|

Alaska Subsistence

A National Park Service Management History |

|

Chapter 1:

ALASKA NATIVE AND RURAL LIFEWAYS PRIOR TO 1971

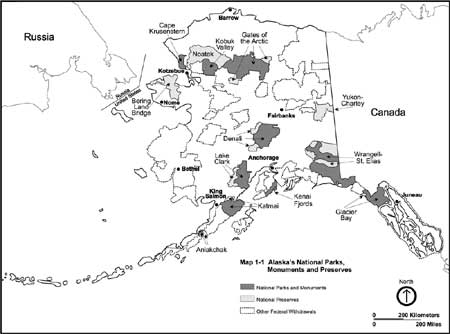

A. Alaska's Native Cultures

Before the arrival of the first European explorers, an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 people lived in the area now known as Alaska. Three separate groups of people lived there: Indians, Aleuts, and Eskimos.

Of these groups, Indians occupied more of Alaska's territory at the time of contact than any other Native group. A broad panoply of Athabaskan Indian groups, including the Dena'ina, Koyukon, Tanana, and Ahtna, occupied the vast interior valleys of the Yukon, Tanana, Copper, Koyukuk, and upper Kuskokwim rivers. Among these groups, which collectively comprised about 10,000 individuals, the Dena'ina were the only group that occupied coastal territory. In addition to these groups, a variety of coastal Indians—most notably the Tlingit, Haida, and Eyak—lived in what is now southeastern and south-central Alaska. Their territory was far smaller than that of the Athabaskans, but because of their richer resource base, the population of these three groups also numbered about 10,000.

Along the western margin of Alaska lived the Aleuts, about 15,000 of whom lived at the rime of European contact. Aleut villages were scattered along the lower Alaska Peninsula and in the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands. The various Eskimo peoples numbered about 30,000 in the mid-eighteenth century. The Eskimos, then as now, were coastal people who occupied the Arctic coastal plain, all of western Alaska, much of the Alaska Peninsula, and the Gulf of Alaska. The four main Eskimo peoples were the Inupiaq, Siberian Yup'ik, Central Yup'ik, and the Alutiiq or Sugpiaq. [1]

European exploration and settlement, which began in 1741, impacted some Native groups more than others. Hardest hit were the Aleuts, the first Native group to be exposed to the Russian fur hunters; within fifty years after the arrival of the first explorers, much of the Aleut population had been either annihilated or subjugated. To a lesser extent, many groups that lived along the coast of south central or southeastern Alaska were negatively impacted by hunting and settlement activity during the 126-year period that Alaska was known as Russian America. In addition, Natives in the middle Yukon River basin—particularly those who lived near the Hudson's Bay Company post at Fort Yukon—were influenced by the interior fur trade, and the Inupiat living in communities bordering the Chukchi Sea and Arctic Ocean were influenced by the commercial whaling trade. (Both the interior fur trade and the coastal whaling trade commenced during the 1840s.) But Native groups living elsewhere had little or no contact with Europeans, and their lifeways and population levels continued much as they had for generations. Though many Russians had little regard for Alaska's Native populations (they characterized them as "uncivilized"), [2] their narrowly focused pursuit of a single commodity—sea otter pelts—and the small number of Russian settlers were ameliorating factors in their overall influence on Native lifeways.

|

|

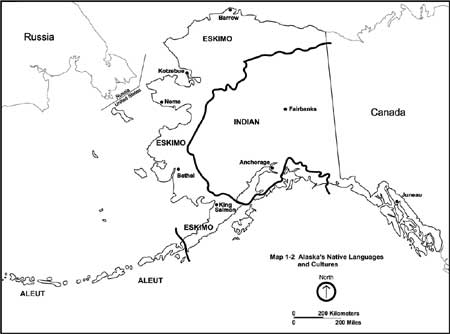

Map 1-1. Alaska's National Parks, Monuments and

Preserves.

(click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

|

B. Alaska Natives and the U.S. Government

In 1867, the United States government purchased Alaska from the Russians. (The purchase of the agreement stipulated that all Alaskans were either from "uncivilized tribes" or were "inhabitants of the ceded territory." But as David Case has noted, nearly all Alaska Natives, as a judicial practice, were categorized as "uncivilized," either because of their status during the Russian period or, as elaborated upon below, because of their treatment under existing U.S. law. [3]) At the time of the purchase, fewer than a thousand Russians or mixed-race Creoles lived in Alaska, and many of those that had been involved with the Russian-American Company or in other official capacities soon returned to Russia. In their stead came a small flood of Americans, most of whom descended on Sitka. But the lack of economic opportunities in the new possession caused many of the newcomers to return home. As late as 1880, only about 400 "whites" (as the census described them) lived in Alaska. During the following decade, major gold strikes in the Juneau-Douglas areas and fisheries developments throughout the so-called "panhandle" brought a tenfold increase in the number of non-Native residents in southeastern Alaska. Even so, the 1890 census recorded fewer than 5,000 non-Natives anywhere in the District of Alaska. Most non-Natives lived in Sitka, Juneau, Douglas, Wrangell, Kodiak, and other coastal towns and villages. [4]

Government was slow to come to Alaska; the first Organic Act providing for a civil administration was not passed until 1884, and full territorial government, via second Organic Act, had to wait until 1912. Alaska Natives, however, were ruled not from Sitka (Alaska's first capital under the U.S. flag) or Juneau (where the capital moved in 1906); instead, Native affairs were administered directly from Washington, D.C., where policies toward Indians had been a primary tenet of government policy since the days of George Washington and John Adams. An Indian policy followed during the first several decades, which promoted domestic trade and prevented foreign alliances, was eventually replaced a more hard-edged policy that sought the complete removal of Indians from the path of westering settlers. This latter policy led, in the 1840s, to the first Indian reservations. In 1849 the Department of the Interior was created, which included the Office of Indian Affairs; ever since then, working with America's Native groups has been an Interior Department function. For much of the rest of the nineteenth century, the official policy of both Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court was to protect Indians and promote their welfare. But other elements in the government—the Army and many in the Office of Indian Affairs among them—were hostile to Native hopes, and a strong majority of Americans had little sympathy for the Indians' plight. During the 1880s the publication of several stirring works, including Helen Hunt Jackson's A Century of Dishonor and her better-known Ramona, brought forth the first seeds of nationwide sympathy for the Natives' cause. By that time, most Native Americans living in the coterminous states were confined to reservations and had, to a large extent, become wards of the government. [5]

