|

National Park Service

MISSION 66 VISITOR CENTERS The History of a Building Type |

|

CHAPTER 2

Wright Brothers National

Memorial Visitor Center

Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina

Although Mission 66 development was considered crucial for public use of national parks, its modern architectural style did not always coincide with social expectations for wilderness parks, battlefields, or desert locations. Park Service and contract architects attempted to conform to the regional landscape, address local traditions, and temper the modernist aesthetic with appropriate materials. If the national parks and monuments posed countless environmental challenges, however, the site of the first successful powered flight offered an ideal context for a modernist building. The wind-swept dunes of Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, suggested the clean lines of Mission 66 design, and, like the accomplishment it memorialized, the "new" architectural style represented innovation, achievement, and a future improved by technology. During the early 1950s, the Park Service designed an elaborate million-dollar aviation museum for the Wright Brothers National Memorial. Fortunately, funding could not be obtained for the proposed development, which would have overwhelmed the site with a sprawling modern complex. By 1957, the Park Service was ready to finance construction of a different type of facility. A new visitor center would centralize basic visitor services in a simple, compact plan. In accordance with Park Service practice, the modest visitor center would be built close to the "first flight" site, a location allowing visitors to view both the historic flight path and the memorial from the building's windows and exterior terrace. Small in scale and height, the building would not detract from the park landscape. The Wright Brothers Visitor Center was completed in the early years of Mission 66 and quickly became an example of what the development program could accomplish for a small park with limited resources.

The first organized preservation effort at the Wright Brothers site was launched in 1927 by the newly formed Kill Devil Hills Memorial Association. During its early planning stages, the Association imagined a future museum at the site, but a more immediate concern was the construction of an appropriate memorial atop its namesake sand dune. Congress authorized the Kill Devil Hill Monument National Memorial in March 1927, and the cornerstone for the structure was laid during the next year's anniversary celebration. Rodgers and Poor, a New York architectural firm, designed the 60-foot-high Art Deco granite shaft in 1931-1932. [1] Crowned with a navigational beacon accompanied by its own power house, the tremendous pylon was ornamented by bas-relief wing designs. [2] Kill Devil Hill was not the site of the Wright Brothers' achievement, but the launching point for earlier glider experiments and a location closer to the heavens than the Wrights' primitive airstrip on the flat land north of the dune. When the Wrights set up camp here from 1901-1903, this land was constantly shifting sands. The Quartermaster Corps used sod and other plantings to stabilize the sand hill when the area was still under the jurisdiction of the War Department. [3] In addition, the Kill Devil Hills Association marked the location of the first flight with a commemorative plaque. During the 1930s, plans for the Memorial included a park laid out in the Beaux-Arts tradition, with a formal mall leading to a central garden flanked by symmetrical hangers and parking lots. [4] An airport served as the flat land terminus of the axis, and the Kill Devil Hill memorial as its culmination; six roads radiated out from the monument to the borders of the park. Although this scheme was never implemented, the system of trails and roads constructed by the Park Service in 1933-1936 formed the basis for today's circulation pattern. A brick custodian's residence (1935) and maintenance area (1939) were built south of the hill.

When the monument was planned in the late 1920s, Congressman Lindsay Warren imagined a museum "gathering here the intimate associations," and "implements of conquest." [5] Almost twenty years later, an "appropriate ultra-modern aviation museum" was proposed for Wright Brothers during the effort to obtain the original 1903 plane, but funding was not forthcoming. [6] Such an ambitious construction project began to seem possible in 1951, when the memorial association reorganized as the Kill Devil Hills Memorial Society, and prominent member David Stick established a "Wright Memorial Committee." Stick realized that a museum could only succeed with assistance from the National Park Service, local boosters, and corporate sponsors. Among the committee members recruited for the development campaign were Paul Garber, curator of the National Air Museum in Washington; Ronald Lee, assistant director of the Park Service; and J. Hampton Manning, of the Southeastern Airport Mangers Association in Augusta. In preparation for the first meeting, the Park Service drafted preliminary plans for a museum facility dated February 4, 1952. [7] Regional Director Elbert Cox introduced the project as a "group of buildings of modern form" to be located off the main highway northeast of the monument. The proposed Wright Brothers Memorial Museum included a "court of honor," "Wright brothers exhibit area," "library and reception center," and funnel-shaped "first flight memorial hall" with outdoor terraces facing the view of the first flight marker to the north and Wright memorial marker to the west. The exhibit galleries were to contain "scale models of the various Wright gliders and airplanes, a topographic map of the area at the time of their experiments, scale models of their bicycle shop and wind tunnel, and photographic and other visual exhibits." [8] One wing of the complex housed offices for the museum curator and superintendent, workshop and storage rooms, and a service court. In elevation, the northwest facade is multiple flat-roofed buildings adjacent the double-height memorial hall, a slightly peak-roofed room with glass and metal walls.

Although it could not provide adequate funding for the museum, the Park Service entered into the planning process in earnest, producing revised plans and specifications in August 1952. Director Wirth looked "forward with enthusiasm to the full realization of the . . . program," and promised that the Park Service would operate and maintain the facility once constructed. [9] He even included cost estimates for the buildings, structures, grounds, exhibits, furnishings, roads, and walks. [10] During the summer, word of a potential commission spread and several regional architects notified Stick of their design services. [11] Despite much effort, however, the committee was unable to raise funds for the million dollar complex, which was originally slated for completion by the fiftieth anniversary. Several smaller goals were achieved in time for the December 1953 celebration: the monument was renamed the Wright Brothers National Memorial, entrance and historical markers established, and reconstructions of the Wrights' living quarters, hanger, and wooden tracks constructed. Though disappointed at the lack of financial backing for the museum, the committee "strongly felt that the original plans for the construction of a Memorial Museum at the scene of the first flight should remain an objective of the Memorial Society." [12] The establishment of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, also in 1953, may have contributed to their continued optimism.

