|

National Park Service

MISSION 66 VISITOR CENTERS The History of a Building Type |

|

CHAPTER 4

Painted Desert Community

Petrified Forest National Park, Apache County,

Arizona

The Mission 66 program brought improvements to national parks throughout the country, most often in the form of "master plans" designed around existing facilities or additions to older buildings. At Petrified Forest National Park in Apache County, Arizona, Mission 66 planners found a clean slate upon which to design a new Park Service headquarters complete with visitor, administrative, maintenance, and residential facilities. When planning began in 1956, the park contained an assortment of buildings—cabins, privately owned concessions, and adobe structures designed by Park Service architects—but these were concentrated along the highway and on mesas overlooking the Painted Desert. The new headquarters would sit alone on a barren site about three-quarters of a mile away. Park Service architects had already drafted plans for a modern administrative complex accompanied by a separate residential development of single-family homes.

Even more exceptional than this opportunity to create a community from scratch was the Park Service's choice of Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander as its designers. The Los Angeles architectural firm had an international reputation for minimalist modern buildings. By hiring Neutra and Alexander to design both the Gettysburg Visitor Center and the Painted Desert Community, Mission 66 planners not only demonstrated faith in modern architecture, but also an unprecedented willingness to experiment with its purest manifestation. The Painted Desert Community Neutra and Alexander envisioned in 1958, with its dense urban center and adjacent "International Style" row housing, was a shocking departure from the standard Mission 66 layout, not to mention the residential neighborhoods envisioned by the client. According to Neutra and Alexander, the flat-roofed, steel and glass buildings addressed the Park Service's tradition of harmonizing with the landscape and regional history through subtle elements, such as low silhouettes, "desert" color, and native plantings. [1] The Park Service would ultimately accept the streamlined visitor center and unfamiliar row housing, but not without questioning aspects of the design and its relationship to park values.

Figure 42. The site of the proposed Painted Desert Community, Painted Desert, Apache County, Arizona, ca. 1958. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

Petrified Forest became a national monument in 1906, a decade before the Park Service was established, but substantial development did not begin until highways were constructed during the 1920s. The completion of Route 66 brought tourists to the north end of the monument, where Highway 180 began its winding path through the Painted Desert and into the Petrified Forest. In anticipation of automobile tourists, entrepreneurs built a trading post for travelers on the rim of the Painted Desert and a store in the Rainbow Forest at the extreme south end of the park. Major Park Service construction first occurred during the 1930s, when the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) began improving park facilities. Led by designer Lyle E. Bennett, the CCC rebuilt the hotel and constructed several ranger residences. The new "pueblo-style" Painted Desert Inn featured carved timbers, tin lighting fixtures, and concrete floors decorated with traditional Native American patterns. Poised on the edge of the canyon rim, the Painted Desert Inn offered visitors spectacular views of the desert, a restaurant, curios, and limited accommodations. [2] This regional example of Park Service Rustic, "inspired by the dwellings of the Pueblo Indians," was mirrored in the employee residences built across the street. These were the types of buildings visitors expected to find in a national park. [3]

The Park Service was still struggling to revive itself after the war during the late 1940s, when designs were submitted for a modern building at Meteor Crater, a privately owned land feature about fifty miles west of Petrified Forest. Prominent architects including Frank Lloyd Wright submitted designs for a museum at the edge of the 570-foot-deep crater. [4] The commission went to Philip Johnson, co-organizer of the 1932 International Style exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and, more recently, architect of the "glass house" (1949) in New Caanan, Connecticut. [5] Johnson's work must have seemed fittingly futuristic to his clients at Meteor Crater. The national interest in space exploration would skyrocket after the success of Sputnik, inspiring many architects to imagine the ramifications of space travel and its impact on design. In his writings of the 1950s, Neutra considered the global effects of "planetary traffic, transport and industrialization," as well as the aesthetic challenge presented by the lunar landscape, a place without cultural history. [6] Mission 66 architecture reflected this contemporary obsession with technological progress.

Although only a short distance from Petrified Forest, Meteor Crater was worlds away in terms of its "park" landscape. The local staff planning for Mission 66 improvement during the mid-fifties had to contend with the monument's former CCC buildings and a motley assortment of souvenir stores and restaurants including Jacob's Trading Post, Olson Curio, and Charles "Indian" Miller's Lion Farm/Painted Desert Park. The Mission 66 plan would not only clear the area of private concessioners, but also create new facilities and improve the road system. The proposal for Petrified Forest included "major development of a Visitor Center, picnic facilities, residential and utility area and location of headquarters in the Painted Desert section near U. S. 66 Highway." [7] By locating the new visitor center and headquarters on the "new Route 66," (now I-40) rather than at the south end, the park defined the modern motorist's experience. Visitors could stop at the center for a rest from the interstate or drive the loop road through the park to Highway 180 and back to I-40. Plans for an interchange into the park from the improved highway became a priority for the new headquarters scheme.

Before the Painted Desert project gained momentum, Park Service planners focused on Mission 66 work in Rainbow Forest at the south end of the park. Improvements would include a museum addition, store, and picnic grounds. Early proposals for enlarging the museum were produced by in-house architects in the summer of 1957. After considering a streamlined, concrete block building with a glass enclosed viewing terrace, the park approved a much simpler scheme by Regional Architect Kenneth Saunders. This 2,400-square-foot "addition to the visitor center" was under construction in October 1958 and completed by January of the next year. [8]

Mission 66 visitor centers were intended to function as "the hub of the park," but at Petrified Forest aspirations for the new headquarters building were even higher. Correspondence from Assistant Director Stratton indicates that in its early planning stages the Painted Desert Community was envisioned as a place where visitors could learn about all the national parks and their shared "National Park concept." [9] According to a fact sheet compiled by the park for newspaper reporters attending the dedication ceremony, the new building would "serve as an Information Center for all of the areas comprising the Park System, the first of its kind designed for this purpose, in the United States." [10] In preparation for this comprehensive new headquarters, the Park Service sent its own designers and planners to Petrified Forest before securing the services of contract architects. In October 1956, Paul Thomas and Glenn Hendrix, landscape architects from the WODC, and Jerome C. Miller, regional landscape architect, met at the park to discuss the part Mission 66 would play in the next master plan. [11] By August 1957, the park had approved an in-house "proposed layout" for the headquarters area. [12] The visitor center and parking for one hundred cars was located off Route 66, with twenty-three units of employee housing grouped around a looping access road some distance from the public facility. The segregation of housing from the visitor center and administrative complex, a primary objective in this scheme, involved building additional roads through the monument. Residences were two- and three-bedroom houses constructed of wood framing and pumice block. In elevation, these are one-story, rectangular buildings with simple, modernist lines—a deliberate departure from traditional Park Service housing. [13]

Over the winter, the Park Service continued to refine its plan for the Painted Desert. Architect Cecil Doty produced sketches for the park's preliminary master plan in February 1958. [14] Doty's sketches show the general layout of the community, with a separate apartment building and dormitory accompanying the visitor center. As in the earlier scheme, the residences are organized in an oval shape around an access road, though in this case much closer to the main complex. Shortly after approval of this plan, the Park Service reconsidered its design of the Painted Desert Community. Dissatisfaction with the proposal may have occurred as a result of a visit from Thomas Vint, chief of design and construction, and Assistant Regional Director Harthon L. Bill. [15] Vint and Bill met with representatives of the Fred Harvey Company on April 6. A few weeks later, the Superintendent and Regional Architect Kenneth M. Saunders traveled to the WODC to discuss the Painted Desert development. At this time, "preliminary talks were held with an Architect-Engineering firm." Shortly after, on April 20, Richard Neutra and Robert Alexander visited the park "to obtain the feel of the area and to discuss proposed work." [16] The next month, the architects discussed their preliminary plans with Conrad Wirth, director of the Park Service. Wirth was not impressed by the residential housing arrangement, which he thought more suited to a crowded urban area than the Painted Desert's endless expanse. According to Vint, Neutra showed little reaction to the criticism and, "although he took notes, he did not explain to us whether they were for the purpose of changing the plans to meet the Director's wishes or for the purpose of developing arguments in support of the plans he has presented." [17] The housing as built suggests the latter.

