|

National Park Service

MISSION 66 VISITOR CENTERS The History of a Building Type |

|

CHAPTER 3

Visitor Center and Cyclorama

Building

Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg,

Pennsylvania

The first three days of July 1863 confederate and union soldiers engaged in the bloodiest conflict ever waged on North American soil, a battle that would ultimately determine the outcome of the Civil War. Almost a hundred years later, the National Park Service attempted to provide adequate visitor facilities at the historic Gettysburg Battlefield. The Mission 66 staff had planned buildings for rugged alpine terrain, barren desert expanses, and spectacular canyon edges; Gettysburg National Military Park presented a greater challenge than even the most forbidding wilderness site. The park's physical remains alone—hundreds of monuments, stone walls, and abandoned farm buildings scattered across the landscape—could not recreate an event of such intangible yet dramatic national value.

It was the Park Service's job to help visitors understand the profound significance of this peaceful Pennsylvania countryside. Conrad Wirth, director of the National Park Service, and his fellow Mission 66 planners approved a location for the new visitor center in the midst of the battlefield, where visitors could view the notable topographical features of the Gettysburg campaign. Situated on a slight rise, the site nestled against Ziegler's Grove took advantage of a panoramic view facing the "High Water Mark" of Pickett's famous charge. The visitor center and cyclorama building would fulfill the Mission 66 mandate of "protection and use," by defining visitor areas and educating the public in battlefield etiquette. Richard J. Neutra, a native of Vienna, seemed surprised when the Park Service awarded his Los Angeles architectural firm the commission for a building on this most sacred site. In preparing his design, the renowned modernist architect and philosopher envisioned what future generations might make of the nineteenth-century legacy. He hoped that "the sad memory of an internal and still painful rift could, by the erection of a monumental building group on a battlefield and through its new dedication, commemorate what mankind must preserve as a common aim of harmony." [1]Like the Mission 66 planners and generations of Americans recovering from the world wars, Neutra viewed the cyclorama project as an opportunity to preserve national heritage.

When Neutra and his partner, Robert Alexander, began work on plans for the visitor center in 1958, major aspects of the design had already been determined. In fact, the history of the visitor center's seemingly modernist form, the concrete rotunda, can be traced back to an unusual type of nineteenth-century painting. French painter Paul Dominique Philippoteaux created several colossal cyclorama paintings in the 1880s, each of which measured the height of a two-story building and required mounting within a cylindrical structure for viewing. The cyclorama placed spectators in the center of a circle and completely surrounded them with the landscape and narrative of another world. The flat painted surface was energized by light, sound and, in some cases, a three-dimensional foreground that included artifacts related to the painted drama. [2] Philippoteaux visited Gettysburg in 1882, and over the next few years he and his assistants completed four versions of the famous battle. The preserved cyclorama, the second in the series, was painted in Paris in 1884. The Congress of Generals and Civil War veterans attended the cyclorama's opening on the twenty-second anniversary of the battle. After display in several locations, the painting was moved to Gettysburg in 1913 and privately owned until its acquisition by the National Park Service in 1941. A tile-covered building on North Cemetery Hill housed the cyclorama, but Superintendent McConaghie planned to move the painting to a better site and eventually to construct a suitable "interpretive center." The prerequisite for the commission was a cylindrical form large enough to contain the 356- by 28-foot canvas. [3]

Like the inspiration for a new cyclorama building, efforts to develop a comprehensive interpretive plan and a central visitor facility preceded the Mission 66 program. During its early years under the jurisdiction of the War Department, the battlefield was without a public museum or on-site exhibits; private guides competed for tourists to lead about the battlefield. [4] The Park Service inherited this system when it took over stewardship of the property in 1933. While the guides provided interpretation, New Deal projects supplied the man-power necessary to build roads and fences, clear land, and plant trees. The CCC helped with basic maintenance and landscaping projects from 1933 to 1942, and Public Works Administration funds covered architectural rehabilitation of selected historic structures classified into fifteen farm groups. In the meantime, the small Park Service staff concentrated on preserving historic properties, acquiring additional land surrounding the battlefield, and discouraging further commercial development in the vicinity. An automobile junk yard, several trash dumps, restaurants, and other modern establishments already compromised the character of the battlefield. [5]

Figure 28. The cyclorama painting was housed in this ceramic tile-covered building on Baltimore Road before it was transferred to the new visitor center. The metal tanks in the background were not part of the Park Service facility. (Courtesy Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.) |

From their crowded rooms on the second floor of the Gettysburg Post Office, park administrators dreamed of a central facility to house the valuable cyclorama, new offices, and services for visitors. Throughout the 1940s, representatives from the regional office wrestled with the choice of a building site appropriate for the painting. Roy E. Appleman, the regional supervisor of historic sites, favored "the site off Hancock Avenue adjacent the Angle," which was "almost exactly on the spot from which the cyclorama was painted." As Appleman argued, "From here the most can be comprehended by the visitor if he is unable to go elsewhere." [6] The Hancock Avenue location was not only perfectly sited for imagining the events of the battle, but also a convenient distance from the National Cemetery and an ideal gathering place for tours. For the next four years, the Park Service would engage in careful planning and debate, weighing the importance of satisfactory visitor facilities against its commitment to protect the battlefield.

Although the Park Service had been actively working to preserve and restore the battlefield since its acquisition, all prospective sites for the new cyclorama complex were located within the park boundaries. Even as he recognized that, "a building of this size is of course an intrusion on any part of the field," Superintendent J. Walter Coleman favored the location on Hancock Avenue closest to Philippoteaux's perspective in the painting. [7] Park Historian Frederick Tilberg attempted to save certain parts of the battlefield and rejected several potential sites, including a location near the Angle that he considered "an objectionable intrusion upon historic ground." And yet, neither Tilberg nor his colleagues saw any contradiction in constructing a modern building on the battlefield they were mandated to preserve. The Ziegler's Grove site offered too many advantages. From this prominent prospect, the building would enjoy a spectacular view of the battlefield, serve as a beacon for visitors coming in from Highway 15, and stand within walking distance of the museum, the National Cemetery, and Meade's Headquarters. A facility amid the battlefield's ruins and monuments could provide unparalleled service to the visiting public. Tilberg wrote up a prospectus describing the benefits of the location, the very spot Mission 66 planners would remember when the new facility finally received adequate funding ten years later. [8]

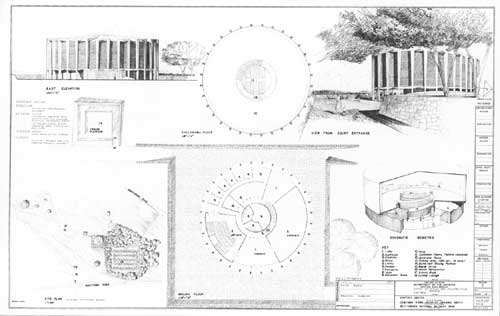

While the wartime debate over the future site waged on, Park Service architects drafted plans for a "cyclorama-museum-administration building" to replace the old facility on the west side of Baltimore Road. Several proposals were completed over the next few months, each siting the building in the "High Water Mark Area" near Ziegler's Grove between Taneytown Road and Hancock Avenue. Five extant preliminary drawings suggest that Park Service architects struggled with the project's programmatic requirements: a vast circular space for the painting, offices, a museum, a lobby, maintenance rooms, and storage areas. All of the proposals chose to house the cyclorama painting in a separate room, but the shape of this space varied. The earliest drawing in this series presents the painting within a cylindrical dome and uses the entrance lobby as a corridor to attach a rectangular administration building. The second scheme houses the cyclorama in an heptagonal building, a form that allowed the administrative spaces to share the interior walls of a more compact facility. Another alternative returns to the cylinder for the painting, but locates administrative facilities in a two-story cubic building directly in front of the main building. At this point, architects appear to have developed composite designs from their preliminary drafts. One shows a dome encircled by a heptagonal observation deck and entered through an exterior administrative wing. The final extant scheme returns to the heptagonal form but groups all administrative functions in a ground floor below the cyclorama.