Four years after the committee's initial attempt to fund an aviation museum, the National Park Service surprised all concerned with an offer to sponsor a scaled-down version of the facility. The committee met in Washington on October 23, 1957, only to learn that funds from the aircraft industry would not be forthcoming. During this meeting, Conrad Wirth outlined his Mission 66 program and revealed that a visitor center at Wright Brothers was included among the proposed construction projects. After further consideration, Wirth promised to make the Wright Brothers facility an immediate objective "by shifting places on the list with one of several battlefield visitor centers planned in advance of the forthcoming Civil War centennial." [13] Just four years earlier, the Park Service had planned a modernist museum for the site on the scale of a Smithsonian, with the free-flowing design of a public building typical of the period. The visitor center of 1957 did not have the aesthetic freedom of a such a museum. For its Mission 66 visitor center, the Park Service sought a smaller, less expensive, more compact structure with distinct components: restrooms (preferably entered from the outside), a lobby, exhibit space, offices, and a room for airplane displays and ranger programs (in place of the standard audio-visual room or auditorium). As designers of the new building, the Park Service chose a new architectural firm based in Philadelphia: Mitchell, Cunningham, Giurgola, Associates, which was soon known as Mitchell/Giurgola, Architects. [14] With its symbolism of innovation, experimentation and evolving genius, the building was an ideal commission for the fledgling firm.

Mitchell/Giurgola,

Architects

The Wright Brothers Memorial Visitor Center was the "first building to achieve nationwide recognition" designed by Ehrman Mitchell and Romaldo Giurgola. [15] Although only a year old in 1957, the visitor center building type was not unfamiliar to either young architect. Mitchell and Giurgola met in the office of Gilboy, Bellante and Clauss, a Philadelphia firm commissioned to design the 1955-1956 visitor centers at Jamestown and Yorktown. [16] During Gilboy, Bellante and Clauss' association with the Park Service, Mitchell and Giurgola became acquainted with John B. Cabot, chief architect of the Eastern Office of Design and Construction. In October 1957, Mitchell invited "Bill" Cabot to a cocktail party at the family's new home in Lafayette Hill, Pennsylvania. The two discussed the prospect of Park Service work for the untested firm of Mitchell/Giurgola. As Mitchell recalls, Cabot said, "Mitch, don't call me, push me, pressure me . . . if I get work, I'll call you." [17] A few months later, Cabot did call. When Mitchell questioned the Chief Architect about his choice of virtually unknown architects for the prestigious commission, Cabot said that the recent recession in the Eisenhower administration affected his decision: "We got a directive to get every project on the street. We had eight projects and seven architects." [18] If Mitchell/Giurgola obtained the Wright Brothers Visitor Center contract by being in the right place at the right time, the results they achieved far surpassed the Park Service's expectations. The publicity the building would receive in popular architectural journals over the next decade resulted not from the architects' reputation as accomplished modernist architects, but from the design of their building.

Born in Italy in 1920, Romaldo Giurgola was educated at the University of Rome and, beginning in 1950, at Columbia University. He taught at Cornell and served as an editor of Interiors magazine before joining the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania in 1958. Ehrman B. Mitchell, Jr., a Pennsylvania native born in 1924, received his architectural education at Penn and a position with a local firm soon after graduation. Three years later he joined Gilboy, Bellante and Clauss of Philadelphia and in 1951 became the supervisor of the firm's London office. His work in England included coordinating with a large English consulting firm in the design of military air fields. When Mitchell returned to Philadelphia by the mid-1950s, he was experienced in running international architectural firms. In 1957, he and Giurgola began planning their partnership, and with the prospect of work from the Park Service, opened their own Philadelphia office. Along with the visitor center commission, the firm designed two other public buildings, several residences, and projects for competitions during its first few years in business. [19] When Giurgola became chairman of Columbia's architectural department in 1966, the firm opened a second office in New York. By this time Mitchell/Giurgola was a well-known architectural presence with an award-winning parking garage and the much sought after commission for the A.I.A. headquarters building in Washington, D.C., to its credit. [20] Ten years later, the partners would receive the A.I.A. firm award, the organization's most distinguished award for an office. The bicentennial year also marked the dedication of Mitchell/Giurgola's second Park Service structure, the Liberty Bell Pavilion on the mall across from Independence Hall. [21] Among the firm's many significant achievements are the headquarters building of the United Fund in Philadelphia (1971), of which one architectural historian declared "one has but to travel up and down the east coast of the United States to see the influence it has had on urban architecture." [22] Mitchell served as president of the A.I.A. in 1979-1980, and in 1982, Giurgola was awarded the A.I.A. Gold Medal, the highest honor bestowed upon individual architects. The Wright Brothers Visitor Center was not only featured in the A.I.A. nomination, but as part of a traveling "Gold Medal Exhibition" sent to schools across the nation. [23] Architectural historians assessing the firm's career look to this building as the beginning, and, as their first significant work, a benchmark from which to judge future growth and change. [24]

