|

National Park Service

MISSION 66 VISITOR CENTERS The History of a Building Type |

|

CHAPTER 1

Quarry Visitor Center

Dinosaur National Monument, Jensen, Utah

Surrounded by the dry, rocky terrain of northwest Colorado and northeast Utah, over two hundred miles from any major city, Dinosaur National Monument is an unlikely location for one of the Park Service's most distinctive modernist buildings. Even before its completion in 1958, the "ultra-modern" Quarry Visitor Center at Dinosaur had become a model of Mission 66 design and achievement. Its glass and steel observation deck, concrete ramp, and cylindrical "tower" suggested scientific inquiry and sheltered working paleontologists.

The transformation of the monument from a paleontological site to a visitor destination worthy of such attention resulted, in part, from one of the country's bitterest conservation battles. The canyon near the confluence of the Green and Yampa Rivers was the preferred location for a Bureau of Reclamation dam, and had been eyed by the Bureau for inclusion in the Upper Colorado River Basin Project since the 1930s. Legislation passed to expand the monument in 1938 included provisions for future development of water resources. What appeared to be a matter of local water rights in the late 1930s, however, would become a topic of national discussion after World War II. If the value of Dinosaur National Monument lay in its paleontological site—the richest deposit of Jurassic remains ever discovered—its sudden notoriety came from the high canyon walls and rushing rivers that the river development project promised to transform into power, irrigation, and drinking water. The dam controversy touched the heart of the National Park Service by threatening its basic mandate to protect individual parks and the integrity of the entire system. It pitted governmental departments against each other. Even within the Park Service, staff members stood on either side of the issue. The public was equally divided. This was an era in which big water projects such as Hoover Dam were wonders of engineering constructed for public benefit. The importance of preserving scenic beauty didn't make sense to many state residents, who saw the monument as a barren wasteland, or to Mormons, who believed that creating an oasis in the desert was their mission and God's will. At the same time, as many Westerners demanded equal water rights, members of the growing national "wilderness movement" saw the Echo Park Dam development issue as an opportunity to prevent a loss equivalent to that of Yosemite's Hetch-Hetchy Valley. [1]

The Echo Park and Split Mountain Dams appeared a foregone conclusion to many by 1950, when newly appointed Secretary of the Interior Oscar Chapman scheduled hearings to discuss the proposals. Among the monument's supporters was Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., the nation's foremost landscape architect, who warned that the loss of "scenic and inspirational values obtainable by the public" at the monument would be "catastrophically great." [2] Olmsted urged the Department of the Interior to choose an alternative site, even if it resulted in financial loss. Despite such pleas, Chapman supported the dam. The headline of the January 28 Salt Lake City Tribune read "Echo Park Dam Gets Approval." Less than a year later, the Park Service announced plans for a resort-like development at the new Echo Park and produced a sketch of Echo Park Lodge, a vast complex for 500 visitors estimated to cost $2,500,000. Park Service maps indicated the areas that would be flooded and showed the locations of both Split Mountain and Echo Park Dams and reservoirs. [3]

The Park Service may have given up the fight after the Secretary of the Interior's decision, but grassroots conservation groups refused to back down. Media attention had been building since the hearings, and in July 1950, an article by Bernard DeVoto informed over four million Harper's readers of a potential tragedy at Echo Park. Rather than appeal to a public sense of environmental responsibility, DeVoto addressed the question of public ownership.

No one has asked the American people whether or not they want their sovereign rights, and those of their descendants, in their own publicly reserved beauty spots wiped out. Thirty-two million of them visited the National Parks in 1949. More will visit them this year. The attendance will keep on increasing as long as they are worth visiting, but a good many of them will not be worth visiting if engineers are let loose on them. [4]

DeVoto, a native of Utah, helped make the situation a popular issue, and once it reached a national forum new coalitions joined the conservationists. Californians protested that their water was being diverted, while Easterners declared themselves unwilling to pay taxes for western water projects. The campaign to save the canyon was given an additional boost in 1952, when David Brower became president of the Sierra Club. After seeing a film of the river, Brower made the preservation of Dinosaur his personal crusade. The new Sierra Club leader encouraged others to take up the fight by sponsoring river trips, producing his own film, and writing and speaking on behalf of the monument. Brower asked New York publisher Alfred A. Knopf to publish This is Dinosaur, a collection of essays by notable wilderness advocates intended to show "what the people would be giving up" if they accepted the dams. [5] Each member of Congress was sent a copy of the book, with a special brochure about the monument sewn into the binding. That Dinosaur was suddenly in the national spotlight is perhaps best illustrated by the 1954 movie, The Long, Long Trailer, starring Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz; "Daisy" overloads the newlyweds' double-wide trailer with her favorite souvenir, a very large rock from Dinosaur National Monument.

Finally, in November 1955, Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay announced that Echo Park would be removed from the Upper Colorado River project. [6] In March, both Houses approved water storage at three sites—nearby Flaming Gorge, Utah; Glen Canyon in Northern Arizona; and Navajo, New Mexico; the inclusion of Curecanti, Colorado, was contingent on further research. The threat of future development at Dinosaur remained, but for the present, the monument would be left alone. The Park Service quickly took advantage of this lull in the controversy to push for the long-awaited in situ visitor center at the now nationally famous site. Mission 66 came to Dinosaur amid this clash of ideals. In part because of the water project publicity, the Park Service chose to construct a monumental modernist building that demonstrated its commitment to the "protection and use" of Dinosaur National Monument. [7]

