|

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Nebraska |

|

NPS photo | |

About 19-20 million years ago drought struck the western Nebraska plains. Deprived of food, hundreds of animals died around a few shallow water holes. Over time their skeletons were buried in the silt, fine sand, and volcanic ash carried by the wind and reworked by streams. An ancient waterhole with hundreds of fossilized skeletons is preserved today in the Niobrara River valley at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument.

The early 1900s discovery of this deposit and others nearby was important to the developing science of paleontology. Study of these fossils—continuing today—has helped answer questions about the past. But what were the conditions that created this drought and brought these animals together so long ago? Millions of years before the drought, in the Age of Dinosaurs, erosion from mountain ranges to the west formed the bed of a shallow sea. About the time dinosaurs went extinct, the Rocky Mountain ranges were forming, the sea receded, and tropical lowlands occupied what is now the Great Plains.

North America's climate became ever cooler and drier, and volcanic activity in the western United States produced enormous amounts of ash blown eastward. Ash-mantled plains were home to great herds of plant-eating mammals and their predators. As in today's east African savannas, the rich volcanic soils supported grasses that, together with small trees and bushes along shallow streams, fed grass- and leaf-eaters. Many animals that thrived here depended on the moderate climate for their survival, and their numbers expanded to the capacity of the food available.

In time the climate grew more arid. The Rocky Mountains kept rising and blocked the flow of moisture-laden air from the west. With less rain came plants that could survive with less water. Droughts were common. Streams dried up and grasses withered.

Water-dependent animals congregated at water holes between times of feeding on the dwindling plants. Large animals like the rhinoceros and the chalicothere Moropus, a distant relative of the horse, finally could not travel far enough to find fresh forage, so they died in the shallow water of the few remaining ponds.

Hundreds and thousands of some species died, littering the area in and around water holes with their remains. In time the rains returned, the streams filled, and the process of burial began. Silt, sand, and ash covered the remains, burying them under several feet of wind- and stream-transported sediment.

Fossils at Agate Fossil Beds

What Animals Roamed Here? While some animals whose fossil remains were found at Agate Fossil Beds are now extinct, others are represented by a few modern relatives or descendants.

Palaeocastor had powerful clawed forelimbs for digging and long, curved teeth like modern beavers. Herds of Stenomylus, gazelle-camels about two feet tall, grazed grasslands beside the three-toed, pony-sized rhinoceroses Menoceras. The most common mammal in the bonebed, Menoceras may have roamed these plains in large herds. Only a few oreodonts, about the size of a sheep, have been found here, and they are most common in the carnivore dens nearby, where they were the prey of beardogs.

Fossil remains of the ancestors of the modern horse, Parahippus, also have been found in the waterhole but are rare. Horses became extinct in North America millions of years after the die-off event at Agate, not to return until brought back by the Spaniards. Moropus was quite fantastic. Related to both the horse and rhinoceros, it was large, had back legs shorter than the front, with great clawlike hooves. It probably browsed leaves of bushes and small trees.

Another large animal, Dinohyus, was a giant entelodont related more closely to cows and pigs than to carnivores. Tracks of this huge scavenger have been found in the waterhole mud. It broke bones with its teeth (bite marks show on chalicothere limb bones). Discoveries in the 1980s included fossil remains of beardogs and other carnivores and their dens—one of the few paleontological sites of this type in the world.

Discovery of the Fossils Most of the land that is now Agate Fossil Beds National Monument was once part of the Agate Springs Ranch owned by James and Kate Cook. They bought the ranch from her parents in 1887, a few years after they had found "a beautifully petrified piece of the shaft of some creatures leg bone."

Erwin H. Barbour of the University of Nebraska, in 1892, was the first scientist to examine the strange Devil's Corkscrews at Agate, later recognized as the fossilized burrows of Palaeocastor.

In August 1904, O.A. Peterson of the Carnegie Museum discovered the great bonebed with the help of Harold J. Cook, son of James and Kate. Scientists from Yale University, the American Museum of Natural History, and other institutions also worked here, mostly between 1904 and 1923. The competition to find the best bones sometimes grew spirited. The work of these bone hunters formed many outstanding collections in museums around the world.