It appears that Neutra and Alexander began "developing arguments" to support their plans almost immediately. In a brochure entitled "Homes for National Park Service Families on a Wind-Swept Desert," the architects used diagrams, drawings, and text to sell their project, focusing on the special needs of Park Service families and the unique desert site. The community plan included provisions for storage—considered essential for the typical itinerant family—visitors, and social events which usually involved the entire community. The wind-swept aspect of the site was the driving force behind the design. The low profile, compact plan, and private courtyards resulted from wind "known to blast the paint off of exposed automobiles." Since the treeless site lacked visual privacy, the concrete walled patios offered the only opportunity for private green space. Neutra and Alexander addressed Park Service concerns even more explicitly in a discussion of "the dream home in everyone's mind . . . the separate, isolated cottage in the midst of un-touched nature." Although the architects themselves shared this dream of individual homes surrounded by trees, they explained that such an idyllic situation is impossible in most densely populated residential areas. The Painted Desert had the unusual luxury of space, but no foliage to maintain visual privacy. According to the architects, "the vast space around the house would be a menace impossible to maintain, and utility costs would be staggering." Rather than adapting the typical single-family home, Neutra and Alexander favored the Native American method of building a compound of dwellings surrounded by sheltering walls. The Puerco Mesa village became the model for the Painted Desert Community. The architects imagined private homes not only sheltered from the elements, but from the noise and intrusion of neighbors; residents would even enjoy privacy at night without drawing the blinds. The overall plan of the community incorporated larger "oasis" spaces between the rows of houses that served as wind blocks, sound barriers, and sheltered play areas.

Neutra and Alexander also addressed reservations the Park Service entertained regarding the visitor center. The visitor would approach a "cool, shaded, green oasis," where he or she could rest surrounded by services: the concessioner's shop, restaurant, and administration building. Conrad Wirth had advised the separation of Park Service and concessioner facilities, but the architects suggested that the concession and administration buildings share an entrance area "so that one will 'feed' the other." Concession and maintenance walls would be blank in order to focus attention on the lobby entrance, as Wirth desired. In closing, the architects presented the Painted Desert "village" as a microcosm of a city zoned into residential, commercial, recreation, and industrial areas, including apartments, school, civic center, and "parking for visitors from everywhere." [18]

The week before Christmas 1958, WODC Chief Sanford J. Hill and Park Service architect Charles Sigler met at Neutra and Alexander's office to discuss revisions in the plans. After receiving the architects' preliminary designs, the park had developed an alternative layout which relocated major buildings. [19] During this conference, the new plan was reevaluated and in the end, "everyone was pleased to return to the original plan with the Administration-Orientation Building on the right and adjacent to the National Park Service Utility Area while Fred Harvey's store-restaurant was placed to the left and adjacent to their storage building and apartments." [20] Despite this consensus, the Park Service's decision to significantly reduce the square footage of most buildings couldn't have pleased Neutra and Alexander. [21] Although correspondence indicates a good working relationship between client and architects, the firm was obviously inconvenienced by the Park Service's work schedule. According to the regional director, the superintendent and his staff had also "become quite discouraged due to these unavoidable delays." [22] Recent cuts in funding and, finally, the removal of the "package project" from the 1960 fiscal year budget, forced the Park Service to delay construction on all of its contracts—from roads and parking to utilities and buildings. In February 1959, the Director declared that after the architects completed their preliminary drawings, these should be shelved until construction funds were available. [23] Major buildings in "the program of 1958," including the $180,000 administration/orientation facility, were now slated for completion during the 1961 fiscal year. In his report of the meeting to the regional director, Hill revealed that the park had decided not to inform the concessioners of the year delay in construction until after preliminary drawings were approved. The anticipated years of waiting for building to begin "terribly disappointed" both Superintendent Fred Fagergren and the contract architects, who had hoped to start preparation of the working drawings immediately. [24]

Neutra and Alexander had several projects on the drawing boards when they accepted the commission for the Painted Desert Community. The firm was in the midst of designing buildings for St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland; additions to the Museum of Natural History in Dayton, Ohio; the Gettysburg Visitor Center; and plans for the Ferro Chemical Company in Bedford, Ohio; to name a few. Neutra biographer Thomas S. Hines has singled out the St. John's buildings as precedents for the work at Painted Desert. This campus design gathered together several buildings with different functions—classrooms, an auditorium, laboratories, a planetarium—in a compatible arrangement around an open court. The modern brick and flagstone complex stood in close proximity to venerated seventeenth-century buildings. In true modernist fashion, Neutra explained his designs through abstract principles suited to the architectural style; the building attempted "to grasp and express this faith in values that transcend mere historic or modish relativities" through pure form. [25] Like lines in a Shakespearean drama that still ring true today, Neutra hoped to capture a timeless essence. The buildings appear to have been well received by both college officials and the architectural press. According to Hines, poor maintenance subsequently compromised the architects' achievement at St. Johns. A similar fate, exacerbated by faulty construction, would befall the buildings at Painted Desert. [26]

In choosing Neutra and Alexander as architects of the Painted Desert Community and the visitor center at Gettysburg, the Park Service fully accepted modern architecture as appropriate for the Mission 66 program. Other architects hired before and after this firm—Anshen and Allen and Taliesin Associated Architects—worked in the modern style but also designed buildings with "rustic" associations and centered social spaces around domestic features such as fireplaces. For Neutra, architecture could only express the modern age, with its exciting opportunities for efficient contemporary living. Not that Neutra ignored a client's desires; to the contrary, he spent a great deal of time and effort consulting with future residents. But the clients who hired Neutra and Alexander usually preferred the clean lines, bare surfaces, sun-filled rooms, and efficiency of modern design. Although infused with Mission 66 zeal, the National Park Service came equipped with a tradition of environmentally sensitive buildings. It would require all of Neutra's philosophical skill to communicate the appropriateness of the Painted Desert Community.

In the design and construction of the Painted Desert Community, architect and client would deal with the contradictions of decades of modern architecture in microcosm. The Park Service was wary of Neutra's radical row housing. However, when it came to details, Neutra and Alexander pushed the Park Service to consider every aesthetic choice, its associations and the sum of the parts. For example, in response to pictures of sample masonry patterns for the plaza wall submitted by the park, Neutra and Alexander replied that the example was "far too machine-made in appearance to be appropriate." [27] They suggested cutting the stone at the top and bottom, rather than sawing it, to create a less regular pattern. Even more significant, the architects gave an historical precedent for their choice, citing a National Geographic article on the pueblo restoration at Mesa Verde as a good model for laying up the irregular stone veneer. The photographs of cliffs at Wetherill Mesa show intricate pueblo ruins left behind by thirteenth-century American Indians. As he paged through National Geographic, Neutra could hardly have failed to miss an article about the Society's new headquarters in Washington, D.C., the "serene and timeless" structure designed by Edward Durell Stone. According to the architect, the building was "a blend of the National Geographic Society's dignified traditions and the finest modern technological refinements." During the early 1960s, modern architecture was promoted as both respectful of the past and reaching forward to meet the future. [28]

What Will the Neighbors

Think?

