|

Alaska Subsistence

A National Park Service Management History |

|

Chapter 9:

THE SUBSISTENCE FISHING QUESTION

A. The Federal Role in Subsistence Fisheries Management, 1980-1992

As Chapters 5 and 6 noted, the federal government during the 1980s played a marginal role in the management of the state's game populations for subsistence purposes. Federal officials, to be sure, played a key role during 1981 and early 1982 in order to ensure that the State of Alaska's subsistence management program followed the guidelines that had been outlined in ANILCA and the subsistence management regulations. Between May 1982 and the end of the decade, federal officials were called upon, in the period following various court decisions, to clarify ANILCA's specific intent to state officials. Except for those periods, NPS officials played some role in interpreting game management regulations on NPS-administered lands, and officials representing other federal land management agencies also played a minor role on lands managed by those agencies.

But the federal government in general, and the NPS in particular, played almost no role during the 1980s in the management of fish populations for subsistence purposes. As had been true since the 1958 Statehood Act, Alaska's navigable waters were managed by the state. And of specific interest to the NPS, both agency officials and park-area subsistence users appeared to be far more interested in the management of game than fish populations. Perhaps as a result, there are few known instances in which NPS officials brought specific fish management issues before the state Fisheries Board. The various subsistence resource commissions, moreover, were excluded from any advisory role related to fisheries; when the Gates of the Arctic SRC made a fisheries recommendation to the Interior Secretary in May 1987, an Interior Department official responded that "the Commission's legislative authority is for hunting and that fisheries are not within that area of authority." [1]

The Alaska Supreme Court's ruling in the McDowell case in December 1989 (see Chapter 7) portended a major change in the federal government's role in fish management. In striking down the state's 1986 subsistence law, the court made no distinction between subsistence hunting and subsistence fishing. In the wake of McDowell, moreover, federal officials recognized that they might well be assuming the management of both fish and game resources on federal lands. Given six months in order to prepare for an assumption of subsistence management, Interior and Agriculture Department officials were able to cobble together a ten-week, two-stage public process in which the nature of federal management would be described and discussed. By June 1, officials had completed work on a "proposed temporary rule," and by the end of June a "final temporary rule" had been compiled and published in the Federal Register. The final rule laid out the regulations under which the federal government managed subsistence resources on Alaska's public lands for the next two years.

One major decision that emerged from the spring 1990 public process was that the federal government proposed a narrow, limited role over fisheries management. Both the June 8 and the June 29 regulations specifically excluded federal jurisdiction over navigable waters, which were defined as "those waters used or susceptible of being used in their ordinary condition as highways for commerce over which trade and travel are or may be conducted in the customary modes of trade and travel on water." Federal regulators explained their decision in this way:

There were many comments on the exclusion of navigable waters from the definition of public [i.e., federal] lands. ... There was a great deal of concern that the exclusion of navigable waters eliminated the majority of subsistence fishing, critical to the well being of rural communities. ... The United States generally does not hold title to navigable waters and thus navigable waters generally are not included within the definition of public lands.

Because Alaska's navigable rivers contained virtually all of the habitat in which fish were typically harvested for subsistence purposes, the practical effect of deciding on the above language was that the federal government continued to have minimal authority to manage the state's subsistence fisheries. Although the June 29, 1990 issue of the Federal Register spent many pages detailing subsistence fish and shellfish regulations, these pages were to a large extent ignored; because fishing activity was almost entirely limited to the navigable waterways, federal managers made few decisions in the fisheries arena for the next several years. [2]

As noted in Chapter 7, the federal government undertook a major assessment of its subsistence responsibilities during the 1990-1992 period when it compiled a draft and final environmental impact statement on the subject. The process that culminated in the final EIS included a 45-day public comment period and numerous public meetings. After the EIS was completed, federal officials issued a Record of Decision on April 6, 1992. On May 29, the federal government published final regulations on how subsistence activities would be managed on public lands.

The final regulations made no changes in the federal government's stance toward the management of fisheries for subsistence purposes. As noted in the May 29 Federal Register,

Numerous comments were received concerning the definitions of Federal lands and public lands. All of these comments focused on the issue of jurisdiction over fisheries in navigable waters. Many felt that the definitions should include navigable waters to protect subsistence use and the subsistence priority. They strongly believe it was Congress' intent to protect subsistence rights as broadly as possible. Additionally, many individuals commented that most subsistence resources are found in navigable waters.

The scope of these regulations is limited by the definition of public lands, which is found in section 102 of ANILCA and which only involves lands, waters, and interests therein title to which is in the United States. Because the United States does not generally own title to the submerged lands beneath navigable waters in Alaska, the public lands definition in ANILCA and these regulations generally excludes navigable waters. Consequently, neither ANILCA nor these regulations apply generally to subsistence uses on navigable waters. [3]

B. The Katie John Decision

Well before the government published its 1992 final rule on Alaska subsistence management, both federal officials and a broad spectrum of other interested individuals recognized that actions were taking place in the federal courts that had the potential to significantly broaden the federal government's role in the management of the state's subsistence fisheries. Court actions had begun during the mid-1980s, and by the time the final rule was published, a decisive case was ready to be ruled upon by a district court judge. [4]

The case, Katie John vs. the United States of America (known informally as the "Katie John case,"), had its origin in a longstanding quarrel over fishing rights. Batzulnetas, a longtime Ahtna village, was located along the banks of the swift, silty Copper River at the confluence of Tanada Creek, a clearwater stream. The site was thus "the perfect location for a fish camp," and for hundreds of years, area Natives harvested the sockeye salmon that ascended the drainage each summer. Batzulnetas remained an active seasonal village until the middle of the twentieth century; its last chief was Sanford Charlie, who died during the 1940s. After World War II, the village's residents resettled at Mentasta Lake and other year-round settlements accessible to the newly-developed highway system. But Batzulnetas, located not far south of Nabesna Road, continued to be widely used as a seasonal fish camp through the early 1960s.

In 1964, however, the Ahtnas' seasonal lifestyle was dealt a severe blow when the Alaska Board of Fisheries and Game shut down subsistence fishing (that is, fishing with nets and fishwheels) at Batzulnetas and other upriver fish camps. Fisheries managers did so because the Copper River, by this time, was supporting a wide array of commercial, sport, and personal-use fisheries, and state biologists posited (correctly or not) that if the Ahtnas caught too many fish in certain upriver "terminal streams," it would have disastrous effects, both on the various downstream users and on the viability of certain salmon stocks. After that decision, the village site was used less often, and before long, Batzulnetas was effectively abandoned. [5] And not long after that, the village and other area lands came under scrutiny by conservationists and Interior Department officials. In December 1978, President Carter included the former village site in Wrangell-St. Elias National Monument, to be administered by the National Park Service, and two years later, the old village was included as part of the 8.3 million acre Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. [6]