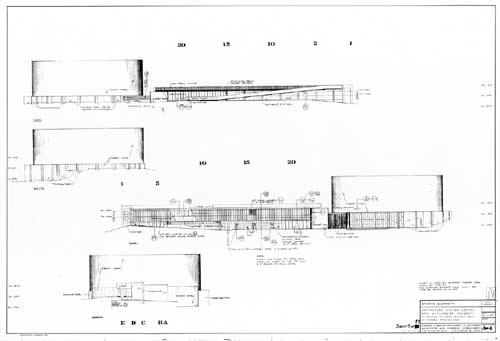

All of these preliminary design proposals show buildings that would have been considered modern. Except for severe strip or rectangular windows, they are without significant ornamentation. [9] Although the cyclorama structures varied in size and architectural style, they shared a similar location. The new facility would stand across the street from the previous cyclorama building and just a few feet from a 75-foot-tall steel observation tower. As the superintendent realized, the Ziegler's Grove site allowed an acceptable replication of the panoramic view depicted in Philippoteaux's masterpiece. When the painting was declared a national historic object by the Acting Secretary of the Interior in 1945, the building project received further incentive. Restoration of the painting by Richard Panzironi and Carlo Ciampaglia, a $10,000 project approved by Congress, was another step towards obtaining an appropriate facility. [10] According to Acting Director Arthur E. Demaray, "as a result of the cleaning and stabilization work, the preservation of the Cyclorama is now assured if funds to erect a modern building to house this important work of art become available reasonably soon." [11] Funding was not immediately forthcoming but, as a "sketch of proposed Cyclorama Building to replace structure on Baltimore Street" illustrates, planning for the museum continued into the 1950s.

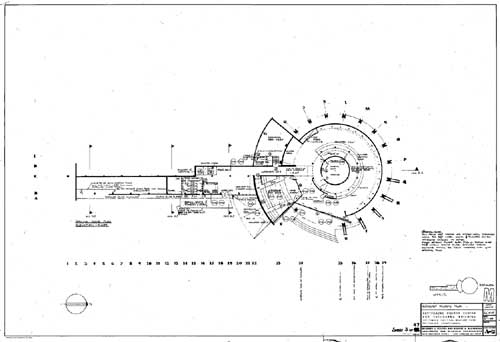

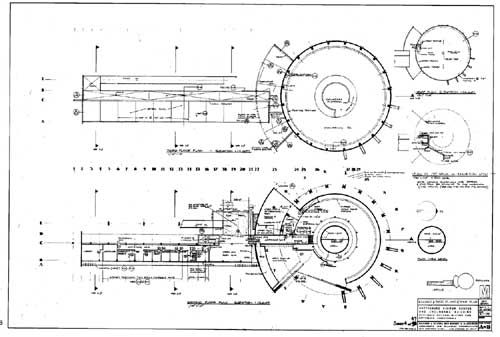

The Mission 66 program enabled the Park Service to produce more detailed plans of the facility it had envisioned at Gettysburg for over a decade. The location of the visitor center was a top priority in the fall of 1956. Edward S. Zimmer, chief of the EODC, visited Gettysburg with Park Service engineer Moran and landscape architects Hanson and Peetz to "discuss location sites for the proposed visitor center" with the superintendent. [12] This "reconnaissance" trip preceded the office's plans for a preliminary visitor center design drafted in February 1957. Located at Cemetery Ridge, south of Ziegler's Grove, the building stood at the edge of the trees between the Meade Statue and Meade's Headquarters. A path led from the parking lot to the cylindrical concrete building. Although the frame was reinforced architectural concrete, the exterior of the cyclorama featured "insulated metal curtain walls and anodized aluminum perforated screen." Concrete ribs tapered down from the roof to the ground, dividing the metal screen into thirty sections. The lower floor offices and visitor facilities were differentiated by "an insulated metal curtain wall and glass." Inside, the first floor was divided into a series of pie-shaped wedges around the central core, the location of restrooms and mechanical spaces. From the lobby, visitors could enter the adjacent auditorium and exhibit rooms or proceed up the ramp wrapping around the central core to view the cyclorama painting on the second floor. A revolving platform took them on a tour of the painted battle scene. Interior walls were to be covered in wood paneling and plaster and the floors in terrazzo and vinyl. The drawings show the visitor center building enclosed within a square paved courtyard surrounded by low stone walls of a random masonry pattern. A path at the far western edge of the site leads to a viewing platform overlooking the battlefield. This square, reinforced concrete structure stands along the path leading from the visitor center to the Meade Statue.

Whether Neutra and Alexander saw the Park Service drawings is unknown, but it was standard practice for the design offices to share such preliminary plans with their contract architects. [13] Perhaps more importantly, Mission 66 planners clearly articulated their general philosophy toward park sites, and such requirements became an essential aspect of the architects' program. The Mission 66 prospectus for Gettysburg was explicit about the "means to an end": the "preservation of the battlefield and its interpretation by more effective and modern means, each tempered with the dignity so necessary in presenting the area as a memorial, will contribute materially to the experience to be gained here." [14] Neutra and Alexander's design for the new visitor center would have to meet the criteria of both a sacred monument and a utilitarian public facility.

Richard J. Neutra and Robert E.

Alexander, Architects and Planning Consultants

Richard Joseph Neutra was born in Vienna in 1892, the youngest child of Samuel Neutra, proprietor of a metal foundry, and Elizabeth Glazer Neutra. From his early youth, Richard seemed to know that his talent lay in the field of architectural design. As a student, he was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright's prairie houses, and during his second year at the Imperial Institute of Technology this interest in American architecture was encouraged by the German modernist Adolf Loos. Although World War I interrupted Neutra's studies and post-graduation plans to join his friend Rudolph Schindler in America, he remained determined to visit the "new world." After several years in the Imperial Army, Neutra found work as a city architect and then in the studio of Erich Mendelsohn, a proponent of the Expressionist strain of modernism. Finally, in 1923, Neutra immigrated to America. After a few months in New York, he moved to Chicago just in time to meet Louis Sullivan. Now impoverished and dying, Sullivan had once inspired the nation with his highly ornamental steel-framed skyscrapers. At Sullivan's funeral, Neutra became acquainted with Sullivan's former student, Frank Lloyd Wright. Over the next year, he spent several months at Taliesin, Wright's Wisconsin home and studio, and he also worked as a draftsman for the Chicago firm of Holabird and Roche. In 1925, Neutra headed to Southern California, bringing with him a background in International Style European modernism and personal impressions of some of the greatest American architects.

During his American travels, Neutra gathered ideas about the country's culture and architecture for two major works—a book called Wie Baut Amerika? (How America Builds) and a utopian project known as Rush City Reformed. The book included illustrations of Wright's concrete houses in Southern California and, like Le Corbusier's famous juxtapositions of ocean liners and buildings, modern architecture adjacent to Pueblo Indian structures. A featured house by Schindler for a Mr. Lloyd in La Jolla resembled the residences Neutra would design for the Park Service in the Painted Desert. But Neutra was clearly most interested in the construction and engineering of Palmer House, a Chicago skyscraper. This mixture of contemporary and historical influences, in combination with his commitment to improving the environment through better design, lay at the core of Neutra's belief in a new architecture. [15] In his idealistic Rush City drawings, some of which illustrated the book, Neutra tried to purify the urban experience by designing his futuristic American city around the automobile, an endless grid of buildings and freeways carefully engineered for high-speed travel. Rush City was a modern metropolis without either the problems of gridlock or responsibility of historic preservation. As biographer Thomas S. Hines has observed, Rush City combined traditional European planning with Chicago School skyscrapers and the Hollywood drive-in. Although Neutra's urban utopia was never intended to be built, aspects of the project appeared in his subsequent designs for schools, community buildings, and urban planning projects. If he contradicted the rigid organization of Rush City in later work, many of Neutra's ideas about social life can be traced to this early project.