In 1949 Neutra appeared on the cover of Time magazine above the caption "What Will the Neighbors Think? [29] Almost ten years later, Neutra and his partner, Robert Alexander, designed the Painted Desert Community in Petrified Forest National Park. As his presence in the popular magazine indicates, Neutra had finally become a mainstream, if eccentric, modern architect. This changing cultural attitude toward modernism was reflected in housing trends over the next decade. Superintendent Fagergren "noted with interest" an article in the September 22, 1958, issue of Life magazine about the conservation benefits of row housing. [30] The article featured Edward D. Stone's design of residential units for eight hundred and sixty-five families and a fifty-acre park, and illustrated how his plan utilized the same area occupied by a conventional housing tract without any green space. The row houses were compact, but light and airy, with elegant concrete grills for privacy, patios and views of a central park. As models for his residential design, Stone looked to ancient Pompeii, French villages, and, closer to home, "the first radical improvement in American community planning," Radburn, New Jersey, designed by Clarence Stein and Henry Wright in 1929. [31] For Neutra, who had grown up among row houses in Vienna, such design was hardly something new. But for Fagergren, who found "the principles stated . . . very similar to the proposed housing for the Painted Desert area," the article provided welcome reassurance. Neutra and Alexander's Painted Desert plan received approval from Park Service officials in early February 1960. [32] The architects were to produce working drawings in preparation for construction beginning that July.

The exceptional nature of the Painted Desert's row housing, at least within Park Service circles, is indicated by a February 17, 1960, memorandum from the Director to the five regions, EODC and WODC. Because recent budget cuts limited park housing expenditures to $20,000 per unit, all future park residences constructed throughout the park system were to be one of five standard plans, including two exclusively for superintendents and one duplex. This direction allowed for no variations except for substantially completed projects under the $20,000 limit. The proposed housing at Painted Desert, which was "to be completed in accordance with the approved Neutra plan," was an exception. The Neutra/Alexander row housing was singled out for special attention because it was "dictated in the interests of economy and good judgment." [33]

The standard plans the Park Service developed for all park employee housing, in place by March 1960, proved to be slightly less restrictive than first announced. Each region was sent the proscribed plans along with a list of "selective components," structural and aesthetic elements, from which it could choose. In addition, allowances could be made for houses on slopes, though it was strongly suggested that architects save money by choosing sites on level ground. The five house plans were all one-story rectangles with horizontal wood paneling covering the exterior and identical windows and doors. The four-bedroom superintendent's house included a two-car garage, and a living room with fireplace and dining area opening onto a terrace in the rear. The other houses had living rooms in the front with dining relegated to an undefined space off the kitchen. The three-bedroom superintendent's residence was identical to the standard three-bedroom except that it included a fireplace and two full baths. In the duplexes, cars were stored in a central carport so that residents could park and enter the house from the kitchen. Although the Park Service invested considerable effort in the development of easily built, low-cost housing, it did so at the expense of individual creativity, the architect's prerogative. [34]

In March, the park received a memorandum from Sanford Hill enumerating the extra costs required by the Neutra-Alexander housing designs. Fagergren feared that funding might be withdrawn if the park exceeded the budget, and explained that local contractors estimated higher costs for Park Service projects because they demanded better materials and included an extra charge for "government red tape." He suggested that the "justification data" for the Neutra-Alexander residences emphasize additional expenses—such as the region's higher union wage, expenses for travel to and from the site, and the high cost of skilled laborers in Arizona since the strike of 1959. [35]

Superintendent Fagergren was responsible, in large part, for promoting the Neutra and Alexander plans within the Park Service. In April 1960, he wrote to the Regional Director in defense of the concrete walls enclosing the Painted Desert Community.

The Neutra-Alexander hous [sic] plans, particularly their proposal for a high wall enclosed yard or patio, have provoked considerable discussion. Hence I was and thought you might be interested in a comment made by Superintendent and Mrs. Jim Eden while I was visiting them at Page last week. They are building a solid wood fence about 7' high and said, "Everyone in Page, who can, is building a fence to protect themselves from the wind." Wind conditions at Page and Petrified Forest I would judge to be comparable. [36]

The Chief of Operations, Jerome C. Miller, responded to Fagergren's letter with his own thoughts on wind resistance, noting that Page had to deal with sand as well as dust. Finally, after discussing the matter with a colleague, he was convinced "to some extent." [37] Although Miller was most concerned with the effectiveness of the wind block, Fagergren's remarks suggest that criticism of the walls was as much aesthetic as functional.

The row housing remained the most controversial aspect of the plan, and in February the Park Service suggested a new arrangement for the residential units, as illustrated in a representative sketch. [38] Neutra and Alexander's original plan included three different housing unit types—"A" at 1280 square feet and three bedrooms, "B" at 1032 square feet and two bedrooms, and "C" at 1346 square feet and three bedrooms. [39]WODC Chief Sanford Hill sent Neutra and Alexander floor and plot plan revisions and requested their assistance in producing new working drawings and specifications. Rather than using three "A" and three "C" units in each six-unit grouping, WODC preferred flipping the C's and using them for all units. [40] This arrangement had the advantage of providing "access to each patio without having to go through each respective house." The new plan would allow the park to build additional housing adjacent the "A" units, which had been considered in the January 1958 drawings. After approving the architects' revision of these corrections, Superintendent Fagergren suggested some further alterations, including a window in the kitchen for the housewife to observe her child in the courtyard and a "dinette" in place of the "pass through" in the kitchen area. [41] By this time, the Park Service appears to have been resigned to the aesthetics of row housing and concerned only with functional issues.

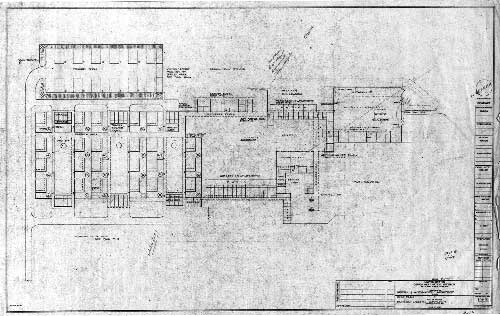

Figure 43. Preliminary site plan, Painted Desert Community, January 1959. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) (click on image for larger size) |

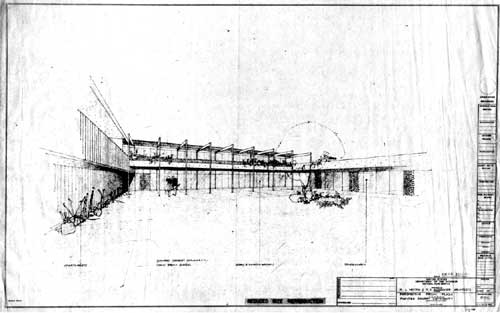

Figure 44. "Perspective from Plaza," Painted Desert Community, January 1959. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) (click on image for larger size) |

The designs Neutra and Alexander finished in January 1959 contained all of the elements laid out by Park Service planners, but the arrangement was very different. In-house designers were equally modern in their depiction of streamlined, concrete housing, concrete walls, and simple, rectangular buildings. All these choices depended on adherence to a modernist aesthetic. But the modern aspect of Neutra and Alexander's plan lay in the organization of spaces and the separation of public areas from administrative and residential zones. The parking lot provided easy access to the two places most important to visitors—the visitor center and the concessioner's building. Park offices were located above the public spaces and maintenance in the rear. The public buildings formed two sides of a courtyard, and although apartments for employees formed a third side, these were hidden by a concrete wall. The fourth side of the courtyard opened up to park apartments carefully hidden by planters and a landscaped area. Most unique for a plan of this type, housing was organized into four rows of one-story units just a short walk from the rest of the complex. In principle, the design achieved the Mission 66 goal of concentrating development in a limited space and therefore conserving natural resources. [42] The Painted Desert Community received a residential award citation from Progressive Architecture in January 1959, when the complex was still only a set of drawings. The magazine praised the most extraordinary aspect of the Community, its "compoundlike grouping of L-shaped houses with wind-shielding walls to the south and west and small high-walled patios where devoted care can produce oases of natural growth." [43]