The Age of Mammals

Life in the Cenozoic Era—the Last 65 Million Years

From simple beginnings great numbers and varieties of life forms have evolved and populated the Earth. For 140 million years before the Cenozoic Era, dinosaurs held dominion over the land. Mammals also existed, but they were small and not abundant. As the dinosaurs perished the mammals took center stage. Even as mammals increased in numbers and diversity, so did birds, reptiles, fish, insects, trees, grasses, and other life forms. The fossil record gives us a fascinating glimpse into the Cenozoic Era. Without fossils we would have little way of knowing that ancient animals and plants were different from today's. With fossils we discover that an extraordinary procession of organisms lived in North America and around the world. Species changed as the epochs of the Cenozoic Era passed. Those that could tolerate the changes in the environment survived. Other species migrated or became extinct. The fossil record tells these stories, but the study of fossil remains, paleontology, also raises many questions: What types of environments did these plants and animals live in? How did they adapt to climatic changes? How did different groups of plants and animals interrelate? How have they changed through time?

Fossils are studied in the context in which they were found and as one element in a community of organisms. Every fossil can serve as a key to unlock knowledge, so the National Park Service is especially concerned with the protection of these keys as the questions unfold. The Cenozoic Era continues today and scientists estimate that as many as 30 million species of animals and plants now inhabit the Earth. This is a mere fraction of all life forms that have ever existed. Scientists now think that about 100 species will become extinct every day, a rate accelerated by human actions. Pollution of the air and water; destruction of forests, grasslands, and other ecosystems; and other adverse changes to Earth's environment challenge life's very ability to survive. "Looking back on the long panorama of Cenozoic life," Finnish scientist Bjorn Kurten has said, "I think we ought to sense the richness and beauty of life that is possible on this Earth of ours." It is no longer enough to plan for the next generation or two, Kurten suggests. We should plan "for the geological time that is ahead.... It may stretch as far into the future as time behind us extends into the past."

(Park names following captions indicate where fossils were found.)

Paleocene

Began 65 million years ago

The Paleocene Epoch began after dinosaurs became extinct. Mammals that had lived in their shadows for millions of years eventually evolved into a vast number of different forms to fill these newly vacated environmental niches. Many forms of these early mammals would soon become extinct. Others would survive to evolve into other forms.

The variety of other animals and plants also increased, and species became more specialized. Although dinosaurs were gone, birds continued to flourish, and reptiles lived on as turtles, crocodiles, lizards, and snakes.

As the Paleocene began, most mammals were tiny, like this rodent-like multituberculate. With time mammals grew in size, number, and diversity.

Palm trees and crocodilians thrived in the subtropical forests of the Paleocene and much of the Eocene.

Fossil Butte NM

Eocene

Began 55 million years ago

In the Eocene Epoch mammals emerged as the dominant land animals. They also took to the air and the sea. The increasing diversity of mammals begun in the Paleocene continued at a rapid pace in the Eocene. The many variations included some of the earliest giant mammals. Some were successful, some not. The fossil record reveals many mammals quite unlike anything seen today. Increasingly, however, there were forest plants, freshwater fish, and insects much like those seen today.

Bats, the only type of mammal ever to develop the power of active flight, took to the air more than 52 million years ago.

Fossil Butte NMMany freshwater fish lived in North American lakes during the Eocene Epoch. Gars, herring, and sunfish are similar in appearance to those Eocene fish.

Fossil Butte NMGroves of giant redwood trees once grew throughout western North America. Changes in climate were responsible for these trees' shrinking range.

Florissant Fossil Beds NMDelicate bones of shorebirds, including frigate birds, are preserved in the fine-grained sediment of Eocene lake deposits.

Fossil Butte NMButterflies and many other insect groups co-evolved throughout the Cenozoic with the increasing variety of flowering plants. These insects became important agents of pollination.

Florissant Fossil Beds NMThe variety of flowering plants exploded just before, during, and after the Eocene. They would populate the land with all sorts of new species of trees, shrubs, and smaller plants. Cattails grew in the shallows of Eocene freshwater lake edges.

Fossil Butte NMAncient tapirs such as Heptodon browsed near the shores of Fossil Lake in what is now western Wyoming. Unlike modern tapirs, Heptodon had a very small snout.

Fossil Butte NMTsetse flies occur today in tropical Africa and as fossils in the Florissant formation.