A Shelter for the Quarry

In 1909 Earl Douglass discovered an amazing deposit of fossilized dinosaur bones in the remote and arid northeastern corner of Utah. Douglass, a paleontologist from the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, established a camp at the site from which to begin excavating the valuable remains. Over the next few decades entire skeletons were removed and sent to museums throughout the country—approximately 700,000 pounds of fossilized bones to the Carnegie alone. These prodigious discoveries led President Woodrow Wilson to proclaim Dinosaur a national monument in 1915. About this time, Douglass envisioned a museum exhibit with "the skeletons which had been unearthed . . . mounted in relief on one side of the paleontological hall of the museum in the position in which they had been found." [8] A few years later, he preferred "a stately edifice in which there should be assembled plaster-casts of the dinosaurs which we have extracted from the spot." [9] Finally, in 1924, Douglass wrote what might easily have been preliminary instructions for the architects of Quarry Visitor Center:

The uncovered area should be housed to protect the specimens and provide shelter for sight-seers and students. The north side would be a natural wall, of course, with the skeletons in place. The south side would probably be a natural wall also but the ends would have to be built and a roof with ample sky lights would cover the whole. The extra space and the walls could be utilized for many other exhibits from this most interesting geological and paleontological region. [10]

If Douglass was the driving force behind the visitor center concept, public servants in higher places had more influence over construction within the monument. George Otis Smith, Director of the U. S. Geological Survey, expressed his preference for an in situ exhibit as early as 1916, and by 1923 Secretary of the Interior Herbert Work imagined a similar situation and encouraged the Smithsonian to take on the project. Evidently, local residents believed that a building at the Quarry was eminent. The board of the Vernal Chamber of Commerce estimated that a shelter featuring a roof with three skylights and end walls of native rock would cost about $5,000. Although Work was unable to obtain approval for his scheme, he did attract the attention of Director Cammerer and members of the scientific community. Cammerer expressed concern over the amount of labor necessary to reveal exhibit bones and feared incurring additional expenses. Nevertheless, in 1924, Congressman Colton of Vernal introduced Bill 9064 to the 68th Congress in an effort "to properly house for its protection the Dinosaur National Monument." [11] Congress shelved the bill, but Colton continued to fight for a protective shelter.

Meanwhile, Cammerer focused on finding an academic institution to resume excavations in partnership with the park. Dr. Case of the University of Michigan Geology Museum, a group active in excavating the site, hesitated to reveal fossils that might deteriorate when exposed to the elements. Financial support was a problem for the university as well, and in 1925 Cammerer decided to halt excavation until something could be done to protect the bones. Finally, in 1930, the American Museum of Natural History in New York bargained with the Park Service for rights to fossilized remains in exchange for developing a public exhibit. Museum excavators would be allowed to remove any full skeletons they unearthed. The Depression ended hopes of building a museum in the early 1930s. However, a federal relief project resuscitated the excavation efforts in 1933, promising twenty workers. Even after the removal of funding in the spring of the next year, work continued under the Transient Relief Service of Utah. A temporary structure for the paleontologists, which also served as a museum, was constructed on the site in 1936. [12]

The relief work primarily involved "overburden removal," but as this task was accomplished the Park Service began planning for a new museum. Ned J. Burns, chief of the museum division, warned that "the building must be erected as soon as possible after this work has advanced to a stage where the fossils are located and enough exposed for identification." Not only did Burns anticipate potentially damaging water seepage, but also several features of the building. He thought the structure housing the in situ exhibit should be "entirely functional with ornamental treatment reduced to a minimum." The balcony opposite the rock face would allow visitors to observe excavation. In closing, Burns noted that "an in situ exhibit of the size contemplated will . . . achieve international fame," but warned the Park Service to obtain the necessary funds before beginning construction. [13]

Burns may have been referring to a preliminary design for a museum produced in January 1937, and, remarkably, the early proposal most similar to the Quarry Visitor Center. The project assumed collaboration with the American Museum of Natural History, the chief architect of WODC, and the director of the Park Service. Unlike successive designs of the 1940s, this scheme contains a circular foyer, apparently of concrete, which acts as a hinge linking the Quarry exhibit area with an optional office wing. The narrow museum building includes a library and curatorial office on the first floor, and stairs adjacent the foyer and at the far end of the museum lead up to a second-floor balcony space, enabling visitors to circulate without backtracking. In elevation, the building is simple and streamlined, with only a random stone facade as ornamentation. Its strip clerestory windows, flat roofs, and use of geometric forms is more characteristic of Mission 66 than the rustic architecture typical of the Park Service in the 1930s. [14]

Interest in the Quarry area appears to have increased in 1938, probably because the enlargement of the monument from eighty acres to three hundred and twenty-five square miles brought attention and financial support to the area. [15] Signs were installed on Route 40. In his inspection of the monument, Assistant Chief of the Naturalist Division H. E. Rothrock reported on the prospect of further excavation in the quarry: "This work cannot be undertaken until the plans and the exact location of the building which is to house the exhibit have been completed. These plans await the excavation of the fossil bed because the location of the building and its general design will depend upon the location, condition, and abundance of the fossil material which exists in the bone layer." [16] If funding for the building had been an obstacle in the past, it must have seemed impossible during World War II. Nevertheless, in April 1944, the Park Service produced two alternatives for museums in the Quarry area.

The preliminary sketch for a museum, designated 3-B as if in relation to the 1937 proposal, shows a more elaborate facility with a less modern appearance. The main exhibit room is a 60- by 160-foot rectangle composed of an in situ exhibit on the north side and exhibit cases or dioramas on the south underneath a second-story viewing balcony. Visitors traversed a winding path up the rock (and adjacent the road) to reach the main entrance to the building, entered a lobby with restrooms, viewed the quarry face, walked downstairs to the exhibit room, and then exited through a vaulted loggia on the first floor which also served as a truck entrance. The laboratory and preparation room was located in a one-story side wing jutting out from the front of the building, and additional offices were on the second floor of part of this wing. The building had a random stone facade and terraces but no significant ornament. [17]

A third museum proposal (drawing 3-C) wedged the building between the in situ quarry and the southern canyon wall, with a slightly undulating stairway providing access to the exhibit room, a second-floor mezzanine, and third-floor balcony. Offices were on the south side of the building and on the second floor. An optional skylight was included in the section, along with triple-height side windows. The general plan of the building qualifies it as an ancestor of the future Quarry Visitor Center, as does the basic circulation pattern. A quick glance at the elevation ends the comparison, however, as it is a massive three-tiered structure with vaguely Spanish details. One feature of note is the boulder-lined path that follows the entrance road up to the second-floor roof terrace.