Building the Painted Desert

Community

In April 1961, Petrified Forest National Monument prepared promotional material for "special visitors en route" to the Mission 66 Frontier Conference at Grand Canyon. The information included an update on Mission 66 development at Petrified Forest, a copy of the local magazine Agatized Rainbows, and a piece of polished petrified wood, courtesy of the Rainbow Forest Lodge. These honored guests may have also witnessed tangible evidence of Mission 66 progress—the laying of foundations at Painted Desert. [44] The construction of the Community had begun in January under four separate contracts. After the standard bidding process, the contract for utility systems was awarded to the McCormick Construction Company of El Paso. [45] The Kealy Construction Company, building engineers and contractors from Farmington, New Mexico, began work on their contract for the administration building and apartments in April. The residential job went to Rasmussen Construction Company of Orem, Utah. A few months later, the Rasmussen Company also won the contract for the community building, the maintenance yard behind the administration building, and a trailer park adjacent to the residential area. The contractor for the Fred Harvey Company's private concession, the "Painted Desert Oasis," would be determined as construction progressed.

The Administration Building, Apartment House and Gatehouse: Kealy Construction Company

When the Park Service's project supervisor, Eugene T. Mott, arrived at the building site on March 27, 1961, McCormick Construction Company was installing water, sewer, and electrical systems. The Kealy Company began masonry work on the administration and apartment buildings in early April, but progress was slowed almost immediately. Although the steel and concrete frame buildings appeared simple, Neutra and Alexander specified materials and techniques to achieve subtle aesthetic affects. Cement blocks were special ordered, with each lot dyed and the color chosen based on "the assumption that the interior and aggregate of these blocks will be exposed by sandblasting after erection, and immediately prior to waterproofing . . ." [46] Neutra and Alexander even requested a sample of the contractor's sandblasting ability, as displayed on a typical block. The special order of concrete and the drying and blasting process resulted in expensive construction delays during the first months of Kealy's contract. [47]

Figure 45. The visitor center and apartments under construction, ca. 1961, before work began on the Fred Harvey concession building. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

As they waited for the blocks to arrive, contractors began to assemble the steel frame in concrete bases, which were later removed and reset "exactly as shown in the drawings." In early July, interior columns were set in their new bases and concrete slabs poured according to detailed specifications. Once the mortar color was approved, the final pour was made on the patio foundation walls. By the end of the next month, the second floor steel decking was under construction and wood framing of partitions and floor joists had begun in the apartment building. On October 1, 1961, the building was half finished and "very good progress was being made." Excavation of the site for the new gatehouse began in early November. Despite bad weather, the contractors completed all the aluminum framing around the gatehouse and administration building and started setting the glass in the visitor center.

Figure 46. The original entrance to the visitor center during construction, ca. 1961. Until the 1970s, the entrance was recessed and faced the corner of the parking lot. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The Kealy Company continued to work sporadically over the winter, and by March 1962, it was concentrating on the planters, terrace and balcony as well as the louver enclosure on the apartment house roof. At this point, with the administration building about eighty percent complete, Kealy's vice-president Harry J. Mills expressed extreme frustration with Neutra and Alexander, citing the lack of a "room finish schedule" as a major reason for subsequent construction problems. Mills wrote that in "twenty-four years in the construction industry, we have never before encountered a job approaching this size without a room finish schedule as a part of the contract documents." He went on to describe the lacking schedule by its dictionary definition—a list of details—and explained the confusion arising from its non-existence. Evidently, the architects were exacting in their requests and attention to details, but baffled the contractors with "the obscurity" of their plans. After absolving the Park Service of any blame in the situation, Mills mentioned that Kealy's job superintendent had been granted a leave of absence "due to the nervous strain and feeling of failure, brought on by the many worries and problems of this project." This was the superintendent's first failure to complete a project. [48]

A letter from Neutra and Alexander dated December 1, 1961, indicates that conflict had been brewing over several months. Dion Neutra, representing his father's firm, refuted the contractor's claims and blamed Kealy for "incomplete study of the drawings." On their part, the architects, who were "running way into the red on each project," protested the inordinate amount of time spent reviewing shop drawings, inadequate funds, and the failure to determine manufactures and products during the early stages of construction. As these comments suggest, poor communication was one factor contributing to the slow and costly construction of the Painted Desert Community. The contractors may have needed especially clear instructions to complete the building, which was not only an extensive project, but probably very different from any other job they had encountered. Matters were complicated by the fact that, in many instances, the architectural firm, Park Service architects, and superintendent all attempted to advise the contractors, an arrangement guaranteeing delays and misunderstandings. Information was frequently relayed to the contractor through the superintendent, who usually paraphrased the architects' requirements. Since the client was also its own architectural firm, each stage of the progress was further supervised by many experts and their supervisors. In addition, funding was a continual problem throughout the project; certainly delays wouldn't have been as infuriating if the budget allowed for compensation. Most frustrating for the architects must have been the continual insistence on cutting costs, reductions that ultimately infringed on the integrity of their design. [49]

Although considered ninety-eight percent finished by May 31, 1962, completion of the administration and apartment buildings awaited the arrival of customized ceramic tile. The special tile not only delayed construction but also angered contractors and subcontractors, who could not obtain the requested floor covering. According to Neutra and Alexander, the desired glazed granite tile was merely ordinary unglazed tile covered with a clear glaze and fired—a process easily performed by any tile manufacturer. The architects appreciated this type of glazed surface both for its appearance and durability. Most of the rooms in the administration building were to have white granite tile covering the floors and snow granite on the walls. To the contractors, such devotion to a difference of texture or sheen appeared foolish when valuable time was at stake. The Kealy Company was appeased after the park granted its request for an extension of construction time due to the tile delays. [50]

As Kealy Company officials ironed out their administrative problems, concrete was poured for the north sidewalk and reflective pool, the final pour of the contract. In early April, the metal kitchens were installed and interior millwork begun, including hanging the wood doors. A layer of silicone water repellent was applied to the exterior concrete blocks. Final work on the interior continued through early May, with the installation of "mill-work, hardwood veneered panels in the lobby, hardware on the closet doors and a good amount of painting." As the Kealy Company awaited arrival of the ceramic tile, preparations were made for an anticipated visit from project architect John Rollow of Neutra and Alexander and Boris M. Lemos, the firm's consulting mechanical engineer. Inspector Mott estimated a completion date of June 28, 1962, but poor installation of the ceramic tile resulted in further delays. Finally on July 7, the buildings were considered complete and the government expected to "begin moving into the buildings right away."