Neutra quickly made his reputation in the rapidly growing city of Los Angeles, an ideal place for experimentation. Here, he found clients eager to live in houses without nostalgic or historical associations. The residence Neutra designed in 1927 for physician Philip Lovell, a "naturopath" who practiced medicine without drugs and advocated vegetarianism, and his wife Leah, the co-director of a liberal kindergarten, became known as the Health House. It was an architectural representation of Southern California's athletic lifestyle and a perfect advertisement for Neutra's new architectural practice. Public interest in this extraordinary building was so intense that when Dr. Lovell invited those who were interested to tour the house, fifteen thousand people accepted the invitation. [16] Neutra soon became famous for energetic buildings that brought sunlight and sea air into the living space. During the thirties and forties, he designed dozens of houses, schools and public buildings along the coast of California. His progressive aesthetics, and the openness and vitality of his modern designs, were especially welcome in this untested environment. Neutra's experimental school in Los Angeles, "designed for activity rather than simply for listening," promoted a freedom in school planning that has since become standard practice. [17] Along with fellow Viennese architect Rudolph Schindler and many disciples, Neutra designed the modern architecture that is now considered traditional in Southern California. No history of American architecture fails to mention his importance.

It must have been a surprise to many when Richard Neutra, the renowned modern architect, decided to share his work with a partner. During his first years in Los Angeles, he had briefly collaborated with Schindler, but the two didn't work well together and dissolved the professional relationship. Nearly thirty years later, Neutra was himself an icon of modern architecture whose achievements reflected a forceful personality, original architectural philosophy, and iconoclastic design concepts. With his wild white hair and piercing eyes, he appeared a stereotype of the egotistical genius. And yet, in his later years, Neutra's practice had begun to diminish. Rather than retire with a spectacular resume of accomplishments, however, he hoped to revive his career by collaborating on larger urban projects. When Robert Alexander approached him with hopes of working together on a major Los Angeles housing development, Neutra accepted the challenge.

Robert Evans Alexander was born in 1907 in Bayonne, New Jersey, and played football for Cornell University. After graduating in 1930, Alexander moved to Southern California, where he became a partner in the firm of Wilson, Merrill and Alexander. The firm gained professional notice during its collaboration with Reginald Johnson and Clarence Stein on Baldwin Hills Village beginning in 1937. This 627-unit residential development launched Alexander into the world of urban planning. In 1948, he became president of the Los Angeles Planning Board, a position that proved helpful in obtaining coveted work from the Federal Housing Authority (FHA). Alexander hoped to design one of the FHA's most prominent projects in Los Angeles—the Chavez Ravine housing—but needed the clout of a major architect to secure the commission. Neutra fit that description, and in 1949, he agreed to work with Alexander on the Ravine project. Although this controversial development was never built, the architects' collaborative experience resulted in the establishment of Neutra and Alexander. [18]

In Robert Alexander, Neutra hoped to find a colleague who could bring in larger commissions and oversee their administration. During its early years, the newly established firm obtained several major contracts, including an urban redevelopment project on the island of Guam, college buildings, churches, and elementary schools. However, even as Neutra and Alexander received design awards and a steady stream of clients, their personal working relationship had begun to crumble. The fact that Neutra and Alexander worked in separate offices did not contribute to a smooth collaboration. Neutra concentrated on the design concepts from his home in Silverlake, while Alexander tackled the firm's planning issues from an office down the block. The partnership began to dissolve during the Gettysburg and Petrified Forest commissions of 1958, with the understanding that work already begun would be followed to completion. During the final stages of these projects, Neutra continued to work from Silverlake, while Alexander opened his own Los Angeles office on South Flower Street.

As the partnership developed, Neutra and Alexander's conflicting design philosophies became increasingly apparent. Neutra produced austere buildings based on the precepts of International Style modernism, whereas Alexander tried to soften the crisp lines and severe minimalism. Given Neutra's rigid modernist aesthetics, it must have been frustrating for Alexander to hear the philosophical rationalizations of his work. In his writings, Neutra drew on regional history, natural surroundings, and personal experience to discover universal principles, which he then attempted to represent in built form. Like other modern architects, he describes historical allusions in his work that are sometimes difficult to perceive. In a letter to Regional Director Thomas Allen he noted that "although our building consists of rolled steel sections and aluminum sash plate glazed and fabricated as of today, we have, in other aspects in our motivations of design, followed the desire to relate men's work of today with the long historical past." [19] Unlike some of his colleagues, Neutra realized that historical associations were often overwhelmed by the modernist style, and he attempted to compensate through his writings.

When Arts and Architecture profiled famous west coast architects in 1964, Neutra was in his seventies and had finally completed his work for the Park Service. The article portrayed Neutra not as a regional designer or a relic of the International Style, but as an architect whose significant contributions to the profession had continued to evolve since the 1920s and 1930s. If most famous for the unusual construction and philosophical ramifications of his Lovell House, Neutra had also developed the "bilaterally illuminated classroom lighted by strip window on one side and sliding glass doors on the other." In urban planning, he was responsible for city projects integrating "below grade speedways; underground parking garages; parks separating traffic and high-rise apartments; pedestrian walks about street level; buildings with ground floors open to traffic; and small neighborhood plazas." During the war years, Neutra transformed traditional materials, such as wood, brick, and glass, into innovative panels, sleek surfaces, and walls that seemed to dissolve into the landscape. Perhaps most important in understanding Neutra's contribution to the architectural profession and the attraction of Mission 66 planners to his work is the incredible consistency of his design. Because he believed that design choices developed out of human needs, he produced a fairly standard set of solutions to social problems. As the journal article pointed out, this system resulted in efficient and accurate estimates for contracting costs. Neutra's faith in the "social significance" of his architecture, his effort to create a balanced, "harmonic" relationship with the environment, and his experience with modern materials in public buildings might well have been criteria for a Mission 66 job description. Working with such an artistic personality could pose risks, but with Neutra one knew just the type of building to expect. The Park Service could be conservative in its choice of "radical" architects. [20]

Designing the Visitor Center

and Cyclorama Building

A few years after receiving the commission for the visitor center and cyclorama building, Richard Neutra recalled his initial thoughts about the future "shrine of the American nation." Like Mission 66 planners, Neutra believed modern architecture could fade into the landscape, leaving the park to display its historical legacy without interference. "Our building should play itself into the background, behind a pool reflecting the everlasting sky over all of us—and it will not shout out any novelty or datedness." [21] Modernism was bolstered by the theory that advanced materials and sophisticated technology would satisfy basic human needs, leaving nature and history undisturbed. Modern architecture attempted to "play itself into the background," not with a rustic disguise, but by minimizing the excess of such contrived designs. Shorn of all ornament and without the distraction of gingerbread or peeled logs, modern buildings pretended to be nothing but functional spaces, the very simplicity of which became their aesthetic. If the modern style broke with the Park Service's architectural tradition, the theory behind modern architecture mirrored the goals of the Mission 66 program. In retrospect, modernism could hardly live up to all of these lofty aspirations, but in the 1950s, Americans still expected an architecture transformed by technology. Throughout his many books and essays, Neutra expressed faith in the power of good design to "see organic evolution continued" and "check the technical advance in constructed environment." [22] Neutra's theories about the relationship between people and their surroundings may have made his work particularly attractive to Park Service planners.

