|

African Burial Ground National Monument New York |

|

NPS photo | |

The heart-shaped West African symbol called the Sankofa translates to "learn from the past to prepare for the future." The Sankofa appears in many places at the African Burial Ground National Monument, reminding us that the 419 Africans and African descendants buried here so long ago have much to teach us. Scientific study of the human remains reveals that work was hard, life was short, and people often met a violent end. Yet these people were lovingly laid to rest by family and friends.

Long neglected, overlain by two centuries of progress, the African Burial Ground reemerged in 1991 during construction of a federal office building. Widely regarded as one of the most important archeological finds of the 20th century, the rediscovery also sparked controversy. Protesters, outraged at the destruction of sacred ground, demanded that construction be halted. Local activism became a national effort to preserve the site and honor the contributions of New York's first Africans. A traditional African burial ceremony took place in 2003, when all 419 human remains were reburied on the site.

Established in 2006, African Burial Ground National Monument is a place to contemplate the spirit of the Sankofa. Obscure individuals from the past come alive again with the lessons of sacrifice, perseverance, respect, power of community, and the continual hope for a better future.

You may bury me in the bottom of Manhattan. I will rise. My people will get me. I will rise out of the huts of history's shame.

—Maya Angelou, 2003

Africans in Early New York

Africans in Colonial America were brought from different parts of the continent—including regions that are now the countries of Sierra Leone, Ghana, Cameroon, Nigeria, Mozambique, and Madagascar, among many others. They spoke different languages and practiced diverse customs and religions. Separated from their people, they were chained, packed in ships' holds, and taken away forever.

In 1626, the first enslaved laborers were brought to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, today's Lower Manhattan. Under Dutch West India Company rule these "Company slaves" had certain rights: they could own property, file grievances, be baptized, and marry. In 1644, 11 male enslaved Africans petitioned and won partial freedom and over 100 acres of farmland that became known as "the Land of the Blacks." In return, they paid the Dutch West India Company annually with corn, wheat, peas, beans, "and one fat hog." This "freedom" was tenuous at best, and children of freed parents were still considered enslaved. When England took control in 1664 and New Amsterdam became New York, slavery codes became far more oppressive. By the 1720s, enslaved or free, no blacks owned land.

About one quarter of colonial New York's labor force was enslaved. Often using skills they brought from their homelands, they worked side-by-side with free people and European indentured servants. Men cleared farmland, filled swampland, and built city improvements like Broadway and The Wall. Enslaved African women toiled in their owners' homes, carrying large water vessels, cooking from raw ingredients over a fire, boiling water for laundry, and caring for their owner's families in addition to their own. Children started work young. Common causes of death were malnutrition, physical strain, punishment, and diseases like yellow fever and smallpox. Despite extraordinary assaults on their humanity, these Africans and their descendants found dignity and community through familiar cultural rituals, including burial of the dead.

Sacred Ground

From 1626 through the late 1700s, Africans and African descendants gathered when they could to bury their loved ones. The original "Negros Buriel Ground," as it was labeled on a 1755 map, covered 6.6 acres, including today's African Burial Ground National Monument. For most of the Colonial era and even beyond, it was the only cemetery for some 15,000 Africans and African descendants.

No accounts survive from the people who buried their friends and loved ones here, but we know quite a bit about the cemetery's history. A 1697 Dutch law banned African burials in New York City's public cemetery, so the African burial ground lay north of the city limits near a ravine. In 1745 the city expanded northward, and a new defensive wall—the "palisade"—bisected the sacred burial ground.

Colonial laws made African funerals essentially illegal. Enslaved Africans were prohibited from gathering in groups of 12 or more or holding burials after sunset. But the dead were nonetheless buried with dignity and respect according to African traditions. They were buried individually in coffins with heads toward the west, so as to face east when they arose in the afterlife. Burial shrouds were secured with straight pins. Coins covered closed eyes. Other objects that accompanied some burials included reflective objects, buttons, jewelry, and shells. One young child was found with a silver pendant around the neck. A woman with front teeth filed in an hourglass shape had beads placed around her waist. A man's coffin lid had a heart-shaped pattern—perhaps a Sankofa—created with brass tacks and nails.

The burial ground was closed in 1794 and the land divided into lots for sale. Over the next two centuries, New York City's growth obscured the graves. The burial ground was covered with layer upon layer of buildings and fill material, which protected the human remains until rediscovery in 1991.