Fortunately, the Park Service's financial situation did not lend itself to such an elaborate Quarry complex. [18] A temporary shelter was more realistic, and by 1951 plans were approved for a utilitarian structure resembling a warehouse or farm building. The north wall of the building consisted of the quarry face itself and a corrugated sheet metal shed roof protected paleontologists and visitors alike. Four equally spaced windows in the south wall above the entrance and one on the east side let light into the museum. The lowest construction bid was offered by Bus Hatch, a native Vernal "river man" who had guided boatloads of tourists through the canyons during the preservation effort. [19] Although a rather primitive wooden structure, this early museum was a precedent in situ shelter serving the required protective function. The new Quarry Visitor Center would not only borrow its method of bringing the site to the visitor, but also its utilitarian quality updated to showcase modern materials and modern scientific efforts. Whether or not the contract architects examined the temporary shelter is unknown, but Park Service designers were certainly influenced by the building.

Mission 66 brought new hope of fulfilling promises for the Quarry area development envisioned twenty years earlier. Park staff met with members of the regional office and the WODC for three days in May 1955 to discuss upcoming construction projects. The group agreed to push for immediate preparation of preliminary drawings for the "Quarry Museum" and construction as soon as funds were available. Among those attending the meeting were Lyle E. Bennett and Robert G. Hall, both of whom probably contributed their design expertise to the committee's building description.

The building is to be designed with a length of approximately 180 feet, covering a general area of the quarry as located on the ground. The building is to have a balcony on the south wall at a height which will give the visitor the best possible view of the quarry face and the in situ exhibit. Entrance and normal visitor exit of the building would be at the balcony level near the center of the south wall. The circulation pattern within the building is to provide for visitors traveling from the balcony to the ground floor for a closer view of the in situ exhibit and other related exhibits planned for installation under the balcony and elsewhere in the building. [20]

By March 1956, the Park Service announced that funds allocated for Mission 66 improvements at Dinosaur totaled $615,899. [21] According to Director Wirth, the money would be used for roads, a new $275,000 visitor center, employee housing, and water and sewer facilities. [22] In May, just a month before hiring contract architects, the park produced a "comment sketch" for a modern visitor center. [23]This drawing shows a two-story building with an upstairs lobby and spectator's balcony. The lower floor housed offices and work rooms arranged en suite and a visitor gallery, probably intended for exhibits. Visitor access to the building was from a broad stairway running parallel to the offices. No comments or elevations were included in the sketch. At this point, the park must have been seeking a private architectural firm for help in designing the building. By mid-summer, work had begun on a guard rail at Harpers Corner, parking lots, and concrete channel crossings. Bidding began on water and sewage improvements and grading the residential housing in the quarry area. [24] Over the winter, Park Naturalist John Good envisioned the improved situation at the site, which would allow visitors to "whisk up a paved road to the quarry instead of walking up the hot, dusty trail that has been used for so many years." [25] If a paved road seemed such a luxury, Good could hardly have imagined the imminent transformation of the quarry from a temporary camp into a modern laboratory and visitor center.

In preparation for the new building, the Park Service removed facilities constructed during the 1930s. The museum section of the old headquarters was "cut from the naturalist's quarters portion and skidded across a narrow bridge and placed at its new location about a mile from its original site," an achievement "deemed impossible." [26] The park went to great lengths to replicate the quarry exhibit by installing a temporary contact station at Neilson Draw and building a trail up to in situ interpretation at Dinosaur Ledge. Fossilized backbones and large leg bones were exposed in the ledge area, and a ranger naturalist stationed at the site simulated excavation. [27] Throughout the construction, park personnel and local boosters described every step of progress in anticipation of a visitor center "distinctly different in design from anything at present constructed in other national parks." Park interpreters were optimistic that the new facility would finally provide an appropriate setting for modern paleontological research. For the next several years, visitors would witness actual excavation by professional paleontologists. This demonstration would be supplemented by a series of "exhibits, explaining what dinosaurs are, the world they lived in, the geological events following their death, discovery and working the quarry, and methods of preparing specimens." The visitor center would include laboratory facilities, such as a "preparation room for work on the bones, a technical library, storage space for study of collections, and a fully equipped darkroom." [28]

Anshen and Allen, Architects

Already the authors of a most stimulating and satisfactory building in one of our National Monuments (Chapel of the Holy Cross, Sedona, Arizona, Architectural Record, October 1956), architects Anshen and Allen have now designed an arresting and appropriate visitor center to house an "in-place" exhibit of America's largest deposit of dinosaur fossils. [29]

—Architectural Record, January 1957

The year Echo Park was saved, the San Francisco architectural firm of Anshen and Allen designed its most famous building, a small chapel in the Sedona desert. S. Robert Anshen and William Stephen Allen began private practice together in San Francisco about four years after their graduation from college in 1936. [30] Former classmates at the University of Pennsylvania, Anshen and Allen worked as a team, sharing the responsibilities of design and engineering. From the beginning, Anshen and Allen espoused no particular style or architectural methodology, but prided themselves on creating the "variety" that evolved naturally out of clients' desires and programmatic requirements. One of the partners' notable early buildings was a house designed in Taxco, Mexico, for Sonya Silverstone (1949). An article describing the residence inspired Marguerite Brunswig Staude to contact Anshen and Allen about the possibility of building her dream chapel in Sedona, Arizona. [31] The architects must have been intrigued when Staude, a sculptress, showed them her sketches of a Roman Catholic Church inspired by Rockefeller Center, a version of which was almost constructed for Hungarian nuns on Mount Ghelert in Budapest. Anshen and Allen began working on the chapel project in 1953. [32] Staude not only financed the chapel, but also provided accommodations for the architects at her Doodlebug Ranch in Sedona. When it was time to find an appropriate site, Staude, her husband, and the architects flew over the local hills in search of the perfect location. This type of collaboration between architect and client would also occur in the firm's work for the National Park Service.