Superintendent Fagergren officially announced the movement of park headquarters from the Rainbow Forest to the Painted Desert on July 18, 1962. [51] After the exhibit installation, anticipated to occur the next week, the building would be open for visitors. On August 4, 1962, employees of the Petrified Forest were invited to a pot-luck dinner and tour of the new visitor center. The public received its first glimpse inside the building August 12 and was welcomed to a special open house during a celebration of Founders Day on the 26. Visitors toured the "enlarged and new exhibit room, and the new building that serves not only as a visitor center, but houses administrative offices," as well as "other recently completed facilities in the 'Mission 66.'" [52] Exhibits in the visitor center lobby consisted of a 4- by 6-foot vertical wall panel describing the park and a similar horizontal panel about southwestern parks and monuments mounted adjacent the information desk. [53] The room was also decorated with photo murals and specimens of petrified wood. Dedication of the facility would occur after completion of the Fred Harvey building, and, the Superintendent hoped, once the monument received its long awaited national park designation. When Petrified Forest became the 31st national park on December 9, 1962, the administration awaited only the completion of construction to acknowledge its Mission 66 improvements. [54]

Figure 47. Visitor Center lobby, Painted Desert Community, ca. 1963. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

Shortly after the visitor center's public opening, Assistant Director Stratton wrote to the Superintendent to commend the Painted Desert Community and his patience throughout its lengthy construction. The letter was inspired by comments from Dr. Edward B. Danson, of the Park Service's National Advisory Board, who was very impressed by the building. Stratton explained the Park Service's previous prejudice against the Community as a general fear of change.

Whenever a new architectural thought is broached, even though the philosophic base may be age old, there is a National Park Service instinct, bred by conservatism, to feel the result may lead to contentious criticism. However some of our very best buildings of recent years that may cause immediate critical response, are, in fact, those that within a very short period of time turn out to be our best;—those on which we received the most favorable comments. [55]

The Painted Desert Community had certainly pushed the Park Service beyond any standard model of modern architecture. If Stratton's comments proved true, the complex would be hailed as a great success for Mission 66.

Building the Painted Desert

Community (continued)

The Residential Colony and the Maintenance Building, Community Building, Trailer Park Building, and Vehicular Storage Shed: Rasmussen Construction Company

Weekly construction reports kept by the Park Service's project supervisor, Eugene Mott, indicate serious problems with Rasumussen Construction Company from the beginning of the initial contract in July 1961. During their first week of work, Mott noticed that the contractors did not "take into consideration the amount of fill work to be done and the height of the building foundations required." He suspected that these miscalculations had resulted in the company's low bid on the project. Mott soon learned that Rasmussen did not belong to a union and that he had recently failed to complete work at the Grand Canyon. Despite these early warning signals, the park awarded the Rasmussen Company the contract for the maintenance, community, and trailer park buildings. Work on this second project began in early March 1962, when the Company's residences were almost half complete.

The Rasmussen Construction Company had begun building the eighteen Painted Desert Community residences in July 1962. The concrete and steel frame houses were to be of concrete block matching the other buildings, with interior walls finished exactly like the exteriors "to maintain a continuity of appearance and provide a linear characteristic to the wall pattern." [56] Windows and doors were aluminum framed. Except for the interior concrete walls, surfaces were finished with plaster and gypsum board. Once construction advanced, Neutra and Alexander reported a "variation" in their specifications for concrete-block construction. The contractors had used closed-end blocks in areas with vertical reinforcing steel that needed open end blocks to accurately place the steel. The architects explained how to correct the problem through the use of a "centering device." Similar open blocks were especially important in the community building, which required "most careful workmanship on masonry work." [57] By May 1962, cracks had developed in the concrete walls of the apartments and administration buildings, and in preparation for the community building, the architects suggested placing control joints in the walls. In addition, they advised testing the concrete block for deficiencies in absorption, shrinkage, and expansion capability. [58]

During this repair progress, Superintendent Fagergren revealed the first hint of serious problems with the Rasmussen Company. Not only was work proceeding slowly on the residences, but it was not "conducted in a business like manner." He suspected that the cost of "inspection and supervision has been excessive in order to gain compliance with specifications." [59] At this early date, with the projects in full swing, the superintendent could not know how serious the situation would become. By mid-March 1962, Mott reported that Rasmussen had been given thirty days to redeem himself and the contract. In April he still required "constant vigilance." As work slowly continued, the Rasmussen Company fell further and further behind in the construction schedule, not to mention in paying its debts. Over the winter of 1961-1962, park officials reviewed the previous work and discovered multiple instances of failure to comply with specifications. Problems ranged from insufficient bolts to poorly fitting beams. The Park Service withheld payment until submittal of payrolls. The Company was warned that a visiting inspector, Red Newcomb, would enforce "strict compliance with the plans and specifications." [60] Finally, in October 1962, the residences were inspected and approved on the condition that Rasmussen address several issues: the saturation of walls during the rainy season, a fuel leak that damaged the roof of one unit, and waterproofing of the carports. [61]

Throughout construction, the Park Service consulted Neutra and Alexander on every aspect of interiors and then forwarded this information to the contractors and subcontractors. The architects designed a cabinet arrangement and based their approval of Youngstown kitchens on the provision that the bottom cabinet contain "two large drawers." They also selected materials and colors for cabinet tops and splashes. Superintendent Fagergren sent the architects bundles of brochures, including information on Norse refrigerators and grills from the R. E. Naylor Company. The architects were to examine a sample of Hermosa tile and choose the appropriate color. All of the mechanical systems and light fixtures were also architect approved.

Inspector Mott reluctantly accepted the residences as complete on August 24, 1962. According to Mott, Rasmussen had "in his own disorganized way, done the best that he is capable of doing." At that point, $3,800 had accumulated in liquidated damages. While the Park Service attempted to recoup its losses, park families began moving into the new row housing. The eighteen units were organized into four rows, the two central consisting of blocks of six units each. Covered walkways supported by smooth metal poles led to the fronts of the rows. The floor plans were flipped, so that the bedroom and living wings alternated. Single rows of units facing northwest had a front door and clerestory windows with entry to the patio from the rear. In the first row of units in each of the double rows, access to both living area and patio was from the front because the patio areas were enclosed by the rear walls of adjacent apartments. All of the houses were oriented toward the patio spaces, which were "outdoor rooms" intended to block any external views. The wall of the living room facing the patio was all windows. Each bedroom featured a strip window facing the patio space and one wall of bare concrete block. Veneered golden-colored woodwork contrasted with the aluminum-framed louver windows and exposed concrete surfaces.

The character of the row housing was strongly influenced by the color scheme—bright white, metallic gray, and bright blues and golds. Inside, the houses were painted white, tiled in "salt n-pepper," "dawn blue" or "inca gold," and equipped with "frost white," "primrose" or "aqua" kitchen counters. The interior colors were coordinated with the exterior in five schemes, "A" through "E," which were sprinkled throughout the four rows of units. For example, unit "A" had light yellow and gold accents, primrose counters, gold ceramic tiles, and a gold exterior. Unit "C" was painted with light and dark blue interior accents and featured white counters, beige cabinets, and white tile. Exterior plaster surfaces were white, but doors were color-coordinated, along with the carports on either end of each row, in four groups: gold on the east; rust for the front of the next row, but dark yellow for the back; light yellow for the front of the third row, but blue for the back; light blue for the west. The carports were painted to match the front doors, from east to west—gold, dark yellow, and blue. [62]

Once residents had moved into the housing, Neutra composed suggestions for furnishing the units. Despite the reduced room sizes, the result of congressional budget cuts, Neutra believed that a feeling of spaciousness could be obtained by hanging pictures to be viewed from a seated position. Drapes should be light colored so that they might open up the view to the patio, which was intended as an outdoor living area. Neutra's obsession with light and sun is perhaps best conveyed by his ideas for the individual patios and their relationship to the house. "There against the gray block walls light blooming plants and shrubs, preferably flowering white, cream, lemon, yellow or orange, will give the best effect and convey the feeling of sun penetrating, without any glare, into the living areas of the occupant family." [63] The architect also suggested light-colored carpets and offered to provide additional advice on the selection of appropriate furniture, if necessary.