Although local Natives did not legally protest the state's 1964 fishing closure, many remained interested in the old village site. During the early 1970s a newly-established regional Native corporation, Ahtna, Inc., filed a 1,600-acre claim to the lands surrounding the village. Three local Native residents—Katie John, Doris Charles, and Gene B. Henry—filed claims to smaller parcels in and around old Batzulnetas. [7] None made an immediate attempt to resettle in the area, but by the early 1980s, Katie John and Doris Charles—two Ahtna elders residing in Mentasta Lake—"began talking about going back" to the former village site. The women may then have spoken to NPS officials about the situation. [8] In 1984, John and Charles traveled to Fairbanks and presented their case to the Alaska Board of Fisheries. The Board, however, voted 5 to 2 against their proposal; it suggested instead that they fish at various downstream sites—Slana, Chistochina, or Chitina—where subsistence harvesting was allowed. [9]

|

| Katie John near her fishwheel on the Copper River, 1994. Erik Hill, ADN |

The elders, however, persisted. (As John later noted, "We're Indian people and I don't like park rangers or game wardens coming in here telling us what to do like they own everything. That makes me mad. ... I don't want to be on somebody else's land. I like to do my fishing on my own land right there.") Hoping to gain fishing rights for herself, and for her grandchildren as well, she began talks with the Boulder, Colorado-based Native American Rights Fund (NARF), which was opening an office in Anchorage. Attorneys Robert T. Anderson and Lawrence Aschenbrenner, representing NARF, agreed in 1985 to file a lawsuit (Katie John vs. State of Alaska) on John and Charles's behalf. That suit, filed against the State of Alaska in U.S. District Court, requested that the residents of Dot Lake and Mentasta (i.e., where former Batzulnetas residents were now living) had the right to fish at the old village site. The fish board, in response to the suit, relented in 1987 and allowed locals, after obtaining a permit, to harvest a maximum of 1,000 sockeye salmon. The following year, the board further relaxed its rules and eliminated the salmon quota. But the women pressed on, still feeling that their rights were being curtailed. John and Charles, who by now were joined by the Mentasta village council, launched another District Court suit to allow continuous fishing and without the need for a permit. The plaintiffs were victorious in court, and by that fall they had won the right to a subsistence fishery that was continuously open from June 23 through October 1. But before the order could take effect, the December 1989 McDowell decision struck down the rural preference that Alaska subsistence users had previously enjoyed. The net result of the year's two court decisions was the creation of a subsistence fishery that included Batzulnetas in which all Alaskans could take part, regardless of their rural or urban residency. [10]

By July 1990, federal assumption of subsistence hunting was an accomplished fact, at least for the time being. Rural residents, as a result, once again had a statutory advantage in the harvest of game animals. But because fish populations in the state's navigable waters were still managed by state authorities, urban populations still had the same opportunities to harvest fish for subsistence purposes as their rural counterparts. Mentasta area residents felt that that system was unfair, so in September 1990, John and others petitioned the newly-established Federal Subsistence Board for reconsideration of the temporary regulations that applied to subsistence fishing at Batzulnetas. The Board, however, denied their request, based in large part on the fact that navigable waters did not fall within the definition of "public lands." [11]

Then, in early December 1990, the plaintiffs sought a judicial remedy. Three parties—Katie John, Doris Charles, and the Mentasta Village Council—challenged the federal government's recent decision that placed Alaska's navigable waters under state control. (This decision, as noted above, had been announced in the June 29, 1990 Federal Register.) The plaintiffs, backed by NARF, filed Katie John vs. United States of America in hopes of broadening the definition of "public lands" as noted in Section 102 of ANILCA to include navigable waters; and on a more pragmatic note, the plaintiffs also asked for a federal subsistence fishery in the Batzulnetas area. Named as plaintiffs in the suit were the federal government along with the Interior and Agriculture Department secretaries. [12]

The lawsuit was soon placed before U.S. District Court Judge H. Russel Holland. Fewer than sixty days after it was filed, federal attorneys analyzed the case and concluded that an additional defendant needed to be the State of Alaska, which managed the state's subsistence fisheries. [13] Soon afterward, state lawyers agreed to join the case; on the plaintiff's side, the Alaska Federation of Natives signed on in a supporting role. (After this point, state lawyers were the primary defendants, while federal solicitors took an increasingly neutral position.) The case was argued before Judge Holland in December 1991, but no decision was immediately forthcoming. Over the next two years the case ballooned in importance as a number of similar, ancillary suits—regarding subsistence fisheries management in Copper Center, Quinhagak, Stevens Village, and elsewhere—were consolidated into the Katie John case. [14] By 1993 the case had been consolidated with State of Alaska vs. Babbitt, in which Holland was also the deciding judge. [15]

A new wrinkle was injected into the fray in July 1993 when the Native American Rights Fund submitted a petition to the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior. That petition requested that the two secretaries include navigable waters within the definition of "public lands" as used in implementing Title VIII, and they were intended to validate the regulations pertaining to fish and shellfish that the federal government, on June 1, 1993, had issued for the 1993-1994 season. The secretaries made no immediate response to this petition; instead, they hoped that Judge Holland's court decision would clear up the murky waters surrounding this issue. [16]

In the fall of 1993, Judge Holland made the first of a series of preliminary findings in the Katie John case. In mid-November, according to a contemporary news report, he was "seriously considering arguments by state lawyers that federal subsistence management in the state was never intended when Congress passed [ANILCA]." More specifically, Holland was "tentatively of the opinion" that ANILCA provided little direction regarding whether the federal government had the power to take any subsistence regulation away from the state. State lawyers were "tentatively very happy" with the finding; they envisioned, at the very least, that subsistence fisheries rulings would continue to be enforced by ADF&G, and some people felt that Holland's remarks had presaged the disbanding of the federal government's entire, three-year-old subsistence management program. [17] But a second preliminary ruling, made two months later, was less favorable to the state's interests. Holland tentatively concluded that public lands as defined in ANILCA included both land and water. "Much of the best fishing is in the large navigable waterways where one has access to the most fish," he wrote. "By their regulations which exclude navigable waters from the jurisdiction of the Federal Subsistence Board, the Secretary abandoned to [the] state control of the largest and most productive waters used by rural Alaskans who have a subsistence lifestyle." The ruling, if finalized, promised to impose federal subsistence law on all of the state's navigable waters and make only rural Alaskans eligible for subsistence fishing rights under the Federal regulations. [18]

Given those preliminary rulings, Holland gave both sides in the case one last opportunity to present arguments. By this time the federal government, though a nominal defendant in the case, had largely stayed away from the fray. But when lawyers met on March 18, Justice Department lawyers—prodded by a their superiors in the Clinton administration—argued that federal law should apply on at least some of the state's navigable waters: specifically, on waters within national parks, wildlife refuges, and other designated conservation units. [19]

In his final ruling, however, Holland rejected the federal government's middle-of-the-road offerings and ruled strongly in favor of Alaska's Native groups. In a 42-page ruling issued on March 30 in Anchorage, Holland concluded (according to a local newspaper account) that "the needs of rural Alaskans aren't being met by current policies and that the federal government has the legal power and obligation to take over management of subsistence fisheries on all navigable waters." Using language similar to that initially used in his January 1994 preliminary ruling, he wrote that

By limiting the scope of Title VIII to non-navigable waterways, the Secretary has, to a large degree, thwarted Congress' intent to provide the opportunity for rural residents engaged in a subsistence way of life to continue to do so. Much subsistence fishing and much of the best fishing is in the large navigable waterways where one has access to the most fish....

