|

THE SHARK RIVER WILDERNESS OF THE EVERGLADES

By Daniel B. Beard,

Wildlife Division

Washington

[Editor's Note: The proposed Everglades National Park

in southern Florida will be the largest Service area east of the

Rockies. It consists of 1,454,092 acres and is exceeded in size only by

Katmai National Monument in Alaska, Yellowstone and Mt. McKinley

National Parks, and the Boulder Dam National Recreational Area. The

western coast of the Everglades seldom is visited by anyone because it

can be approached only by water. The writer of the accompanying article

describes a trip to a remote section of the proposed park in order that

Service employees may be better acquainted with the general character of

that unique project.]

(click on map for an enlargement in a new window)

|

When John James Audubon saw Florida in the 1830's his

first impressions were not the type that a Chamber of Commerce might

pounce upon as being useful utterances of a visiting celebrity. He

wrote: "Here I am in Florida, thought I, a country that received its

name from the odours wafted from the orange groves . . . and which from

my childhood I have consecrated in my imagination as a garden of the

United States. A garden, where all that is not mud, mud, mud, is sand,

sand, sand; where the fruit is so sour that it is not eatable and where

in place of singing birds and golden fishes, you have a species of ibis

that you cannot get when you have shot it, and alligators, snakes and

scorpions."

Anyone who has penetrated the remote areas of the

state is likely to agree with Audubon at first. The second impression is

more favorable however, when the star dust of tourist propaganda is

rudely cast aside and familiarity with the country reorients one's sense

of values. Again referring to Audubon, we find that he too gets into a

more tranquil mood after becoming acclimated. Speaking of a section of

the proposed Everglades National Park, he says: "The flocks of birds

that covered the shelly beaches, and those hovering overhead, so

astonished us that we could not for awhile open our eyes. . .

Rose-coloured Curlews stalked gracefully beneath the mangroves. Purple

herons rose at almost every step we took, and each cactus supported the

nest of a White Ibis."

Many of us got our first impression of the

Everglades, I am sure, from a picture someone once made called "The

Mysterious Everglades," and which someone else put into a geography

book. It showed a giant tree festooned with lianas, standing on the bank

of a river. Behind the tree grew a dense, tropical jungle with parrots

flying through it. In the river was a miscellaneous assortment of

herons, ibises, egrets, alligators, turtles, and what not, while off in

the background, the artist threw in a dozen or so flamingos for good

measure. The ludicrous picture made an impression on many little boys

and girls who never realized that Everglades meant exactly that --- ever

glades. Childhood ideas often stick with us, so it is with surprise and

some dismay that many people get their first look at the Everglades

prairies stretching off many dreary miles on both sides of the Tamiami

Trail.

The Shark River section of the southwestern part of

the proposed Everglades National Park is a remote area, difficult of

access, and embodies the true wilderness of the southern Everglades. The

easiest way to describe the country is to recount a trip there in an

accepted travelogue manner.

Soon after midnight, we left the stilt houses of

commercial fishermen clustered behind Pavilion Key in the Ten Thousand

Islands region. A fresh southerly breeze raised gentle swells on the

Gulf of Mexico as we steered a southeast course in the deep water along

the edge of the shoals. All the rest of the night and until well into

the morning, the shoreline of the western coast of the proposed

Everglades National Park could be discerned off to port. It was just a

thin streak separating sky from Gulf with some Australian pines that had

been planted on Wood Key as the only landmark to identify our position.

How the pilot knew when to swing toward shore is a mystery that remains

to be solved.

GIANT MANGROVE FOREST, UPPER SHARK RIVER

As the boat approached land we saw that the mangrove

forest which borders so much of the Gulf was exceptionally tall. The

vegetation is not usually more than 20 or 30 feet high; but along the

southwest coast from the vicinity of the Broad River south to the Cape

Sable beaches is an area known as the giant mangrove forest. Like a

solid wall growing directly out of the water, the trees (buttonwood,

black mangrove and red mangrove) reach a height of approximately 75

feet. In a land of generally scrubby vegetation and open prairies it is

something to marvel at. Botanists have asserted that it is the tallest

forest of its type in the world .