The Wright Brothers Visitor Center commission not only inspired Mitchell and Giurgola, but, more importantly, proved a challenging design problem worthy of national recognition. Like a handful of other park sites, the Wright Brothers Memorial is a monument to scientific and technological achievement. For the architects, as for the public, its value lay both in its significance to the history of aviation and to the more personal story of perseverance and experimentation leading to scientific progress. During the 1950s, when many of the country's first modern airports were under construction and the dream of space travel became a reality, aviation facilities used modern technology and materials to create aesthetic representations of flight, suggesting the limitless future of transportation. One early example, the terminal building at Lambert-St. Louis Airport designed by Minoru Yamasaki with George Hellmuth and Joseph Leinweber (1953-1956), housed terminals in three concrete groin-vaulted buildings with glass and aluminum forming the semi-circular walls of the remaining space. By the beginning of the Mission 66 program, Eero Saarinen, creator of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, was busy with plans for the TWA Terminal at Kennedy International Airport, New York (1956-1962), and Dulles International Airport, Reston, Virginia (1958-1962). In November 1957, park employees sent bags of sand from Kill Devil Hills to Los Angeles for the dedication of the city's "Jet-Age Expanded International Airport." [25]

Along with social change, the early 1960s brought restlessness among elite designers and a readiness for new leaders in the profession. In 1961, architectural critic Jan Rowan used the term Philadelphia School to describe what he hoped would become an exciting new direction in the practice of architecture. Architectural historians of today are equally eager to group Mitchell/Giurgola in this innovative "school" and to compare their work with the designs of Saarinen and others. As Ehrman Mitchell recalls, he and his partner were not thinking about modernist philosophy during their work at Wright Brothers, nor were they particularly interested in striking out in a new direction. The architects approached the Wright Brothers commission as a "natural response to conditions of program" and were motivated by "the quest for modern design." The overwhelming challenge was to portray the idea of flight in a static form. Mitchell/Giurgola's unconsciousness of any deliberate attempt to remake modernism was an early indication of their originality and key to their successful practice.

In theoretical discussions following construction of the visitor center, Mitchell and Giurgola explained how the firm was both modernist and critical of the standard tenants of previous modern design. As important as their built work, the theory and projects of Mitchell/Giurgola not only influenced generations of student architects, but inspired the flagging profession with new hope. Mitchell and Giurgola considered themselves '"inclusivist'" in their architectural theory and were convinced that a '"partial vision'" in design presented a more acceptable view of reality than the elitist and exclusionary practices of past modern architecture. [26] The young architects began their career at a time when severe modernist architecture seemed to lack the vim and vigor of real life. The work of Philadelphia architect Louis I. Kahn offered exactly what was missing: a sense of order and a reason for being. Kahn passed on his architectural theories in lectures at the University of Pennsylvania and in his buildings; construction began on the University's Richards Laboratories in 1958, the year Giurgola joined the faculty. Energized by Kahn's work and their shared experience at Penn—Mitchell, Giurgola, Robert Venturi, Robert Geddes, and other young architects emerged as a new force in the profession. By the mid-1960s this "Philadelphia School" was considered on the cutting edge of architectural design. As Rowan described it, the Philadelphia School responded to the modernist work of such icons as Richard Neutra and Mies van der Rohe. In place of the abstract forms and universal principles of the previous generation, the younger architects gravitated toward Kahn's more personal and sensitive design philosophy. The close relationship between Mitchell/Giurgola and Kahn is illustrated by the writings of Romaldo Giurgola, who not only became an ardent follower, but a scholar of Kahn's work. Closer study of Giurgola's writings helps to show how Kahn influenced the firm's attitudes toward place, community, and landscape and their expression through the use of light and attention to building materials. [27]

Although their first major building, Mitchell/Giurgola considered the Wright Brothers Visitor Center an important example of their architectural philosophy; the design is clearly a response to the methods of their predecessors and to the new possibilities outlined by Kahn. In a 1961 reference to the design methodology employed at Wright Brothers, Giurgola explained that the "order will be the participation in the environment of the building's special theme, not the imposition of abstract forms." [28] The same year, when interviewed for Progressive Architecture, Giurgola spoke about the role "subjective experience" played in the design process, a subject considered taboo to the blatantly objective proponents of the International Style. [29] The article included a full-page detail photograph of a segment of the visitor center illustrating the contrast of wood panels and concrete, close-ups of the entrance and ceremonial terraces, and smaller views of the overall building and plan. With the exception of Quarry Visitor Center at Dinosaur, completed in 1958, the Wright Brothers Visitor Center received the most media coverage of any National Park Service project of its type.

The Philadelphia office of Mitchell/Giurgola, Architects became MGA Partners in 1990. The principals of this successor firm—Alan Greenberger, Daniel Kelley, and Robert Shuman—worked with the founders beginning in the 1970s. MGA Partner's current projects include the Gateway Visitor Center on Independence Mall, a new facility slated for completion in 1999, the Children's Discovery Museum of the Desert in Rancho Mirage, California, and a theater and drama center for Indiana University in Bloomington. The firm also inherited records and drawings from past projects, most of which have been transferred to the Architectural Archives at the University of Pennsylvania. The New York office retains the original name "Mitchell/Giurgola." In 2000, Ehrman Mitchell is retired and living in Philadelphia. Romaldo Giurgola lives in Australia, where he is a partner of Mitchell/Giurgola & Thorp Architects of Canberra and Sydney.

