|

National Park Service

MISSION 66 VISITOR CENTERS The History of a Building Type |

|

CHAPTER 5

Administration Building

(Headquarters; Beaver Meadows Visitor Center)

Rocky Mountain National Park, Estes Park,

Colorado

On Friday July 16, 1965, Rocky Mountain National Park celebrated its fiftieth anniversary with the dedication of the Alpine Visitor Center at Fall River Pass, the first Mission 66 visitor center constructed in the park. [1] The location of the building was more impressive than its architecture. Visitors climbed Trail Ridge Road, the country's highest continuous highway, and were suddenly confronted with a modern visitor center in the forbidding tundra landscape 11,796 feet above sea level. Built of stone and concrete, with a shingled gabled roof and log beams, the simple building featured a glassed-in viewing area overlooking Chapin Creek and the Mummy Range. After the grand opening celebration, participants traveled back down the road and gathered at Beaver Meadows for an afternoon ground-breaking ceremony. The site was a meadow just up the hill from the utility area along the new road to the Beaver Meadows entrance station. George B. Hartzog, Jr., director of the National Park Service, local dignitaries, and Charles Gordon Lee of Taliesin Associated Architects witnessed Colorado Congressman Wayne Aspinall dig a few shovelfuls of dirt in honor of the future Administration Building. [2] Although Mission 66 officially concluded the next year, the development campaign it inspired continued until the end of the decade at Rocky Mountain with the construction of the Administration Building, commonly known as the Headquarters (1965-1967) at Beaver Meadows and the West Side Administration Building (1967-1968, later Kawuneeche Visitor Center) near Grand Lake. Together, these visitor centers represent the culmination of a decade of planning and designing modern visitor facilities. As one of the final buildings by a private firm, the Headquarters demonstrates the Park Service's continued eagerness to experiment with modern architecture in the parks and to engage in risky collaboration with well-known modernist designers. The Park Service commissioned Taliesin Associated Architects, Ltd., to design the Headquarters at Beaver Meadows, knowing that these devoted followers of Frank Lloyd Wright could only design an exceptional building.

Rocky Mountain drafted its Mission 66 planning prospectus in 1956 amid the excitement of a 320-acre park boundary extension and news of a new eastern approach road. [3] President Eisenhower authorized the addition to the eastern park boundary in June. The two-and-a-third mile approach road, a project first conceived in 1932, connected State Highway 262 with Trail Ridge Road, traversing an area known as Beaver Meadows. According to this plan, the new visitor center would be located on undeveloped land in Lone Pine Meadow just below the turnoff for Moraine Park. Park Service designers envisioned a "principal visitor center" adjacent the new road with facilities for both visitors and staff. The building was to house interpretive exhibits, an enclosed, glassed-in observation porch, and the information/orientation services currently handled at the entrance station. Indoor and outdoor auditoriums would supplement the museum interpretation. The cost of the new visitor center was estimated at $200,000. [4] This initial Mission 66 development proposal also included provisions for the expansion of a one-room facility at Fall River Pass jointly owned by a concessioner and the park. Thousands of people stopped in this area every day, but the building could only accommodate thirty at most. A new facility would provide concessions and interpretation relevant to the alpine setting. On the west side, similar services would be offered at "Grand Lake Visitor Center." Trailers equipped with information and exhibits were stationed at Rainbow Curve on Trail Ridge Road and Lake Granby Overlook off Highway 34 to determine the value of permanent visitor facilities in these areas. [5]

By 1958, planners were considering several alternatives for park development, all of which anticipated major changes in roads and traffic patterns around the eastern entrance. One possibility was a visitor center at Deer Ridge near the convergence of Highways 34 and 36. Since the Beaver Meadows entrance and the Fall River entrance guarded these primary access roads into the park, a visitor center between the two would serve the greatest number of visitors. However, because the chosen site included several inholdings, such as the Schubert family's popular Deer Ridge Chalet, acquisition of the property before the conclusion of Mission 66 was doubtful. A description of the proposed building mentioned standard visitor center components: a lobby, exhibit space, and audio-visual room. Significant architectural features included an elevated penthouse and viewing terraces, both of which related to the interpretation of glacial geology. In this scenario, the park headquarters building was to be located near the utility area, south of High Drive, and devoted exclusively to park administration. In the interim before the Deer Ridge Visitor Center was completed, visitor services could be offered from a nearby auditorium building. Although this plan was not adopted, efforts to acquire the desired property were eventually successful. [6]