Our pilot steered toward the mouth of Harney River

that appeared as two openings. The chart showed a small island or key in

the middle of the mouth with a number of shoal areas on which a boat

might run aground or have her bottom scraped by coon oyster beds. With

little possibility of another vessel's coming along in less than a week,

if then, the idea of getting stuck in a place where one could not travel

except by boat is a rather serious consideration. Fortunately, after

careful sounding with the lead and frantic signalling to the pilot from

one of us who sat astride the bow, we emerged into the calm, deep waters

of the Harney.

|

PROPOSED PARK TWICE

AS LARGE AS RHODE ISLAND

The proposed Everglades National Park, authorized by

Congress on May 30, 1934, includes an area of 2,272 square miles, nearly

double the domain of the state of Rhode Island. The park will border the

Gulf of Mexico from the Tamiami Trail on the north to Cape Sable, a

point 350 miles farther south than Cairo, Egypt. The tropical glades,

long noted for their great wealth of flora and fauna, and the Big Bend

of Texas and Isle Royale of Michigan, constitute the three national park

projects.

|

The giant mangrove forest came to the water's edge on

both banks. No parrots, alligators or flamingos in the background, in

fact there was not a sound of life to break the sepulchral silence of

the forest. The "land," if it can be called such, was oozy marl and the

entire area is inundated during spring tides. No dead trees so dear to

the hearts of all wildlife technicians were on the forest floor. Do not

ask me why. Perhaps these mangroves just go on living forever. To say

that the mangrove forest is beautiful is to tell a bald falsehood;

rather, let us call it impressive. I doubt if anyone has looked or will

look into that gloomy forest without saying to himself: "Wouldn't it be

terrible to have to wade in there?"

It was with a distinct feeling of relief that we

spotted two tiny black dots wheeling above the trees far off to the

east. After getting them into the range of our binoculars, we found them

to be short-tailed hawks, one of the rarest and least known species of

birds in America. To the casual observer, the short-tails might appear

similar to any of the red-shouldered hawks so common in Florida, except

perhaps a little darker; but to the ornithologist the species is well

worth coming all the way from the North to see. Southern Florida marks

the northern limit of the species' range and, for all we know,

short-tailed hawks are just as well established in the Everglades region

now as in primitive times.

The mangroves along the shorelines became smaller as

we progressed upstream and, differing from those at the coast, appeared

to have more aerial roots dropping to the water from their branches. A

flock of little blue herons took to the air as we rounded a bend of the

river, the adults slaty blue and the immature birds almost pure white.

They went squawking off in the distance flopping this way and that in

none too graceful flight. Belted kingfishers swooped across the water

uttering their familiar stuttering call just as they do along cool

streams in far away New England on summer days. Now and then a coot

rushed for cover beneath the mangrove roots.

I have often wondered how far away one can see a

flock of white ibises. It must be many miles. We were attracted by a

flash of minute, white dots like the signal of a heliograph. It is a

familiar sight in the Everglades country caused by the sun's shining

upon the backs and wings of a flock of white ibises as they circle about

in the ascending warm air during the heat of the day. Closer at hand it

is possible to see the alternate light and shadow of the birds, although

at a distance only the white flashes are visible.

We stood on the roof of the pilot's house to get a

better view. From that elevated position it was possible to see over the

tops of the mangroves fringing the shorelines to the broad flat

stretches of wet prairies beyond. The general term Everglades usually is

applied to most of southern Florida, but in its stricter sense it means

the great prairie region from Lake Okeechobee southward through the

proposed national park. In other words, the mangrove forest is not

really a part of the Everglades. Lake Okeechobee formerly overflowed the

Everglades each year and this great sheet of water, augmented by rains

in the Glades themselves, kept them wet. Since drainage canals have been

dug, the water has been diverted, the 'Glades dry out in winter, fires

start, and both wildlife and its environment suffer. We looked out over

these limitless Everglades -- vast stretches of grasses and sedges

interrupted now and then by a string of mangroves following a river such

as we were moving up, or by patches of vegetation known as hammocks. If

the water level rose one foot it would have covered the land to a depth

of at least eight inches as far as we could see. No wonder two "conchs"

(natives) of the Florida Keys made us stop our auto once on the highest

bridge of the Overseas Parkway so that they could get out and look

around. It was the highest point one of them had ever been on. The other

had visited the lookout atop the Dade County Office building in Miami.

The bridge, incidentally, is about as high above the water as an

ordinary fire tower is from the ground.

Tarpon Bay was reached early in the afternoon. It is

little more than a widening of the river, although both the Shark and

the Harney drain from it. Geologists have ventured the opinion that

during a late Pleistocene subsidence the entire west coast of the

proposed park dropped a bit, leaving the Ten Thousand Islands and a

string of inland waterways of which Tarpon Bay is but one. I have never

met anyone who has negotiated the waterways from Tarpon Bay

northwestward, paralleling the coast through Rogers River Bay, Big

Lostmans Bay, Alligator Bay, and so on. One man tried it and I

understand the Coast Guard found him by airplane.