Designing the Visitor

Center

During his speech at the 1957 First Flight Anniversary ceremony, Conrad Wirth described "major developments" scheduled for Wright Brothers Memorial over the next two years. The Park Service planned to proceed immediately with construction of a new entrance road and parking lot for the visitor center. Actual construction of the visitor center would begin during the next fiscal year. The new building would "accommodate visitors in large numbers . . . provide for their physical comforts . . . and present the story of the Wright Brothers at Kill Devil Hill in the most effective way graphic arts and modern museum practice can do it." [30] Wirth's remarks seem innocent enough, but the new building transformed the visitor experience at Wright Brothers. As historian Andrew Hewes pointed out in 1967, the focus of site interpretation shifted from the memorial shaft to the visitor center. The interior of the shaft and a stairway to the top of the monument had been open to visitors since its creation, but in 1960 access was closed. During an August 1958 committee meeting, members agreed that "special consideration be given to directing people to the first flight area rather than to the memorial feature." [31]

Excitement over what shape the visitor center might take increased after the groundbreaking at the anniversary ceremony. According to Superintendent Dough's monthly report, "Mr. Benson of EODC and Messrs. Mitchell, Cunningham and Giurgola" visited the site on March 15 "in order to work up final drawing plans for the visitor center." These were actually preliminary design studies, the first of over one hundred sketches and drawings created for the visitor center. The next month, "Messrs. Tom Moran, Harvey H. Cornell (landscape architect), Donald F. Benson and others" gathered to discuss the location of the visitor center and parking area. The Superintendent included an uncharacteristically lengthy comment on the results of these meetings:

The final plan reflects contributions from the Washington, Region One, EODC and Memorial offices as well as contributions of members of the architectural firm preparing the plans. It always impresses us to witness the Service planning a development as a team; wherein, after an exchange of ideas, the end product is better than any one individual or office could plan. [32]

This collaborative effort took shape in the Park Service's development drawings of Route 158 (still under construction), the entrance road to the monument, the parking lot, visitor center footprint, and paths to the quarters and hanger. [33] The location of these features and the connections between them were approved by John Cabot, Regional Director Elbert Cox, Thomas Vint, and Conrad Wirth between April and June 1958. As the Mission 66 report for the park emphasized, the visitor center was to be "within the Memorial near the camp buildings" and a trail would lead from the facility to the first flight area. [34] Mitchell corroborated that the siting of the building was entirely a Park Service decision. The site was "exactly what they dictated. The location was specified as being close to the flight line." In a recent letter, Giurgola agreed that the site "was carefully planned while working closely with the NPS." [35] The Park Service wanted the public to stand under the dome and be able to see the monument and first flight markers from inside the building. [36]

Mitchell/Giurgola's early sketches on yellow trace, produced in March and April 1958, included several very different ideas for the overall plan of the building and its exhibition space. In one case, the architects envisioned an office wing separated from the rest of the building by a landscaped courtyard; the gallery was two stories. They also considered placing the central lobby and information area between an office wing and exhibit gallery. A version of the compact organization that would become their final choice was considered in March but not accepted until later in the design process. The architects' proposals for the double-height gallery and fenestration demonstrated their interest in creating dramatic effects of light and shadow, not to mention maximizing the opportunity to frame specific exterior views. Fenestration possibilities ranged from triangular mullion designs to vertical and horizontal patterns on the upper half of the exhibit space. These window arrangements were coordinated with first-floor windows, usually of a contrasting design. One perspective shows this gallery as a glass-walled cylinder; another slices a parachute-shaped roof open in the center and inserts a half-moon of glass. In some of the sketches the architects used brilliant colors—bright white, yellow and turquoise—to emphasize the contrast between translucent and solid sections of the window walls. Subtle changes in the patterning of window facades and ceilings altered the effect of mass, causing the gallery to "float." Throughout their artistic experiments, Mitchell and Giurgola were considering the location of the building in relation to the hilltop monument and the flight area. Preliminary site sketches include arrows indicating vistas from the building to these points of interest. The firm's early design efforts demonstrate a wide range of possibilities, but none that compare with the final plan in terms of clarity of program, circulation, and function. [37]

While the architects worked with possible design schemes, the park turned its attention to construction of the parking facilities accompanying the new building. In June the contract for the new entrance road and parking area was awarded to Dickerson, Inc., of Monroe, North Carolina, for the low bid of $73,930. The 0.56 mile road and parking area was to be completed within two hundred and fifty days. A group of EODC architects and landscape architects—Zimmer, Moran, Roberts, and McGinnis—visited in August "to discuss plans for the Visitor Center and Parking Area." [38] As Dough remarked, "the completion of the road project will pave the way for the building contractor." [39] The planning for the visitor center project also provided the incentive to finalize a land acquisition deal for which state funds had already been allotted. Congress authorized the Memorial's boundary expansion in June 1959, adding an additional one hundred and eleven acres to the park. [40] This extension provided the additional land to the east and north of the building necessary to include the fourth landing marker and parking lot.

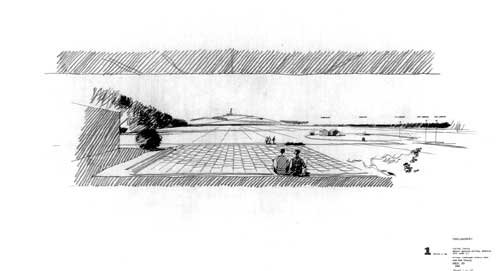

Figure 19. Wright Brothers Visitor Center. This view of the memorial and flight markers from the ceremonial terrace was a preliminary drawing completed in August 1958. (Courtesy of National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The preliminary plans submitted by Mitchell/Giurgola at the end of the summer were visually pleasing as well as instantly readable. The initial sketch in the series only depicts the building's ceremonial terrace, the roof overhang, and the edge of the lobby framing a panoramic view of the monument, barracks, and take off and flight markers. The final plan organized the elements of the program within a square, avoiding the potential monotony of such geometry by alternating interior spaces with open exterior terraces. The architects' early sketches suggest that their artistic exuberance might have been a little shocking to their Park Service clients. Perhaps in an effort to temper the more unusual aspects of the design, Mitchell/Giurgola produced several more subtle sketches. In elevation, the shell roof appears to diminish; from some angles it appears to dominate the structure, but as the building is approached, the dome gradually levels out and almost disappears. Among the preliminaries is a view of the building and the distant Wright Brothers monument against the night sky. Two-thirds of the paper is black and the building barely distinguishable among the trees and gentle rise of the horizon. Attention is focused on the road leading into the park, an exiting car, and a car passing by on the main highway. [41]