Alaska's Natives, as noted above, were largely ignored by governmental Indian policy during the first three decades of American rule, primarily because their land and resources were either "undiscovered" or were not coveted by non-Natives. But when Native and non-Native resources did come into conflict, Natives suffered. Perhaps the worst area of conflict was in the salmon canning industry, which had flourished in Oregon and Washington before migrating to Alaska in 1878. Alaska's first two canneries were founded at Klawock and Sitka, and in the years that followed their establishment, civilian and military authorities made no effort to prevent the takeover of the most productive salmon habitat by packing companies based in Washington, Oregon, and California. This was first accomplished by the direct appropriation of clan-owned fishing streams, and later by the widespread installation of company-owned fish traps. Aspects of Federal policy also tended to be anti-Native. Within a few years of the Alaska Purchase, for example, Congress exempted Natives from a prohibition on the fur seal harvest. This exemption, while positive for the long-term health of the fur seal population, was not principally intended for the Natives' welfare; instead, it ensured that Pribilof Islands residents would legally be able to conduct the annual harvest. And because the Bureau of Fisheries and successor agencies provided the workers less than adequate compensation, a form of indentured servitude took hold there over the next several decades. [6]

C. The Lure of Gold and the Non-Native Population Influx

Slowly, the appearance of new business opportunities began to debunk the old stereotypes. On the Pribilof Islands, for example, the harvesting of fur seals proved so profitable that within a few years the U.S. Treasury had been repaid Alaska's $7.2 million purchase price. Of more wide-ranging importance was the discovery of gold, in August 1880, along Gastineau Channel in southeastern Alaska, and by 1882 Juneau and nearby Douglas were thriving gold camps. Word soon leaked out that gold prospects lay on the far side of Chilkoot Pass, and in 1880 a group of prospectors obtained permission from the Chilkat Indians to gain access over the Chilkoot Trail. The wide-ranging prospectors, before long, found gold in paying quantities in various parts of the Yukon River drainage, and word of those discoveries brought a heightened level of prospecting activity. By 1895 a major gold camp had been located at Fortymile, just east of the Canada-U.S. border, and at Circle, 208 miles downstream from Fortymile. And everywhere the prospectors ventured, they impacted the local Native populations: by hunting, by tree cutting, and by providing Natives with wage-based jobs in mines or wood camps.

The year 1896 witnessed the first of three gold strikes that transformed the north country. The Klondike gold discovery, in August of that year, brought tens of thousands of Argonauts from the far corners of the world to the Yukon and Klondike river valleys, primarily in 1897 and 1898. No sooner had that rush begun to fade than gold was discovered on the Seward Peninsula, and tens of thousands more rushed to Nome and other nearby gold camps. Finally, a major gold strike took place in the Interior of Alaska in August 1902, and by 1905 Fairbanks was a full-blown gold camp.

These strikes, and other discoveries made in their wake, transformed Alaska demographically. By 1900, for example, the U.S. Census claimed that Alaska had more white than Native inhabitants, although the number of whites and Natives remained fairly similar as late as the eve of World War II. [7] (See Table 1-1, page 5) More important to Native lifeways, however, the scattered distribution of gold camps meant that prospectors (and to a lesser extent other non-Natives) were interacting with Natives throughout the territory. Non-Natives, it appeared, were thrusting themselves into economic enterprises in the most remote corners of the territory, and everywhere they went they began to impact the Natives' long-established lifeways.

Table 1-1. Population of Alaska and Selected Areas, 1890-2000

| Alaska (total) |

Non- Native | Native | Native % of Total |

Anchorage (a) |

Fairbanks (b) |

Juneau (c) | Ketchikan (d) |

A/F/J/K as % of Total |

Kenai Peninsula (e) |

Mat-Su Area (f) | # Non- Rural (g) |

% Non- Rural (g) |

|

| 1890 | 32,052 | 8,521 | 23,531 | 73.4% | 0 | 0 | 1,253 | 40 | 4.0% | 480 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 1900 | 63,592 | 36,555 | 27,037 | 42.5% | 0 | 0 | 1,864 | 459 | 3.6% | 728 | 0 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 1910 | 64,356 | 39,025 | 25,331 | 39.4% | 0 | 3,541 | 1,644 | 1,613 | 10.6% | 1,692 | 677 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 1920 | 55,036 | 28,478 | 26,558 | 48.3% | 1,856 | 1,155 | 3,058 | 2,458 | 15.5% | 1,851 | 715 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 1929 | 59,278 | 29,295 | 29,983 | 50.6% | 2,277 | 2,101 | 4,043 | 3,796 | 20.6% | 2,425 | 876 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 1939 | 72,524 | 40,066 | 32,458 | 44.8% | 3,495 | 3,455 | 5,729 | 4,695 | 24.0% | 3,002 | 2,366 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 1950 | 128,643 | 94,780 | 33,863 | 26.3% | 11,254 | 5,771 | 5,956 | 5,305 | 22.0% | 4,699 | 3,534 | 11,254 | 8.7% |

| 1960 | 226,167 | 183,645 | 45,522 | 18.8% | 44,237 | 13,311 | 6,797 | 6,483 | 31.3% | 9,053 | 5,188 | 66,622 | 29.5% |

| 1970 | 302,853 | 252,248 | 50,605 | 16.7% | 102,994 | 30,618 | 13,556 | 10,041 | 51.9% | 15,836 | 6,509 | 148,410 | 40,0% |

| 1980 | 401,851 | 337,748 | 64,103 | 16.0% | 174,431 | 53,983 | 19,528 | 11,316 | 64.5% | 25,282 | 17,816 | 231,605 | 57.6% |

| 1990 | 550,043 | 464,345 | 85,698 | 15.6% | 226,338 | 77,720 | 26,751 | 13,828, | 62.7% | 40,802 | 39,683 | 312,032 | 56.7% |

| 2000 | 626,932 | 528,889 | 98,043 | 15.6% | 260,283 | 82,840 | 30,711 | 14,070 | 61.9% | 49,691 | 59,322 | 349,377 | 55.7% |

NOTES:

(a) — includes Anchorage Borough (1970), Municipality of Anchorage (1980 through 2000).

(b) — includes Fairbanks North Star Borough (1970 through 2000).

(c) — includes Greater Juneau Borough (1970 through 1990), Juneau City and Borough (2000).

(d) — includes Ketchikan Gateway Borough (1970 through 2000).

(e) — includes Kenai census district (1910-20); Kenai, Seldovia, and Seward census districts (1929-39); Homer, Seldovia, Seward, and a portion of the Anchorage census district (1950); Kenai-Cook Inlet and Seward election districts (1960); Kenai Peninsula Borough plus Seward Census Division (1970), and Kenai Peninsula Borough (1980 through 2000).

(f) — includes Cook Inlet census district (1910); Cook Inlet and part of Knik census districts (1920); Talkeetna, Wasilla, and part of Anchorage census districts (1930); Palmer, Talkeetna, Wasilla, and part of Anchorage census districts (1940); Palmer, Talkeetna, and Wasilla census districts (1950); Palmer-Wasilla-Talkeetna election district (1960), and Matanuska-Susitna Borough (1970 through 2000).