The Chapel of the Holy Cross, a concrete and glass structure designed around a colossal cross, was built into dramatic red rock formations overlooking the town of Sedona. A serpentine concrete ramp leads the visitor out of the parking area and up to a courtyard in front of the chapel. Through the paned-glass entrance facade, the view extends to the concrete cross spanning the building's opposite wall and to clouds outside that seem to float above the altar. Anshen and Allen's chapel received praise in architectural journals, popular magazines, and newspapers soon after its construction. [33] Park Service architects must have known about this unusual structure located a short distance from Montezuma Castle National Monument and the monuments near Flagstaff—Sunset Crater, Wupatki, and Walnut Canyon. The chapel's textured concrete walls and sinuous ramp would foreshadow a similar use of concrete at Quarry Visitor Center. The glass wall that so successfully brought the outdoors into the building would be adapted to the conditions of the park site. Perhaps most important, the designs of both buildings would accommodate living rock. In its unadulterated simplicity, the chapel makes the most of modernist design, and Park Service architects might very well have hoped to see its secular equivalent in a national park. Architectural Record clearly saw the connection between the chapel's setting and the design challenges inherent in a park environment. The journal concluded its October 1956 story on the chapel with the following prediction:

It may fall to the lot of other architects to work with sites of similar grandeur, if plans for the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service do lead, as planned, to a substantial building program in the national parks. NPS and its concessioners in the parks will be dangling before architects just such problems in scale, in awesome scenery, color, lighting conditions. In an earlier day rusticity was the accepted answer, or chalet importations from another mountainous land. Contemporary architecture has not had much opportunity to test its tenets in such terrain, or, too much success when it has had the chance. The design of this chapel seems to suggest a better approach than we are used to in our national parks. [34]

Regardless of the Park Service's admiration for the Sedona chapel, initial contact between architects and client appears to have occurred as a result of the Mission 66 effort to find suitable contract architects for visitor center commissions. The WODC advertised its need for architects and, about six months after Anshen and Allen interviewed at the San Francisco office, the firm was hired to design Quarry Visitor Center. The partners chose Richard Hein as project architect. [35] From the beginning, a certain amount of collaboration was implied, but Anshen and Allen welcomed the challenge offered by their unusual client. In accepting the project, the firm was taking on decades of in-house planning, not to mention the responsibility of an early high-profile Mission 66 project. Anshen and Allen soon realized that the Park Service's expectations for its new building were influenced by the traditional park museum model; preliminary Park Service designs depicted a fully enclosed, windowless building lit exclusively by artificial light. When Anshen visited the site, he recognized the importance of opening up the building so that people could see the environment surrounding the covered quarry section. Together, Hein, Anshen, and Allen begin to plan an exhibit shelter

as open as possible in order to achieve a maximum integrated relationship of the remains to the site. The shelter was conceived as a totally glazed structure. This conception had the additional advantage of creating the least intrusion of the building on its natural surroundings which had been one of the Park Service's principal requirements. The administrative and utility areas were to receive a subordinate location and treatment to the main Exhibit Shelter in order to detract as little as possible from the public's view from the site. [36]

Technical aspects of the design were addressed by Robert D. Dewell, a civil and structural engineer based in San Francisco.

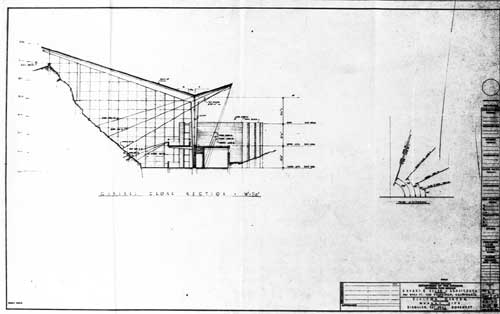

According to project architect Hein, the original concept for the visitor center made use of the site's natural landscape features by spanning the "v-shaped cut" in rock formations with "a series of suspension cables on a catenary curve." [37] Because the region's severe climatic conditions fluctuated up to 150 degrees throughout the year, the architects were forced to abandon this plan. The new scheme evolved from the original idea, but supported the asymmetrical butterfly roof with a more substantial rigid frame system. This solution solved the basic requirement of covering the quarry face, but departed radically from the Park Service's shed-like design.

Quarry Visitor Center was an original design by Anshen and Allen but it was also a collaborative effort with the National Park Service. In an oral history interview over twenty years later, Cecil Doty not only took credit for the original design, but remembered details of the collaboration process. With drawings to illustrate his points, Doty showed how he revised the building plans "on the basis of my second preliminary [drawing]" after Ronnie Lee pressured him to remove all glass from the exhibit gallery and make provisions for artificial lighting. Doty claimed that Anshen and Allen restored the glass, borrowed his shell and truss design, and then "went high tailing to Washington" and got approval for the building. As this controversy illustrates, work between private and Park Service architects often blurred the lines between client and architect. [38] In a feature article on "Recent Work of Anshen & Allen," Architectural Record described the building in glowing terms as a highly successful revision of "the Park Service's original design." [39]