Rediscovery, Reinterment, Remembrance

Long forgotten by most of the world, the African Burial Ground came to light in 1991. During the early construction phase for the federal office building at 290 Broadway, workers found human burials. Over the next two years, about an acre of the original 6.6-acre cemetery was excavated, and 419 skeletal remains were removed from the ground.

Controversy immediately arose over the disturbance of the sacred ground and questions about whether the remains were being respectfully cared for. African descendants, clergy, politicians, scientists, historians, and concerned citizens united to halt the excavation. The protesters' voices, petitions, and a 24-hour vigil at the site in 1992 proved successful. Congress acted to temporarily stop the construction. The building plans were altered to provide space for memorialization.

The remans were transferred to Howard University in Washington, D.C., for study at the Cobb Laboratory, one of the nation's leading African American research institutions. Noted scholars and researchers conducted intense examination and analysis of the history, physical anthropology, and archeology of the burial ground site and the human remains. The careful study of each bone, fragment, and accompanying burial objects revealed a wealth of information about life and death for Africans in colonial New York.

In October 2003, all 419 remains were placed in mahogany coffins from Ghana that were hand-carved and lined with Kente cloth. Thus began the six-day Rites of Ancestral Return, organized by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The journey started at Howard University, where thousands attended the departure ceremony. The procession, greeted by crowds along the way, continued through Baltimore, Wilmington, Philadelphia, Newark, Jersey City, and finally ended in New York City. The coffins were reinterred very near where the remains were originally found. Seven earthen mounds now mark this site.

Meanwhile, community activists rallied to preserve part of the burial ground and commemorate African history and culture in New York City. Their efforts led to the creation of New York City's first below-ground landmark in 1993. In April 2005 the design for the outdoor memorial was selected in a public review process managed by the National Park Service in partnership with the General Services Administration (GSA). At the center is a "cosmogram," the crossroads of rebirth in Congo tradition. This contemporary architectural expression combines feminine and masculine forms and is inspired by art, music, painting, and sculpture. It is oriented toward the rising Sun along an east-west axis, the same way that the bodies were buried.

African Burial Ground National Monument was created by Presidential proclamation on February 27, 2006, and officially opened to the public on October 5, 2007. Today, the African Burial Ground is a place of remembrance. The people and their stories teach us how free and enslaved Africans contributed to the physical, cultural, and spiritual world of Lower Manhattan in colonial times—and to our nation's beginning.

Your Visit to African Burial Ground

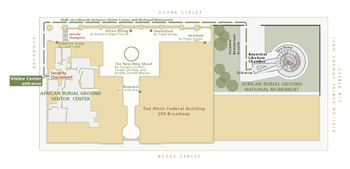

(click for larger map) |

Getting to the Monument

The African Burial Ground National Monument is in Lower Manhattan just

north of City Hall at Broadway and Duane Street. It is easily reached by

public transportation: take the 4, 5, 6, R, W, J, M, or Z subway line to

Brooklyn Bridge/City Hall; take the A, C, or E line to Chambers Street;

take the 2 or 3 line to Park Place. Bus lines include the M6, M15, M22,

B51.

General Information

The National Park Service Visitor Center is inside the Ted Weiss Federal

Building at 290 Broadway. There is no admission fee. For days and hours

of operation, please visit the website.

Groups should make advance reservations to ensure staff availability. Groups should arrive 30 minutes before the scheduled start of their tour. There is a resource library; schedule appointments in advance.

The African Burial Ground National Monument is available for special events. You must obtain and submit a permit; contact the site for information.

Things to See and Do

The visitor center has exhibits about the burial ground and the lives of

Africans and African descendants in New Amsterdam and New York. There is

also a theater and a bookstore. Park rangers present educational

programs.

The lobby of the Ted Weiss Federal Building displays commissioned artwork inspired by the burial ground and the early African experience in New York. Works include "Renewal" by Tomie Arai, "Unearthed" by Frank Bender, "Untitled" by Roger Brown, "Africa Rising" by Barbara Chase-Riboud, "America Song" by Clyde Lynds, and "The New Ring Shout" by Houston Conwill, Joseph De Pace, and Estella Conwill Majozo.

Outdoor Memorial

The memorial is behind the Ted Weiss Federal Building at the corner of

Duane Street and African Burial Ground Way (Elk Street). There are no

restrooms outside near the memorial.

The Circle of the Diaspora includes signs and symbols engraved in the perimeter wall. The symbols originated in areas and cultures throughout the Diaspora, reminding us of the complexity and diversity of African cultures. The term Diaspora describes the forced and deliberate transporting of Africans during the slave trade from their homeland, and dispersing them throughout the New World.