Florissant Fossil Beds NMLiving in Eocene forests, the first horse-like animals were barely bigger than today's domestic cat. Throughout the Cenozoic Era their size increased. Their legs became longer, and their feet changed from many-toed to single-hoofed for faster running. Their teeth evolved from being adapted for browsing to being adapted for grazing. Fossil horses occur at many sites in the National Park System.

Coryphodon had short, stocky limbs and five-toed, hoofed feet, closely resembling the tapir. Its brain was very small. The males had large tusks. Coryphodon also lived on land not far from the shores of Fossil Lake.

Fossil Butte NM

Oligocene

Began 34 million years ago

The Oligocene Epoch was a time of transition between the earlier and later Cenozoic Era. The once warm and moist climate became cooler and drier. Subtropical forests gave way to more temperate forests.

Late in the Oligocene, savannas—grasslands broken by scattered woodlands—appeared. These changes caused mammals, insects, and other animals to keep trending toward specialization. Some adapted to the diminishing forests by becoming grazers. Early types of mammals continued to die out as more modern groups—dogs, cats, horses, pigs, camels, and rodents—rose to new prominence.

Ekgmowechashala marked the end of the original primate lineage in North America. A small lemur-like primate, it may have used large skin folds to glide from tree to tree. Its name means "little cat man" in Lakota, which the discoverer understood to be their name for monkey.

John Day Fossil Beds NMOreodonts, a group of sheep-like animals, were successful in the Eocene and Oligocene. By the end of the Miocene they had completely died out.

Badlands NP

Miocene

Began 23 million years ago

The abundance of mammals peaked in the Miocene Epoch. The refinement in life forms that marked this epoch saw many animals and plants develop features recognizable in some species today. The forests and savannas persisted in some parts of North America. Treeless plains expanded where cool, dry conditions prevailed. Many mammals adapted for prairie life by becoming grazers, runners, or burrowers. Large and small carnivores evolved to prey on these plains-dwellers. Great intercontinental migrations took place throughout the Miocene, with various animals entering or leaving North America.

Moropus was a distant relative of the horse and one of the more puzzling mammals. For many years paleontologists thought its feet had claws rather than hooves.

Agate Fossil Beds NMLacking other defenses, some larger rodents, such as the dry-land beaver Palaeocastor, lived in colonies beneath the High Plains of North America. Their burrows remain as trace fossils today.

Agate Fossil Beds NMRhinos were varied and abundant during most of the Cenozoic Era. Around the world they ranged in size from the three-foot-tall North American species Menoceras to a giant Asian species, the largest land mammal yet found in the fossil record.

Agate Fossil Beds NMDaphoenodon was carnivorous. It differed from the earliest true dogs of the Oligocene Epoch. Its so-called "beardog" family eventually went extinct.

Agate Fossil Beds NMDaeodon (formerly called Dinohyus, "terrible hog" had bone-crushing teeth enabling it to scavenge the remains of other grassland animals.

Agate Fossil Beds NMThe tiny gazelle-camel Stenomylus probably grazed in herds for protection from predators.

Agate Fossil Beds NM

Pliocene

Began 5 million years ago

Most life forms of the Pliocene Epoch would have been recognizable to us today. Many individual species were different, but distinguishing characteristics of various animal and plant groups were present. Evidence of wet meadows and of dry, open grassland environments has been found in the Pliocene. Toward the end of this epoch grasslands spread across much of North America, brought on by an ever cooler, ever drier climate. Horses and other hoofed mammals and the powerful, intelligent predators that preyed on them continued to prosper.

Mammut was a type of mastodon that migrated to North America in the Pliocene. In the early Pleistocene another elephant group called mammoths joined the mastodons. By the late Pleistocene mastodons and mammoths both became extinct, possibly because of climatic changes or hunting by early people.

Hagerman Fossil Beds NMWillow, alder, birch, and elm grew on the ancient river plains of the Pliocene. These same plants grow along streams and rivers today.

Hagerman Fossil Beds NMHorses such as this early zebra-like version of the modern horse were superbly adapted to life on the grassy plains.

Hagerman Fossil Beds NM

Pleistocene

Began 2 million years ago

The Pleistocene Epoch began with widespread migrations of mammals and ended with massive extinctions. It was also a time when glaciers repeatedly covered much of North America.