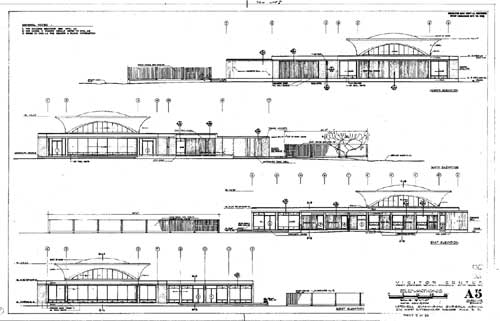

Figure 20. Wright Brothers Visitor Center, presentation drawing, 1959. (Courtesy of National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The Park Service invited Stick and his committee to a meeting for review of the preliminary plans of the building and exhibits on July 28, 1958. In August members of the committee awaited copies of the revised building plans. A misunderstanding prevented Mitchell/Giurgola from beginning the working drawings, and when Cabot asked about their progress in late September, they were stunned. Despite this slow start, the architects rushed to complete the required drawings by the December 7 deadline. The working drawings essentially refined the designs presented earlier, but the cover sheet depicts an unusual perspective of the floor plan. The axonometric aerial view emphasizes the extent of window space, shown as thin, solid lines, in contrast to the three-dimensional walls. A plan and elevation appeared in a February 1959 "news report" in the popular journal Progressive Architecture. The short description, "Two Visitors' Centers Exemplify New Park Architecture," noted that "the design of visitors' facilities provided for national tourist attractions seems to be decidedly on the upgrade, at least as far as the work for the National Park Service is concerned."

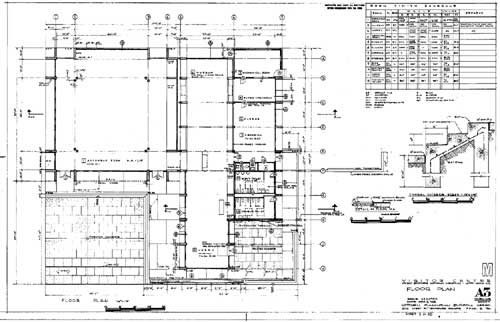

Figures 21 and 22. Wright Brothers Visitor Center. The plans, sections and elevations of the building were completed in December 1958. (click on images for larger size) |

Perhaps not coincidentally, the other visitor center pictured was the work of Bellante & Clauss at Mammoth Cave National Park. [42] Later that year, the architects submitted a presentation drawing, complete with a small boy flying a toy plane in front of the ceremonial terrace, and a twelve-inch sectional model of half of the exhibit hall (see figure 20 on page 77). The model effectively demonstrated the building's innovative air circulation system with a cut-away view of the duct in the assembly room. In section, the concrete dome appeared lighter and more "wing-like" than depicted by drawings.

As December 7 approached, the committee began planning for its annual celebration, combined this year with the observance of the 50th anniversary of the United States Air Force. The committee hoped that a ground breaking or cornerstone laying ceremony might be included in the festivities. A month earlier, Lee reported that the final drawing for the visitor center was not complete and, therefore, the accurate laying of a cornerstone impossible. [43] The Park Service chose to initiate the Mission 66 program at Wright Brothers with a speech by Conrad Wirth outlining improvements scheduled for the Memorial over the next two years. Wirth had the honor of digging the first shovel of earth at the site of the future visitor center with a silver spade. [44]

In a one-sheet resume promoting Mitchell/Giurgola, written a few years after the visitor center dedication, the architects described the Wright Brothers commission as "among our major projects" and went on to discuss its design in some detail. The "dome-like structure over the assembly area," though technically "a transitional thin shell concrete roof with opposed thin shell overhangs connecting the perimeter of the structure to form a complete monolithic unit," also had a symbolic role. The roof structure design "admirably serves to allow light into the display area of the aircraft to give this area a significant character as well as forming a strong focal point on the exterior of the structure which stands above the low-lying landscape, in concert with the higher rising dunes and pylon." Evidently, the north concrete wall of the entrance terrace had been the subject of considerable public speculation. Here, and in their resume, the architects explained that the patterned wall was intended "to be an expression of the plastic quality of concrete by means of well-defined profiles, recessions and protrusions, simply placed to form an integral pattern over the wall surface." Not only did the wall feature rigid and curved shapes, but also contrast in depth and surface, as sections of the wall were bush hammered. In effect, the concrete patterned wall was public art. [45]

The attention lavished on aesthetics and symbolic purpose, as described by Mitchell/Giurgola, did not detract from the visitor center's practical function. Visitors appreciated the straightforward approach to the building from the parking lot and the exterior restrooms adjacent the entrance terrace. They may not have noticed the unusual shape of the drinking fountains, with their molded concrete basins, or paid much attention to the undulations and protrusions of the sculpted wall. But even at the most basic level, these design elements suggested the free-flowing form of both sand dunes and objects that fly. The entrance terrace was also part of the 128-foot-square concrete platform elevating the entire building a few feet above the ground. Steps extended to either edge of the terrace, and visitors crossed the open area to reach the double glass doors leading into the lobby. At this point, visitors were also invited to walk around the building to the ceremonial terrace. The entrance facade was full-height steel-framed windows divided by concrete piers, a pattern of bays encircling the building. Similar windows formed the far wall of the lobby, which could be seen by looking through the building from the terrace.

