|

ALAGNAK

Alagnak Wild River An Illustrated Guide to the Cultural History of the Alagnak Wild River |

|

PORTRAIT OF TRADITIONAL LIFESTYLE

|

|

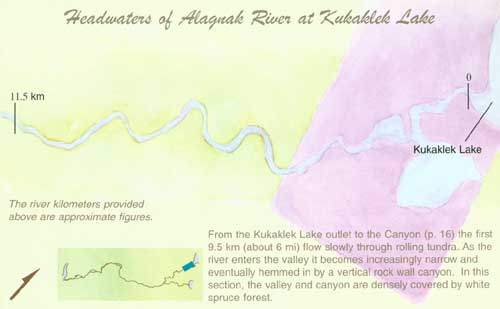

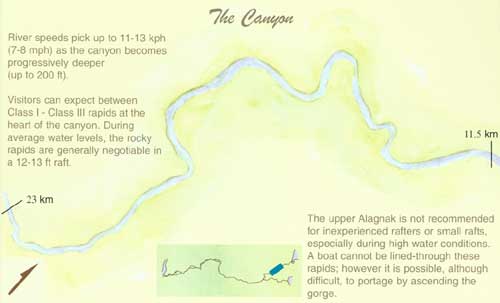

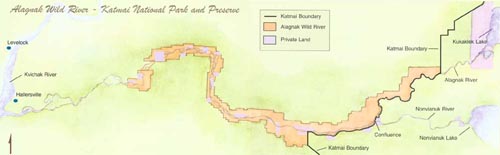

Overview: Alagnak Wild River — Katmai National Park and Preserve (click on image for a PDF version) |

A diversity of ethnic groups now comprises the communities in the Bristol Bay, Alagnak, and Illiamna regions. At contact Native residents were Alutiiq and Central Yup'ik speakers. People lived in small, closely-knit kinship-based communities and shared a similar lifestyle of subsistence hunting, fishing, and trapping. Hardships of weather, isolation, and a significant lack of modern conveniences bound communities together. Marriages, which were arranged by parents, usually depended on social status and were matriarchal in nature. Arranged marriages continued into the early part of the 20th century and served in part to enhance economic opportunities and to maintain strong familial ties with neighboring villages.

|

| Koggiung village orphans during the summer of 1919 on the lower Kvichak River. The 1918 Spanish flu epidemic was first noticed at Koggiung on May 23, 1919 and raged until June 16th, killing 39 people and leaving 16 orphans. Sisters, Kina Klein Kraun and Mary Klein Kraun are second and third from left respectively. Annie Klein Aspelund is probably fourth from left. Photo courtesy of Vickie Herrmann. |

Games were also an important aspect of life. Though fun and entertaining, games were considered excellent preparation of youngsters for life on the river. "Congregations of children and adults usually resulted in some kind of competition." Kayak races were particularly popular.

Dancing, singing, and story-telling further connected people to their communities and to their ancestors. Folktales tell of many strange beings that still inhabit the area, though rarely spoken about today. One traditional story often retold was that of the Little People. These magical creatures were believed to change forms, move mountains, and dwell in tall grassy meadows. However friendly, they were thought to capture humans and keep them for what appeared to be a short period of time while in reality many decades of the person's life may have passed. Another popular legend was that of a giant pike that inhabited the waters of Nonvianuk Lake chasing residents crossing the lake in their moose hide canoes.

|

| Spring beaver trapping along the Alagnak River in 1938-1939. From left to right: Vivian O'Neill, an unidentified woman, Eau Andrew, John Knutsen, and two unidentified boys. The Knutsen and Andrew families lived on the Alagnak River and summered on the Kvichak River. Photo courtesy of Alex Tallekpalek. |

In late May or early June, residents hunted beluga whales in Bristol Bay. Bird eggs, sourdock, wild celery, and fiddlehead ferns were gathered for personal consumption. In summer, fish were caught for smoking, drying and freezing for the winter. In the past, fish were even stored in underground pits for the preparation of fermented fish heads, a local delicacy. This practice has largely been discontinued due to the risk of botulism. As colder weather approached, residents collected salmon berries, black berries (also known as crowberries) and blueberries for winter use. Moose, caribou, and bear were hunted after the animals had grown fat from a brief season of plentiful food. In winter, smelt, trout, and grayling were harvested by ice fishing.

|

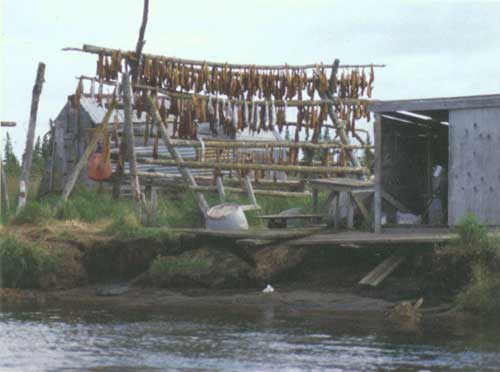

| Salmon are traditionally dried on fish racks constructed with white spruce poles and an assortment of driftwood. |

Subsistence trapping was also an important activity. Mink, otter, martin, beaver, fox, wolf, lynx, wolverine, rabbit, weasel, and squirrel were trapped for their furs. Furs may have been sold outright or used for clothing. Today some trapping still occurs to supplement income by selling furs to lodges and tourists.

The abundance of large game species such as moose has increased over the last century, perhaps due to changes in vegetation. Historic subsistence hunting of moose was much more difficult as this species was once less common. In the event that a moose was harvested, the hunter would construct a kayak on site using the fresh hide (as well as some wolverine) to transport the meat. Assembling a kayak in this manner usually took two to three days to complete. Although kayak building was an exhaustive undertaking, in this case the benefits were twofold: the hunter was assured of food and transportation. Kayaking was the primary means of transportation during open water. Dogsleds were used in the winter once the river was frozen.

|

| This photo taken in the 1930s shows one moose hide boat in the foreground and a two-hatch kayak, as well as a plank skiff in the background. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

alag/cultural-history/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jun-2009