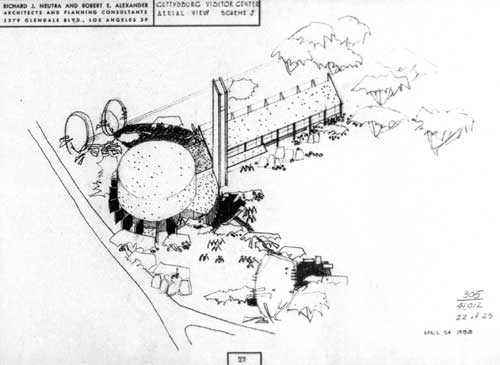

In his memoirs of the Gettysburg commission published before the building's dedication, Neutra recalls receiving a phone call from Washington while traveling through the Arizona desert. He spoke with Secretary of the Interior Fred Seaton and Director Conrad Wirth about the building, and later personal meetings helped him to develop a design. The firm of Neutra and Alexander produced a set of preliminary drawings for the visitor center and cyclorama dated April 28, 1958. A "master plan development" drawing completed by the Park Service just the week before shows the footprint of the building oriented as the partners planned, with the rotunda end facing the High Water Mark. The general site layout also showed a road from the parking lot to Meade's Headquarters, the existing observation tower on the edge of Ziegler's Grove, and a portion of the National Museum to the north of Hancock Avenue. [23]

Figure 30. This preliminary drawing for the visitor center was part of a set of twenty-three sketches completed by Neutra and Alexander in April 1958. Note the nine-story observation tower and the orientation of the building. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

In their first set of drawings for the visitor center and cyclorama, which included some sheets labeled "scheme J" and some "scheme K," Neutra and Alexander imagined a building similar in structure to that actually built, but significantly different in terms of visitor experience. The visitor center was located on the site indicated by the slightly earlier Park Service drawing: the rotunda just feet away from Meade Avenue and the space reserved for "gatherings" parallel to the road but sheltered by a stone barrier. The first scheme placed the office wing nearest the parking lot so that approaching visitors could enter the roof deck viewing area immediately or proceed to the main entrance. The outdoor promenade continued around the rotunda. Visitors could take an elevator up a slim nine-story tower located between the office wing and cyclorama. A pool was planned at the transition of the horizontal and cylindrical building forms. Circulation diagrams emphasized the visitors' approach from the parking lot to the entrance, as well as around, inside, and outside the building; the battlefield could be studied on different levels and from multiple perspectives. The set of plans also included a list of museum exhibitions, labeled and numbered from one to twenty-three.

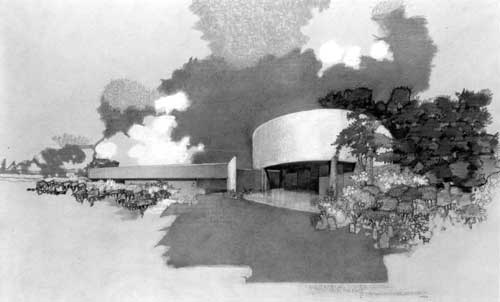

Although the firm's general idea gained approval, the Park Service preferred a less conspicuous version of the design. The partners worked on revising drawings over the next year, finally submitting a second set dated June 1, 1959. [24] In an effort to minimize the rotunda, the building plan was flipped so that the cylinder was partially sheltered by the grove of trees. The viewing tower and rooftop promenade around the rotunda were removed from the program. In the revised design, the viewing deck offered a clear vista of the battlefield, but the entrance to the deck was no longer so obvious. The architects attempted to improve the ramp situation by adding a system of reflecting pools, one of which paralleled the viewing deck. According to project architect Dion Neutra (Richard Neutra's son), this was an effort to "entice people to disperse themselves along the length of the building to view the battlefield" and thereby avoid "the crush at the top of the ramp." [25]

Throughout this revision, the firm envisioned the contrast between the building's modern materials—steel, glass, aluminum, and concrete—and the random masonry walls and panels built of local stone. In the design of their courtyard stone wall at the Painted Desert Community, the architects looked to ancient desert dwellings for inspiration. At Gettysburg they also attempted to integrate regional building traditions and planned to find a suitable example of local masonry in a nearby historic building. During the next two years of construction, the architects became obsessed with perfecting the stone walls based on the selected historic prototypes. This relatively minor aspect of the finished building represented something more to the architects. It was both a departure from Neutra's earlier work and, perhaps, a concession to the unique park site.

The specifications for the revised visitor center included a "personal word to the bidder" intended to encourage good faith and open communication throughout the construction process. The firm anticipated that contractors might find certain unfamiliar practices in need of clarification. In an addendum to the specifications produced about three months later, Neutra and Alexander described an extra artistic flourish: the addition of a final spray coat of glitter finish applied directly to the wet cement with a "specifically designed spray gun." The glitter was small flakes of "diamond dust" (mica) applied to the white areas of cement at a concentration of four to five pounds for each hundred square yards of surface. The addendum also included explicit instructions for the design of the ribbed concrete and the elimination of any form marks that might interfere with the vertical pattern. For the next three years, the contractors and architects would struggle with these requirements. Along with the technical specifications, the firm developed a more artistic presentation of the building for the client. Neutra created a pastel rendering of the building from the Hancock Avenue approach; the white form accented in turquoise and purple was surrounded by green grass and a forested background. [26] The architects also produced a brochure with studies of the cyclorama building, a copy of which was sent to Superintendent Myers. [27]

Figure 34. "Gettysburg Visitor Center, view from the east," pastel by Richard Neutra, 1959. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

Since the project's early planning stages, Mission 66 planners had anticipated many benefits from their new visitor center and cyclorama, but they also worried about the impact of growing numbers of tourists and businesses attracted to the area. The 1960 Master Plan articulates some of the park's concerns about modernization, pointing out that "Gettysburg's popularity has meant increasing commercial and housing development which, even now, is destroying its attractive rural character and detracting from the Park itself." [28] Although complaining bitterly about private enterprise and the excesses of "commercialization," the Park Service was enthusiastic about its own modern roads and visitor facilities. If these were intrusions on hallowed ground, the benefit of necessary improvements would far outweigh any damage. The new visitor center would serve as the "initial point of contact and orientation," a role facilitated by its location at the juncture of six highways. Visitors could "refresh their memories on the stories of the battle and the Gettysburg address, obtain literature, and, if they wish, the services of a battlefield guide who is licensed and supervised by the Superintendent of the Park. Here they may also view the impressive Gettysburg Cyclorama which depicts a moment in the climax of Pickett's Charge and should inspire them to accept the Park's invitation to take its walking tour to the scene of the charge itself." [29] This site had the distinct advantage of permitting the study of the battlefield from its observation deck, surrounding paths, and walking tour. Mission 66 planners understood that, while park staff and Civil War enthusiasts might best imagine the events of the battle unfolding on a site free of modern intrusions, the average visitor looking out over the site saw ordinary fields dotted with curious statues. The purpose of Mission 66 was to benefit millions of anticipated visitors, and to this end the visitor center would bring life to the historic landscape.

Building the Visitor

Center

In mid-August 1959, the EODC was in midst of reviewing the plans, and bidding on the visitor center and cyclorama building opened September 29. The contract was awarded to the Orndorff Construction Company, Inc., of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, for its bid of $687,349, an estimate $45,000 less than the second lowest proposal. [30] Total construction time for "one of the largest buildings in the way of Visitor Centers to date" was projected as a single year; it was Director Wirth's particular hope that the building could be dedicated while President Eisenhower remained in office. [31] The project's four primary contractors officially began work on November 18, though the electrical, cooling and heating, and metal workers awaited Orndorff's preparation. [32] Within a few days, the construction company had a tractor trailer at the site and inspectors checking elevation lines established by EODC Engineer Westerfield. According to the contract specifications for the visitor center, the rotunda was to be prepared for installation of the cyclorama painting within just one hundred and eighty days. To meet this tight deadline, the contractors were advised to give priority to the construction of the concrete drum. [33] After excavating a footprint 130 feet in diameter and digging spread footings, contractors began driving piles for the rotunda foundation. They were surprised to find that the rock did not meet required standards; in fact, it didn't appear to be the same material obtained by prior tests. Upon further investigation, the contractors discovered the building had been moved about twenty feet since the initial foundation inspection. During their December 17 site visit, the architects hired an expert to analyze the situation. Robert J. Stickel, a civil engineer from Camp Hill, Pennsylvania, suggested shifting the building an additional twenty feet to the east. [34] Throughout these inspections, the construction company insisted it could "do nothing until the center pivot point was established by the survey crew." [35] By January 1960, Neutra and Alexander had revised the foundation plan. Over the next month, the remaining footings were custom designed to suit their varying site conditions.