[Therefore], the court concludes that the Secretary, not the State of Alaska, is entitled to manage fish and wildlife on public lands in Alaska for purposes of Title VIII of ANILCA. ... The court further concludes that the Secretary's interpretation of Section 102 is unreasonable. For purposes of Title VIII, "public lands" includes all navigable waterways in Alaska. [20]

In his decision, Holland declined to use the "reserved water rights" doctrine as a means of determining the geographic scope of Title VIII. (This latter doctrine would have provided an additional basis for federal jurisdiction over a navigable waterways in so-called "federal enclaves.") He did, however, invoke a more broadly-defined "navigational servitude" doctrine, which meant that a federal preference should apply to all navigable waters, including most rivers, lakes, and coastal waters inside the state's three-mile jurisdiction. (He noted that "even if navigational servitude is viewed as a power to regulate rather than as a property interest, Congress exercised that power to protect subsistence uses by rural Alaskans.") [21]

Native groups, not surprisingly, were elated by the decision. Hickel administration officials, by contrast, pronounced the judge's conclusion "incorrect." They vowed to appeal the decision to the Ninth District Appeals Court; as a stopgap measure, they intended to ask for a stay in the ruling until after the appeal had been decided. [22]

Soon after he made his decision, Holland agreed to the requested stay, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed to hear the case. [23] Meanwhile, federal bureaucrats acted to continue the validity of the fish and shellfish regulations. (Those regulations, as noted above, had been issued on June 1, 1993; they were valid for the 1993-1994 season, but they were set to expire on June 30, 1994.) Worried that "a lapse in regulatory control after July 1 could seriously affect the continued viability of fish and shellfish populations [and] adversely impact future subsistence populations for rural Alaskans," the Office of Subsistence Management issued an interim rule on June 27, 1994 that "effectively extends the existing regulations until December 31, 1995, ... or until the court [of appeals] directs the preparation of regulations implementing its order." The current fish and shellfish regulations, therefore, remained on hold pending the Court of Appeals' decision. [24]

That fall, the appeals court placed the state's appeal of Judge Holland's on a "fast track," and on February 8, 1995, three appeals-court judges heard oral arguments on the case in Seattle. By this time, state attorneys—who were backed in their effort by their counterparts in six other western states—had conceded that some of their previous opinions could not withstand the appeals process. State attorneys, therefore, argued that the subsistence priority granted by the federal government applied only to navigable waters on federal land, while attorneys representing Native groups, citing ANILCA language, argued that all of the state's navigable waters should be included under the subsistence preference. [25]

|

| In August 1995, the Alaska Supreme Court strongly upheld states' rights in the Totemoff case. Justices on the court that year included (left to right) Dana Fabe, Jay A. Rabinowitz, Robert L. Eastaugh, Allen T. Compton (chief), and Warren W. Matthews. Alaska Court System |

On Thursday, April 20, Senior Circuit Judge Eugene A. Wright of the Ninth U.S. Court of Appeals issued the long-anticipated ruling in the Katie John case. The 2-1 ruling, expressed in a nine-page opinion, supported some of Judge Holland's conclusions but rejected others. In a major victory for Native groups, the Ninth Circuit stated that Congress clearly intended the subsistence preference to apply to fisheries on navigable waters; federal intervention, the court noted, was needed because state subsistence policies had failed to protect villagers. As Judge Wright noted,

ANILCA's language and legislative history indicate clearly that Congress spoke to the precise question of whether some navigable waters may be public lands. They clearly indicate that subsistence uses include subsistence fishing. ... And subsistence fishing has traditionally taken place in navigable waters. Thus, we have no doubt that Congress intended that public lands include at least some navigable waters. [26]

In making that decision, the Circuit Court reversed two key decisions that the District Court had made a year earlier, namely about the reserved water rights doctrine and the navigational servitude concept. Specifically, the appeals court decision noted that "the definition of public lands includes those navigable waters in which the United States has an interest by virtue of the reserved water rights doctrine..." These waters, at a minimum, were those that ran through national parks, preserves, forests, and wildlife refuges, but they might include other federal lands as well. But the appeals court rejected the notion that the federal government had broader jurisdiction, because it noted that "the navigational servitude is not 'public land' within the meaning of ANILCA because the United States does not hold title to it." The court, in fact, admitted that "ANILCA's language and legislative history do not give us the clear direction necessary to find that Congress spoke to the precise question of which navigable waters are public lands," so it concluded by imploring, "let us hope that the federal agencies will determine promptly which navigable waters are public lands subject to federal subsistence management." [27] Given that task, Interior Department agency heads met just a day after the ruling to determine which waterways might be included. State lawyers, disappointed with the ruling, responded by asking for a stay of Wright's ruling. In addition, they promised that they would appeal the case yet again, to the U.S. Supreme Court if necessary. [28]

C. State and Federal Responses to Katie John, 1995-1999

On the heels of the Katie John decision, Alaskans—and their representatives in Washington—recognized that the federal government was going to assume the management of the subsistence fisheries on a major portion of the state's federal land unless some alternative could be worked out. Those who hoped to avoid federal assumption soon recognized that several possible solutions—some judicial, some legislative—were available. First, State attorneys could pursue judicial means to overturn the Katie John appeals court decision. Second, State attorneys could try to get the federal government out of the subsistence management arena by arguing that the fish and game management was a state, not federal function. Third, the Alaska legislature could pass a bill that would amend the state constitution so as to conform to ANILCA. Fourth, Alaska's legislators in Congress could push for the passage of a bill that altered ANILCA and eliminated the rural-preference provision. And fifth, Alaska's Congressional delegation could, through parliamentary means, delay the implementation of federal fisheries management until one of the other four options could be implemented. Each of these possible solutions was contemplated, and many were acted upon (sometimes repeatedly) between 1995 and 1999. A brief chronicle of these actions follows.

|

| Tony Knowles, the Governor of Alaska since 1994, has consistently supported the idea that the state should manage all of Alaska's fish and game resources; similarly, he has been a consistent supporter of having the Alaska legislature adopt a bill giving Alaska's voters the opportunity to vote on a subsistence-related amendment to Alaska's constitution. Office of Gov. Knowles |

|

| Fran Ulmer has served as Alaska's lieutenant governor since 1994. In 1995, she championed a "rural plus" proposal for bringing the state into compliance with the federal subsistence statutes; in addition, she has taken an active role in several task forces related to the subsistence issue. ADN |

One of the first major state actions, which was taken even before the Appeals Court rendered its verdict, was to withdraw from a case alleging that the state—not the federal government—was legally entitled to manage subsistence resources. As was first noted in Chapter 7, Hickel administration officials, in February 1992, had filed a suit (called Alaska vs. Lujan) that challenged the authority of federal agencies to take over subsistence management. District Court Judge Holland, in March 1994, had ruled against the state in this suit. (By this time the suit, now called Alaska vs. Babbitt, had been consolidated with Katie John vs. USA). Then, shortly after being sworn into office, Governor Tony Knowles announced his intention to drop the lawsuit. Many members of the Republican-dominated legislature were enraged by Knowles' action; they vowed that they would attempt to intervene in the case, and they hurriedly committed $20,000 to support a team of Washington lawyers who promised to represent them. But in early February 1995 the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the legislature's action, ruling that the legislature was "not empowered under state law to intervene in this appeal." [29]

As noted above, state lawyers responded to the April 1995 appellate-court decision in the Katie John case [30] by attempting to have it overturned. Their initial efforts, however, were less than successful. On August 8, the federal appeals court rejected the state's request for a reconsideration of the Katie John ruling. Given that rebuff, representatives from the state Attorney General's office got ready to appeal the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. State lawyers were heartened by a series of actions that took place in the months following Wright's decision. In August 1995, the Alaska Supreme Court's decision in the Totemoff case (Totemoff v. Alaska) "defiantly lays out the case for why all navigable waters fall under state jurisdiction," according to one news account. And four months later, a dissenting opinion in the Katie John appeal was made public; that opinion reiterated the need, first expressed in April 1995, to solve the fisheries dispute through the legislature, not the courts. [31]

Once the Katie John case was decided by the Ninth Circuit Court, the door remained open for the state legislature to produce a bill that recognized a rural subsistence preference and otherwise conformed to federal subsistence guidelines. [32] But the 1995 legislature, which was nearing the end of its regular session when the appeals court issued its ruling, made no particular efforts prior to its May 16 adjournment to pass a bill bringing subsistence management back to the state. (The legislature may have been hoping that the U.S. Supreme Court would overturn the appeals court ruling.) The appeals court, during this period, made no effort to assign a deadline for federal assumption of subsistence fisheries resources; instead, it deferred to the Supreme Court, which was expected to decide in the spring of 1996 if it would accept the Katie John appeal. Meanwhile, Governor Knowles hired Julian Mason as a mediator, who exerted some quiet diplomacy in hopes of creating some common ground between the disparate factions. [33]