As park employees adjusted to their new homes, Rasmussen continued work on the community and maintenance buildings, scheduled for completion November 2, 1962. Evidently, pressure from the Company's financial backer, Dr. F. B. Wheelwright (Rasmussen's father-in-law), led to greater effort on this contract. By September 15, the roof framing for the community building was in place. A few months later a crack had developed in the parapet wall on the northwest corner of the building.

The contractors rebuilt the wall with 8-inch-thick blocks instead of the required 12-inch blocks, thereby causing further delay and accruing additional expenses while the error was corrected. Although interior partitions and furred ceilings had been completed in the maintenance and community buildings by the end of October, the Park Service was considering ending the contract. This threat seems to have motivated the contractor to speed up work. On November 11, the day before the buildings were scheduled for completion, the Ferguson canopy doors were installed on the maintenance shop and the curtain tracks in the community building. Work dragged on as the contractors waited for a delivery of roof gravel from Barstow, California. Mott predicted that Rasmussen would use the architect's failure to send the color schedule on time as an excuse for delays; in fact, he was already waiting for "the roll-up door, sliding door, aluminum door, louver windows" and other items. The Christmas holidays passed with the building looming at the ninety-nine percent complete mark.

Although the maintenance, community, and utility buildings were accepted as substantially complete by late March 1963, the construction ordeal was only just beginning. In February, the Rasmussen Company had filed an appeal to its contract with the government for the eighteen residences. Over the next few years, contractor and client would argue over the liquidated damages assessed as the result of extensive delays. In the meantime, Packer Construction Company, which had recently constructed the Fred Harvey concession building, completed the final work on Rasmussen's maintenance contract in September 1963. The modest maintenance and utility buildings showed no sign of the effort that went into their construction. These functional structures consisted of two rectangular wings behind the visitor center; high concrete walls blocked any view from the parking lot. Park Service employees entered the parking and service compound from the rear. Maintenance offices could also be reached through the visitor center lobby. The community building stood between the Park Service apartments and the housing units. An aluminum roll-up door formed almost the entire front of the building, and opened to reveal a large rectangular meeting space with a movie screen at the far end. The high ceiling and clerestory windows contributed to its theatrical effect. Floors were rubber tile and walls plastered. This "multi-purpose room" included a kitchen and storage space. The trailer park building, located at the far corner of the complex, provided temporary employees with bathrooms, storage, and laundry facilities. Twelve trailer spaces were graded and planted.

Building the Painted Desert

Community (continued)

The Fred Harvey Building: Packer Construction Company

Concrete was poured for the foundation of the Fred Harvey building in early September 1962. Inspector Mott was encouraged by the engineer's initial efforts, but his enthusiasm waned after delivery delays and poor weather slowed progress. The metal roof decking and structural steel framing was not in place until mid-November, and even this work was slowed by "a jurisdictional dispute between the steel workers and the sheet metal workers." The building was about half complete on December 16, 1962, and the "aluminum window walls" were added the next week. Construction was considered on schedule January 5, the last day Inspector Mott reported on the project. The glass and aluminum wall was in place and work had begun on interior plastering.

Figure 48. The Fred Harvey Building and courtyard. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

During the building's design stage, Neutra had urged the Fred Harvey Company to allow a solid concrete front facade, rather than standard shop windows that would make the entire complex "appear like a shopping center, adjacent to a shoppers parking place." [64]Although not overjoyed with the conspicuous location of the gas station, Neutra thought the bare wall, "without any displays or advertisings," a proper approach to the park plaza. This entrance was carefully calculated to give a tantalizing view of the landscaping and reflecting pool, before revealing the services of the Fred Harvey Trading Center, Restaurant, and Lunch Room through a steel and glass wall. From the parking lot, the only decoration on the facade of the concessioner's building was the curving script of "Fred Harvey" above steel letters announcing "Painted Desert Oasis." To enter the building, visitors first walked into the open plaza and then turned left to face the wall of shop windows and the glass double-door entrance. The shop was connected to a lunchroom with counter, which could also be entered from the other end of the plaza. A series of evenly spaced tile-covered columns ran the length of the window wall. The small yellow and white tiles resembled those used on the Gettysburg Cyclorama ramp in size and texture.

The School and Teacherage

Although an integral part of the plan, the school was not constructed along with the rest of the complex and remained incomplete at the dedication ceremony. An "elementary school site plan" and technical description of the 1.14-acre area had been drawn in April 1961, and the park superintendent met with the superintendent of schools to discuss the facility that September. According to annual reports, the park expected the school building and "teacherage" to be complete by June 1962. [65] The St. Johns School Board was to receive funds from the Office of Education (Housing and Home Finance Agency) to complete the project. Perhaps because of this combination of federal and local funding, the contract for the school was postponed. Neutra was still meeting with the superintendent to discuss plans for the school in January 1963. In a letter to Clark Stratton, head of Park Service Design and Construction, he expressed hope that work could begin on "the rural school building with which we had been concerned also since the beginning of our design studies." However, final working drawings dated March 11, 1963, were produced not by Neutra and Alexander, but by Robert E. Alexander, F.A.I.A. & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants. [66] The school was under construction by Arimexal, Inc., in early March 1964, but then quickly stopped due "to non-payment of claims." The park anticipated that the bonding company would have to take over the contract.

The rectangular school building was located between the community building and the residential units, but oriented not towards the neighborhood, but the southern desert expanse as if to protect students from distractions. Other than a strip of windows, "Painted Desert School" in metal letters provided the only ornament on the concrete block of the south facade. The plan consisted of two open classrooms separated by an optional partition. Movable partitions further divided one side of the first classroom. Below the windows, built-in cabinets extended the length of the rooms. A corridor led from the central classroom to a storage area for students, a supply closet, and an office. Bathrooms were also located in this area.

Figure 49. Painted Desert School, July 1969. (Photo by Huntsman. Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The teachers' residences, called the teacherage in park reports, were near the corner of the school, the first in the second row of residential units. The only duplex, the teacherage consisted of two one-bedroom apartments sharing a central wall that extended into the patio area. Each unit was equipped with a small kitchen and dining area in one corner of the living room. A utility room and bathroom were located off the bedroom. As in the row houses, selected walls were exposed concrete. When the school was closed in the early 1980s, the teacherage became regular employee housing.

Final work on the Painted Desert Community's physical plant and the visitor center's interpretive exhibits continued into the spring of 1964. A contract for "covered walks and related work," including fences, was awarded to Glen D. Plumb of St. Johns, Arizona, in May, as the Packer Company finished up the "grounds improvement, headquarters area." Plans had been received for the wayside exhibits and bids were about to be advertised. Over the summer, parts of the exhibits were prepared at Grand Canyon and a contract artist completed work on some of the panels.