Known evidence of humans living in North America dates to about 12,000 years ago. In this relatively brief period we have had a profound effect on the plants and other animals here. Do we have a responsibility to try to limit our effects on other species, or are humans simply a natural agent of extinction?

Endangered species today include the loon, timber wolf, and Kemp's ridley sea turtle. The National Park Service is among the many public agencies and private organizations entrusted with helping to protect endangered plants and animals and to preserve the diversity of life throughout North America.

The Cook Collection of American Indian Artifacts

James H. Cook was a frontiersman, hunter, and scout before he settled on the Niobrara River. Cook first met Chief Red Cloud in 1874 when Yale University Professor Othniel C. Marsh came to western Nebraska looking for fossils. The Oglala Lakota (Sioux) were suspicious of Marsh, because most white men they knew were gold seekers. But "Captain" Cook helped convince Red Cloud and the other Oglala that Marsh was what he said he was, a bone hunter.

Over the years Cook often helped the Oglala and Cheyenne. A steadfast friendship grew up between the Cook family and the Indians, who brought gifts and told them stories about individual items. The family's collection now belongs to the park, and many items are displayed in the visitor center.

Pictographs painted 1 on hides—one of a buffalo hunt and one of Custer's Last Stand—saddles, bows, shirts (including one of Red Cloud's that he gave to the Cooks), moccasins, bags, war clubs, pipes, and guns make this collection an outstanding representation of Plains Indian culture. Cook's interest in fossils led his son Harold to become a paleontologist, publishing many papers and taking part in important scientific research.

Preserved and available to researchers here at the park are the Cook collection, other natural history specimens, the paleontological library of Harold Cook, and family correspondence, books, and papers that span four generations.

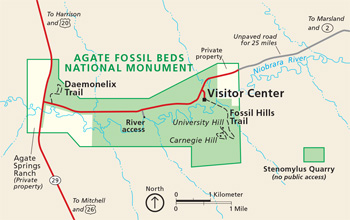

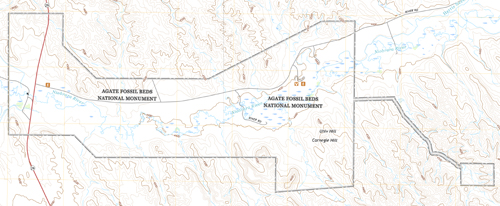

(click for larger maps) |

Exploring Agate Fossil Beds

Visitor Center and Museum Stop here for information, activity schedules, exhibits on fossils and artifacts, and a short movie. Open daily except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. A picnic area is nearby. Call ahead for educational programs.

Interpretive Trails Two trails lead to important fossil discovery areas. The 2.7-mile Fossil Hills Trail leads to University and Carnegie hills, where most of the digging took place in the early 1900s. The one-mile Daemonelix—Devil's Corkscrew—Trail is near the River Road-NE 29 junction. It leads to the fossilized corkscrew burrows of the small beaver Palaeocastor.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information, ask at the visitor center, call, or visit our website.

Stay Safe, Protect the Park Use common sense to prevent accidents. • Rattlesnakes live here, but you are unlikely to encounter one. Please stay on the trails and out of high grass. • Federal law protects all natural and cultural features in the park. Do not remove any fossils, animals, rocks, plants, or artifacts. Leave things as you find them for others to enjoy, too. • There is some private land in the park. Respect owners' rights and do not trespass. • Keep pets on a leash and on the trails. They are not allowed in the visitor center. • Lightning kills; seek shelter before a thunderstorm hits. • No overnight camping or parking is permitted. • Open fires are prohibited. • For firearms information, check the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment Agate Fossil Beds National Monument — June 5, 1965 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

2001-2003 Status Report: Grassland Bird Monitoring at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska and Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas (David G. Peitz and Gareth A. Rowell, November 7, 2003)

Agate Fossil Beds Handbook (1980)

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: A Proposal (August 1963)

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: Archeological Investigations at Site 25SX163 Midwest Archeological Center (MWAC) Occasional Studies Series No. 6 (Danny E. Olinger, 1980)

Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Fish Inventory Final Report (Mark A. Pegg and Kevin L. Pope, c2008)

Agate Fossil Beds Prehistoric Archaeological Landscapes, 1994-1995 (LuAnn Wandsnider and George H. MacDonnel, eds., 1997)