Late in 1995, Governor Tony Knowles and his lieutenant, Fran Ulmer, began exploring new options to a federal takeover. Early in his administration, Knowles had made it clear that he would accept virtually any subsistence solution so long as it adhered to two basic principles: 1) that the state, not the federal government, should manage Alaska's fish and wildlife resources, and 2) the essential role of subsistence in the culture and economy of rural Alaska needed to be protected. [34] In early November, word leaked out that administration officials—hoping to solve the subsistence dilemma within these two parameters—had been quietly meeting with hunting and fishing groups; out of those meetings emerged a plan, spearheaded by Ulmer. That plan, which was unveiled on November 15, had three major tenets: 1) a concept called "rural plus," that guaranteed subsistence privileges both to rural residents and to those who had rural roots, 2) implementing changes to the Alaska Lands Act, and 3) amending the Alaska Constitution so as to conform with the Alaska Lands Act. [35] In response to criticisms of the plan, primarily by outdoor groups, Ulmer modified portions of her plan over the coming weeks. By early February 1996, she had completed a revamped plan—still in provisional form—and then pitched it to various interested parties. [36]

The major body to which she presented her plan, of course, was the Alaska State Legislature, which had begun its annual session in January 1996. But despite Ulmer's Herculean efforts, state legislators showed no particular inclination to move any subsistence bill that demanded changes to the Alaska constitution. Before long, the federal appeals court—still not knowing how the Supreme Court might act—ordered the Interior Department to begin the preparation of regulations for the assumption of fisheries management. It was widely anticipated at this time that the federal government would assume control over the subsistence fisheries later that year, perhaps in October. A federal assumption of fisheries management, however, would take place only if the Supreme Court refused to act.

This rough timetable was torn asunder on March 6 when Alaska's Congressional delegation moved to delay the process resulting in a federal fisheries assumption. Ted Stevens, a longtime member of the Senate Appropriations Committee, inserted a clause into an Interior Department spending bill that delayed any possible federal assumption until October 1, 1997. Interior Department official Deborah Williams protested the move, stating that it "directly contradicts the order of the 9th Circuit," and AFN President Julie Kitka echoed Williams' disappointment. Both, however, recognized that because of the power exerted by the Congressional delegation, little stood in the way of the provision becoming law. The delegation, by its action, hoped that the one-year moratorium would give the Alaska Legislature sufficient time to pass a subsistence bill that met federal guidelines. [37]

The provision, at the time, had no direct impact on Alaska fisheries management. But during the next two months, Stevens' action assumed a far higher level of importance. Several reasons buttressed that assumption. First, it became increasingly obvious that the subsistence compromise brokered by Lt. Governor Ulmer had failed because state legislative leaders refused to accept its provisions; the legislature, in fact, adjourned in early May 1996 without seriously addressing the issue. (A special session was held that year, but subsistence issues were not addressed during the thirty-day session.) [38] Another factor contributing to the heightened importance of Stevens' action was the U.S. Supreme Court's refusal, on May 13, to accept the state's appeal of the Katie John case. All parties now recognized that, with other options foreclosed, time was running out; unless some new action intervened, the federal government in October 1997 would be assuming control over much of Alaska's subsistence fisheries. [39]

|

| Ted Stevens, who has represented Alaska in the U.S. Senate since 1968, responded to the April 1995 decision in the Katie John case by giving the state legislature several opportunities to comply with subsistence guidelines as set forth in ANILCA. Office of Sen. Stevens |

Federal officials, in response to the appeal court's order, were already at work on drafting subsistence fishing regulations when Senator Stevens moved to delay the fisheries assumption date, and by late March 1996 a confidential blueprint of the draft regulations was aired to the press and public. State legislative leaders, fearing the worst, stated that the regulations called for the "total pre-emption of ... state management of fish and game resources." Interior and Agriculture Department officials, however, responded that they were simply following court orders and that the draft was subject to change before it was released to the public. Deborah Williams noted that "Our highest priority is to assist the state in the resumption of fish and game management. But right now we have to comply with the court orders. ... None of this is to be interpreted as the Department of the Interior seeking control of fisheries to the exclusion of giving the state the opportunity to do so." [40] The regulations, which were officially released to the public on April 4 as an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, were indeed broad in their scope. Because the regulations proposed a broad definition of waters where the federal government had "reserved water rights," the federal government was planning to assume control over subsistence fisheries on rivers adjacent to federal lands as well as those within federal lands, and it also outlined how federal agencies would limit commercial and sportfishing in state waters if such uses interfered with subsistence harvests. The public was given until June 14, 1996 to comment on the draft regulations. [41]

In order to give the public the opportunity to learn about and evaluate the regulations, federal bureaucrats scheduled nine public hearings during the public comment period; the first was held in Anchorage on May 13, the last in Fairbanks on May 28. The Anchorage meeting was attended by about 50 people, but only 18 spoke. Thirteen of those speakers, most of whom represented Native groups, favored the plan; AFN representative John Tetpon, for example, noted that "subsistence users cannot expect a fair hearing from the [state Fisheries Board] and they have in fact rarely gotten one ... Our dependence on the federal government to protect our way of life has been because they are our last resort." But the plan had three major critics: the Republican-led legislature, the Knowles administration, and the Alaska Outdoor Council. Assistant Attorney General Joanne Grace, one of those critics, complained that the plan "goes well beyond the priority that Congress actually granted ... and gives the Federal Subsistence Board authority that Congress did not intend it to have." And Attorney General Bruce Botelho said that it was "unworkable and highly offensive to the principles of state sovereignty" to propose limiting harvests on state lands in order to ensure adequate subsistence harvests on federal lands. But Interior Department representative Deborah Williams defended the plan; she noted, somewhat apologetically, that "There's not a single person in the Department of the Interior, to my knowledge, that wants to do this. But everyone realizes that in the absence of state action, we're required by law to do it." [42] By December 1996, Fish and Wildlife Service officials were "drawing up proposed fishing rules for public comment next summer" because they wanted to be ready to implement those rules, if necessary, by the October 1, 1997 deadline. [43]

By the fall of 1996, a broad spectrum of Alaskans recognized that the only realistic way in which Alaskans could forestall the federal assumption of subsistence fisheries management was for the Alaska legislature to pass a bill, signed by Governor Knowles, that would allow Alaskans to vote on an amendment to the Alaska constitution providing for a rural subsistence preference. [44] That vote by the state legislature would then have to be followed by its approval by a majority of Alaskan voters. As noted in Chapters 4, 5 and 6, Alaskans had voted on and approved a subsistence measure in the November 1982 election; during the 1978 and 1986 legislative sessions, moreover, the state legislature had approved subsistence bills. When polled on the subject during the 1990s, a strong majority of Alaskans—urban as well as rural—felt that the Alaska legislature should pass a subsistence bill that fit within ANILCA's framework so that Alaska's voters would at least have an opportunity to express their opinion on the subject. (By 1998, one poll showed that 90 percent of Alaskans wanted the chance to vote on the issue.) [45] That majority, however, was not reflected in the opinions of the Republican-dominated legislature. The legislature, dominated by urban interests and often described as conservative, seemed to have little interest in passing a subsistence bill that conformed to ANILCA; by its inaction, it prevented such a statewide vote from taking place.