A more expedient alternative, considering the land ownership situation, was the construction of a visitor center building at Lone Pine, the site suggested two years earlier. This proposal described a 10,200-square-foot building for visitor facilities, which included an optional auditorium and naturalist's operating headquarters and workshop. A headquarters for administrative functions was planned about a mile down the road. At this time, planners imagined the administration building in conjunction with the utility area and distinct from anything having to do with visitors or interpretation. This "master plan development outline" was reviewed by Lyle Bennett, WODC architect, and recommended by Chief of Design and Construction Thomas Vint in 1958. During the master planning process, the park was also considering a visitor center at the Grand Lake entrance. In April 1958, Cecil Doty submitted a prototypical Mission 66 design for what would later become known as both the West Side and Kawuneeche Visitor Center. The most prominent feature of the proposed wood frame building was a flagstone porch; the restrooms on the left side of the building extended to the edge of the porch, while an administration wing on the right was flush to the lobby entrance. Porch flagstones continued inside the lobby. Directly behind the lobby was an audio-visual room and to the left, an exhibit room. The visitor center constructed nearly ten years later would only resemble Doty's drawing in its adherence to programmatic requirements. [7]

The new eastern approach road opened in 1959 but the Thompson River entrance remained in use until 1960, when the Bear Lake cut-off was completed and the old entrance closed. Park planners predicted that the new entrance would result in increased use of the Moraine Museum, a former lodge constructed in the early 1920s. The museum's centralized site was viewed as more important than the rustic building, which could "be razed and replaced by a modern, fireproof structure with space-heating for all-year operation if required." In its place, the park envisioned a two-room exhibit facility, an overlook porch equipped with audio-visual equipment, a lobby and information desk, restrooms, and a few small offices. Although the Moraine Museum was spared, as Mission 66 planning progressed, the Park Service increased efforts to acquire inholdings, remove old buildings, and restore the natural landscape as much as possible. Between 1958 and 1962, the park purchased Fern Lake, Bear Lake, and Spragues Lodges; two private "guest ranches," the Fall River Lodge in Horseshoe Park and the Brinwood Hotel in Moraine Park; and the Stead Ranch at Moraine Park, site of the Deer Ridge Chalet. [8] The buildings were demolished in the name of wilderness conservation, but many Estes Park residents and seasonal visitors lamented the loss of favorite vacation resorts. To complicate matters, the park's environmental preservation efforts were carried out just a few years after a controversial new ski facility opened at Hidden Valley. In light of the effort to remove private development and thereby enhance the natural surroundings, the Park Service ski concession was questioned by both locals and environmentalists.

While other parks upgraded concessioner facilities inside their boundaries, Rocky Mountain was able to take advantage of its proximity to Estes Park for visitor accommodations and most services. This close relationship between the park and the town dated back to the park's founding in 1915, when a rented downtown building became the first headquarters. In 1921, the Estes Park Women's Club resolved to loan a parcel of land in town to the park, and once an act of Congress passed the bill, a superintendent's office was constructed on the city lot about three miles from the park boundary. [9] During the Mission 66 development and planning process, maintaining good relations with the town was of considerable importance. Superintendent Granville Liles understood that the design of the new visitor center should reflect the close ties between the park and the community of Estes Park.

During the first four years of Mission 66, Rocky Mountain spent over three million dollars on improvements, but had seemingly little to show for it; a large portion of the budget went towards "invisible" repairs, such as updating sewage and water systems. The summer of 1960 brought the first Mission 66 structure, the Beaver Meadows Entrance Station, as well as enlarged campgrounds at Endovalley and Glacier Basin, complete with "lecture amphitheaters." [10] Road repairs, turn-outs, and additional roads were under construction. But the featured visitor centers existed only on paper, as Park Service architects and planners continued to discuss visitor circulation, building location, and other issues crucial to the park's preservation and use.