(g) — Non-rural population and percentages are based on the populations of individual cities, towns, and identified unincorporated areas—not boroughs—that total 7,000 people or more.

Along the coast, similar impacts were taking place because of the booming salmon-canning industry. After its founding in 1878, the industry quickly grew along Alaska's shoreline, and by the mid-1890s more than 50 canneries dotted the coast between Southeastern Alaska and Bristol Bay. Wherever the canneries were built, the lifestyles of local Native populations were transformed. This transformation took place for two reasons: some succumbed to the lure of fishing and cannery jobs, while others, all too often, were affected because of the depletion of the fisheries resource.

The federal government was by no means a passive player in the transformation of the Natives' culture. In 1884, as part of the first Organic Act, language was inserted to "make needful and proper provision for the education of children of school age in the Territory of Alaska, without reference to race." The implication of racial equality was mostly honored in the breach; for every town that had a substantial white population, the Bureau of Education operated separate white and Native schools. That separation was enhanced in 1905 when Congress passed the Nelson Act, which authorized whites living in any "camp, village, or settlement" to petition for their own school district; this act, in a short time, left the Bureau of Education as almost the sole educator of Alaska's Natives. The per-capita funding of Bureau of Education schools was typically far poorer than in white schools, and as time went on, the funding gap became more pronounced. [8]

More appropriate to this study, however, was the Bureau's policies toward its educational facilities. One policy, similar to a long-established practice of the Bureau of Indian Affairs outside of Alaska, and also that of the many religious denominations that had been educating Alaska Natives since the 1880s, was that the most efficient way to educate Native children was to remove them from their households. As part of the prevalent assimilationist policy, parents typically signed away their daughters until age 18 and their sons until age 21; some children went to village day schools, while others headed off to remote boarding schools. Both venues adopted a similar regime; Natives were asked to aspire to white values and were required to speak English to the exclusion of all other tongues. Under this system, most Natives were educated poorly at the various village day schools. Only a select few went to high schools, either in the larger towns or outside of Alaska. The policy of the Bureau of Education and its post-1930 successor, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to establish schools in some Native villages but not others played a major role in the centralization of Native villages. [9]

Prior to the white man's coming, Alaska Natives had a diversity of residential patterns. Some lived in year-round villages; some had primary residences in villages, but headed out to summertime fish camps or carried out other itinerant activities; and still other Natives were so dependent upon seasonal migration patterns that no home was considered more permanent than any other. But intrinsic to Europeans was the concept of commercialization, and the Natives' participation in that concept—sometimes in a voluntary fashion, at other times enforced—demanded an increased reliance on permanent villages and a reduction in the number of those villages. The imposition of the Russian Orthodox Church, and other Christian denominations during the post-1867 period, reemphasized these patterns. As a result of these processes, most Alaska Natives were settled in permanent villages by the late 1930s. But some Natives continued to follow an itinerant lifestyle, and in a number of instances—such as at Anaktuvuk Pass, Lime Village, and Sleetmute—permanent settlement did not take place until several years after the conclusion of World War II. [10]

|

|

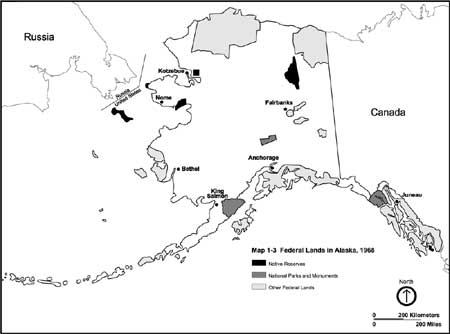

Map 1-3. Federal Lands in Alaska, 1968.

(click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

|

D. Federal Policies Toward Alaska's Natives, 1890-1950

Central to the government's Indian policy on a nationwide basis was the reservation system. The country's first Indian reservation had been established during the 1840s, and by the late nineteenth century the reservation was the primary vehicle by which the government classified Natives and their land base. In their ideal state, reservations existed to protect tribal members from non-Native incursions, guarantee tribal identities, and provide welfare and assistance programs. All too often, however, the federal government used reservations as a vehicle to subjugate and segregate Natives from the larger society. Once formed, reservations were often whittled down to a small fraction of their former area, and on many reservations, commonly-owned lands were given over to individual families and then sold to non-Natives. The government also used its trust responsibility toward Native tribes to convert them from a nomadic to an agricultural existence; to educate them in the white man's ways; and to ensure their conversion to Christian beliefs and a reliance on the English tongue. [11]

|

| Natives groups have been fishing Alaska's waters for thousands of years. This early twentieth century dipnetting scene was taken along the Copper River. NPS (WRST) |

Most Alaska Natives were spared the reservation experience, primarily because Alaska's first General Agent for Education, Sheldon Jackson, did not believe in them. Governor John Brady, a friend of Jackson's and of a similar mind, wrote that "the reservation policy [in the western United States] has not worked well and has wrought mischief. It would not be good policy to introduce it to Alaska, where the [Native] people are self-supporting and of keen commercial instincts." But William Duncan, another person prominent in southeastern Alaska affairs, disagreed. Duncan, an Anglican priest at a Tsimshean village in northern British Columbia, decided in 1886 to take his flock elsewhere. Casting about for a location in Alaska, he contacted Congressional representatives. Worried that his flock might fall prey to "saloons and other demoralizing institutions," he urged Congress to set aside a tract of land at least five miles from the nearest white town. That body, in response, agreed to allow him and his parishioners to move to Annette Island, south of present-day Ketchikan. In accordance with Duncan's wishes, Congress in 1891 established the Metlakatla Indian Reserve, which included all of Annette Island. This reservation, now known as Annette Island Indian Reservation, turned out to be an anomaly; it was, in practical terms, Alaska's only Congressionally-designated Native withdrawal. [12]

Since the 1890s, various federal departments have moved to establish variants on the reservation system. As part of his concern about the "betterment" of the Native population, for example, Sheldon Jackson played a major role in the establishment of a series of reindeer reserves in northwestern Alaska. Then, from 1905 to 1919, he successfully lobbied the Interior Department's Office of Education to establish an additional fourteen Alaska Native reserves. These reservations, which ranged in size from 17 acres (Chilkat Fisheries Reserve) to 316,000 acres (Elim Reserve), were called executive order reserves and were created with the express purpose of developing Native economic self-sufficiency. Congress, in 1919, passed a law prohibiting the creation of additional "Indian" reserves except by Act of Congress. The Secretary of the Interior, however, circumvented the law by establishing several "public purpose reserves" in Alaska that were de facto Native reserves. Between 1925 and 1933 the Secretary created five such reserves, which ranged in area from 110 acres (Amaknak Island, near Unalaska) to 768,000 acres (Tetlin). Beginning in 1934, a new lands concept came into vogue when Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act. Harold Ickes, Franklin Roosevelt's Secretary of the Interior, seized upon Section 2 of the act and, in response to appeals from various Alaska Natives for protection from non-Native interests, created the first two "IRA reserves" in 1943. (These were the Venetie Reserve and the Karluk Fishing Reserve.) During the next six years four additional reserves were established. No new reserves for Alaska's Natives were established between 1949 and the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971. [13]