In early December, Neutra and Alexander congratulated the Orndorff Company for recognizing the "national importance" of the future building. [36] The architects had received the contract to supervise construction of their design, and it was in their best interest to anticipate mutual cooperation in the work ahead. [37] Over the next few years, both principals of the firm would visit the site many times and respond to everyday questions by mail and telephone. Dion Neutra remained based in Los Angeles, but represented the firm in official correspondence and on many site visits. [38] Weekly supervision of construction was undertaken by one of Richard Neutra's former assistants, Thaddeus Longstreth, who had since opened a private architectural practice in Princeton, New Jersey. As the firm's "eastern representative," Longstreth maintained a weekly record of construction progress, logging nearly one hundred supervisory reports between November 1959 and March 1962. He focused on "the interpretation of the plans and specifications from an architectural and aesthetic viewpoint rather than the mechanical aspects of the building." [39] Technical matters were the prerogative of subcontractors in California, including mechanical engineer Boris M. Lemos, electrical engineers Earl Holmberg and Associates, and the firm of Parker, Zehnder and Associates, consulting structural engineers. In addition, the project was under scrutiny by David O. Smith, the project supervisor. Although a Park Service employee, Smith acted as a liaison between the government and the architectural firm. The highest authority in the Park Service with intimate knowledge of the project was John B. Cabot, supervising architect of the EODC in Philadelphia, but even Cabot declared Gettysburg Superintendent James B. Myers the official "owner" or client. Along with these overseers, the crowd at the construction site included Willard Verbitsky, a 340-pound superintendent known as "Little Willie" by his co-workers at Orndorff Construction. Both John J. Bordner, vice president of Orndorff, and President Brickley S. Orndorff stopped by to check on progress and handled the project's substantial correspondence with its west coast designers. The construction company hosted an introductory dinner for the group on December 17, 1959, a few weeks after work had officially begun.

While the foundations were under scrutiny, the architects turned their attention to sample panels of the stone walls. Although the requirements for the stone masonry may have appeared stringent, the contractors had been forewarned by the building specifications, which stipulated every detail—from the three sample panels to the provision of a local example for the mason's examination. [40] The stone required in the specifications was native "'Arcure' Pennsylvania Sandstone in the tan, brown or buff color range." As the architects explained, the most aesthetically pleasing masonry pattern consisted of "darker and larger stones . . . nearer the bottom of the piers and color and size graduating toward the top to lighter and smaller pieces." [41] They also indicated that the sides of the piers as seen from the east were most important and that the very best stone should be reserved for the four piers nearest the entrance. [42] In preparing the sample, Longstreth and the contractors explored the surrounding area for historic examples of the desired "random rubble ashlar pattern with more irregular, triangular shapes." [43] The Vickery Stone Company of Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, dumped approximately 155 tons of Blue Mountain split-face Pennsylvania sandstone at the job site on February 25, 1960. The architects hoped to have the panel erected by December so that it could weather over the winter. [44]

Despite efforts to get off to a friendly start, the foundation problems inspired more doubts than confidence. When construction was still in its infancy, the architects warned Orndorff not to substitute less expensive or more accessible products for those specified in the contract. Neutra and Alexander insisted they could "not accept very much deviation for design reasons." [45] The firm's adamant adherence to specifications became a problem for the contractor because high-quality products were difficult to obtain; both parties disagreed on what they considered suitable substitutes for specified items, and such commitment to high standards resulted in countless delays. For example, the architects selected expensive Japanese tile distributed by a Los Angeles dealer to cover the inside of the cyclorama ramp. [46] This decision not only resulted in considerable delays, but evoked disapproval from those committed to the Buy American Act. The fact that the architects supervised construction undoubtedly helped the contractors understand the complex project, but it also allowed the design process to extend into the construction phase; the designers could not resist enhancing the building's aesthetics whenever possible. Rather than simply directing installation of the original tile, the firm continued to imagine new effects, envisioning "a mixture of two closely related shades of dark brown or black, perhaps alternating vertical strips to give a very subtle corduroy-like effect as a backdrop for the stainless tubes" and with a matte glaze to prevent any "glitter." [47] Regardless of additional time or expense, the architects based decisions on aesthetic issues and structural considerations that might effect the performance of the building. While such practice resulted in exceptional quality, the contractors and subcontractors were sometimes baffled by what they interpreted as capricious decisions.

When the spring building season began in early March 1960, the foundations were in place, and the architects focused their attention on concrete forms. Once the outer form work for the rotunda was finished, pouring began. The first pour was completed in sections between columns. The contractors worked their way around the circle, leaving space for the auditorium doors, and then moved on to the next vertical wall segment. Scaffolding was erected to hold workers and concrete in place as the layers of lifts accumulated. The rotunda's inner form was begun in August, and as construction progressed, it advanced in height along with the exterior. Photographs of the unfinished concrete shell in September show a fortress equally as impressive as the final product. The remaining wood scaffolding, with its tiny ladders still climbing up the side of the building in December, gives a sense of the incomplete rotunda's huge scale; in contrast, the finished form would ultimately succeed in dissolving into the grove, at least as much as could be expected from such a massive shape. The cylinder was of ribbed concrete, a decorative vertical pattern that required precise formation.

In the same way that Neutra and Alexander insisted on perfecting the rough and random look of the stone masonry, the architects were determined to achieve a "crisp and clean" contrast in the concrete. The aesthetics of both interior and exterior could suffer from shoddy form work, careless concrete preparation, or improper pouring. Although Park Service project supervisor David Smith warned against using prefabricated plywood panels, the contractors objected to the expensive 1- by 6-foot shiplap required in the specifications. [48] In a letter to Orndorff, Dion Neutra explained why seemingly insignificant details of the concrete process were aesthetically important and mentioned similar techniques used by other architects, such as the "Unesco Building in Paris and any recent work by Le Corbusier," to illustrate his point. [49] Such modernist buildings used concrete to create "pure" forms without any suggestion of their fabrication. The capacity of concrete to take on a smooth, sleek appearance in a variety of shapes was the very reason it became a featured material of modern architecture. The cyclorama ramps under construction might prove expensive and challenging to design properly, but they would also contribute to the building's streamlined aesthetics. Chamfer strips were removed from exposed corners because they made "the building look clumsy and warehousey rather than sharp and crisp." [50] According to Dion Neutra, such attention to detail was "why the Park Service went west for their architect, and why this will be a distinguished building with all of us working on it, dedicated to this proposition." [51] The firm finally compromised by allowing plywood forms in unexposed areas, such as the inside curved surface of the mechanical room and the portion of the rotunda hidden by the painting. Some covered areas, the outside surface of the central drum in particular, required shiplap to produce "a true curve." Although the firm anticipated a certain amount of rubbing out of form lines, they preferred to "have as little patching or rubbing as possible, but rely rather on the best form work to avoid problems." [52]

As Neutra and Alexander and contractors debated the importance of proper form preparation, they also confronted deficiencies in structural concrete. The concrete columns in the main rotunda, alphabetized from F to Z, each required proper footings and piers. Park Service supervisor David Smith reported on defective concrete in the main R column that extended from the foundation to the support of the cyclorama drum; Longstreth's construction report described the problem as "stone pockets" that compromised the density of material. [53] The architects immediately demanded the removal and replacement of the column. They were alarmed "to think that these results are being obtained on a building that will depend in such large measure on the quality of its concrete finish." [54] Later that month, the adjacent T and S columns were discovered to be equally faulty and also required removal. [55] Upon further inspection, it was determined that the "honey-combing and stone pockets" resulted from the failure to adequately vibrate the concrete. Soon after, Smith reported "errors" in the footings and asked for suggestions. Toward the end of April 1960, he agreed to make a surprise visit to the concrete mixing plant to take test samples of sand and aggregate. [56] In the meantime, Brickley Orndorff promised to write the company with his complaints. Flawed concrete preparation, usually a result of improper vibration, plagued contractors and architects alike for the duration of the project.

