Plans are now being made, however, for the preservation of

a 10-mile stretch of the old Trace. In the loess soil in south eastern

Mississippi the effect of considerable traffic combined with gradual

erosion had cut the old roadbed deep into the ridges on which it runs.

So slow has this process been that the steep banks on either side have

been stabilized to depths of 10 and 15 feet by the roots of small

vegetation. Overhead the tree branches form a high arch. So narrow are

some of these sections that vehicles could not pass each other. It may

be asked whether this is history or landscaping, and the question may be

answered by saying that the preservation of such a section of the Trace

is a charming re-creation of the old road and of its historical

atmosphere*.

Toward the Natchez end of the Parkway is the

Selsertown Mound of unique formation and probably constructed by

prehistoric occupants of that area, but showing evidence of later

Natchez occupation. Within three miles of Natchez are the Natchez

Indians. These areas seem worthy of inclusion within the parkway lands

and of preservation for archeological study at some future time --

perhaps 10 years, perhaps 100 -- when their artifacts may be displayed

and the history of their builders related with suitable museum

facilities, since much of the social and economic history of a people is

explained by the objects used in their daily lives. Two hundred and

fifty miles north of the Natchez lay the center of Chickasaw power.

Congress already has authorized the Ackia Battleground National

Monument. This is the proper place to present the history of that

nation, and there is much more to Chickasaw history than a recital of

tribal wars and white aggressions. The anthropologist and the

archeologist are also historians, and the present-day techniques of

museum display will allow a presentation of historical material with a

high degree of scientific as well as popular interest.

The white settlement of the old Southwest offers some

interesting possibilities in the presentation of historical material.

Fifteen miles east of Natchez stands an unpretentious farm house, known

as Mound Plantation. The earliest part of the building was constructed

about 1790 by a Scotsmen unknown to fame, who had obtained a Spanish

land grant of some 600 acres. The house served as an inn along the

Trace; gradually slave quarters, an overseer's house, and a guest house

were added to the plantation messuage. The house has no architectural

merit. It is as undistinguished as its builder. Yet it and its first

owner well represent the common people who came into this newly opened

country seeking to exploit the land, to acquire slaves and lands and

houses and still more slaves and more lands. This was the southwestern

agricultural frontier where cotton became king and gentry was created,

in one generation. Also in and around Natchez is another and later style

of architecture, graceful and delightful, highly ornamental, and

expensive to maintain in the social station to which it was accustomed.

This was mainly Greek Revival form, with occasional French and Spanish

influences, and in its parlors and drawing rooms presided a ruling

class. All this, too, is American history. The interpretations of the

architect may well rank him also as an historian.

The history of the Natchez Trace, of the sites along

its route, of the cultural and economic tides flowing through the

country it served, would seem a proper concern of the national

government and of its citizens. Such a story transcends the narrow

bounds of politics and warfare, and deals with a variety of man's

activities. With the disciplines of the anthropologist, archeologist,

and archeologist, and architect as an aid and with the skill of the

museum technician for the preparation of visual interpretations, history

has an interest and a message for all classes of people.

|