The IRA reserves, and the two forms of executive reserves that preceded them, were limited in their application and less than fully welcomed by those whom they were ostensibly created to protect. The various reserves that were created in the early- to mid-twentieth century were established under the best of intentions, and many succeeded in their purported purpose. But many Natives, not wanting to be classified as "reservation Indians," actively fought the inclusion of their lands into reserves, and in several cases they were successful in having the withdrawals repealed. [14] The creation of the various reserves, moreover, appears to have had little if any effect on educational funding or other measures of governmental assistance, and it appears that the residents of most Native villages were never included in a reservation and had few regrets about that state of affairs.

Early in the period in which the Federal government toyed with the idea of limited reservations (either Native reserves or IRA reserves), Congress also provided a basis for Natives to own land on an individual basis. In 1906, it passed the Alaska Native Allotment Act, which was a modification of the General Allotment Act of 1887. The 1906 act authorized the Interior Secretary "to allot not to exceed one hundred and sixty acres of nonmineral land ... to any Indian or Eskimo of full or mixed blood who resides in and is a Native of said district ... and the land so allotted shall be deemed the homestead of the allottee and his heirs in perpetuity." Potential allottees needed to show only minimal evidence of use and occupancy. This act, which was the product of enlighted policymaking, was a clear attempt to give Natives a legal device that prevented their expropriation by non-Native trespassers, and it further underscored the government's conviction (in the words of legal scholar David Case) "that traditional reservation policies did not suit the semi-nomadic lifestyles practiced by the majority of Alaska's Natives." [15]

|

| Subsistence fishers in northwestern Alaska during the summer of 1974. NPS (ATF Box 10), photo 4464-28, by Robert Belous |

Although the federal government's half-hearted attempts to educate Natives and place them on reservations often had deleterious impacts, the government did make an honest effort to aid Alaska's Natives when it came to fish and game regulation. Generally speaking, few strictures were placed on Native fish and game harvesting; and Natives were specifically exempted from such fish and game laws as the Alaska Game Law of 1902, the White Act of 1924, and the Alaska Game Law of 1925. [16] (The White Act was the basic act governing the salmon fisheries until statehood.) The U.S. Supreme Court, in the landmark Hynes v. Grimes Packing Company decision, made it clear that White Act provisions did not explicitly grant a preference to residents of Alaska's ad hoc Indian reserves. But when resources did conflict, federal agencies sometimes intervened on behalf of rural users, both Native and non-Native. About 1920, for example, the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries barred the Carlisle Packing Company from establishing a floating cannery along the lower Yukon River because it feared that the cannery would capture fish normally harvested by upriver subsistence users. [17]

During the territorial period, the Federal government played a dominant role; the Territorial legislature, by contrast, had limited powers to regulate Alaskan affairs, though the extent of those powers slowly broadened over the years. Both Natives and non-Natives during this period were able to pursue fishing for personal-use purposes with few restrictions. Fishing licenses were first instituted in 1942, and from then until statehood, non-Natives paid just $1 per year for a license while "native-born Indian or Eskimo" fishers were not required to purchase one. [18] While the Fish and Wildlife Service created specific seasons and bag limits for "game fish" in the most heavily populated areas of the territory, the harvest of salmon for personal uses remained unregulated until the 1950s, when modest restrictions were imposed for Resurrection Bay and a few streams in the Anchorage area. [19]

In 1949, Alaskans got their first real voice in territorial fish management when the legislature established the Alaska Department of Fisheries; for the next ten years, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service asked the Alaska Fisheries Board—all of whom were Alaska residents—to provide input on a wide range of management actions. One of the first issues the board addressed was the establishment of an equitably applied personal use fishery. A major problem, at the time, was that some residents were harvesting large quantities of fish just before or after the legal season; they used commercial equipment but claimed that they were harvesting for their personal use. To overcome these perceived abuses, board members toyed with the idea of prohibiting the use of commercial gear during the 48-hour period surrounding each legal season. [20] But the board was unable to convince Fish and Wildlife Service authorities to establish such a provision; limits on personal-use salmon harvesting, moreover, were never implemented during the territorial period.

Throughout this period, Natives in most of Alaska had only a tenuous relationship to the prevailing non-Native commercial sector. Moreover, they were isolated from each other and physical interaction was difficult. For all of these reasons and more, Natives in most of Alaska were poorly organized outside of local trading and kinship networks.

Exceptions to this generalization arose in Interior and southeastern Alaska. By the early twentieth century, many Interior Athapaskans—particularly those living along the Yukon or Tanana rivers—had been interacting with non-Natives for years, particularly during the Klondike gold rush and its aftermath. In 1912, various village leaders met and established the Tanana Chiefs Conference. The organization is now more than 85 years old; since the 1971 passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, TCC has served as the non-profit arm of Doyon, Ltd., the regional corporation for much of Interior Alaska. [21]

Southeastern Alaska Natives organized during the same period and for similar reasons. These Natives, most of whom were Tlingit, Haida, or Tsimshian Indians, had by the early twentieth century been exposed to more than a century of Russian or Anglo acculturation, and many were tied, at least in part, to the predominant commercial economy—as fishermen, cannery workers, or in a wide variety of other occupations. In 1912, twelve Tlingits and one Tsimshian met in Juneau and formed the Alaska Native Brotherhood, a primary purpose of which was the recognition of Native citizenship rights. The ANB, in 1915, was joined by the Alaska Native Sisterhood, and chapters (called camps) of both organizations soon spread throughout southeastern Alaska. The ANB lobbied the territorial legislature for the realization of its goals, and in 1915 the legislature passed two laws favoring Natives: one enabled them to become citizens, while the other provided self-government to southeastern Native villages under certain conditions. In response to ANB pressure, Congress in 1924 granted citizenship to all Alaska Natives. By that time, the ANB and the ANS had assumed a broad mantle of new goals. Both organizations have remained active ever since. [22]

E. Statehood and its Ramifications

As noted above, the U.S. Census in 1900 first recorded that the Alaska non-Native population exceeded that of Alaska's Natives. The population of the two groups, however, was fairly similar, and as the twentieth century wore on it remained so; as late as 1939, Alaska's racial composition was approximately 54% white, 45% Native, and 1% from all other groups. But World War II brought a massive influx of non-Natives to support the war effort, and in-migration (primarily from the "lower 48") continued during the booming postwar years. Because of improved conditions, the Native population expanded, too, but by 1960 Natives comprised less than 19 percent of Alaska's population. [23] (See Table 1-1) New highways, airports, communications sites, oil drilling pads, and homesteads began to dot the landscape. The Anchorage and Fairbanks areas and the Kenai Peninsula witnessed the most profound changes, but to a lesser extent, life also began to change in the Alaska bush.