The Painted Desert

Community

The Painted Desert Community, estimated to have been completed by July 17, 1962, was finally finished in the last week of April 1963. During the course of construction, Inspector Mott noticed a change in attitude toward the building as people became more accustomed to the style and began to appreciate some of the design decisions. [67] He concluded his final report with the following statement: "When this housing project was first begun and up until the residences were occupied, I heard many critical comments concerning their design. Now I hear more favorable comments. After nearly two years in the area I'm satisfied that the walls are definitely required to combat the high winds and dust. Others are finding this to be true also." The completion of the new $1,460,000 facility was celebrated at a dedication ceremony on October 27, 1963. The event, co-sponsored by the Holbrook-Petrified Forest Chamber of Commerce, began at 1:30 p.m. with a musical prelude and national anthem performed by the 541st Air Force Band. A speaker's stand was erected on the plaza facing the visitor center, and guests sat in the space surrounding the planters. After a general welcome by Superintendent Humberger, Director Wirth and Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior Orren Beaty, Jr., said a few words. The dedication address was delivered by Dr. Edward B. Danson, Jr., secretary of the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments. Superintendent Humberger then invited guests to tour the facilities and witness the ribbon cutting ceremony at the visitor center. Richard Neutra posed with park officials in front of the un-cut ribbon. [68]

Figure 50. Visitors entered the Painted Desert Visitor Center from the parking lot and the Fred Harvey Building from the courtyard. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The new visitor center was the highlight of the celebration. In the drab desert environment, its bright white concrete and aluminum buildings sparkled. No one had ever seen anything quite like it. Upon pulling into the visitor center parking lot, visitors immediately read the sign, "Painted Desert Visitor Center" and recognized the Park Service's arrowhead logo. Restrooms were prominently located to the right; although actually within the visitor center building, they were entered from outside. The high walls screening the maintenance area from the parking lot, the Fred Harvey building, and this section of the administration building were "desert-colored" concrete block. In contrast, the entrance to the visitor center was indicated by a smooth white exterior and floor-to-ceiling windows, which provided a glimpse of the spacious lobby. Visitors entered double glass doors and were naturally drawn towards the information desk near the center of the room. On the wall above the desk, metal capital letters attached directly to the wall announced that "Petrified Forest National Park is one of many areas administered by the National Park Service within the United States to serve the inspirational and recreational needs of this and future generations and to insure perpetual preservation of a heritage rich in superlative scenery and significant historical and cultural landmarks." On either side of the desk, exhibit panels, which Neutra called "translucency illuminating boxes," were arranged at eye-level and a map and "slide illuminating case" mounted directly on the exposed concrete block walls. The floor was shimmering blue tile. A wall of floor-to-ceiling windows and steel columns faced the courtyard. It was an open, elegant, functional space.

Figure 51. The second floor apartments viewed from the courtyard outside the Visitor Center. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

Figure 52. Richard Neutra chats with a resident of the Painted Desert Community in her apartment. (Photo by Beinlich Photography. Courtesy Petrified Forest National Park archives.) |

As they strolled around the plaza, visitors must have wondered about the cantilevered steel balcony above the visitor center. A stairway at the far end of the lobby led up to the second-floor administrative offices. The rooms on the courtyard side opened out onto the terrace, which also connected to the corridor running parallel to the upper level of Park Service apartments. From the plaza, visitors saw this corridor as a horizontal strip window above a masonry wall—a facade without any hint of domesticity. Although the Park Service employees' private and public spaces were located in close proximity to the visitor center, park visitors were unaware of this secret world.

In their wanderings outside the visitor center, visitors were also expected to examine the reflecting pool in the far corner of the plaza, an exotic spot in this desert environment. The architectural firm and the Park Service collaborated in the design of the plaza, and in February 1962, Neutra and naturalist Philip F. Van Cleave exchanged ideas about its landscaping. Initially, Neutra overwhelmed Park Service personnel with plans for a lush "Triassic" garden, but in subsequent correspondence, the architect explained that he merely hoped to demonstrate the "degeneration" of the giant prehistoric species into petrified specimens and the "tiny relatives" of the present day. Superintendent Fagergren agreed that the planters and pool might be devoted to such an exhibit. In describing his ideas for the central space, Neutra explained that the entire scheme was based on the mesa shelters of the Puerco Indians. Through careful planning and landscaping, the buildings would harmonize with the landscape and relate to the region's history.

The desert planting for example, around the project at the entrance of Petrified Forest National Park was to be brought right to the wide enclosure walls in more or less desert colored brick. Most window openings would turn to interior patios or circumwalled garden courts protected against the desiccating and evaporating desert winds. The center plaza was to become a demonstration of such wind protected planting area, as it is also exemplified by the Puerco Indian village which in archeological finds and ruins is being inspected by the visitor. [69]

These ancient residents crowded together in underground dwellings that provided both "wind-stillness" and shade. The park still contained remnants of prehistoric settlements sprinkled among the petrified trees, and colorful pieces of rock recalling the area's Triassic past, when the deserts were verdant with growth and wildlife. In the plaza space, Neutra hoped to introduce visitors to this ancient park history with a glimpse of the region's incredible transformation from lush forest to arid desert. Relatives of prehistoric trees, such as the ginkgo biloba and araucaria were arranged alone and in pairs, along with the "resurrection plant," horsetails or equisetum and other appropriate native species. [70]Neutra hoped that the plaza landscape would include a "living lungfish, so that one could show it off to the visitors and give them a chance to grasp what this region had been like so long ago." [71] This "prehistoric" landscape was intended to re-establish a lost connection with the past.

The preliminary study for the plaza produced by the Park Service landscape architecture office in March implemented many of these planting ideas. A low planter ran parallel to the front facade of the visitor center; unidentified trees in tubs lined the glass wall of the Fred Harvey building. There was a rectangular planting bed in front of this row of trees and a bench-high planter featuring a specimen sycamore. Across the courtyard, two ginkos sheltered the apartments. The corner nearest the visitor center featured a petrified tree exhibit. To the north, the reflecting pool was supplemented by a Triassic swamp exhibit, a more naturalistic body of water with representative flora. Neutra consulted professors of botany and paleontology at the University of Southern California, the University of California at Los Angeles, and San Jose State College, both to determine his selection of plants and their suitability to the patio environment. After his research, he felt confident that the garden would not require special maintenance. By January 1963, Neutra had discussed the landscaping plans with Volney J. Westley and forwarded recommendations to the regional director, Thomas Allen. Screen planting was an important part of the overall scheme. Plantings south of the entrance road were necessary to block the view of visitor carports; chamisia would be useful in achieving this purpose. From February to April, the Park Service produced additional planting plans, including landscaping of the open area between the residences and the courtyard. Drawings for "the plaza and related areas" included specifications for benches—both wood and stone slab—waste paper baskets, drinking fountains, and planters. Special attention was paid to the texture of surfaces, the pebble-finish concrete of the plaza, and the combed concrete of the raised planters, also used as a transition between the plaza and the community area. Selected riverbed stones filled the flush planters. [72] If used according to plan, the plaza would become an extension of the park's interpretive program, as rangers describing the evolution of the landscape could point to miniature examples growing in the planters outside.

Figure 53. Painted Desert Community, exterior view of Visitor Center and plaza. The pool in the foreground was intended to house the "living lungfish." (Photo by Huntsman, July 1969. Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The Painted Desert Community of 1999 bears little resemblance to the pristine white complex completed in 1963. The early years of the Community are fondly remembered by the park's chief of maintenance, Charlene Yazzie, who grew up in unit #213. When the family moved into the new row housing in 1964, Yazzie's father had just begun his thirty-one year career in the park maintenance department. The family enjoyed the benefits of a close-knit neighborhood, with public services such as a post office and public branch library located within the Community. Yazzie and her three brothers and sisters attended elementary school in the same classroom each year, moving up a row of chairs as they advanced through each grade. The children played tennis and basketball in courts behind the school, but also explored the Painted Desert canyons, yards, and community spaces. An unspoken agreement kept them from the visitor and administration areas, except to visit the Fred Harvey popcorn machine. On Friday nights, residents gathered at the community building for movies. Barbecues and other social events were commonplace, and sometimes students performed plays on a stage erected in front of the movie screen. During these early years, every apartment was full, with at least three children to each household. But, beginning in the early 1970s, the families stopped coming and things began to change. There were no longer enough children to require a school. Occupants of the row housing were increasingly transient, usually temporary researchers and seasonal employees. Today, Yazzie works in the offices once occupied by her father. Although many aspects of her job are similar, the emphasis is no longer on maintaining the existing facilities, but on preserving them. [73]