That trait, for better or worse, continued during the 1997 legislative session. On May 12 the first session of the twentieth Alaska legislature adjourned without passing any measure—either the administration-backed resolution (HJR 10) or any other—that would have averted the assumption of subsistence management by federal authorities. The Knowles administration, recognizing that time was running out, began working with Alaska's Congressional delegation in hopes that minor changes in both state and federal law could avert a takeover. [46] By mid-June, the Congressional delegation had proposed several amendments to ANILCA, and on July 10, the "high-level task force" that Governor Knowles had convened [47] was urging the adoption of a plan that addressed the state constitutional issue. But problems immediately surfaced with both proposals; the Alaska Federation of Natives protested that the Congressional delegation's amendments were divisive and discriminatory, and the Alaska Outdoor Council—which backed a far different proposal—denounced the Knowles task force plan because it "asks Alaskans to forfeit equal protection without eliminating the discriminatory process that strips certain Alaskans of their inherent rights." [48] Knowles, still hoping to find a way to avert federal fisheries management, redoubled his efforts with the task force, but he was unable to persuade legislative leaders to hold a special session during the weeks that preceded the October 1 deadline. [49]

|

| Julie Kitka, president of the Alaska Federation of Natives since 1989, opposed tactics that delayed the implementation of the Katie John decision for more than four years. ADN |

During this period, federal officials reluctantly recognized that they might be assuming fisheries management on many of Alaska's navigable rivers despite the best intentions of both state and federal officials. As part of their planning effort, those officials had to decide whether the expansion of the federal subsistence program into the fisheries arena demanded the preparation of an environmental impact statement. Recognizing that federal subsistence managers had prepared a major EIS back in 1990-92, at the commencement of the federal program, officials tentatively decided that inasmuch as fisheries management was an expansion of an existing program, any impacts addressed by that expansion could be addressed in an environmental assessment (EA) rather than in an EIS. Based on this decision, federal subsistence officials went to work on the EA and completed it on June 2, 1997. The EA also concluded that "no significant impacts to fisheries resources and subsistence, sport or commercial fisheries would occur" with federal subsistence fisheries management. The two Secretaries promised to reassess the need for an EIS prior to the issuance of a Final Rule (i.e., a finalized set of subsistence fisheries regulations). [50]

By early September 1997, state leaders had apparently given up hope that a federal takeover could be averted prior to the October 1 deadline. But starting about September 15, Knowles and Babbitt began discussing the parameters of a possible delay, and given their concurrence, the two sought out Senator Ted Stevens in hopes of securing a second postponement of federal intervention. [51] Beginning on September 28, Stevens (who, by good fortune, served as the chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee) began meeting Knowles and Babbitt. After "two hard days of closed-doors bargaining," a deal was reached. Stevens was able to delay the deadline fourteen months, from October 1, 1997 to December 1, 1998; by the latter date, he postulated, there would be sufficient time for the Alaska legislature (given one last chance) to approve a constitutional amendment and also sufficient time for a statewide vote to be held on the issue. Because all parties agreed that it was in Alaska's best interest to have state law in conformance with ANILCA, the three parties agreed to two key ANILCA amendment proposals that served as "an inducement for a reluctant Legislature to act." These provisions, according to some observers, gave greater deference to the state in subsistence fish and game management. At Stevens' behest, they were slipped into an Interior Department appropriations bill, the passage of which—all parties recognized—was a "near-certainty." [52] Stevens announced the agreement with a note of finality: "This is probably the last thing we can do to give the state Legislature an opportunity to act. We'll just have to wait and see what the Legislature is going to do." Alaska Native leaders severely criticized the backroom nature of the last-minute negotiations; they stopped short, however, of opposing the overall agreement. [53]

Federal officials, who continued to use a carrot-and-stick approach during this period, made several moves during the months that preceded the Alaska State Legislature's 1998 session. As noted above, they had issued an "advanced notice of proposed rulemaking" related to subsistence fisheries management back in April 1996, and after a June 1996 deadline they had begun evaluating those comments in an attempt to formulate proposed regulations related to subsistence fisheries management. The Interior and Agriculture secretaries approved the results of that evaluation by December 4, 1997; eleven days later, the Proposed Rule on the subject was released to the public. The verbiage within that rule specified how the federal government intended to administer a fisheries management program. [54]

Many of the proposed regulations—regarding seasons and bag limits, methods and means of fishing—were in large part a duplication of existing state regulations. But in at least three specific subject areas, officials let it be known that the federal management system would be a departure from the status quo. First, regulations pertaining to customary trade were more broadly applicable in the proposed federal system than they were in the existing state-managed regime. Second, the new rules were specific regarding which waters federal authorities intended to manage. Federal agency heads, after weighing several alternatives, decided that they planned to manage 102,491 miles of inland waterways. [55] This alternative included "all navigable waters within the exterior boundaries of listed Parks, Preserves, Wildlife Refuges, and other specified units managed by the Department of the Interior and all inland navigable waters bordered by lands owned by the Federal government within the exterior boundaries of the two National Forests." [56] This alternative was chosen because "it would fully implement the Ninth Circuit's ruling while avoiding the serious management difficulties that would arise from checkerboard jurisdiction over segments of rivers within Department of Interior Conservation System Units...". The third change pertained to those lands and waters that were not placed under federal jurisdiction, and it was a reiteration of language that had first been included in the agreement that Stevens, Knowles, and Interior Department officials had worked out in September 1997. These proposed ANILCA amendments would clearly specify that the Secretaries are "retaining the authority to determine when hunting, fishing or trapping activities taking place in Alaska off the public lands interfere with the subsistence priority on the public lands to such an extent as to result in a failure to provide the subsistence priority and to take action to restrict or eliminate the interference." The publication of the proposed regulations, at least at first, did not cause much of a stir, primarily because most of them were a reflection either of existing federal subsistence rules (as they related to wildlife management) or of existing state fishing regulations. [57]

But despite Stevens' advice, and despite the federal government's issuance of proposed subsistence fisheries regulations, the Alaska legislative leadership made no attempt to formulate or present a subsistence bill that conformed with ANILCA's provisions. Instead, it took an opposite tack. On January 12, which was the first day of the 1998 session, the Alaska Legislative Council (ALC)—fourteen lawmakers, mostly Republicans, whose role was to act on the Legislature's behalf when the body was not in session—filed suit in the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C. This suit challenged the authority of the Department of the Interior to pre-empt state management of fish and game in Alaska. This suit, called Alaska Legislative Council vs. Babbitt, was similar to the Alaska vs. Babbitt case that the Knowles administration had dropped in early 1995; by filing its suit, the legislature (which had vociferously protested when the administration had abandoned the suit) signalled its intent to revive the arguments that the Hickel administration had originally propounded back in 1992. [58] The ALC was careful to file its suit in the District of Columbia District Court because previous filings regarding ANILCA and subsistence "have not fared ... well" in either the District Court in Alaska or the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. On January 23, Interior Department lawyers asked the D.C. District Court to move the case back to Alaska; that move was denied, however, and the case was eventually heard by D.C. District Court Judge James Robertson. [59]

Aside from the ALC lawsuit, Alaska's legislators made several moves in 1998 on subsistence-related issues. At first, prospects for an bill aimed at solving the subsistence dilemma seemed particularly bleak; on the session's first day, for example, House members Mark Hodgins (R-Kenai) and Vic Kohring (R-Wasilla) introduced a bill (HB 295) that would have prohibited state troopers from enforcing federal statutes or regulations on subsistence hunting and fishing in Alaska when those laws or regulations violate either the state or federal constitution. [60] Although the Knowles administration attempted to convince lawmakers to adopt the recommendations of the subsistence task force, the resolution containing those recommendations (HJR 46) was not seriously considered. [61] What did emerge from both the House and Senate was a subsistence bill (HB 406) stating that preference for subsistence resources would be limited to areas where a "cash-based economy" was not "a principal characteristic of the economy, culture, and way of life." [62] Inasmuch as many legislators were critical of ANILCA's rural provision, because it provided subsistence privileges to many rural residents that did not take part in a subsistence harvest while denying those privileges to non-rural residents who had a historical pattern of doing so, HB 406 (according to its sponsors) was an attempt to legalize subsistence opportunities for those who truly deserved it. Critics charged, however, that the bill's provisions were so restrictive that subsistence activities might be eliminated virtually everywhere. They also claimed that the bill disregarded community traditions; that it would be a bureaucratic nightmare; and—perhaps most important—that it would not prevent a federal takeover of the state's fisheries. [63]

The legislative session adjourned for the year on May 12. Well before that time, however, Knowles had made it known that he would veto the legislature's bill, primarily because it did not resolve the state's subsistence quagmire. [64] As an alternative, he called the legislature into a special session, which was to begin on May 26.