Despite the construction problems, "the Lincoln Memorial at Gettysburg" was included in a profile of the firm by Pacific Architect and Builder in May 1960. An aerial view of the building from the entrance facade, rendered in pastels or watercolor, showed the three reflecting pools darkened and the rotunda dwarfed by surrounding trees. The short description of the building noted that it was under construction "on the famed battlefield some 200 yards from where President Lincoln made his speech," and stood "only a stone's throw from the horrifying spot where the contest found its climax." The location of the building was clearly considered an admirable quality. [57]

The architects returned to the aesthetics of the stone masonry piers and walls in mid-April 1960, when a sub-contractor began work on a second sample panel. During construction Longstreth deemed the panel too similar to the initial rejected attempt. The frustrated mason described his previous success erecting stone walls for the National Park Service at Camp Green Top (Catoctin Mountain Park) in Thurmont, Maryland. Longstreth visited the park, only to find that the walls in question were "too polychrome in range with a preponderance of square shaped pieces." [58] After Cabot and Neutra inspected the work the next month, they accompanied contractors to an old barn on Route 116 west of Gettysburg. A corner of the structure exhibiting the desired variety of stones and mortar thickness became the example for visitor center masonry. [59] On June 21, Longstreth and Bordner traveled to the Blue Mountain Stone Quarry ten miles northwest of Harrisburg in search of stone that might cut into satisfactory shapes. They discovered two potentially useful types of stone—one with a "regular" effect when cut and the other likely to form "larger irregular shapes" but too gray in color. [60] The quarry owners were so sure of success that they volunteered to construct a product sample for the architects' approval. Longstreth and Smith then accompanied them to the exemplary barn to see the desired stone pattern. The next week, the quarry owners erected the sample from stone on the site supplemented with their own Blue Mountain stone. Longstreth reported that this panel "showed great improvement over previous efforts, having more irregular shapes, thinner dry-wall appearing joints, larger and darker stones at the base." [61] Nevertheless, he felt that the nature of the rock still hampered efforts and further construction would require constant supervision. He hoped that the principles learned while building the samples could be transferred to the field, allowing the masonry covering the sides of the rotunda's external concrete piers to become "fieldstone panels." The five piers nearest the main entrance extended beyond the edge of the rotunda and created a platform for the concrete cylinder.

Once the mason had actually erected part of pier R and column P, Longstreth commented on the lack of color variation; tones were supposed to graduate from dark on the bottom to lighter nearer the top. He also demanded thicker, darker stone for the panels, noting that the thinner stone might be reserved for the center of the walls. The stones were to appear naturally chunky and randomly selected, but the wall itself required proper alignment. In terms of pattern, Longstreth asked the mason to avoid "uphill joints" or stones laid too vertically. The mason was to begin with the least visible piers, such as the north side of pier Q, before moving on to the featured south facade. [62] During supervision of the pier work in early November, Longstreth warned the mason of "downhill joints," and suggested that he constantly stand back from his work to avoid such monotonous effects. Although larger and wider stones were now in use, the color range was still disappointingly small and the joints too horizontal. Given the range of colored stone provided and its varying appearance when split, Longstreth felt that only constant effort would achieve the desired results. [63] By this time, John Cabot had given Longstreth full authority over this aspect of the project. [64]

Figure 35. Stone panel and stone wall on the south end of the office wing, 1962. (Photo by Lawrence S. Williams, Inc.) |

In the fall of 1960, as work began on the interior surfaces of the building, aesthetics took precedence once again. When Orndorff submitted vinyl wall covering for the office partitions, the architects were horrified by samples that "might do in a bar or club, but not in this type of structure." [65] They also disapproved of the wood sample panels, noting "the dust and pock marks, as well as the too-glossy finish," a result far different from the sought after "satin, even, low sheen, full bodied, rubbed effect." As for the colored concrete required in the exterior ramp, the architects preferred the chocolate color supplemented with abrasive additives for additional texture. Orndorff sent three samples sealed differently but all including sidewalk grain chips, and not very tactfully indicated that the architects had now received "the full range of the colors as manufactured by A. C. Horn." [66] The next week, the architects reported the lack of any attempt to use silicon carbide (alundum grains) to create the specified textured surface. [67] To complicate matters, the exterior ramp required extensive structural revisions. While the architects complained about the contractor's interior selections and form work, the Park Service blamed the architects for a five-month delay in submitting a finish schedule. [68] Even as they exchanged complaints, however, all parties pressed on. Orndorff scheduled terrazzo work in December, beginning with the ground floor lobby and restrooms, continuing to the second floor office wing and then entering the cyclorama. [69]

Figure 36. Gettysburg Visitor Center and Cyclorama, view of the roof structure under construction, December 1960. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

During the slow and difficult interior design phase, work on the cyclorama roof proceeded quickly and relatively harmoniously. In a September 1960 report to the architects, Parker, Zehnder and Associates explained details of the construction joints for the cyclorama beam, wall, and floor. The appearance of the concrete forms changed significantly in October, when contractors began to erect steel girders and beams for the rotunda roof. Two cranes were required, one to place the cyclorama roof steel and another to lift the concrete for the interior columns. Project Supervisor Smith updated the architects on conditions at the site and described his view of future progress:

As it stands now, the center post is solidly supported 2' above the final elevation and 6 girders from J clockwise . . . inclusive are attached. After the cyclorama wall is completed, the other four beams and purlins will be erected and the cables connected. I assume at this time the blocking will be removed (although I see no provision such as wedges to do this) letting the center post settle to its final elevation. I assume this is the correct point in the installation for the welding of the beams to the center post. [70]

Neutra visited the site around Christmastime specifically to photograph the interesting spiderweb pattern created by the rotunda's exposed steel framing and endured "great pains and great physical discomfort" in the process. [71] According to Smith, the revealed roof structure had already attracted much attention. The Bethlehem Steel Company took pictures of the cyclorama drum and roof structure for a full-page advertisement and brochure publicizing its bridge cables. The rotunda roof was built around an 18-foot center column suspended with steel purlins radiating outward above a system of "prestretched and proofloaded bethanized bridge strand." [72] The bridge cables were attached to the base of the central column and to the upper perimeter of the cylinder, forming a flexible "web" of fibers. After the erection of the steel but before installation of the gypsum roof, the cables were adjusted to vertically align the central column. The framework of purlins and girders above resembled a wagon wheel. One of the photographs in Neutra's Buildings and Projects shows two men near the central "trunk" dwarfed by the steel umbrella overhead. Views were also taken from above the cyclorama, probably from one of the cranes used in the construction process. It was a dramatic photo opportunity and one that would soon disappear under layers of lath and plaster. By the following summer, the roof scuppers had already become filled with leaves, and Smith planned a regular inspection schedule to keep the drains clear. [73]

The firm's specifications emphasized their quest for "Architectural Effect," a subjective standard they strove to achieve through materials, methods, and even decorative art. Bush-hammered columns formed an important part of the original interior scheme, and as the project progressed, this rough appearance became increasingly desirable. While contemplating the color scheme, the architects decided to leave all bush-hammered columns in their natural state to expose the black aggregate and reduce the quantity of dark brown. [74] After the bush-hammering process, columns required additional work to "remove the spiral form marks and to give surface variation as called for in specifications." [75] In February 1961 all parties agreed that bush-hammered columns should be left natural on both the interior and the exterior. And by the next month, the preference for bush hammering included the bench surrounding the museum exhibits. The Park Service issued a change order to reveal the aggregate in the circular museum bench, "upon consideration of the color scheme for the building, and after seeing the effective result of the exposed aggregate in bush-hammered surfaces at various locations in the building." [76] The architects also improved the transition from the second floor corridor to the cyclorama ramp by substituting stainless steel for galvanized iron in the bridge spanning the exhibit area. Since the ramp was enclosed within a stainless steel cage of the same material and style as the rostrum, this choice unified the metal work in the museum. The transition plate was actually thin strips of steel with enough space between to create a dizzying effect when looking down at the terrazzo floor below. The plate and corresponding balustrade also provided support for a glass mural.