During the late nineteenth century, great bird

rookeries in these inland lakes were almost wiped out by plume or

aigrette hunters. It was fashionable at that time for ladies to wear on

their hats the nuptial plumes of egrets and this caused a slaughter of

the birds during the breeding season. We anchored off a little island

upon which grew a single cabbage palm. Incongruously, there was a big

white sign board admonishing all to protect the birds and bearing the

name: "The National Association of Audubon Societies, 1775 Broadway, New

York City." It reminded us of other words engraved on a bronze plaque

placed on the very tip of Cape Sable which is the southernmost point on

the United States mainland. It reads: "Guy M. Bradley, 1870-1905,

Faithful unto Death as Game Warden of Monroe County he gave his Life for

the Cause to which he was Pledged." It also is signed by the Audubon

Society which was seeking at that time to stop the terrible destruction

of egrets, spoonbills and other birds that were being killed for their

plumes.

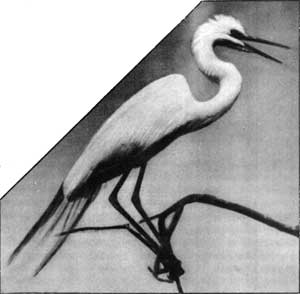

AMERICAN EGRET

|

Toward evening the American egrets that had been

feeding back in the 'Glades started toward their roosts in the mangroves

bordering Tarpon Bay. The "long whites," as the natives call them, are

the familiar "white cranes" found in the North during the summer. Once

they were very rare; now they are protected and seen more often. They

came winging in from the east singly or in small flocks, their long

black legs sticking out straight behind them. As more and more of the

birds settled in the mangroves, each just out of pecking distance of its

neighbor, they looked for all the world like white ornaments on a long

line of Christmas trees. At least 2,000 of the birds were within sight

and others could be seen coming to trees around a bend of the bay.

The sun had just set when a whistle of wings overhead

drew our attention to a flock of white ibises as they veered away from

the boat. They were flying in characteristic formation with a cluster of

birds in the front and a long string behind like the tail of a comet.

The birds making up the "tail" acted as though they were tied together.

When one dipped, all the rest dipped. About 100 birds made up the

forward group and around 300 the tail. In the distance other flocks

could be seen heading for a mutual rendezvous near the coast. A single

wood ibis landed with an ungainly flop on a dead tree near our boat.

Seeing us, it flew quickly away, calling out in a guttural voice while

its heavy wings bump-bump-bumped much like the beat of a small tom

tom.

One of the charms of the wilderness is the sensation

it gives one of being transported into the past to a bit of America as

it was before the white man came. In the Everglades, it is somewhat

different. One feels much like Mark Twain's Connecticut Yankee must have

felt when he found himself suddenly in the midst of King Arthur's court.

The land that seems to have just half emerged from the sea to form a

continent, the birds off somewhere in the distance squawking like their

antediluvian ancestors, a ripple in the water that might be an alligator

or might be a manatee, the incessant sound of batrachians, the strange

silhouettes of multiple-rooted mangroves, the harsh rattle of palm

fronds, all combine to give one the peculiar feeling that he is somehow

back in the geologic ages -- not before the white man came, but before

there was any such thing as man. At such times it is a good idea to go

below, close the screen over the hatch, and start a game of poker.

Early in the morning we took the skiff with an

outboard motor and started toward the headwaters of the Shark River.

Winding back and forth through the innumerable waterways, it was with

some surprise that we came upon a house boat tied to the bank. Some

banana trees grew nearby, indicating an old Seminole camp that probably

had been situated on a shell mound. A long line or raccoon skins were

drying on stretchers near the bananas. The occupant of the boat, who

looked like the picture of Blackbeard the pirate, came to the door and

waved to us as nonchalantly as if we were in the fiftieth boat that had

passed that morning. He was barefooted, of course, and wore his

dungarees rolled up to his knees. A hairy chest, a bearded chin, and a

quid of tobacco tucked in one cheek, made up the principal features of

our "buccaneer." Some white feathers floating about in the water bore

evidence of what he had eaten for supper the night before.

Birds were abundant. There seemed to be a continual

flap of wings as Louisiana herons, little blue herons, Ward's herons,

blue-winged teal, Florida ducks, American egrets, white ibises, wood

ibises, snowy egrets, black-crowned night herons, green herons, coots

and other birds took to the air. A school of mullet went through a shoal

area, jumping out of the water in their haste. Sometimes they jump right

into one's boat (I have witnesses). We searched in vain for an

Everglades kite, a bird whose sole food is a species of large snail. If

it still is to be found within the borders of the proposed park, it must

be at the headwaters of some of those rivers along the west coast, for

when the 'Glades were drained and the snails became scarce, the kite

disappeared also. Shooting probably helped to extirpate the species from

most of lower Florida.