The earliest extant graphic representation of the proposed east side "Administration and Visitor Orientation Building" is a November 1962 site plan by the Midwest Regional Office. [11] The drawing shows a building shaped like an angular polywog, its head to the west and crooked tail behind. Visitor parking is located on the south side, visitors entered the "head" of the building, and employee parking is provided in the rear adjacent to a central service yard. Because the road separates the new building from the utility area, the scheme did not allow efficient traffic flow. In an effort to remedy this problem, the office drafted a revised plan with a bridge over the entrance road linking the visitor center, to the south, with an administration building on the north side. The next month, a third scheme reunited the two functions in a U-shaped plan south of the entrance road, the side adjacent the utility area. The lobby and auditorium were located at the front and formed the widest section, with narrower central and eastern administration wings. Parking was divided—visitors in front of the building and employees on the east side. During this preliminary design phase, Cecil Doty drew elevations and plans for his version of the future administration building. [12]

Although the "pre-preliminary designs" Doty produced in February 1963 hardly resemble the final building, they anticipate several of its main qualities. The entrance facade of Doty's Administration Building features a single-story office wing, with a double-height auditorium and lobby on one end balanced by the south wall of an additional two-story office wing on the other. Employee parking is on the west side, and from this vantage point, the building appears to be two stories. Visitor services are located in the east end of the building, a segregation of visitor center and administrative functions that foreshadows Taliesin's treatment of visitor and employee use. On the exterior of his administration building, Doty imagined "cement block, stucco and precast panels with heavy exposed aggregate." The office windows were a seemingly continuous strip of glass with thin metal mullions spaced every four feet, and roofs were flat. The Doty scheme was dominated by its extensive office wing and might have seemed equally appropriate in either an industrial or wilderness park.

The park and WODC were not willing to accept Doty's plans without exploring additional possibilities for the new building. In April 1963, a Park Service architect named Roberson produced an "advance study plan for review and adjustment." This simple line drawing shows the first and second floors, and, in general outline, resembles the "polywog" plan of two months earlier. A partition separates the audio-visual auditorium from a lobby and exhibit space which together form roughly an oval shape. The administrative offices are arranged on either side of a corridor that emerges from the rear of the lobby. This 110-foot wing is joined to a 96-foot wing angled slightly towards the front of the building. Although the drawing is crude and the plan awkward, the general organization of spaces and hierarchy of services foreshadow those of the constructed building. During this time the facility came to be known as the administration or administration-orientation building (in the Headquarters area), perhaps to distinguish it from previous schemes involving two separate buildings. [13]

Park Service personnel were still discussing the building's location in February 1964. That summer, William Wesley Peters and Edmund Thomas Casey of Taliesin Associated Architects visited the park to examine potential sites. [14] According to Casey, the firm was contacted by Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall regarding design of a future Rocky Mountain Park headquarters. [15] The basic programmatic requirements were outlined by Superintendent Liles, and Taliesin was asked for advice regarding the building site. As resident landscape architect Richard Strait recalls, the park staff had focused the search for an appropriate visitor center site on Horseshoe Park or Deer Ridge, the site of the controversial private lodge and cabins. [16] Both sites posed circulation problems, however, and the cramped spaces were considered inadequate. Strait and the park planners preferred a building on the north side of the road, which would provide better traffic flow. When Casey arrived, the choice had been narrowed down to two locations, the one ultimately selected and another about a mile further into the park on the north side of the road. The latter site was finally rejected as less conveniently situated in relation to the residential area, and therefore a potential source of traffic problems. At the lower hillside site, the architects could envision a better segregation of visitors and administrative facilities. Although Strait and the park staff were not eager to build "on the wrong side of the road," they agreed that this was the best solution considering the many issues involved. In combination with the building's unusual design, these early planning studies gave rise to rumors that the two-story south facade, as eventually built, had been originally designed to face north. In fact, the building was designed and built specifically for the hillside site it occupies. [17]