Aquatic invertebrate monitoring at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: 2010 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR-2012/654 (Lusha Tronstad, December 2012)

Aquatic invertebrate monitoring at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: 2011 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR-2012/653 (Lusha Tronstad, December 2012)

Aquatic invertebrate monitoring at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: 2012 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR-2014/874 (Lusha Tronstad, May 2014)

Aquatic invertebrate monitoring at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: 2019 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/AGFO/NRDS-2022/1349 (Lusha Tronstad, March 2022)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate Resource Brief, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (February 2012)

Bones of Agate: An Administrative History of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (HTML edition) (Ron Cockrell, 1986)

Centuries Along the Upper Niobrara, Historic Resource Study, Agate Fossil Bed National Monument (Gail Evans-Hatch, 2008)

Faunal Survey of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (Jennifer L. Graetz, Robert A. Garrott and Scott R. Craven, January 25, 1995)

Fishes of Niobrara River at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: 2011 Survey (Richard H. Stasiak, George R. Cunningham, Scott Flash, Andrea Wagner and Adena Barela, c2011)

Fossil Management Plan and Environmental Assessment, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Draft (August 1988)

Foundation Document, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska (September 2012)

Foundation Document Overview, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska (July 2014)

Geologic Map of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska (July 2018)

Geologic Resource Inventory Report, Agate Fossils National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/080 (J. Graham, March 2009)

Grassland Bird Monitoring at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska and Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, Kansas: 2001-2003 Status Report (David G. Peitz and Gareth A. Rowell, November 7, 2003)

Hydrology of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2005/327 (Larry Martin, February 2005)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, 2007 (Daniel J. Stynes, March 2009)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (November 2011)

Monitoring the Birds of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: 2010 Field Season Report Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory Tech. Report # SC-AGFO-NPS-10-01 (J.M. Stenger, J.A. Rehm-Lorber, C.M. White and D.C. Pavlacky Jr., March 2011)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Harold J. Cook Homestead Cabin (Richard I. Ortega, March 1, 1976)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR-2018/1676 (Reilly R. Dibner, Nicole Korfanta and Gary Beauvais, July 2018)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR-2020/2-74 (Reilly R. Dibner, Nicole Korfanta and Gary Beauvais, February 2020)

Paleontological Resources Management Plan (Public Version), Agate Fossil Beds National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/AGFO/NRR-2020/2172 (Scott Kottkamp, Vincent L. Santucci, Justin S. Tweet, Jessica De Smet and Ellen Starck, September 2020)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring Protocol for the Northern Great Plains I&M Network Version 1.01 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR-2012/489 (Amy J. Symstad, Robert A. Gitzen, Cody L. Wienk, Michael R. Bynum, Daniel J. Swanson, Andy D. Thorstenson and Kara J. Paintner-Green, February 2012)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring Annual Reports: 2011 • 2012 • 2013 • 2014 • 2011-2015 • 2016 • 2017 • 2018 • 2019

Plant Community Resource Brief, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (February 2012)

Proposed Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Nebraska (HTML edition) (September 1964)

Restoration of Bison (Bison bison) to Agate Fossil Beds National Monument: A Feasibility Study NPS Natural Resource Report NRR/AGFO/NRR-2014/883 (Daniel S. Licht, November 2014)

Soil Survey of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska (2013)

Status Report of Vegetation Community Monitoring at Scotts Bluff National Monument and Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (Alicia Sasseen and Mike DeBacker, May 2005)

The 1996 Archeological Survey of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report Series No. 80 (Robert K. Nickel, 2002)

The Agate Hills: History of Paleontological Excavations, 1904-1925 (Robert M. Hunt, Jr., 1984)

The History of Agate Springs (R. Jay Roberts, Nebraska History, Vol. 47, 1966)

The Lichens of Scotts Bluff National Monument and Agate Fossil Beds National Monument (Clifford M. Wetmore, April 1998)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Agate Fossil Bends National Monument, Nebraska: 1999-2009 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2010/531 (Kevin M. James, July 2010)

White-Nose Syndrome Surveillance Across Northern Great Plains National Park Units: 2018 Interim Report (Ian Abernethy, August 2018)

agfo/index.htm

Last Updated: 31-Jan-2025