A major political movement in Alaska during the postwar period was the push for statehood. A statehood bill had first been submitted by Alaska's Congressional delegate back in 1916, but little momentum for statehood was generated until World War II. After the war, the informal team of Delegate E. L. "Bob" Bartlett and Governor Ernest Gruening applied pressure at every turn in the statehood cause. That cause was helped immeasurably by a referendum that was held on the subject in November 1946; in that vote, more than 58 percent of those who went to the polls favored statehood. The road to statehood proved long and arduous, however, and Congress did not pass a statehood bill until June 1958. Alaska officially became the 49th U.S. state on January 3, 1959. [24]

The Alaska Statehood Act stated clearly that all Alaskans should have equal access to the state's fish and game resources. Article VIII, Section 3 stated that "Wherever occurring in their natural state, fish, wildlife and waters are reserved for common use." Section 15 stated that "No exclusive right or special privilege shall be created or authorized in the natural waters of the State," and Section 17 read that "Laws and regulations governing the use or disposal of natural resources shall apply equally to all purposes similarly situated with reference to the subject matter and purpose to be served by the law or regulation." [25] Thus all Alaskans—rural and urban, Native and non-Native—had equal access to Alaska's fish and game resources. These statements would loom into ever-greater significance in future years as federal and state interests grappled over legal rights to the management of state resources. The ramifications of these jurisdictional tug-of-wars will be discussed in chapters 6 and 8.

In the minds of Alaska's Natives, statehood represented a new, ominous threat to the use of their traditional lands, because it set in motion a process by which millions of acres would be conveyed to state ownership. Prior to statehood, more than 99 percent of Alaska's land area was owned by the Federal government, and the provisions by which land could be secured for specific purposes (via homesteads, trade and manufacturing sites, Native allotments, Federal conservation withdrawals, etc.) were sufficiently narrow in their scope that the vast majority of Alaska outside of the southeastern panhandle was still open entry land. [26] Alaska's Natives—who lived and carried on subsistence activities on much of this land—were given mixed messages regarding their legal rights to it. Section 8 of Alaska's first Organic Act, passed in 1884, merely reiterated the status quo from the 1867 Alaska Purchase Treaty when it stated:

the Indians or other persons in said district shall not be disturbed in the possession of any lands actually in their use or occupations or now claimed by them but the terms under which such persons may acquire title to such lands is reserved for future legislation by Congress. [27]

Native interests, over the years, attempted to address the long-standing problem of aboriginal title through "future legislation," the first bill with that goal in mind having been introduced in 1940. Congress, however, sidestepped the question, both in 1940 and throughout the period leading up to statehood. [28] Section 4 of the Alaska Statehood Act made no move to quash that quest; it suggested a preference of Native subsistence rights over those of the proposed state when it noted that "said State and its people do agree and declare that they forever disclaim all right and title ... to any lands or other property (including fishing rights), the right or title to which may be held by any Indians, Eskimos, or Aleuts...." Indeed, a later court ruling explained that the act "would neither extinguish [aboriginal and possessory claims] nor recognize them as compensable." But the Statehood Act made no attempt to resolve the long-simmering question of aboriginal title; and more ominously, Section 6(b) of the same act permitted the new state to select up to 102,550,000 acres of "vacant, unappropriated and unreserved" public [i.e., federal] lands in Alaska. This acreage represented more than one-quarter of Alaska's land area—an area roughly the size of California. And regardless of where the state made its selections, the lands it chose would be impinging on areas that Natives had used from time immemorial. [29]

The statehood act, despite its failure to provide a land settlement, gave the state's rural residents (many of whom were Native) their first subsistence protections. Prior to statehood, such protections were largely unnecessary because neither residents nor Outside sportsmen exerted much long-term impact on game and fish stocks, except in the areas surrounding a few large towns. As AFN attorney Donald Mitchell noted in a hearing, years later, before the state legislature,

There was little [resource] pressure because there was such a small population in Alaska; there was not unacceptable levels of pressure on a lot of rural fish and game resources. ... and the federal statutes that controlled the regulation of fish and game were relatively liberal because they had no reason to be otherwise.

| Hugh Wade (left), Alaska's acting territorial governor in 1958, fought to ensure that Alaska's Natives would have a fair share of the new state's fish and game resources. William A. Egan (right) served as Alaska's first governor (1959-1966) and again from 1970 to 1974. ASL/PCA 213-1-2 |

During the late 1950s, the territorial legislature prepared for statehood in two significant ways. First, the 1957 legislature passed a bill (SB 30) that established the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and the Alaska Fish and Game Commission, and a key part (Section 5) of that bill provided for fish and game advisory committees. The establishment of a broad network of advisory committees offered local residents throughout Alaska the potential to affect Fish and Game Commission decision making. (The bill's immediate impact, however, was more apparent than real; by the end of 1958, most of the six active advisory committees were located in towns with relatively large, non-Native populations.) [30] The legislature also geared up for statehood by formulating a series of statutes that would provide the basis for regulations. One of those statutes dealt with Fish and Game regulation (which later became Title 16 under the State of Alaska's statutory system), but according to Mitchell's recollection, the legislature "somehow ... failed to include adequate provision to take care of the Native people that resided in rural Alaska that had a very large stake in fish and game resources." [31] But Alaska's acting governor at the time was Hugh Wade, a former area director of the Alaska Native Service, [32] and Wade reacted to the statute's passage by writing a letter stating "that there must have been some mistake" in omitting resource protection to Alaska's Natives. That letter was forwarded on to Washington, D.C. where it was introduced onto the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, and the thrust of Wade's letter eventually emerged as Section 6(e) of the Statehood Act. Section 6(e), according to Mitchell, "reserved to the federal government the authority to manage fish and game until such time as the Secretary of the Interior certified that the Alaska Legislature had submitted a proposal for the adequate management of Alaska's fish and wildlife resources." [33]

In 1959, the newly-minted state legislature—recognizing that the federal government held a de facto veto pen over Alaska's fish and game statutes—adopted a fish and game statute (Title 16) that distinctly defined the difference between sport and subsistence fishing. This statute, which was to be administered by the Alaska Board of Fish and Game, became effective in 1960. [34] It defined fishing according to gear type; subsistence fishing was defined as a personal-use activity that relied on gill nets, seines, fish-wheels and similar gear, [35] while sport fishing implied a hook-and-line harvesting method. In accordance with this distinction, subsistence users were required to obtain a permit and to submit harvest records to the Department of Fish and Game, and separate subsistence regulations were included in the state's first-ever commercial fishing regulations booklets. [36] Separate classifications, however, did not imply a preference for subsistence fishing over sport or commercial fishing, and urban residents were free to engage in subsistence fishing. In regard to hunting, the statute made no distinction between subsistence and sport harvests. [37]