Upon entering the visitor center, attention was immediately directed towards the ceremonial terrace outside and the first flight monuments beyond. The Park Service information desk was actually located behind the visitor at this point. Since the lobby space flowed into the exhibit room, visitors gravitated to this area after taking in the view. The walls of the exhibit area were entirely covered with vertical tongue-and-groove cypress boards and wood paneling. This interior treatment, combined with the lack of windows, resulted in an inward-looking museum space conducive to study. [46] Park offices were located to the left of the exhibit area. Once visitors had followed the exhibits in a rectangular pattern around the museum, they found themselves at the entrance to the assembly room. In contrast to the muted tones and contemplative mood of the museum, the assembly room was a double-height space full of light from the three clerestory windows in its shell roof and the floor-to-ceiling windows on three sides. The shell roof, the 40-foot-square shape of the space, and the square mirrored above in the corrugated concrete overhang also emphasize the importance of the replica 1903 flyer in the center of the room. This assembly area was intended to substitute for an audio-visual or auditorium space, and in their presentations, Park Service interpreters would not only use the plane as a prop, but point out the flight markers, hangar and living quarters, and distant hilltop monument. Double doors at either end of the south facade led out to the ceremonial terrace. When groups gathered here for the annual celebration and other events, the Memorial's significant features stood in the background.

Although the interior contrasts in ceiling height and the amount of light emitted into the spaces belies the fact, the visitor center's walls are divided into equally spaced bays; whereas the assembly room is all glass, however, the office and exhibit spaces alternate cypress wood panels with sections of treated concrete. The faces of the piers are bush hammered. These surface contrasts force the visitor to pay attention to the composition of materials: the durable cypress wood, traditionally used in boat building, and the color and texture of the aggregate, which includes sparkling chunks of quartz and other arresting stones. In theory and practice, the Wright Brothers Visitor Center was a balance between aesthetics and function.

Figure 23. Wright Brothers Visitor Center, view of "patterned wall" from entrance, 1999. (Photo by author.) |

The best example of Mitchell/Giurgola's concern with aesthetically pleasing structure is also the least noticeable. The mechanical systems for heating and cooling the building were "inconspicuously incorporated" into the building. Progressive Architecture was particularly interested in the "water-to-water heat pump" that both took advantage of the oceanfront location and eliminated the need to compromise the building's "vast horizontality with a vertical stack." [47] Fan-coil units and ducts were hidden above a suspended ceiling in the lobby and museum, but in the assembly room, they became part of the interior decoration. The corrugated concrete overhang houses ducts that pull in fresh air from outside, and the "soffit" below is a "continuous slot" for return air. Frederick W. Schwarz of Morton, Pennsylvania, was the consulting engineer for the heating and air conditioning system.

Building the Visitor

Center

Donald Benson remembers the prospect of a modernist visitor center on the Outer Banks of North Carolina as more controversial than the colorful beach shelter he designed for Cape Hatteras National Seashore a few years earlier. The shelter's sun shades rose out of the beach like sculptures, but such artistic license was acceptable in a recreational facility devoted to seaside entertainment. In contrast, the visitor center was expected to be functional, dignified, and a public building for the local community. If the Park Service was now familiar with the Mitchell/Giurgola design, local contractors must have been surprised when sets of plans and specifications were sent out for bidding in January 1959. [48] Modern architecture was not part of the design vocabulary of the region, nor were modernist buildings prevalent in the state of North Carolina. [49] Bids were opened on February 4, 1959, and the contract was awarded to Hunt Contracting Company of Norfolk, Virginia, for their offer of $257,203. [50]

Construction of the visitor center began in March 1959, and foundation piles had been driven by the end of the month. In early spring, the beam forms were at grade level. Superintendent Dough predicted rapid progress now that "the slow process of getting the building staked out, supplies on hand and work organized has been completed." [51] Concrete columns and piers were erected in June and most of the floor slabs poured. On July 24, the contractors' work was inspected by Tom Vint, chief of design and construction, and Chief Safety Officer Baker, both of the Washington office. [52] By the end of the summer, the east elevation had begun to take shape. A view from the south shows the beams for the exhibit room standing apart from the office wing. The next month, contractors were laying the ribbed ceiling forms for the corrugated concrete overhang around the perimeter of the assembly room. [53] The major concrete portions had been cast, and Mitchell and Giurgola may have witnessed some of this form work during their "field inspection" at the site on September 24-25. [54] Form work for the patterned wall was well underway by October. A steel grid was used to create the protruding shapes on the surface of the wall. While the decorative wall was under construction, contractors were also assembling the arch beam forms of the dome. The general shape became visible in November; a plywood shell framed the central half sphere, and intricate interior scaffolding supported the dome framework throughout this construction. Engineer Don Nutt of EODC witnessed the "dome pour" later in the month. Smooth reinforced concrete covered the central portion first. The contractors then turned to form work for the "flange overhangs," which were subsequently poured. The dome sat on four coupled columns and was "tied" at its base by four tension rods. A December photograph of the assembly room interior shows the completed dome and semi-circular windows, the supportive scaffolding removed.