Just as they imagined the "floating" office wing, the architects conceived of a dramatic interior with office partitions "shooting on into the corridor and the feeling of the long vista of the windows continuing beyond." [77] Demountable partitions of the "flush movable type" produced by the Neslo Manufacturing Company in New York separated the office space in the second floor administrative wing. This system allowed removal of any panel in any order without affecting other partition walls. The individual laminated vinyl panels could be taken apart and rebuilt if necessary.

Figure 37. View looking south into the second floor lobby space, with offices beyond. The ramp up to the battlefield overlook is visible outside, 1962. (Photo by Lawrence S. Williams, Inc.) |

By mid-summer, architects and contractors prepared for work on the building's unusual solar window shade system. The entire east office window wall was covered by exterior louvers, which created a pattern of vertical lines that changed in width as the shades were manually cranked open or closed. The louvers were fabricated of ALCOA aluminum covered with a Lemlar primer and two coats of baked enamel finish. As Dion Neutra explained to the EODC, his father was "recognized as perhaps the originator of this type of solar control, having first used it some twenty years ago, when every piece had to be custom made." In 1956, the firm's Northwestern Mutual Fire Insurance Office (1951) was included in a book about innovations in aluminum construction. [78] This building is dominated by vertical aluminum louvers that extend from the 7-foot office windows beyond the spandrel below, producing a unified front facade. As Neutra reported, the architects had used the same design in more recent local projects with excellent results. He may have been thinking of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Building (1956) near Wiltshire Boulevard or current work on the Los Angeles County Hall of Records, which featured "base-to-cornice light controlling, energy-conserving louvers" constructed about the same time as the visitor center. [79] In addition to the streamlined vertical lines of the louver pieces, the architects appreciated their transparency, which gave a contrasting sense of lightness to the surrounding concrete.

During construction, the architects decided to change from the manual louver controls to the Lemlar Manufacturing Company's system of automatic solar adjustments. The park hesitated to spend the extra money necessary for this luxury, but the architects were persuasive. According to Neutra, there were practical reasons for mechanizing the louvers. People tended not to adjust them until they were very uncomfortable and, once closed, they would usually remain shut since artificial lighting was provided. This "greater dependence on automation and push-button living" increased as the world modernized. Dion Neutra sent the park a letter from the manufacturing company stating that the cost of operating the louvers automatically would be less than the expense of hiring someone to turn the hand crank throughout the day. Lemlar suggested that curious park administrators inquire about the louvers at a milk company in Camden, New Jersey, where they had been installed in 1957. [80] After some delay due to travel engagements, John Cabot resolved the situation by explaining the Park Service's hesitancy to install "mechanical gadgetry." Nevertheless, Cabot was willing to approve the louvers, if provided with a hand crank for emergencies and the chance to review additional costs. The company's promise to install the mechanism itself sealed the deal. [81 ] The Lemlar Manufacturing Company sent their sun louvers to the site April 27, 1961.

The cyclorama's motorized doors could become an equally dynamic aspect of the main entrance facade, but they were only intended for use on special occasions. A portion of the east rotunda was outfitted with mechanical sliding doors, and a wall of the auditorium operated on a pivot. When both doors were opened, the museum became a speaker's platform and the south lawn an expansive seating area. The architects chose the Ferguson Door Company of Los Angeles to manufacture the motorized sliding and swing doors. After reviewing the Ferguson Company's installation and drawings, the architects were pleased with the workmanship of a complicated, technical project. They looked forward to the "spectacle" of watching "the doors all operating at once." [82] The next spring, project supervisor Smith reported that the "pattern sheets" for the Ferguson doors were undergoing a final adonizing test. The architects advised waiting to install the door panels until after all sandblasting, Thoroseal application, and plastering had been completed. [83] Finally, in early August, only a delay in the arrival of the doors prevented the Park Service from hanging the painting." [84]

If the louvers and walls only operated at certain times, the building's water features provided a constant source of stimulation. A few months earlier, the concrete had been poured for the upper pool on the office wing roof. This stretch of water extended the full length of the viewing deck before flowing down to an intermediary pool on the auditorium roof and cascading to a ground level pool near the visitor center entrance. The water was kept in motion by a "piped circulation system." According to the specifications, after the completion of concrete work, a "waterfall diverter" was required in the intermediate pool to "reduce splash, impact, and noise to a minimum, as audited from the Projection Room." [85] Pouring the concrete for the pools was a relatively straightforward process, but waterproofing them proved more challenging. By June 1961, a special polysulphide caulking compound was required in the pool joints to prevent water from leaking into the office wing below. [86] A few months later, the park "noticed that the concrete slab, placed over the roofing to provide a surface for the view deck, had moved thereby sheering the deck drains, pulling the cove base away from its backing and presumably rupturing the waterproofing." Besides the pool repairs, the adjacent view deck required a quarry-tile walking surface. [87]

Figure 38. When the glass doors were opened, this section of the Cyclorama building's drum served as a stage complete with rostrum. The auditorium doors opened to provide indoor seating, and the lawn accommodated additional spectators. (Courtesy Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.) |

As the building neared completion, the consistency, size, shape, and pattern of stones in the rock walls continued to be a priority. Longstreth warned the mason to vary the top of the piers with larger, more horizontal stones. In a letter to Smith, he mentioned that larger, darker stones should appear at the bottom and suggested looking for proper stone at the top of the quarry. Superintendent Myers worried about the "dry-wall effect . . . which would cause excessive moisture entering joints." This problem could be avoided by packing the mortar more deeply and inspecting all areas while taking care not to create the "appearance of a tooled joint." [88] The work accomplished through the spring of 1961 was accompanied by an incessant aesthetic critique. In March, stonework was delayed while sub-contractors searched for additional dark-colored stone. The "triangular chinks" in pier T were removed and repaired. And the mason was reminded to "avoid repetitious shapes side by side." When the darker stone arrived at the site, supervisors complained about the thickness of the pieces. The joints were too wide and the stones at the bottom too small. By May 3, the south stone was eighty-five percent complete. In finishing up this important section, the mason was warned against creating a "quoining effect," in other words, suggesting a regular termination of the wall at the corner by using similar square stones. Finally in the fall of 1961, issues involving the stonework no longer related to the actual stones, but to the color of mortar joints and the painted ends of concrete piers. [89]

During the spring of 1961, the architects began preparation for the final stage of the concrete drum—the application of a liquid sealant called Thoroseal. [90] According to Dion Neutra and the product manufacturer, success depended on the effect achieved prior to the application of this final layer. Unfortunately, "the horizontal pour joints read clearly on the ribbed concrete areas between ribs especially on the Cyclorama drum, and rear wall of Auditorium and Mechanical. These must be ground flush afterpatching voids to correct for any possible variation in plane of one pour to the next. While the ribs will tend to overpower slight imperfections, there must be no 'ghost' of the horizontal 'bands' now quite dominant in the picture." Before applying Thoroseal, the firm recommended grinding six inches above and below the visible joints and performing "heavy sandblasting to effectively remove all traces of form oil down to clean concrete." [91] Finally, in May, a product representative of the Thoroseal company applied test samples of the product over certain construction joints to see if it would adequately mask surface deformities. According to Standard Dry Wall Products, the first coating of Thoroseal could be painted on, but a second coat required use of a plastering spray gun that blasted a mixture of Thoroseal and white silica sand. [92] While working with the samples, Gamble discovered "rough bulging patches" that required smoothing out, and recommended bush hammering. The rougher surface would provide a better bond for the Thoroseal. [93] During his next inspection, just a week before Richard Neutra was expected at the site, Longstreth found the surface unacceptable. He predicted that

the expression of the construction joints will telegraph through the final finish particularly because of the irregularities not in the surface between the ribs but of the ribs themselves which cast elongated shadows to accentuate their irregularities. These occur repeatedly at all construction joints and make a staccato shadow pattern at each joint around the drum. Unless the patching of the ribbing is perfect it is felt that this staccato pattern will show through final finish. [94]