Just one day after legislators adjourned, a new group called Alaskans Together came into being. That group, headed by Anchorage businessman and sportfishing advocate Bob Penney, was formed with the sole purpose of allowing Alaskans a statewide vote on a subsistence bill. [65] Knowles, for his part, hoped that the legislature would adopt a resolution (HJR 101) that was based on the recommendations of his 1997 subsistence task force. (In an attempt to mollify legislators who chafed at ANILCA's perceived inequities, this bill would "allow" the Legislature to adopt a rural preference but did not "require" one.) On May 28, however, the resolution fell victim to a 20-20 tie vote in the House; given that vote, the Senate never voted on it. The special session sputtered to a close on June 1 without adopting any sort of subsistence bill. [66]

The indefatigable governor, still hoping for a solution, pressed state leaders for yet another vote on the issue. On July 3, he ordered the legislature back for a second special session, to begin on July 20. Legislative leaders—many of whom had been part of Knowles' task force—told the governor that they were frankly uncertain as to whether a bill could be passed that was compatible with ANILCA's provisions. House leaders, building upon efforts made in the previous special session, cobbled together one plan that made some effort among fellow legislators. But the last-ditch plan was unable to garner a broad base of approval; a House resolution (HJR 201) passed 22-17, five votes short of passage, and the Senate never took a vote. Just two days into the session, legislators voted to adjourn and return to their home districts. [67] Secretary Babbitt, in response, issued a press release expressing his disappointment at the legislature's inaction. The state's failure to act, he noted, "leaves the U.S. no choice but to oppose any extension of the moratorium on final subsistence fishery management rules" and that "the subsistence management requirements of federal law must now be implemented by federal agencies." The federal government, he noted, was fully prepared to begin managing the federal subsistence fisheries beginning December 1. [68]

|

| In 1998, Anchorage sport-fishing advocate Bob Penney expressed his frustration with the legislature's lack of progress on a subsistence amendment that he organized a group called Alaskans Together. His plan, however, was ignored in favor of Governor Knowles's plan, which fell victim to a tie vote in the Alaska House. ADN |

Just three days after they adjourned, lawmakers learned that a district court judge had dismissed the lawsuit (Alaska Legislative Council vs. Babbitt) that the ALC had filed in January. (The judge, James Robertson, had done so because the six-year window in which lawsuits could be filed against ANILCA had lapsed more than a decade earlier.) Legislators, taking a quick glance at the calendar, recognized that just two days remained to pass a bill, calling for a constitutional amendment, that could be voted upon by Alaskans in the November 1998 election. But inasmuch as there was no groundswell of interest for convening a third special session, the electoral deadline passed without incident. The ALC then requested that the case be heard in the District of Columbia appeals court. [69]

Throughout the 1998 state legislative season—the regular session plus the two special sessions—federal bureaucrats had been reluctantly preparing for what, all felt, would be a December 1, 1998 assumption of fisheries management on Alaska's federal lands. Beginning in late January, and extending through late March, the Office of Subsistence Management held 31 public hearings in locations throughout urban and rural Alaska on the proposed regulations that had been issued the previous December. These meetings had two purposes: to educate the public regarding the rationale behind the new regulations, and to receive comments on the relevance and appropriateness of specific proposed regulations. Interested persons were given 120 days—until April 20—to submit comments. In response to particulars in the proposed regulations, many Alaskans submitted oral comments at both public hearings and Regional Advisory Council meetings, and 74 written comments were also submitted. [70]

On August 11, 1998, Alaska Federation of Natives President Julie Kitka wrote to Secretary Babbitt, urging him "to oppose any congressional attempt to continue the current moratorium against implementing the Katie John ruling." Rep. Don Young as well as Sen. Frank Murkowski had, by this time, introduced legislation to extend the Congressional moratorium for another two years. But as late as September 10, Senator Stevens had been consistent in his public statements that he would not pursue an extension. [71] That resolve apparently changed, however, toward the end of September; he met with Secretary Babbitt and attempted to broker a third postponement: a ten-month moratorium ending on September 30, 1999. Babbitt agreed, but the Secretary did so only by convincing Stevens to agree to the following: 1) allowing final regulations relating to federal subsistence fisheries management to be printed, 2) offering $11 million for subsistence management purposes. (If the state legislature succeeded in placing a subsistence amendment on the ballot prior to September 30, the state received the allotment; if not, the funds would be directed to the Interior and Agriculture departments. If the state did not act by June 1—presumably at the end of its regular legislative session—$1 million of the $11 million allotment would be directed to federal agencies as an advance payment.)

|

| Robin Taylor, a legislative leader from Wrangell, has long opposed the passage of any subsistence bill that contained rural preference language. Alaska LAA |

The Stevens-Babbitt deal was announced on October 13. Babbitt noted that "I do this with some reluctance, because immediate protections would be appropriate. ... But, we must recognize the practical reality that the federal agencies involved need time and planning for orderly implementation of a federal program. This approach provides us that." Stevens, for his part, recognized that he was grateful for the reprieve; "The Secretary drove a hard bargain," he noted, and the remainder of the Alaska Congressional delegation was quick to agree to the deal. The AFN's Julie Kitka, predictably, was "angry and disappointed," but opponents of a rural preference such as Rod Arno (of the Alaska Outdoor Council) and Sen. Robin Taylor (R-Wrangell) were pleased by the action. Some were caught by surprise: ex-Attorney General Charlie Cole felt "duped" by the secret pact, and Interior Department representative Deborah Williams, who was apparently not informed of the negotiations, announced that she was resigning her position shortly after hearing that a deal had been consummated. [72] Language implementing the delay was included in the Omnibus Appropriations Bill that was then being finalized in Congress. [73]

On December 18, just two months after Babbitt brokered his deal with Senator Stevens, the Interior Secretary finalized the final set of regulations pertaining to federal subsistence fisheries management. These regulations were released to the public on January 4, 1999 and were published in the Federal Register four days later. Babbitt, in a press release, said that "These regulations provide the framework we are prepared to undertake this year if the Alaska Legislature fails to take necessary actions. The Department of the Interior is under court order to ensure that Alaska is in compliance with federal law, and with today's announcement we begin the final steps." Babbitt and other Interior Department officials, at the time, expressed optimism that the legislature could pass a bill calling for a constitutional amendment allowing for a rural subsistence priority; if such a bill were passed, the federal government would postpone its assumption of fisheries management until Alaskans had the opportunity to vote on the measure in the 2000 general election. If such a bill were not passed, however, the final regulations—now completed and published—underscored the federal government's resolve to assume management over the subsistence fisheries later that year. (Asked at a January 5 press conference whether any new extensions might take place, Babbitt emphatically responded "No. If the Legislature fails to act this year, we will take over management on October 1, 1999.") Despite the large volume of public response to the December 1997 proposed rule—much of which had come from the ten regional advisory councils—there were few substantial changes between the proposed and final regulations. Subsistence users, moreover, were assured that "Little change in existing subsistence fishing practices in rural areas is initially anticipated under these regulations, because they largely parallel existing state regulations." [74]