Despite colder temperatures, contractors were able to pour the steps of the visitor center in January 1960. Chief of EODC Zimmer and Supervising Architect Cabot spent two days "reviewing progress and details" of the construction that month, and Don Benson and Ann Massey, both of EODC, visited the site to discuss color and design. [55] Interior framing was still exposed in February, but the dome, overhang, and exhibition area roof were considered complete. Roofing compound was applied to the lobby section of the visitor center the next month, although glass sections of the building remained empty. Wall panels and windows were not installed until April, when engineer Don Nutt and landscape architect Ed Peetz (EODC) visited for a construction review. Sometime during the month, the contractor made his third estimate for a completion date, settling on June 10. The final inspection of the visitor center took place on June 20, 1960. Evidently no major changes were required, and specialists from the museum division were busy installing the twenty-two museum exhibits during the first weeks of July, when work also began on the surrounding landscaping. [56]

Figure 24. Wright Brothers Visitor Center, exterior view looking north, ca. 1960. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The contractors for "planting and miscellaneous construction"—Cotton Brothers, Inc., of Churchland, Virginia—had replaced existing concrete walks and additional pathways by mid-August. Landscape work involved grading and spreading topsoil as well as "considerable experimentation and effort . . . with native groundcovers." After completing the walks, seeding, planting tubs and flagpole base, the contractors began work on the wooden fence. Progress was interrupted by Hurricane Donna, which struck September 11 and leveled sections of the fence, but repairs were accomplished by the end of the month. In addition, the contractors planted twelve varieties of trees and provided plants for inside the museum. Before the final inspection, Cotton Brothers installed the Park Service's signs and gate. [57]

Figure 25. Wright Brothers Visitor Center lobby, ca. 1959. (Courtesy MGA Partners, Architects, Philadelphia.) |

The Wright Brothers Memorial Visitor Center was officially opened to the public on July 15, 1960. By all accounts, the building met with a positive reception. Superintendent Dough wrote that "hundreds of compliments have been received about the exhibits and the building's design since it was opened. Visitors are generally surprised to learn of the aeronautical principles formulated by the Wrights, and the descriptive term 'beautiful' is used repeatedly in describing the building." He also noted that although about two thousand visitors passed through the visitor center every day during the summer season, "these are so well distributed during visiting hours that there are seldom over 75 visitors within the building at a time . . ." [58] During the month of August, the site received 62,177 visitors, a 34 percent increase since the year before, and approximately three thousand more visitors than visited in August 1998. [59] Although Dough seemed optimistic about these figures in his initial report, by September he had become concerned about the "too interesting" museum exhibits, which he blamed for causing congestion in the visitor center. On five peak days ". . . 3,500 plus jammed into the visitor center." Dough indicated that the Park Service had not expected such crowds until 1966, as shown by graphs included in their Mission 66 prospectus. Rather than consider a building expansion, however, Dough suggested changing the exhibition layout: "More museum exhibits to further spread out the visitors may be the answer, but in our view the law of diminishing returns sets in when many more than about 19 exhibits are installed in a visitor center." [60] Mission 66 planning documents indicate that the Park Service anticipated record numbers of visitors—nearly ninty thousand per month by 1966—and judged the visitor center facility adequate to serve their needs. [61] By that time, Dough had retired and Superintendent James B. Myers assumed his post.

Dedication of the Visitor

Center

The exterior appearance of the visitor center was significantly altered by the end of the summer, with the completion of the wooden fence shielding the parking area from a clear view of the first flight markers and buildings. In preparation for the dedication, landscape architect Lewis from EODC "inspected new planting and miscellaneous construction," and the Park Service's supervisory architect, Judson Ball, reviewed the state of the visitor center. [62] By September the walks from the visitor center to the camp buildings and the main entrance gate were complete. The information desk for the lobby was delivered and installed, and planning for a permanent display of a Wright glider replica continued. [63]

The Wright Brothers Memorial Visitor Center was dedicated on December 17, 1960, the 57th anniversary of the first flight. According to one news account, a "slim audience saddened by Friday's airliner collision over New York and Saturday's crash at Munich" attended. [64] The most memorable moment in Mitchell's recollection of the event was a speech by Maj. Gen. Benjamin D. Foulois, who actually watched the Wright brothers test their early planes and flew the country's first army aircraft. Local papers covering the dedication had only compliments for the new visitor center building, and by early December over one hundred thousand visitors had already passed through its doors. [65]

If the Wright Brothers' legacy was the main focus of dedication day, over the next few years the visitor center building would become the subject of its own articles and press releases. Progressive Architecture had given notice of the design in 1959 and, in 1961, included a floor plan, photograph of the finished building, and close-ups of the concrete wall and terrace design in its profile of "the Philadelphia School." [66] Two years later, the "Kitty Hawk Museum" was a feature of the journal's August issue. The building received praise for its orientation and planning of interior spaces that "make visiting this national park an aesthetic as well as an instructive experience." [67] Washington Post architectural critic Wolf Von Eckardt called the visitor center a "simple, but all the more eloquent, architectural statement that honors the past precisely because it does not ape it." [68] The Wright Brothers Visitor Center was also singled out in "Great Builders of the 1960's," a special section of the international publication Japan Architect (1970), in the AIA Journal's 1971 assessment of Park Service design, "Our Park Service Serves Architecture Well," and as an example of excellent government-sponsored architecture in The Federal Presence (1979). [69] The fact that Mitchell/Giurgola was hardly a household name in the early sixties, even in professional circles, speaks eloquently of the building's enthusiastic reception by the popular media. [70]

Alterations to the Visitor

Center

When Ehrman Mitchell re-visited the Wright Brothers Memorial Visitor Center in the mid-1990s, he was astonished by the changes that had taken place since its dedication over thirty years earlier. Mitchell was particularly bothered by the new fenestration, the areas of exterior concrete wall that had been painted white, and metal sheets covering some of the cypress wood panels. The cypress boards at the edge of the entrance terrace were an artistic "identification" that the Park Service chose to fill-in with ordinary plywood to conform to a standard bench. Mitchell was equally disappointed by changes inside the building. Visitors originally entered the lobby to face a wall of windows looking out over the ceremonial terrace to the flight markers beyond. Today, the doors open into a bookshop and an adjacent information desk. Although the wall of windows and set of double doors still form the facing wall, the view is blocked by shelves, postcard displays and Park Service personnel. Visitors are less likely to use the doors to the terrace, which are now practically behind the information desk. The floors, once vinyl tile, are covered with industrial carpeting. As 1960s photographs illustrate, the original lobby and exhibit area flowed together in a single, spacious and airy room. Today, this sense of openness is compromised by the additional furnishings.