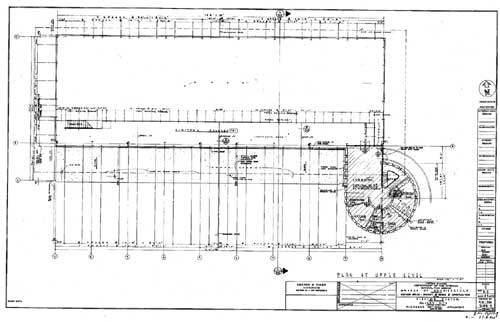

The firm produced a seven-sheet set of preliminary drawings in July 1956. Because of the large amount of glass in the plans, preliminary drawings included diagrams indicating the angle of the sun at various months and hours. "Sun patterns" were shown in plan and cross section. These solar studies were directly related to building features, such as the shape and extent of roof overhangs. The building consisted of three main areas: the concrete cylinder or "circular element" housing facilities for visitors, including the lobby, restrooms, and service staff; the one-story administrative office and laboratory wing; and the double-height gallery, which included the fossil exhibit. From the parking lot, visitors entered by following the concrete ramp as it wrapped around the cylindrical building and emerged adjacent the entrance to the exhibit area. The two floors were connected by a narrow stairway in the rotunda and by a stairway at the far end of the gallery; visitors were intended to use the ramp entrance, discover the restrooms to the left of a small lobby, walk along the upper gallery and then take the stairs down to the lower viewing area. This gallery included a window into the paleontologists' preparation and storage room, part of the administration wing. The first floor also housed the library and conference room, geologist's office, darkroom, employee lockers, and mechanical equipment. Visitors concluded their tour of the lower gallery at another lobby space, now a crowded bookstore. Additional Park Service offices were arranged in the semicircle around the lobby. The exit was located at the far end of the exhibit space. This route provided efficient circulation through the building and back to the parking area.

Evidently, Director Wirth was not entirely pleased with the preliminary drawings and, in July, refused their approval. Anshen responded by offering to "restudy the problem in accordance" with Wirth's comments. [40] The acting chief of design and construction reported his extreme doubts that a building satisfying the desired functional requirements could be designed and built with the available funds. As the architects worked on revisions over the next few months, they also demonstrated that their glass and steel building could be completed within the alloted budget.

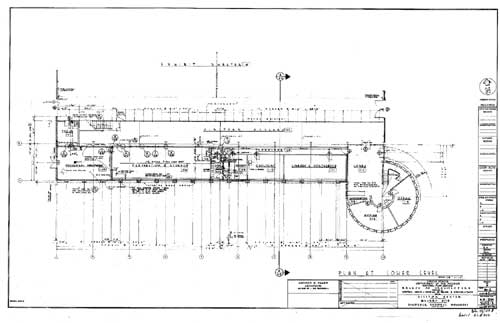

Figure 12. A cross section of Quarry Visitor Center showing the position of the sun at various times during the day. This was part of a seven-sheet set of preliminary drawings completed in July 1956. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The form of the gallery covering the fossils appears to have been determined relatively early in the design process, but the cylindrical administrative building proved more contentious. The architects produced at least ten versions of the ramp and cylinder, with variations in the treatment of "skin" covering the two-story office space, the size and shape of the ramp and its termination. These are all drawn in soft pencil, with a similar background treatment, as if part of a series. [41] The most significant variations occur in the concrete pattern of the cylinder; the architects varied the spacing of verticals, in one case leaving half the wall completely smooth and in another proposing a textured wall of concrete block. Ramp possibilities ranged in the extent of curve—including an example that seems almost level. The architects experimented with the ramp entrance and toyed with the idea of a series of steps part-way up the ramp. As Stephen Bruneel, senior associate of Anshen and Allen, speculated in 1999, the drawings suggest that "the final round form of the admin/service wing was arrived at early on, but that there was uncertainty or resistance either within the firm or with the client. The result causing a long detour before the original scheme was returned to." [42] This "resistance" was most likely directed at the building's function, rather than its modernist aesthetic, and resulted primarily from the museum department's desire for traditional, enclosed exhibits.

Ronald Lee's Division of Interpretation preferred the use of artificial lighting in the visitor center, and his influence was a determining factor in early in-house conceptions of the building. An enclosed, darkened exhibition space would allow museum technicians to employ dramatic lighting affects without any external distractions, create a sense of mystery, and propel visitors back to the time of the dinosaurs. However tempting such a performance might have been for the museum division, this traditional approach to exhibition defeated the purpose of a site specific exhibit. Visitors could not see the relationship between the enclosed part of the quarry and the continuing rock face outside. As Hein subsequently explained, "the Park Service design, while being suited to the normal concepts of museum planning, was failing to recognize the unique aspects of this particular project." [43] By August 1956, when Anshen and Allen had already submitted the first sketches of their glass-walled building, members of the museum and park staff had not only changed their minds about the display technique but were arguing for a building "as light and open as possible. . . with glass ends." Although such a design was part of the Mission 66 planners' early concept, the museum branch's preferences had influenced preliminary planning and resulted in the alterations that so disappointed Cecil Doty. [44]

Despite strong approval from the WODC, Anshen and Allen's design had undergone revisions since its preliminary stage, and the architects were required to re-submit their plans to the park superintendent, regional office, museum branch, and Washington office. As Hein recalls, Director Wirth was torn between the opinion of the museum experts and that of the WODC. Wirth scheduled a design presentation in the San Francisco office, and after hearing the strong support of the Park Service architects firsthand, he accepted their consensus even though the working drawings submitted in November 1956 displayed no significant changes. The cylindrical element featured a pattern of vertical lines made by alternating strips of insulated glass, concrete panels, and areas of concrete masonry. [45] Its composition roof was topped with a plastic skylight. But the highlight of the design was certainly the massive glass wall on either end of the building. More than the butterfly roof or concrete ramp, the extensive use of glass and steel created an atmosphere suggestive of modern innovation. Porcelain enamel sandwich panels were installed near the base of these walls. The drawings also included plans for the traveling scaffold that was to be part of the working exhibit. The air conditioning and radiant heating systems were handled by Earl and Gropp, electrical and mechanical engineers based in San Francisco.