F. Toward a Land Claims Settlement

Not long after Alaska became a state, officials in the new government began to organize, evaluate, and select appropriate lands as part of their Congressional allotment. And predictably, several of those selections brought protests from rural residents (primarily Alaska Natives) whose traditional use areas were being jeopardized. By 1961, state officials had already selected and filed for more than 1.7 million acres near the Tanana village of Minto. In response, the Bureau of Indian Affairs that year filed protests on behalf of the villages of Northway, Tanacross, Minto, and Lake Alegnagik for a 5.8 million-acre claim that included the recent state selections. More conflicts, it appeared, were sure to follow. [38]

Other threats to the Natives' traditional lands and lifestyle surfaced during the same period. Back in 1957, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission had conceived of "Project Chariot," a plan to explode a nuclear device at Cape Thompson, near the Inupiat village of Point Hope. [39] The AEC initially announced that the blast was needed to create a harbor that would be used for mineral shipments. Nearby villagers, however, denounced the project beginning in 1959 for two reasons: worries over atomic radiation and because the project was "too close to our hunting and fishing areas." In 1961, Inupiat artist Howard Rock was so moved by the AEC's high-handedness that he decided to publish a weekly newspaper, the Tundra Times, that would address Natives' concerns. Rock spearheaded a campaign against the proposed project, which the government was eventually forced to abandon. [40]

Another huge project was the Rampart Dam proposal, which would have inundated more than 10,000 square miles of the Yukon River valley from the Tanana-Rampart area to the Woodchopper-Coal Creek area, within today's Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. Planning for the project began shortly after statehood, and in 1963 it received a major impetus when U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening urged its construction. Natives were chagrined at the proposal and at Gruening, too, who proclaimed that the proposed dam would flood "only a vast swamp" that was "uninhabited except for seven small Indian villages." The battle over the dam raged for another four years. Finally, in June 1967, Interior Secretary Stewart L. Udall canceled the project, citing economic and biological factors as well as the drastic impact on the area's Native population. [41]

All of these impacts—the land claims process, Project Chariot, the Rampart Dam proposal, and other incidents (such as the protests that followed Rep. John Nusunginya's 1961 arrest for hunting ducks out of season) [42]—awakened Native leaders to the fact that only by organizing would they be able to have their collective voices heard. The first opportunity to organize came in November 1961, when the Association on American Indian Affairs, a New York-based charitable organization, convened a Native rights conference in Barrow that was attended by representatives from various coastal villages, some from as far away as the lower Kuskokwim River. A report prepared at the conference stated, "We the Inupiat have come together for the first time ever in all the years of our history. We had to come together.... We always thought our Inupiat Paitot [our homeland] was safe to be passed down to our future generations as our fathers passed down to us." Later that year, meeting representatives formed Inupiat Paitot, a new regional Native organization. [43]

Other Native organizations followed in short order. In 1962, the Tanana Chiefs Conference was reorganized to deal primarily with "land rights and other problems." During the next few years, Alaska Natives formed several new regional organizations, such as the Bristol Bay Native Association, primarily to press for a land claims settlement. In October 1966, representatives of the newly-formed groups met in Anchorage to form an Alaska-wide Native organization; this group was formally organized the following spring as the Alaska Federation of Natives. [44]

In the meantime, Natives on both an individual and collective level were attempting to provide form and substance regarding how the Federal government should resolve the land claims situation. In response to a land freeze request by a thousand Natives from villages throughout western and southwestern Alaska, Interior Secretary Udall in 1963 appointed a three-person Alaska Task Force on Native Affairs. The task force's report, issued later that year, urged the conveyance of 160-acre tracts to individuals for homes, fish camps, or hunting sites, the withdrawal of "small acreages" in and around villages; and the designation of areas for Native use (but not ownership) for traditional food-gathering activities. Natives, with the assistance of the Association on American Indian Affairs, flatly opposed the task force's recommendations and successfully fought their implementation. In the meantime, they lobbied the Congressional delegation for a more favorable land claims settlement. [45]

The land claims issue quickly crystallized on December 1, 1966 when Secretary Udall, by the first of a series of executive orders, imposed a freeze on land that had been claimed by various Native groups. Udall acted in response to a request from the newly-formed Alaska Federation of Natives; they, as Natives had been doing since 1963, had protested to the Secretary because the state, which had gained tentative approval to the ownership to hundreds of thousand of acres of North Slope land, had announced plans to sell potentially lucrative oil and gas leases for those properties. (What was "frozen" in the first executive order was potential oil-bearing acreage near Point Hope. [46] Commercially-viable quantities of North Slope oil and gas, at this time, had not yet been discovered, but drilling rigs had been moved to other North Slope properties and geologists were hopeful that new deposits would be located.) Because of Udall's action—which was soon applied to other North Slope tracts and extended to the remainder of the state's unreserved lands in August 1967—neither the state nor any private entities could secure title to any land that had been subject to Native claims until Congress resolved the issue. As noted above, Natives by this time had already claimed title to large tracts in western and southwestern Alaska, and within a few months of Udall's action they had filed claims for some 380,000,000 acres—an area approximating that of Alaska's entire land area. [47] The State of Alaska, whose land selections were halted by the freeze, vociferously protested the Secretary's action. The land freeze remained, however, until Congress was able to resolve the issue through appropriate legislation. [48]

One important area of the state, it should be noted, was relatively unaffected by the Udall's executive orders. In southeastern Alaska, the overwhelming preponderance of land, by the mid-1920s, had already been withdrawn by the federal government, either for Tongass National Forest or Glacier Bay National Monument. Because this state of affairs gave Natives few opportunities to acquire their own acreage, Congress had first addressed land claim issues in the Tlingit and Haida Jurisdictional Act, passed on June 15, 1935. That act authorized a "central committee" of Natives in that region to bring suit in the U.S. Court of Claims to compensate them for federal lands from which aboriginal title had been usurped. In response, William Paul and other lawyers representing the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) filed a $35 million suit "for the value of the land, hunting and fishing rights taken without compensation." But other factors intervened, the lawsuit was sidelined, and in 1941 the ANB formed a separate entity—soon to be called the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indians of Alaska—to take up the cause. The case itself was filed by James Curry in 1947. After many delays, the Court of Claims decided on October 7, 1959 that the Tlingits and Haidas had established aboriginal title to six designated areas. [49] But it took another nine years—until January 19, 1968—for the court to award the Tlingit and Haida Indians of Alaska $7.55 million in monetary damages. Although the court awarded the plaintiffs less than one-fourth of the amount they had originally requested—an amount that Central Council president John Borbridge judged to be "grossly inadequate"—it also concluded that Indian title to more than 2.6 million acres of land in southeastern Alaska had not been extinguished. Eighteen months later, Congress passed a law that authorized the Tlingit and Haida Central Council to manage the proceeds of the judgment fund for the benefit of the Tlingit and Haida Indians. [50]