It was probably no coincidence that the federal government's final subsistence management regulations were released just prior to the convening of the 1999 session of the Alaska State Legislature, and starting on January 19—when the opening bell rang—legislators felt more pressure than ever to work out a bill that would allow the state to continue managing its subsistence resources. [75] The stark reality, however, was that chances for passage of such a bill were slim in the Senate and questionable in the House. Hoping to move some sort of bill, House Speaker Brian Porter (R-Anchorage) first floated the idea of a bill that would grant a hunting and fishing preference to subsistence users rather than to rural residents. A month later, however, Interior Department officials rejected the idea as being unworkable. In mid-April, Governor Knowles renewed his call for a subsistence solution and asked legislators to pass a bill that would allow Alaskans to vote on the measure. (Knowles, urging legislators to act, said that "if they fail to act on a constitutional amendment, they will be remembered as the Legislature that let in the Trojan horse of federal management.") Stevens, by this time, had told the legislature that it was "your decision, your judgment" because he had washed his hands of the matter, and Senator Murkowski had likewise stated that no more "takeover delays" would be forthcoming. [76] But the legislature showed no particular willingness to address the subsistence issue—one leading legislator noted that it would be a "waste of time" even holding hearings on the issue, considering its many past failures—and it adjourned on May 19 without having passed a significant subsistence bill. [77] Governor Knowles, hoping to avert the looming trainwreck, warned legislators that he would be calling them back into a special session on the topic in either August or September. House Majority Leader Joe Green, for his part, vowed that legislators would meet in a bipartisan "subsistence summit" in hopes of working out a broadly-applicable solution. [78] The summit, however, was never held; as Green later noted, too many legislators were "dug in" on one side or another to warrant such a meeting. [79] Meanwhile, the June 1 deadline (which had been worked at by Babbitt and Stevens the previous October) came and went, ensuring that the federal government received an initial $1 payment to begin preparing for the implementation and enforcement of federal subsistence regulations. [80]

|

| In June 1999, House Majority Leader Joe Green (R-Anchorage) attempted to organize a bipartisan "subsistence summit." But the positions of House members were so firmly entrenched that the idea was soon abandoned. Alaska LAA |

In mid-July 1999, less than three months before the October 1 deadline, the District of Columbia appeals court dealt the legislature another blow; it decided to reject the Alaska Legislative Council's appeal of the suit (Alaska Legislative Council vs. Babbitt), that the District Court had dismissed in July 1998, citing the ALC's lack of standing in the matter. [81] Then, on August 10, Governor Knowles announced that he would be calling the legislature back into session in late September. "We are facing a severe threat to our sovereignty," he intoned, "The day of reckoning is here." To give the legislature a head start on its deliberations, he offered specific wording for a proposed constitutional amendment. It read: "The Legislature may, consistent with the sustained yield principle, provide a priority to and among rural residents for the taking of fish and wildlife and other renewable natural resources for subsistence." Legislative leaders, however, were not optimistic; neither the Senate President nor the House Speaker were confident that they could muster up the necessary votes (14 and 27, respectively) to pass the constitutional amendment [ 82]

The special session began on September 22, and one of the state house's first acts was to introduce Knowles' proposed resolution as House Joint Resolution 201. But after a few days of mulling it over, legislators substituted their own resolution (HJR 202), which read

The legislature may provide a preference to and among residents for a reasonable opportunity to take an indigenous subsistence resource on the basis of customary and traditional use, direct dependence, proximity to the resource, or the available opportunity of alternative resources. [83] The preference may be granted only when the harvestable surplus of the resource, consistent with the sustained yield principle and sound resource management practices, is not sufficient to allow a reasonable opportunity for all beneficial uses. [84]

After a few additional days, the resolution—still numbered HJR 202—was reworked to read as follows:

The legislature may, consistent with the sustained yield principle, provide a preference to and among residents to take a wild renewable resource for subsistence uses on the basis of customary and traditional use, direct dependence, the availability of alternative resources, the place of residence, or proximity to the resource. When the harvestable surplus of the resource is not sufficient to provide for all beneficial uses, other beneficial uses shall be limited to protect subsistence uses. [85]

On Tuesday, September 28, House members voted on the resolution, which was controversial because it failed to specify a rural priority. [86] The resolution passed, 28-12. Action then moved on to the State Senate, where members had crafted a more narrowly-defined resolution (a Finance Committee Substitute for HJR 202) calling for a rural preference. In a key vote, held on the morning of Wednesday, September 29, senators voted 12-8 in favor of the proposal. But because the proposed constitutional amendment required a two-thirds vote for passage, the resolution fell two votes short. [87] In a brief Thursday meeting, the Senate chose not to reconsider the vote it had taken the day before, and the decision was made to adjourn. [88] Federal subsistence managers, for better or worse, were in the fisheries business.

D. Federal Planning Prior to Fisheries Assumption

On October 1, 1999, federal subsistence officials released a series of press releases that announced the obvious: the commencement of federal subsistence management of fisheries on the navigable waterways in, or adjacent to, Alaska's federal conservation units, and the transfer of an additional $10 million to the Interior and Agriculture departments (agreed to by Stevens and Babbitt as part of the October 1998 moratorium) to fund a federal subsistence management program. Officials were quick to state that they were undertaking such an action with considerable reluctance. They announced that regulations under the new regime would largely resemble those that were already in place; that many of the state's most popular commercial and sport fisheries would be largely unaffected by the change; and that to the largest extent possible, they would rely on state personnel and state-generated data in order to effectively fulfill their management mandate. Statements issued by federal as well as state fisheries officials made it plain that a single, state-managed fisheries management system was preferable to the newly-established dual management system. But the appeals court decision in the Katie John case, combined with the legislature's failure to forward a constitutional amendment to Alaska's voters, left federal officials with no other alternative. [89]

Given the terms of the October 1998 moratorium, and the strong subsequent statements made by both Senator Stevens and Secretary Babbitt, it surprised virtually no one that the legislature's failure to act in 1999 was followed by the federal assumption of fisheries management. Given that climate throughout the year, federal officials effectively had a year to prepare for fisheries management. But inasmuch as there had been three previous moratoria, two of which had been worked out at virtually the last minute, the federal government by October 1999 was fairly well versed in the politics of brinkmanship; more important, it (by necessity) had a strong track record in planning for a possible fisheries assumption.

As noted above, Senator Stevens and Secretary Babbitt had cobbled together the first fisheries moratorium in March 1996. Even before that time, officials on the Federal Subsistence Board's staff committee had informally begun to plan for the day—which was unspecified at that time—when the federal government might begin managing the state's subsistence fisheries. But federal officials made few concrete plans during this period. In September 1997, when the second moratorium was worked out on the fiscal year's last day, the extent of the federal government's preparedness was the completion of a draft question-and-answer sheet; beyond that, federal officials were hopeful that a Proposed Rule on subsistence fisheries would be readied "shortly after October 1." It was similarly felt that a Final Rule would be completed "likely during the Spring of 1998" and thus in time for the 1998 fisheries season. [90]

Federal officials, still hoping for a legislative resolution, made no specific preparations for a fisheries assumption during the first half of 1998 except for the extensive public process (noted above) related to the Proposed Rule that had been issued in December 1997. Governor Knowles focused his efforts that year on a special session, and both he and federal officials were hopeful that that session would break the subsistence impasse. But the special session adjourned on July 21 without forwarding a proposed constitutional amendment to Alaska's voters. In response to the legislature's inaction, Secretary Babbitt issued a press release announcing that he and Agriculture Secretary Dan Glickman fully intended to assume management over the state's federally-managed subsistence fisheries when the current moratorium expired on December 1. And to prepare for that eventuality, the two secretaries had written to both the Office of Management and Budget and to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees requesting $9.5 million to implement the court order in the Katie John case. [91] Regarding specific planning actions, the Secretary noted that:

In proceeding with implementation, final regulations can not be published before December 1, 1998. A timeline is currently under development that outlines the steps leading to the publication of these regulations. ... The new federal subsistence fishing regulations are planned to go into effect with the spring 1999 seasons. Detailed operational planning, and discussions on coordination with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game are now being initiated, in preparation for the implementation. [92]

The National Park Service, along with the other agencies represented on the Federal Subsistence Board, was already well underway in its planning efforts by this time; they had been goaded into action in April 1998 by the Secretaries' budget request. At that time, federal authorities had concluded that the NPS would receive $1.85 million out of the projected $9.5 million fiscal year 1999 budget allotted to subsistence fisheries management, [93] and agencies officials had already compiled a fairly specific budget outlining how its allotment would be spent. The agency, in its attempt to formulate a decentralized fisheries management system, proposed four park clusters; within each cluster, it proposed a budget including labor needs and ancillary expenses. [94]

Because federal officials had commenced a stepped-up effort in July 1998, they were better prepared than ever for a possible fisheries assumption when Senator Stevens and Secretary Babbitt worked out a third fisheries moratorium that October. Their agreement, moreover, paved the way for the issuance of final subsistence fisheries regulations; as noted above, they were issued in early January 1999, almost nine months before the moratorium expired. Given the tone of both Stevens's and Babbitt's verbiage in the months that followed their October 1998 pact, federal officials had a greater-than-ever certainty that a fisheries assumption would indeed take place if the state legislature failed to act. As a practical matter, therefore, officials had almost a year to map out the details relating to a federal subsistence fisheries program.

Federal officials, in fact, made the most of the months that remained before October 1. Their first task was writing an overview of how the federal subsistence fisheries program would be organized and implemented. On March 26, the Federal Subsistence Board's staff committee sketched out a brief Fisheries Implementation Work Plan. That plan, released in tabular form, delineated fourteen specific issues; [95] within each issue, it outlined a series of steps within each issue that had to be addressed by specific deadline dates. By April 21, the work plan had evolved into the Federal Subsistence Fisheries Implementation Plan, which called for the creation of a series of subcommittees or working groups related to each of fourteen issues and the publication of a series of issue papers. [96]

The Staff Committee, as promised, set to work on completing issue papers related to all fourteen issues, and by June 14 brief "issue papers"—in reality nothing more than a list of goals, tasks and assignments—had been completed on all fourteen topics. [97] Two of these topics, however, demanded a more detailed treatment: 1) organizational structure, staffing, and budget, and 2) information needs (data management). In order to work on these topics, the Federal Subsistence Board began by establishing a six-person subcommittee on information needs and information, which was called the Organizational Blueprint Sub-Committee. Patty Rost, Gates of the Arctic's Resource Management Specialist, was its NPS representative. The group immediately went to work. By July 9, each of the federal government's four major land management agencies had submitted reports detailing information issues and concerns; the subcommittee, in turn, used that information to compile a document called Federal Subsistence Fisheries Management: Operational Strategy for Information Management, which was presented to the Federal Subsistence Board on August 2. [98]

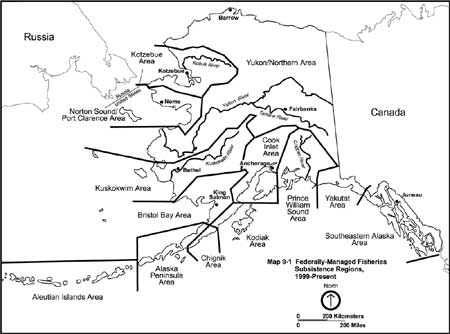

| Federal Fisheries Region |

State Fisheries Region |

Arctic/Kotzebue/Norton Sound |

Kotzebue-Northern, Norton Sound-Port Clarence |

Yukon River | Yukon |

Kuskokwim River | Kuskokwim |

Bristol Bay/Alaska Peninsula/Kodiak | Aleutian Islands, Alaska Peninsula, Chignik, Bristol Bay, Kodiak |

Cook Inlet/Gulf of Alaska | Cook Inlet, Prince William Sound |

Southeast Alaska | Yakutat, Southeastern Alaska |

The report introduced several concepts that have been followed by federal fisheries managers ever since. One major decision that the subcommittee made was to organize Alaska, for the purpose of subsistence fisheries information gathering, into six regions. [99] It was widely recognized that the ten-region structure that the Federal Subsistence Board had established for wildlife management in April 1992 could not logically be applied to the state's fisheries; and the subcommittee likewise agreed that federal fisheries managers—for the purposes of information gathering—did not need to use the same thirteen-region system that the Alaska Department of Fish and Game had long used. The six recommended regions, it should be noted, would be for information gathering only. Inasmuch as the January 1999 Final Rule delineated the subsistence fisheries according to state fisheries areas, the federal government decided to continue to use thirteen state-defined fisheries areas for regulatory purposes. For federal advisory purposes, however, the existing ten-region system held sway. The August 1999 report made no attempt to recommend a separate regional advisory structure for fisheries management. Fisheries management proposals, therefore, would continue to be discussed and evaluated by the same ten regional advisory councils that had been in existence since the fall of 1993.

Beyond those geographical parameters, the report detailed the process by which information input and management decisions would interplay before, during, and after each fisheries season. In addition, it identified three classes of information needs—subsistence harvest studies, stock status and trends studies, and traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) studies [100]and it outlined a process by which federal officials would generate and evaluate fisheries research projects within these three classifications. The report, which received a broad approval from federal board members, served as the basis for sequential efforts.

Table 9-1. Proposed Staff and Budget for Federal Subsistence Fishers Management, Summer 1999

| Program Administration: | Proposed New Staff | Proposed Budget | ||

| Agency | FY 2000 | FY 2001 | FY 2000 | FY 2001 |

| Office of Subsistence Management | 7 | 14 | $2,000,000 | $2,345,000 |

| National Park Service | 9.5 | 16 | 1,000,000 | 1,805,000 |

| U.S. Forest Service | 7.5 | 15 | 967,000 | 1,580,000 |

| Fish and Wildlife Service | 3 | 6 | 969,000 | 1,221,000 |

| Bureau of Indian Affairs | 1 | 2 | 130,000 | 245,000 |

| Bureau of Land Management | 1 | 2 | 140,000 | 200,000 |

| DOI Office of the Solicitor | 1 | 1 | 115,000 | 115,000 |

| 30 | 56 | $5,321,000 | $7,511,000 | |

| Resource Monitoring: | Proposed New Staff | Proposed Budget | ||||

| Agency | FY 2000 | FY 2001 | FY 2005 | FY 2000 | FY 2001 | FY 2005 |

| National Park Service | 10.6 | 12.0 | 16.8 | $1,089,000 | $$1,858,000 | $$2,601,000 |

| U.S. Forest Service | 22.0 | 21.0 | 29.4 | $2,033,000 | $3,920,000 | $5,706,000 |

| Fish and Wildlife Service | 22.4 | 28.0 | 39.2 | $2,283,000 | $4,958,000 | $6,773,000 |

| Bureau of Indian Affairs | -- | -- | -- | $130,000 | $255,000 | $357,000 |

| Bureau of Land Management | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.8 | $144,000 | $400,000 | $560,000 |

| 56.6 | 63.0 | 88.2 | $$5,679,000 | $$11,391,000 | $$15,997,800 | |