The 24-foot Ancestral Libation Chamber represents the soaring African spirit and the distance below the ground's surface where the ancestral remains were rediscovered. The Sankofa symbol is engraved on the exterior. Reminiscent of a ship's hold, the interior is a spiritual place for individual contemplation, reflection, and meditation.

The Ancestral Reinterment Ground is the final resting place for the 419 human remains unearthed in the early 1990s. They are reburied as closely as possible to their original positions. The coffins were placed in seven crypts, and seven burial mounds mark the locations. Seven trees serve as guardians for the entrance to the Ancestral Chamber.

There is a 90-minute walking tour of Lower Manhattan entitled "A Broader View: Exploring the African Presence in Early New York." The tour begins on the front steps of Federal Hall National Memorial at 26 Wall Street and ends at African Burial Ground National Monument.

Security and Safety

All visitors and their belongings are subject to strict security

screening before entering the visitor center or the Ted Weiss Federal

Building.

• All weapons and dual-use, dangerous items are strictly prohibited.

• If you have special needs or questions, contact the site before you

visit.

The burial site is a sacred place. Please act respectfully and do not eat, drink, smoke, play loud music, or stand on the burial mounds. No loitering or soliciting in the memorial area. If you wish you may place flowers on the burial mounds.

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

|

Establishment African Burial Ground National Monument — February 27, 2006 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Archaeology Final Report: New York African Burial Ground — Volume 1 (Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., February 2006)

Archaeology Final Report: New York African Burial Ground — Volume 2: Descriptions of Burials 1 through 200 (Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., February 2006)

Archaeology Final Report: New York African Burial Ground — Volume 3: Descriptions of Burials 201 through 435 (Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., February 2006)

Archaeology Final Report: New York African Burial Ground — Volume 4: Appendices (Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., February 2006)

Draft Management Recommendations for the African Burial Ground (2008)

Finding Aid — African Burial Ground Project Records, 1935-2009, Part I: Descriptions and Indexes (c2010)

Finding Aid — African Burial Ground Project Records, 1935-2009, Part II: Collection Listing (c2010)

Foundation Document, African Burial Ground National Monument, New York (August 2018)

Foundation Document Overview, African Burial Ground National Monument, New York (September 2018)

History Final Report: The New York African Burial Ground (Ena Greene Medford, ed., November 2004)

Junior Ranger Book, African Burial Ground National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Book (Answers), African Burial Ground National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Manhattan Historic Sites Archive

Presidential Proclamation 7984 — Establishment of the African Burial Ground National Monument (George W. Bush, February 27, 2006)

Skeletal Biology Final Report: The New York African Burial Ground — Volume I (Michael L. Blakey and Lesley M. Rankin-Hill, December 2004)

Skeletal Biology Final Report: The New York African Burial Ground — Volume II (Michael L. Blakey and Lesley M. Rankin-Hill, December 2004)

The Archaeology of 290 Broadway

Volume I: The Secular Use of Lower Manhattan's African Burial Ground (Charles D. Cheek and Daniel G. Roberts, eds., comp., 2009)

Volume II: Archaeological and Historical Data Analyses (Charles D. Cheek and Daniel G. Roberts, eds., comp., 2009)

Volume III: Artifact Catalog (John Milner Associates, Inc., 2009)

Volume IV: Conservation of Materials From the African Burial Ground and the Non-Mortuary Contexts (Cheryl J. LaRoche, 2009)

The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York

Volume 1: The Skeletal Biology of the New York African Burial Ground - Part 1 (Michael L. Blakey and Lesley M. Rankin-Hill, eds., 2009)

Volume 1: The Skeletal Biology of the New York African Burial Ground - Part 2: Burial Descriptions and Appendices (Michael L. Blakey and Lesley M. Rankin-Hill, eds., 2009)

Volume 2: The Archaeology of the New York African Burial Ground - Part 1 (Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., 2009)

Volume 2: The Archaeology of the New York African Burial Ground - Part 2: Descriptions of Burials (Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., 2009)

Volume 2: The Archaeology of the New York African Burial Ground - Part 3: Appendices (Warren R. Perry, Jean Howson and Barbara A. Bianco, eds., 2009)

Volume 3: Historical Perspectives of the African Burial Ground: New York Blacks and the Diaspora (Edna Greene Medford, ed., 2009)

Volume 4: The Skeletal Biology, Archaeology, and History of the New York African Burial Ground: A Synthesis of Volumes 1, 2, and 3 (Statistical Research, Inc., 2009)

Volume 5: The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York (2009)

afbg/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025