A Case of "Gross Negligence":

Structural Problems at the Painted Desert

One rainy September Sunday in 1962, Inspector Mott noticed some cracks in concrete that had been poured on undisturbed grade. It was a damp day, and since he had "observed a similar condition at Dinosaur Visitor Center," Mott concluded that the earth below the foundation was unstable, perhaps even the bentonite that had so damaged Dinosaur. By January 1963, the park assembled its own specialists, Richard Neutra, and Dean Rasmussen for a final inspection of the Community, Trailer Park, and Maintenance Building. The group discovered enough deficiences in construction to consider a lawsuit. With what must have seemed like astonishing audacity to the Park Service, the Rasmussen Company appealed its contract for the residences, thereby forcing the park to seek damages. On July 8, 1963, Department Counsel Murray Crosse represented the government in a hearing of the "contract appeal case of Rasmussen Construction Company." During this process, Chief Architect Jerry Riddell and Robert Alexander conducted an inspection, only to find that "all the buildings of the Painted Desert Community have been affected by varying degrees of soil movement," clear evidence of "gross negligence." [74] The problems ranged from blatant failure to follow specifications for reinforcing steel to poor masonry and shoddy workmanship attributed to the many change orders that had resulted from budget cutbacks. In a follow-up report, Alexander advised condemning the buildings because, in the event of an earthquake, "many lives would be in danger of immediate extinction. Even a strong wind, which is common at the site, could topple a patio wall." [75] Riddell suggested immediate legal action against Rasmussen, predicting that the contractor would be "awarded a judgment in his case now pending decision." The Chief Architect was correct in his assumption; the contractors won the appeal. [76]

But the government was hardly willing to concede the case, nor could it afford to absorb such a financial loss. The park used its new proof of structural deficiencies to request a revised settlement. Finally, in August 1964, the Board of Contract Appeals conceded that certain delays and deficiencies were the responsibility of the Rasmussen Company and divided the costs between client and contractor. Throughout this process, Park Service officials continued to perform structural tests; Chief Engineer H. G. Gibbs examined the foundations, and WODC Structural Engineer Lada Kucera analyzed the steel reinforcing. [77] Both mendiscovered problems. In a letter of September 9, 1964, the department counsel asked for a reconsideration of the matter after WODC engineers reported "serious structural damage" in Rasmussen buildings. [78] The government does not appear to have received additional compensation for the problems, which demanded immediate attention and continued management.

The Park Service had gathered extensive evidence of deficiencies in the construction of the Painted Desert for use in the lawsuit and, in the midst of the controversy, began to accept bids for repairing "structural defects in residences at Painted Desert Community." By March 1964, the park was already planning extensive repairs, including remodeling the carports into garages. [79] This work, essentially closing the open shelters with concrete block walls, was not actually begun until about four years later. By then damage had progressed enough to require more radical solutions than patching and plastering. Superintendent Donald A. Drayton took pictures of the damage after the summer rainy season in 1968 and sent them to the regional director along with a plea for help. Even after considering suggestions by Riddell and his office, the Superintendent believed "phased replacement and relocation" of the residences the most viable option. One suggestion from the design office involved a method of surfacing the area around the buildings to prevent moisture from sinking in. However, Dr. Rush, a consultant and geology professor at Northern Arizona University, told Drayton that when bentonite soils were covered in such a way, "a natural moisture pumping action is created," actually drawing the moisture from the outside into the bentonite foundation. After examining the site in 1971, Dames and Moore, consultants in applied earth science, found "no feasible solution to the problem" and predicted that the buildings would eventually have to be abandoned. Five years earlier, Dames and Moore had analyzed the adverse movement caused by the bentonite foundation at the Quarry Visitor Center, Dinosaur National Monument.

In 1973, Superintendent Charles A. Veitl announced changes in the visitor center, "implemented in order to achieve a standard of acceptance more in line with those outlined in the Activity Standards Handbook." These choices would also adjust the focus of interpretation from the country's national parks to the immediate Petrified Forest environment. First, the map locating every national park was replaced by exhibits of petrified wood. Wall panels describing the entire national park system were substituted with a series of illuminated views of sites throughout the park. These were accompanied by exhibit cases containing items from each featured site. The room was carpeted "to obtain a better, more 'lively' appearance and create an atmosphere . . . more conducive to interpretation." When visitation was particularly heavy, Park Service personnel could use a portable desk for souvenir sales, thus leaving the information table for its instructional purpose. Planning for the most significant alteration—the addition of an auditorium to the far end of the visitor center—began in November 1974. The park's orientation movie had been previously shown in the community building. Auditorium "Plan B" was accepted in April and approved working drawings by mid-summer. The construction drawings completed in June show a new end wall erected in the lobby, shortening the space by about one-third. Auditorium equipment, including the projection booth, appears to have been installed in the storage closets. [80] In 1979 a new front entrance vestibule was constructed. As built, the front facade of the visitor center featured floor-to-ceiling windows and glass double doors facing the parking lot. Today, visitors enter from the courtyard side and pass through the original front door to reach the lobby. The glassed-in entrance vestibule was intended to conserve energy and "to improve foot traffic control," but it also minimizes the focus on the visitor center building. [81] Whereas visitors originally saw only the doors to the visitor center as they approached the complex, in 2000 the entrance to the Fred Harvey building is more prominent. [82]

In March 1976, Superintendent David B. Ames requested that Fred Harvey, Inc., conform to the park's new color scheme. By June, all buildings were to be painted "cliff brown" with "tobacco brown" trim, including the Texaco station. [83] During the spring and summer of 1977 the park made further "improvements," reroofing the buildings and quarters and rehabilitating the houses. Citing lack of insulation as a problem during the winter, the park installed a Franklin stove in one unit as a test until further funds were approved. Carpeting was added both for insulation and to cover the linoleum floors cracked due to the moving bentonite foundation.

In 2000, the plan of the Painted Desert Community remains much as it was in 1963. All of the buildings are extant and the general circulation pattern remains intact. However, since the 1960s, changes have been made that, when taken together, significantly alter the aesthetics of the place. Although much of the remodeling was done to repair faulty construction, the methods of solving structural problems often evolved into aesthetic issues. For example, perhaps in an effort to cut down on glare, residential strip windows extending from wall to wall were reduced to standard rectangular windows. These rooms were once illuminated by a dramatic stripe of light; today, they are dark and oppressive. The open mudrooms, left unroofed so that laundry would dry quickly, are now covered over; if useful for storage, the enclosures diminish patio space and block additional light. Flat roofs—once the unifying feature of the entire complex—are now sometimes slanting, sometimes raised in zigzag profile. Flimsy metal rods with curling decorations have replaced the smooth metal poles supporting the covered walkways in front of the residences. The community building's aluminum roll down door has disappeared, leaving featureless wall in its place. Wood paneling covers much of the Fred Harvey building's once shimmering glass wall. One of the tiled columns is actually enclosed within a courtyard entrance vestibule. Although many of these alterations clearly originated out of functional needs, such as drainage and sun and wind protection, the chosen solutions also incorporated the aesthetic preferences of the day. In other circumstances, such decisions would hardly be worthy of mention, but at the Painted Desert Community, where every element reinforces a modernist aesthetic, these "domesticating" alterations might as well be Queen Anne turrets or classical pediments.