The "finish and color schedule" for the visitor center paints a colorful picture of the building's original interior surfaces. The visitor gallery walls and trim were surf green and the ceiling vernal green. The lobby was surf green with varnished birch trim, and the rotunda and stairway were also green. Offices had walls painted starlight blue and honey beige. Less significant spaces, such as corridors, vestibules, and storage spaces, were tusk ivory. These brightly painted surfaces were intended to relieve the monotony of the valley's gray surroundings and, perhaps, create the effect of an oasis in the desert. A similar effort would be made at the new facility in Petrified Forest National Park a few years later. [46]

During planning for the visitor center, the architectural firm was also busy with designs for employee housing and a utility building in the quarry area below the visitor facility. In June 1956, Hein drafted plans for the site, showing three residences and a four-unit apartment arranged in a small cul-de-sac of the road leading to the maintenance area. The buildings were one-story and the pitched roofs covered with asbestos shingles. A redwood fascia encircling the building under the roof line provided a decorative touch. Floors were specified as slabs covered in asphalt tile, and sidewalks and patios were of colored exposed aggregate concrete. Various drawings indicate that Park Service architects helped with this typical Mission 66 housing. [47] The concrete block utility building included areas for carpentry, auto maintenance, and equipment storage. [48]

Building the Visitor Center

The park sent out invitations for bids on construction of the visitor center in early February 1957, and by the closing date of March 19, had received multiple offers. [49] On April 23 the Department of the Interior issued a press release announcing that R. K. McCullough Construction Company of Salt Lake City would build the $309,000 building, which promised to be "distinctly different from those in other national park areas." In the second week of May, Park Service Project Supervisor R. Neil Grunigen reported that the McCullough Company was "erecting a field office, staking out the building and removing the old quarry structure." Excavation for the employee housing near the quarry was complete and contractors were beginning the concrete form work. Grunigen shared his reports with Superintendent Lombard and both consulted Lyle Bennett, WODC supervisory architect, on issues requiring official approval. [50]

After a month of work, the superintendent complained of slow progress—only fifteen percent of the site had been excavated—and the McCullough Company demanded a meeting with the architects. According to construction representative Lee Starke, delay in the delivery of structural steel resulted in early setbacks, as did waiting for Anshen and Allen to select colors for the block and concrete. By June, the contractors had excavated footings in preparation for beginning "forming and concrete work." [51] R. K. McCullough's superintendent, Duard Davis, had already requested an extension of time because revised drawings for the foundations had not been approved, delaying the order of structural steel. In the meantime, a local Vernal firm, Intermountain Concrete Company, began work on a contract for "roads and parking areas, bridge, base course, colored concrete and curb and gutter, timber guard rail, overlook and walk."

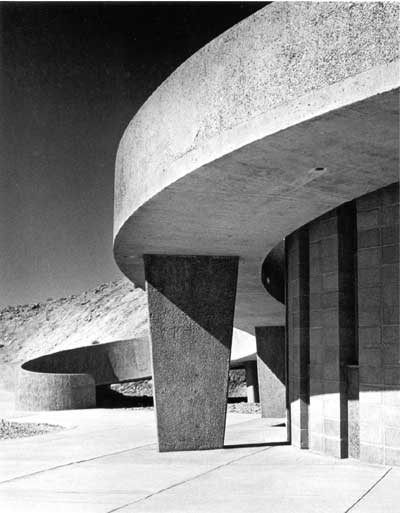

Despite the slow start, Superintendent Lombard reported much progress that Fall. The foundation wall was in place and exterior concrete "treated with acid to create a 'pebble' effect to blend with the rocky background." [52] Newspaper accounts reported details of the building's concrete construction—its glass walls with customized sun filters, and the fourteen-foot ramp wrapping around the side of the tower. By November, the structural steel framework had been erected and steel window sashes installed. Anshen and Allen selected "Mirawal's royal blue no. 202" as the color for the porcelain panels on the east elevation. Without its glass, the roof appeared a delicate steel cage. As winter approached, the "roof sheathing was on all the roofs and the built-up roofing applied on the circular element and low-wing areas." [53]Park Naturalist John Good reported that the building shell was "truly a massive thing." [54] In the month of December work shifted to the interior of the building, as contractors prepared to install wall coverings.

In his "narrative statement" on the building construction, Lee Starke mentioned the excellent relationship between the job superintendent and the contractor, who actually altered problematic aspects of the building without charging the government. A Mission 66 progress report written in March 1958 described the "exemplary accomplishment," emphasizing such technical details as the "Dusklite glass" panel walls of the exhibition hall that would "eliminate the reflection of the summer sun from the adjacent hills." [55] Quarry Visitor Center was completed on May 9, 1958. Along with the upcoming dedication of the building came news that Dinosaur might become a national park; coincidentally, the bill to achieve such status was part of the proposed Sputnik bill. [56]

Figure 15. Quarry Visitor Center, view from parking lot, ca. 1958. (Photo by Art Hupy, courtesy of Richard Hein.) |

The official dedication of Quarry Visitor Center, "Dinosaur Day," began at 2:00 p.m. on June 1. Guests gathered as the Uintah High School band played a celebratory prelude. After Governor George D. Clyde and Superintendent Lombard welcomed guests, Dr. LeRoy Kay, formerly of the Carnegie Museum, spoke about the natural history of the dinosaur quarry. Assistant Secretary of the Interior Roger C. Ernst delivered the dedicatory address. The ribbon cutting ceremony, a tour of the building, and a river boat trip followed. According to newspaper accounts, sixteen hundred people attended the event.

Figure 16. Quarry Visitor Center, view from beneath ramp, ca. 1958. (Photo by Art Hupy, courtesy of Richard Hein.) |

During the dedication ceremony, the architects appear to have become displeased with the color of the porcelain enamel panels located between the lower level entrance door and the maintenance door on the east facade. They offered to replace the nine blue panels with clear glass. Superintendent Lombard accepted the offer on the condition that the Park Service not incur additional expenses, but the firm was not willing to alter the building's aesthetics free of charge. The park eventually paid for this change.