The stakes involved in the land-claims controversy rose dramatically in late 1967 and early 1968 when oil, in gargantuan quantities, was discovered on the North Slope. Most if not all of the land above the underground oil reservoirs, as suggested above, was either owned or had been selected by the State of Alaska. Further testing showed that the Prudhoe Bay field, in one geologist's opinion, was "almost certainly of Middle-Eastern proportions." Optimism about the field's potential ran to such Olympian heights that a state oil-lease sale, held in Anchorage in September 1969, brought in more than $900 million in bonus bids. [51] The rush was on.

But the oil, valuable as it was, benefited no one unless it could reach outside markets, and to provide a transport mechanism an oil-company consortium called the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, in late 1969, applied to the Interior Department for a permit to construct a hot-oil pipeline from Prudhoe Bay to the port of Valdez on ice-free Prince William Sound. Interior Department approval was necessary because the proposed pipeline right-of-way, and the proposed North Slope haul road, crossed hundreds of miles of federal lands. Secretary Hickel, well aware of the land claims controversy, favored the pipeline, and in early March 1970 he was on the verge of issuing a permit for construction of the haul road. But on March 9, five Native villages, one of which was Stevens Village, sued in district court to prevent the permit from being issued, citing claims to the pipeline and road rights-of-way. In response to that suit, Judge George L. Hart issued a temporary injunction against the project until the lands issue could be resolved. [52]

By the time Judge Hart made his decision, Congress had been grappling with the land claims issue for more than three years. The issue had been the subject of at least one task force, a Federal Field Committee report, an Interior Department proposal, several Congressional bills and legislative hearings. But opposition from mining and sportsmen's groups, plus the widely divergent views of various key players, had slowed progress toward a mutually acceptable solution. Hart's decision, however, forced the powerful oil companies to lobby for a resolution to the lands impasse, and the path toward a final bill gained new momentum. [53]

The stage was set for Congress to act. The path toward a land claims bill would be long and tortuous, and a final bill—the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act—would not emerge until December 1971. The details of that act, and its implications on National Park Service policy in Alaska, will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Notes — Chapter 1

1 Joan M. Antonson and William S. Hanable, Alaska's Heritage, Alaska Historical Commission Studies in History No. 133 (Anchorage, Alaska Historical Society, 1985), 45; Michael E. Krauss, "Native Peoples and Languages of Alaska" (map), (Fairbanks, Alaska Native Language Center), 1982.

2 David S. Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, revised edition (Fairbanks, Univ. of Alaska Press, 1984), 6.

3 Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 6, 57-58.

4 Ted C. Hinckley, "Alaska Pioneer and West Coast Town Builder, William Sumner Dodge," Alaska History 1 (Fall, 1984), 7-19; Frank Norris, North to Alaska; An Overview of Immigrants to Alaska, 1867-1945, Alaska Historical Commission Studies in History No. 121 (Anchorage, AHC, June 1984), 2-8.

5 Robert H. Keller and Michael F. Turek, American Indians and National Parks (Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 1998), pp. 18-19; James A. Henretta, et al., America's History, third edition (New York, Worth Publishers, 1997), 127, 176, 182.

6 Thomas A. Morehouse and Marybeth Holleman, When Values Conflict: Accommodating Alaska Native Subsistence, Institute of Social and Economic Research, Occasional Paper No. 22 (June 1994), 11; Steve Langdon, "From Communal Property to Common Property to Limited Entry: Historical Ironies in the Management of Southeast Alaska Salmon," in John Cordell, ed., A Sea of Small Boats (Cambridge, Mass., Cultural Survival, Inc., 1989), 308-09, 320-21. The long history of the Pribilof Islands fur seal harvest has been detailed in Dorothy Jones's Century of Servitude: Pribilof Aleuts Under U.S. Rule (Lanham, Md., University Press of America), c. 1980.

8 Donald Craig Mitchell, Sold American; the Story of Alaska Natives and Their Land, 1867-1959 (Hanover, N.H., University Press of New England, 1997), 90-92. Annual reports by the Governor of Alaska to the Secretary of the Interior between 1910 and 1930 typically decried the deplorable conditions and funding shortfalls in the Bureau of Education schools, but little was done to remedy the situation.

9 Mitchell, Sold American, 94-96.

10 Theodore Catton, Inhabited Wilderness; Indians, Eskimos, and National Parks in Alaska (Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1997), 173; Taylor Brelsford to author, January 18, 2002.

11 Henretta, America's History, 530-33.

12 Mitchell, Sold American, 177-78, 261-62; Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 87, 116. Congress also designated a small Native reserve at Klukwan (near Haines) in 1957 on land that had been withdrawn by executive order in 1913. In 1915, Alaska's delegate to Congress, James Wickersham, met with seven village chiefs in Interior Alaska, and because the recently-passed Alaska Railroad Act promised a major non-Native population influx, he urged them to petition for reservations around their communities. But the chiefs' spokesman replied that "We don't want to go on a reservation we want to be left alone." As it turned out, Wickersham's concerns were overstated; outside of the immediate rail corridor, the railroad brought only modest demographic and economic changes to Interior Alaska.

13 Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 87-107.

14 Mitchell, Sold American, 263-65; Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 90, 94-95, 104-05.

15 Case, Alaska Natives and American Law, 133-39.

16 Morehouse and Holleman, When Values Conflict, 11. This exemption, promulgated for either humanitarian reasons or perhaps because enforcement would have been a practical impossibility, remained because Natives, generally speaking, had but a slight impact on the resource base. Even so, some non-Natives resented the exemption. Agnes Herbert and A Shikári, in Two Dianas in Alaska (London, Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1909, pp. 81-82, 101-02) ruefully noted that "the natives are practically unrestricted as to time, numbers, or anything else in their wanton destruction of game, both great and small, throughout the country such policy is an error of judgment," and they sarcastically added that the Alaska Game Law was a "beautiful and beneficent arrangement which permits natives to kill game in and out of season."

17 Pacific Reporter, 2d Series, Vol. 785 (1989), p. 6; Bob King to author, email, October 6, 1999.

18 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Game Commission, Regulations Relating to Game and Fur Animals, Birds, and Game Fishes in Alaska, Regulatory Announcement 43 (Washington, June 1954), 3, 20. Natives were defined as those "of one-half or more" Indian or Eskimo blood.