The least visible but most extensive alterations to the building involved heating and air conditioning. The air circulation system required improvement almost immediately. Bids were opened for the work in October 1962, and E. K. Wilson and Sons, Inc., awarded the $5,684 contract. Repairs included the installation of two flow meters and "three-way diverting valves in each of three zones to divert hot and chilled water from units coils." [71] In October 1968, further work was performed on the mechanical systems. The existing heat pump and associated piping and an old three hundred-gallon water tank and twenty-five-gallon compression tank were removed and a new hot water boiler installed. The air-conditioning system was also upgraded.

Figure 26. Wright Brothers Visitor Center exhibit area, ca. 1959. (Courtesy MGA Partners, Architects, Philadelphia.) |

The most significant aesthetic alteration of the original design was performed by East Coast Construction Company, Inc., contractors from Florida who were awarded the contract for the refenestration of the building in May 1975. Along with replacing the original glass with safety glass, work included replacing steel window frames with aluminum, replacing steel casement-type ventilation windows with larger, fixed-sash aluminum windows in the assembly room, and altering door dimensions. The most dramatic change in appearance, however, was a matter of color. As 1961-1962 postcards of the building indicate, the original steel window frames and mullions were bright red-orange, a choice that drew attention to the glass areas of the walls and dome. Architect Don Benson recalls that Ann Massey chose the color to add warmth to the building. [72] The color change, increased thickness of mullions, and adjustments in their locations, resulted in marked visual differences. As much as these changes alter the aesthetic of the building, however, they do not compromise its overall form, affect visitor circulation or jeopardize the integrity of the structure. [73]

While the fenestration project was underway, the park considered a much greater change to its visitor center: the addition of an auditorium and museum extension to the north end of the building. In 1977, the MTMA Design Group of Raleigh, North Carolina, produced a full set of construction drawings for the addition. From the front, the building would appear unaltered, but a circular auditorium was attached to the north side of the assembly room and the museum extended beyond the mechanical room. A circular glider display was included within this area, as was a door into the auditorium. The exterior of the addition continued the general pattern of the building's facade, with rope texture concrete areas separated by panels of wood siding and sandblasted textured areas of concrete. On June 26, 1978, the park sent out an invitation for bids on construction of the addition, along with an expansion of the parking lot and related work. Total costs were estimated at between $250,000 and $390,000. The addition was never constructed, apparently due to lack of funds.

During the 1980s, the Park Service installed stair railings on both terraces and a handicapped access ramp alongside the restrooms. There is also a ramp leading up to the ceremonial terrace. At this time, the park partially enclosed the employee parking lot on the northeast side of the building with a wood fence similar in appearance to the fencing along the visitor parking lot. Most recently, in 1997, a new HVAC system was installed, which resulted in the loss of the two windows on the north side of the building. The covered air duct system, which forms a kind of cornice encircling the assembly room, was painted canary yellow. It is certain that the architects would not have chosen to highlight this aspect of the room in such a fashion. [74]

Figure 27. Wright Brothers Visitor Center lobby, now the bookstore, 1999. (Photo by author.) |

Professional photographs of the Wright Brothers Visitor Center tend to exaggerate its modern features by emphasizing the shell roof. With the barren site as a backdrop, all sense of proportion is lost. Drawings are equally deceptive; the plan appears plotted on a relentless grid. Even written descriptions distort the building's image by focusing on its relationship to contemporary airport facilities. In fact, the Wright Brothers Visitor Center is a small, relatively understated building. Despite the elevating concrete platform, it sits low in the landscape, allowing the hilltop monument to take center stage. Wright Brothers satisfies Director Wirth's mandate of protection and use. The building focuses on experience—leading visitors into the building, introducing a few facts, and then pushing them out to the site. The Wright Brothers Visitor Center was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in February 1998.

In 2000, the Park Service faces growing pressure to supplement its natural and historical parks with theater entertainment and computerized, "interactive" interpretation, both for economic reasons and to sustain public interest. Rather than overshadow the Wright's technology with our own, we might learn from Mission 66 museum specialists who worried that their interpretation would distract visitors from the park site and guarded against "overdevelopment of exhibits." [75] The Wright Brothers Visitor Center not only commemorates the achievement visitors come to marvel at, but does so without destroying what remains of the historic scene. The launching of the first flight is easy to imagine from the ceremonial terrace or high atop Kill Devil Hill.

Writing in 1997, Romaldo Giurgola recognized that the Wright Brothers Visitor Center might be considered "thoroughly insufficient" for the Park Service's current needs and visitor load. He also insisted that "the design reflected the particular period of American architecture of the early 1960s in which the rigidity of modernism evolved into more articulated solutions integrating internal and external spaces." [76] If architects and architectural historians celebrate the building's role during this period of transition in the design profession, the visitor center's greater importance lies in its status within the history of Park Service planning. Few buildings speak so eloquently about the goals of the Mission 66 program—the effort to bring the public into the action without damaging park resources, the importance of a modern architectural style representative of new technology, and the need for a functional visitor facility suitable for the next generation.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

allaback/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 26-Apr-2016