Figure 17. Quarry Visitor Center, quarry face and upper level visitor gallery, ca. 1958. (Photo by Art Hupy, courtesy of Richard Hein.) |

In a report to the regional director, Superintendent Lombard noted that the public reaction to the building had been "most favorable" and that the park staff was "justly proud." [57] The building was featured on the cover of the July-August Geotimes, a magazine published by the American Geological Institute. For this organization, the building was much more than a Mission 66 achievement. As "the only place in the world where visitors can see bones in the rock and watch paleontologists at work," the building was a landmark educational facility. [58] For the architects, the design brought "national recognition" and "opportunities that made them a leading California firm." [59]

In Situ Interpretation

Considering the museum division's early role in the design of the building, it's not surprising that Anshen and Allen worked with the Western Museum Laboratory in San Francisco on exhibit plans throughout the visitor center. By design, the architecture of Quarry Visitor Center also involved museum interpretation; one wall of the building was an exhibit. The exhibits planning team submitted its designs for the lobby installations on May 3, 1957. [60] The interior walls of the lower gallery were to be furred and faced with gypsum board in preparation for painting. Exhibits were installed in recessed cases, shadow boxes, and in diorama form. A year later, the architects submitted preliminary drawings for the exhibit installation, plans that were not immediately accepted by Superintendent Lombard. According to John W. Jenkins, chief of the Western Museum Laboratory, museum staff red-lined the architects' drawings with suggestions for spacing between panels to improve visitor circulation, and although Anshen and Allen approved the changes, work on construction drawings awaited further discussion with the superintendent. Jenkins supported the firm's basic concept and praised the "excellent and very attractive plan . . . which would differ from most of the recent National Park Service installations . . ." In the meantime, Jenkins realized that the installation plan could not be completed in time for the dedication ceremony and agreed to supervise completion of a temporary exhibit. The architectural firm was also eager to submit its drawings of carpet-covered wooden benches and cubes for seating in the upper and lower levels. [61] The architects' working drawings for the exhibition gallery were finally accepted by Ralph Lewis in October 1958.

The excavation aspect of the quarry face exhibit would prove to be an ongoing project. It had actually begun in 1952, and, by 1963, geologists estimated another fifteen years of digging and scraping would be required to complete their work. The permanent monument staff included museum technicians and a Ph.D. museum geologist to carry out the excavation. Although fossils were removed from this area, a primary goal of the excavation was to prepare the north wall of the visitor center for public viewing. This 183- by 35-foot area, which formed a rock wall at a 67 degree angle, required "quarrying away the sterile rock, working the bone out in relief, and cleaning the surface with hand tools, and treatment of the fossil bone with a preservative." [62] Although paleontologists no longer chip away at the rock, their tools remain behind as part of the current exhibit. In 2000, the museum includes original exhibit panels and displays as well as more recent additions, such as a panel in front of the building describing the structure's architectural significance.

A Bentonite Foundation

The scenery at Dinosaur National Monument is colorful mineral deposits, valleys revealing strata millions of years old, and fantastic shapes carved into solid rock by centuries of erosion. For Mission 66 designers who might have become jaded by this environment, geological power made its presence known in the form of bentonite deposits underneath the visitor center. When exposed to water, bentonite sprang into action, expanding at a force strong enough to move steel girders. Even before the building was completed, the Park Service observed damage to the parking area. Radiating cracks were first observed and reported by Construction Foreman Davis in November 1957. [63] During the first year the building was open to the public, the park staff felt an unsettling vibration in the upper gallery. Lyle Bennett advised performing a vibration test on the balcony slab by placing wooden posts at several points under the overhang. According to Supervisor McCune Ott, who conducted the test, the vibration could only be corrected by installing a post at every beam, a solution unacceptable to the park. Since visitors weren't complaining about the vibration, however, no further action was taken.

In 1962, WODC drew up plans for the reconstruction of the plaza area in an effort to improve the drainage system. These included details of the roof drains and a longitudinal section showing the "typical subsurface drain." At this time, the Park Service installed an aluminum handrail on the ramp and laid down a cobblestone and concrete slab around and under the ramp, which was extended slightly. [64] Despite these improvements, the plaza continued to be a problem. In March 1966, the maintenance division regraded the ground on the north and south sides of the building, realigned the pavement slabs in the east plaza, installed steel pipeline for roof drainage, cut several French drains, and patched other problem areas. The next year, the San Francisco Planning and Service Center grappled with repairs to the visitor center building, which included replacing some of the existing footings with new twenty-foot-deep caissons. In addition, the Park Service extended the lower level lobby, installed new handrails in the gallery, and replaced several of the fixed-sash windows on the east and west wall elevations with operable sashes. [65]

The geological situation was not seriously analyzed until 1966, when Dames and Moore, consultants in applied earth sciences, revealed the presence of bentonite in the soil. Their evaluation indicated that additional damage could be avoided if moisture were kept out of the foundation. After the first intensive season of rain and snow, the bentonite began to move. [66] Eugene T. Mott, who had witnessed similar subterranean action at the Painted Desert Community, compiled a detailed description of the building's damaged areas after inspecting the structure in 1968. Mott's list included two pages of "widening floor tile joints," and cracks in walls and ceilings; the south wall may have settled two inches. Like his predecessors, Mott recommended removal of moisture in the foundation as the park's highest priority. But while others blamed bentonite, Mott thought that the loose, sandy soil around the building was the most likely cause of problems. According to his assessment, the "beautiful" building was "constructed properly"; it displayed solid workmanship and the design was "adequate for construction in a stable area." As far as the moisture problem, Mott had little advice but hoped to avoid a concrete border that would obliterate the landscaping around the building. [67]