Even after a September visit from the EODC to address problems with the application of Thoroseal, Superintendent Myers was still dissatisfied with the exterior finish. Visible shadows and other defects obviously compromised the effort to obtain a smooth concrete surface. Nevertheless, the Superintendent promised that if the contractors could apply another coat and achieve a surface similar to "the northern most of the 12-foot experimental panels," he would accept the job. [95] Project supervisor Smith personally observed the painting foreman, a subcontractor, apply three coatings of Thoroseal just north of the approved northern-most panel. In a follow-up report, Smith described unsightly build up and shadows in the new work. [96]

The Thoroseal problems appear to have been resolved by early December; when Neutra visited the site, he reported the job "favorable and engaging." [97] Most important to Neutra was the opportunity to test lighting conditions, particularly in the exhibit spaces, and color effects, both of which could only be properly evaluated on site. At this point, exhibit frames and dioramas were complete enough for paint analysis. Neutra's letter included a summary of qualities that "obviously put this building outside of the common run of projects," such as the audiovisual system, "the installation of the gigantic painting, the final testing of large dimensioned sliding and swinging doors, the perfection of the finish metal work, intended for long lasting sightliness without running upkeep, of roof viewing decks, etc." [98]

Choosing the "Color

Palette"

Although the structural details of the concrete forms and foundation were of utmost importance throughout construction, the choice of colors ultimately became the most debated aspect of the Gettysburg project. Nearly a year after the color controversy began, Dion Neutra explained to the Park Service that his father "spent years thinking about colors and their effect, and . . . consulted with some of the most advanced thinkers in the field, such as Francis Adler of Johns Hopkins, Baltimore." [99] The architects' original selection of a "palette" of colors for the building, introduced in July 1960, resulted in some significant interior changes. The designers considered the colors of all the interior spaces and facilities, from museum exhibits to restroom toilets. Fearing that the exhibit space would prove too dim, Neutra tried to highlight the displays through a careful selection of colors; in one case, he hoped to substitute the original garnet granite with opalescent ruby-ebony at considerable extra cost. The toilet stalls were to have light gray front doors, pilasters, and screens; the men's toilet would feature maroon cross walls and the women's terra cotta. For the lounge, the architects envisioned a warm char brown carpet, which would complement the rust terrazzo and contrast with lighter plastic covered furniture. The selecting of colors had only just begun.

As Dion Neutra indicated, the color choices involved more than simply tones and patterns that harmonized. Neutra and Alexander thought of color as an architectural element that influenced perception of the entire building mass. They layered closely related shades to create a receding effect in the office wing's west elevation, which also made it seem "to float." The white view deck rail stood out against elements closely related in tone. The hope was always "a subliminal effect," in other words, a sense of the place that visitors would not associate with architectural manipulation. [100]

The color dilemma intensified in November 1960, when John Cabot reported that his office found itself "in almost complete disagreement with the over-all color selections proposed." [101] The Park Service rejected both the brown-multi, a "dark and lifeless color," and the charcoal-multi, except in two sections of the museum where darker accents were useful. Black formica for toilet room shelves, the ticket booth, and the dioramas was impractical due to the propensity for fingerprints on these surfaces. Park designers particularly objected to artificial finishes, such as "the practice of painting wood and steel with aluminum paint, staining ash and fir with a walnut stain, and using wood-grained formica." In response to further selections made by the architects later that month, the Park Service decided to prepare its own color study. [102] Meanwhile, Neutra persuaded the client to accept a revised scheme he called "basically simple: a light warm gray-beige color as the basic element throughout the main level. As contrast in smaller areas, a good dark terrazzo on the stair and upper Lobby as contrast to the light floor on both levels." [103] With the pressure of deadlines mounting, understandable tension developed around the subject of colors. When Dion Neutra requested a site visit in December, John Cabot was quick to deny him the privilege, explaining that his associates were engaged in their own color analysis and would not discuss the subject until after its completion. He then admonished the firm for pressuring the government to make its color decisions and informing the contractor that the client was delaying progress. Cabot considered this both unprofessional and unfair, since the Park Service had waited many months for the architects' previous selections. Over the next few weeks, the architects talked with EODC designer Ann Massey and reached a suitable compromise in terms of "color harmony." [104]

During deliberations over colors for restroom facilities, Neutra and Alexander alluded to the reasoning behind their passionate defense of certain color combinations. Although the architects agreed that the restrooms should be visible from outside, they hoped to resolve the issue "without impairing the dignity and monumental quality of the building." [105] Drawing attention to the restrooms with brightly colored doors or large signs, as the Park Service suggested, would take away from the impression the architects hoped to create. Neutra illustrated this point by comparing the visitor center to "Independence Hall in your city, the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials in Washington, the Taj Mahal, or most any building of prominence," in which "especially accented toilet doors" would be most inappropriate. [106] The architects understood their building to "be in the same class as any of the above albeit of simple materials." Subtle elements set the building apart from utilitarian structures. The substitution of the blue west view deck railing with a more reserved Puritan gray, for example, furthered the visitor center's dignified demeanor. Neutra explained the firm's belief that blue would not only be a dangerous color to juxtapose with the blue sky, but might also impart a "too 'flippant' or 'playful' aspect to what should be a sober building at least in its main exterior effect."

Neutra voiced tentative approval for the color palette from his west coast office, but once on the site, he often changed his mind. [107] After a visit in May 1961, John Cabot reported the architect's "aversion" to the chosen mustard color and agreed to replace it with citron or lemon yellow. [108] By October, Alexander had met with Massey, Longstreth, and Smith to discuss interior finishes and determined that a new plain brown color should replace the chocolate tone. In the meantime, the EODC did not approve the change from white texture coat to beige multi for the curving south wall of the mechanical room and auditorium. Richard Neutra sent a telegram "regarding auditorium beige multi," insisting that, while he agreed with the park "in principle," the "high quality and maintenance freedom of glitter Thoroseal" was superior to an ordinary paint job and worth the extra trouble. He also suggested that the light gray Thoroseal originally contemplated in the specifications might harmonize more effectively with the interior color scheme. The color selection for office partitions also proved more difficult than anticipated. For the partition framework, the architects suggested beige for the metal bases, mustard for door frames, and metallic aluminum gray for end plates, tops, and mullions. The Park Service found this "an extremely busy pattern," and ordered everything in beige to match the rubber cove base. [109]

In a December 1 meeting, the contractor complained about the delays in reaching any color agreements, and by the next week he threatened to stop work if this aspect of the project remained unresolved. Longstreth pointed out that the architects could only recommend colors, not approve them. Although this was true, when it came to artistic issues, the architects operated on a different level from their Park Service collaborators. Seemingly insignificant details, such as "the play of color planes or values in the area of the corridors leading to the museum," took on great architectural importance. The architects' response to a discussion about the color of "Door #13," a minor component of the overall plan, warranted the following explanation:

If you feel that a lighter color for the "frame" (everything on the door but the applied sash which is heavier brown) would not show on the inside anyway, we would appreciate it if we could be allowed to paint this to express the essential quality of this design and meet Mr. Neutra's idea of reduced brightness differential. We propose to treat the "structural" part of the door with Puritan Gray and the "applied sash" in Beaver Brown. [110]

As indicated by their work on the louver window wall, the architects were also concerned with the effect of natural and artificial light on the colors. They asked that contractors delay the final coat of paint until "after simulating the quality of light from the various types of lighting fixtures to be used in windowless areas." [111]

Finally, in early March, Don Benson and Ann Massey took color boards to Gettysburg and presented the completed scheme to Superintendent Myers. [112] As Cabot noted, the Park Service did not include aspects of the exterior—the view deck railing, concrete office wall on the west side, and eastern roof fascia—which still required consideration. Contract and Park Service architects reached agreement on the colors after what Cabot called "some five months of continuous review." [113] Despite this resolution, changes were still proposed as late as August 1961, when Dion Neutra reminded the Superintendent that "this business of getting the best final result does sometimes require a bit of readjusting of ones thinking from time to time. The building will be there a long time and we want to give it everything we've got for the final result." [114]