19 US F&WS, Regulations Relating to Game and Fur Animals (June 1954), 6-7, 18-19. The regulations defined game fishes as grayling and various trout species.

20 Alaska Department of Fisheries, Annual Report No. 2 (Juneau, 1950), 12; ADF, Annual Report No. 3 (Juneau, 1951), 12.

21 Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 391.

22 Claus-M. Naske and Herman E. Slotnick, Alaska; a History of the 49th State (Grand Rapids, MI, Eerdmans, 1979), 198-99; Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 406-09.

23 Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 306.

25 As excerpted from L. J. Campbell, "Subsistence: Alaska's Dilemma," Alaska Geographic 17:4 (1990), 82.

26 G. Frank Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time": The National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 (Denver, NPS, September 1985), 61.

27 Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 61, 64.

28 Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 63.

29 Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 65, 69; Catton, Inhabited Wilderness, 184.

30 "Fish and Game/Boards and Commissions, Reading Files" [various], 1950-1981, Series 556, RG 11, ASA. The following advisory committees met during 1958: Gastineau Channel, Homer-Seldovia, Ketchikan, Metlakatla, Nelchina, and Petersburg.

31 Alaska House of Representatives, Special Committee on Subsistence, Draft Report of the Special Committee on Subsistence; History and Implementation of Ch. 151 SLA 1978, the State's Subsistence Law (May 15, 1981), 7-8.

32 Evangeline Atwood and Robert N. DeArmond, comp., Who's Who in Alaskan Politics; A Biographical Dictionary of Alaskan Political Personalities, 1884-1974 (Portland, Binford and Mort, 1977), 102.

33 Alaska House, Draft Report of the Special Committee, 8. In a December 20, 2001 note to the author, Ted Catton notes that the stipulations contained in Section 6(e) predated 1958 by eight years. The bill in the 81st Congress was S. 50; the provision was Section 5(g).

34 The one-year delay for the transfer of fish and game jurisdiction was due to the efforts of Rep. Alfred J. ("Jack") Westland (R-Wash.), who introduced the so-called Westland Amendment in 1957. Ted Catton to author, December 20, 2001.

35 The Session Laws of Alaska for 1960, Chapter 131, Section 4 defined subsistence fishing as "the taking, fishing for or possession of fish, shellfish, or other fishery resources for personal use and not for sale or barter, with gill net, seine, fish wheel, long line, or other means as defined by the Board."

36 For example, see ADF&G, Regulations of the Alaska Board of Fish and Game for Commercial Fishing in Alaska, 1960, 67. The state also considered subsistence uses as distinctive based on income levels. As noted in the March 22, 1963 Daily Alaska Empire (p. 1), the subsistence fishing license (which cost 25 cents per year) "could be purchased by a person who has obtained or is obtaining welfare assistance or has a gross family income of less than $3,600 per year." This income ceiling remained until 1980, when it was raised to $5,600.

37 Alaska House of Representatives, Draft Report of the Special Committee on Subsistence (1981), 12; Campbell, "Subsistence: Alaska's Dilemma," 82. The new regulations, which also provided for the system of fish and game advisory committees that had been established two years earlier, had the potential to allow a broad spectrum of fish and game decision making. But most of the early committees were formed in urban, non-Native areas, and urban sportsmen's groups—backed by the urban advisory committees that represented them—played a far more active role in fish and game decision making than did the individual or collective voices of rural residents. State of Alaska, Session Laws, Resolutions, and Memorials (Juneau, 1959), 91; ADF&G, 1959 Annual Report, Report #11 (Juneau, 1959), 7; "Fish and Game/Boards and Commissions, Reading Files" [various], 1950-1981, Series 556, RG 11, ASA.

38 Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 64-65; Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 209-10. To defend their rights, the Minto people hired attorney Ted Stevens, who had just stepped down from a long tenure with the Interior Department Solicitor's Office. Stevens, then in private practice, offered his services on a pro bono basis. Six years later, Governor Walter Hickel would appoint Stevens to the U.S. Senate, a position he still holds.

39 During this period, nuclear explosions were by no means unheard of. Detonations had been taking place at Bikini Atoll, in the U.S. Marshall Islands, from 1946 to 1954; and on Amchitka Island in the Aleutian chain of Alaska, nuclear tests would take place in 1965, 1969, and 1971. In addition, many underground explosions took place.

40 Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 65-66; Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 205-08.

41 Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 65-66; NPS, The Alaska Journey; One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Department of the Interior in Alaska, 30-31; Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 211.

42 This incident is covered in greater detail in Chapter 8, Section M(4).

43 Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 207-08. As David Case notes (pp. 396-97), the Inupiat Paitot lasted only a short time. In 1963, Inupiats formed a new organization, the Northwest Alaska Native Association, which lasted until the passage of ANCSA; then, to avoid confusion with the newly-formed NANA Regional Corporation, it changed its name to Mauneluk Association. In 1981, the spelling was changed to the more traditional Maniilaq Association.

44 Case, Alaska Natives and American Laws, 389, 391, 401; Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 66; Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 214.

45 Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 212; Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 66-67.

46 Donald Craig Mitchell, Take My Land, Take My Life; the Story of Congress's Historic Settlement of Alaska Native Land Claims, 1960-1971 (Fairbanks, University of Alaska Press, 2001), 132.

47 Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 214-15; Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 67; Thomas R. Berger, Village Journey; the Report of the Alaska Native Review Commission (New York, Hill and Wang, 1985), 23; Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska, Alaska Natives and the Land (Washington, GPO, October 1968), 440. Udall formalized the land freeze in Public Land Order 4582, which was issued on February 17, 1969.

48 In late 1968, given Richard Nixon's victory in the U.S. presidential race, Alaskans were hopeful that the land freeze might be lifted because Alaska Governor Walter Hickel, a freeze opponent, was nominated as the new Interior Secretary. Hickel initially stated that "what Udall can do by executive order I can undo." In order to gain Senatorial support for his nomination, however, he promised to retain the freeze until Congress could pass a land claims bill. Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 216; Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 67.

49 Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 202-03; Case, Alaska Natives and American Law, 380-81; Tlingit and Haida Indians of Alaska v. United States, 177 F. Supp. 452, 468 (Ct. Cl., 1959); Mitchell, Take My Land, Take My Life, 198, 213.

50 Anchorage Daily News, January 20, 1968, 1-2; Anchorage Daily News, January 20, 2002, F4; Rosita Worl, "History of Southeastern Alaska Since 1867," in Wayne Suttles, ed., Handbook of North American Indians: Vol. 7, Northwest Coast (Washington, Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 153-56.

51 NPS, The Alaska Journey, 95-96; Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 218-19, 237-38.

52 Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 219-20; Williss, "Do Things Right the First Time," 69.

53 Naske and Slotnick, Alaska, 214-22.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

alaska_subsistence/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2003