Over twenty years later, a 1993 Park Service study reported that Quarry Visitor Center would have a very short lifespan if serious measures were not taken to solve drainage issues. Biannual reports on the water levels in the well holes and west manhole were requested. Even more recently, in 1997, Dinosaur was still "settling and moving," but the cause was determined as both bentonite and a subterranean fault. After structural evaluation, a team of Park Service specialists advised "an overall plan to manage and stabilize" the building, preferably supervised by an architecture and engineering firm or the Denver Service Center. [68]

Mission 66 Construction Continues

During the early years of Mission 66, several visitor centers were planned for locations throughout the park: a small facility at Pool Creek, "branch" visitor centers at significant points (actually elaborate wayside stations), and a headquarters with offices and general orientation materials. The headquarters/visitor center was controversial, not for its architecture, but because of its disputed location; both Utah and Colorado hoped to claim the new building. Even before the dedication of Quarry Visitor Center, Conrad Wirth directed a public hearing on Dinosaur's continuing Mission 66 program. Six years later, in 1964, a site was chosen in Artesia, Colorado. [69] The building was located off Route 40 at the junction of the road to Echo Park and a scenic viewpoint at Harpers Corner from which visitors could see the Yampa and Green Rivers flowing undisturbed through their ancient canyons. The Artesia Headquarters was as ordinary as Quarry Visitor Center was unusual. Its most defining characteristic, a veneer of rough-cut masonry, closely resembled the facade of a prominent downtown building. [70] Visitors approach a courtyard area equipped with restrooms and a covered patio. Beyond the comfort station is "oasis porch," an additional shaded space with benches, and to the left, the entrance to the visitor center lobby. Small interpretive exhibits share space with the shop and information desk. The auditorium on the right side of the building is still used to show the orientation movie. Park Service offices can be entered from the lobby, but are not part of the visitors' experience. Decked out in a colorful, highly textured masonry pattern, this visitor center could appear to be "harmonizing" with just about any park environment. Although unoriginal in terms of function, the building displays a comforting attention to detail and a permanence appropriate to its setting. The architects, Arthur K. Olsen & Associates of Salt Lake City, had recently designed a visitor center for Capitol Reef in Torrey, Utah.

Figure 18. Headquarters, Dinosaur National Monument, Artesia, Colorado, 1998. (Photo by author.) |

By the time Mission 66 planning at Dinosaur was focused on the Artesia Headquarters, Anshen and Allen were busy with a new visitor center in Sequoia National Park. Park planners were eager to develop a headquarters for the Giant Forest district because of its proximity to the Sequoia grove, and envisioned a facility with both visitor and administrative accommodations. As far as architectural style, the planning prospectus noted that the "present trend in design is toward conventional modernism." In their design for a woodland visitor center, Anshen and Allen managed to avoid convention without creating a spectacle. The Lodgepole Visitor Center appeared decades distant from the firm's futuristic work in the desert. With its peaked roof, rough wood paneling, and boulders, the building was a modernist version of a rustic lodge. But where the CCC might have used mortise and tenon construction and peeled log columns, Anshen and Allen chose steel bolts and girders. The roof was raised seam metal, the walls paneled, and the boulders not as bold as those gathered in the 1930s. Inside, the roof features exposed beams, the hallmark of the rustic interior. Even though rustic forms and techniques are imitated, the architects did not attempt to disguise their materials. As a result, they achieved a utilitarian interpretation of rustic suitable for a modern development program.

The firm of Anshen and Allen, overseen in 2000 by principal Derek Parker in San Francisco, has expanded its practice with offices in Los Angeles, Baltimore, Sarasota, and London. [71] The firm specializes in academic, advanced technology, healthcare, and commercial buildings, as well as large-scale planning. Recent international work includes the Guangzhou World Hospital in China, the New Norfolk and Norwich Hospital in the United Kingdom, and Cornwell House, King's College, London. In 1995 Anshen and Allen completed an addition to Louis Kahn's Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California. This design posthumously links the firm's founders, two University of Pennsylvania graduates, with their alma mater's most famous architect and one of the masters of modern architecture.

Although the Quarry Visitor Center remains essentially as it was during the Mission 66 era, the approach to the site has been significantly altered. Parking became a problem at Dinosaur as early as 1968, and in the early 1970s the entrance to the park was reconfigured to accommodate a shuttle service for use during peak hours. The new design involved obliterating a portion of the original spur road and building a new section with turn-offs to the visitor center parking lot and the residential and maintenance area. Today, visitors park about a mile from the site and walk a short distance to a covered area equipped with a comfort station, benches, and exhibit panels. A shuttle bus then carries them up the winding road and drops them off in front of the visitor center entrance. [72]

Quarry Visitor Center was listed in the National Register of Historic Places as part of a multiple resource nomination in 1986. [73] While other modernist Mission 66 buildings have been ridiculed for their flat roofs, concrete ramps, and cylindrical forms, Quarry Visitor Center receives more praise than criticism. Even as its foundation continues to move, the radical aspects of the building are accepted. One reason for this tolerance is that the modern style seems appropriate in the rocky, almost lunar environment of Dinosaur National Monument. Another reason for the building's success is its fulfillment of a larger purpose. The structure houses remains that are "living" exhibits; the site and its building are one. Modern achievements in the manufacture of tempered glass were a prerequisite of the design. Like many of the best modern buildings, Quarry Visitor Center succeeds not only because of design factors, but through the accidents of location and program. As time has told, modernist buildings are most admired when they fulfill a purpose no other style could satisfy quite as well. Quarry Visitor Center is such a building.

Although the new visitor center was not the first modern facility constructed by the Park Service, it was the most original and the most famous early example of its type. Major architectural journals featured photographs and copies of plans, and their articles included notice of the Mission 66 program. Director Wirth realized he was going out on a limb with Quarry Visitor Center, but felt that the "bold move" would result in a building of "world-renown" and "attract thousands of people." [74] In retrospect, this calculated decision not only helped protect Dinosaur from the threat of a dammed Echo Park, but also launched the development effort that Wirth believed the salvation of the National Park Service.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

allaback/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 26-Apr-2016