Vegetation along the banks of the little stream that

we were following had changed to giant ferns, buttonwood and coco plum;

occasionally live oaks, cabbage palms and custard apples broke the

monotony. Grasses and sedges about shoulder high gradually replaced the

larger growth. The water became shallower and weeds were constantly

clogging the propeller, so we started back. One of the party threw out a

line with a spinner attached and promptly brought aboard a nice

large-mouth bass. "Fishermen's Paradise" is an overworked term. From the

number of such places it would appear that the average fisherman need

never fear descent to the nether regions. Hence, even though severely

tempted, we shall not use the term here. Bass and snook appeared to be

ready to grab our spinners before they were thrown overboard. Possibly

nobody had ever fished there before, but from all evidences the supply

should hold well with fairly heavy fishing. They were not little fish

either.

Taking a different route back, we passed the location

of the former Shark River rookery. Not a single bird has nested there

since about 1935. Ornithologists had estimated previously that there

were hundreds of thousand of birds -- some even said a million -- with

most of them white ibises. Now they have gone and nobody knows why. It

is claimed that the drying of the Everglades through drainage, with a

consequent reduction in the numbers of fresh water crayfish and other

organisms, caused the birds to move out. One cannot help speculating on

how many tons of food must have been required to keep so many birds

alive day by day. White ibises are known to move their rookeries

occasionally after the trees die from the effects of so many birds. At

any rate, the birds are gone and, for a time at least, nobody can have

the superlative thrill of seeing nearly a million of them nesting in one

mammoth rookery in the southern Everglades region.

The usual number of small alligators was noted as

well as two big ones - both in a hurry to get out of our way. A few

"gator crawls" were seen along the banks where the big saurians

habitually move from one waterway to another. Our friend the pirate may

have had something to do with the dearth of the animals. Fortunately,

the alligator is a prolific species and it does not take much

imagination to visualize what will happen when the area receives

National Park Service protection. Otter sign was not uncommon. An adult

with two young, seen at a distance, at first resembled just three more

turtles.

Upon returning to the boat, we found that we had

missed seeing a manatee. Those who stayed aboard while we went exploring

said that they had watched an old sea cow feeding in Tarpon Bay. The

manatee or sea cow is the homeliest, laziest and most innocuous mammal

in the world. It is built along the general lines of a fat old seal and

lives a sedentary life at peace with its neighbors. Perhaps its only

enemy besides man is a shark, and perhaps it is not. It grazes just like

a pasture cow on the abundant manatee and turtle grass that grows in the

water. Manatees sometimes travel in herds, sometimes alone. They are

seldom seen unless washed ashore because they feed under water and push

their wrinkled snouts above the surface only now and then for a breath

of air. They are becoming very rare and unless the Everglades National

Park is established soon the species may be lost from the United States,

although the state of Florida already has enacted stringent laws against

killing manatees.

It was decided to try to make the harbor near Cape

Sable by nightfall. Accordingly, we started down the Shark River soon

after lunch. In general the stream resembled the one up which we had

come, for there was little life in the water or along the shores. A

small flock of white pelicans flew over, headed, we supposed, for the

Cape Sable area. A snake bird, or anhinga, or water turkey if you will,

performed for us. It dropped from its perch on a small mangrove and

disappeared beneath the water. Then its head and long, snake-like neck

reappeared and the bird swam out of sight. Two swallow-tailed kites

flapped across an open glade like a pair of huge black and white

butterflies. About 25 pairs now nest in the proposed park. Once the bird

was found as far north as Minnesota, but it is seldom seen today outside

of Florida, especially the Everglades region. The name of the species is

taken from its long forked tail that moves this way and that during

flight. Some consider it the most beautiful bird in North America;

despite the fact that we hold out for the white ibis, we will not say

that they are wrong. It is a sad commentary on our civilization when we

realize that swallow-tailed kites have been shot out simply because they

are easy targets and bear a remote resemblance to hawks that might eat

chickens.

The labyrinth at the mouth of the Shark River is a

maze of islands that could be charted only from aerial photographs.

Long, long ago Ponce de Leon saw them and tried, perhaps, to thread his

way through. The water is quite deep between them, but they all look

alike with giant mangroves growing over their entire surface. Our

estimation of our pilot's skill went to a new height when he

successfully navigated through to the Little Shark River. Dead trees

began to show where the 1935 hurricane had swept. Some looked as though

they had been pruned and others were dead, leaves, bark and branches

having been blown away. The farther south we progressed, the worse was

the hurricane damage until scarcely a tree was to be found alive. In

some places one could look for a quarter of a mile through the forest

and not see a living thing.

A flock of brown pelicans and some royal terns were

near a boat at the mouth of the Little Shark River. The boat,

appropriately enough, was that of a shark fisherman who was after shark

skins for leather, shark liver for oil, and shark teeth for some other

purpose. We passed the anchored boat and emerged into the milky blue

waters of the Gulf.

SAWGRASS PRAIRIES AND CABBAGE PALM HAMMOCKS IN THE EVERGLADES

|