During these early discussions, Casey remembers the superintendent's eagerness to improve the relationship between the park and the town of Estes Park. The superintendent hoped that a new headquarters closer to town might reduce some of the tension caused by the park's policy toward inholdings. As primary representative of the client, Liles not only influenced the location of the building, but also the development of its program. His hope that the auditorium might be used for city council meetings and other civic events materialized in the form of a larger theater space that included a cozy fireplace. In September 1964, the Estes Park Trail announced that, after five years of planning, the park had finally chosen a site for the building "such that it will serve visitors of the Estes Park area without requiring them to enter the National Park itself." [18] Rocky Mountain was one of the few parks that chose to build a Mission 66 visitor center outside its official entrance, enabling visitors to use the building without passing through a gate or paying a fee.

Frank Lloyd Wright and Taliesin

Associated Architects, Ltd.

When Secretary of the Interior Udall called on Taliesin Associated Architects in 1964, the firm's founder, Frank Lloyd Wright, had been dead for five years. The most influential American architect of the 20th century, Wright left behind an architectural legacy unsurpassed in its range and influence—from homes on the prairie to urban office buildings, Southern California residences to New York's Guggenheim Museum. Wright inspired generations of modern architects to design buildings sensitive to site, climate, and regional associations. He taught countless young designers by example, through his built work, but also at the Taliesin Fellowship, the architecture school he founded in 1932. During his career, Wright incorporated history, art, poetry, music, and whimsy into designs for about a thousand buildings. Perhaps more effectively than any architect in the world, he achieved the delicate balance between contemporary innovations and centuries of tradition.

Wright built the house he called Taliesin in 1911 on family property in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Taliesin means "shining brow" in Welsh and refers to the siting of the building on the brow of a hill. For Wright, whose mother was Welsh, the name also invoked Taliesin, the legendary bard of Welsh folklore. Taliesin stood on the brow of a hill near the Hillside Home School, an institution Wright had designed for two aunts nearly ten years before. Early life in the house was a series of tragedies: two fires, the murder of Wright's mistress, and an unhappy second marriage that almost cost him the homestead. Finally, in 1928, Wright brought his third wife, daughter and step-daughter to live at Taliesin. As the country entered the Depression, Frank and Olgivanna Wright found themselves with "everything but money," and turned to the employment that had sustained the two spinster aunts. The school they established, the Taliesin Fellowship, occupied the remodeled quarters of the Hillside Home School and adopted the aunts' radical educational philosophy of learning through hands-on experience. Among the applicants for enrollment when the school first opened in 1932 was William Wesley Peters, who would go on to marry Wright's adopted daughter and become the principal of Taliesin Associated Architects. As Peters and his fellow apprentices soon learned, membership in the fellowship involved more than mastering lessons at the drafting table. Apprentices were expected to perform manual labor around the farm, prepare meals, and engage in other tasks necessary for the maintenance of the school. They also participated in social events, such as a daily tea and periodic celebrations requiring exotic costumes and often exhausting preparations.

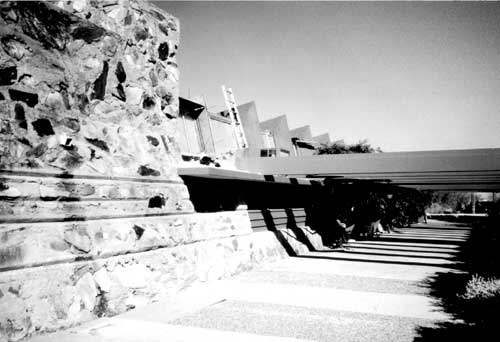

The fellowship life of daily chores, architectural instruction, and social events was broadened in 1937-38, when Wright began planning a branch of his school in Arizona. Taliesin West was inspired by a temporary desert camp called Ocatilla that Wright had designed in 1929 while working on a project for a resort in Chandler, Arizona. Once the complex was under construction in 1938, the fellowship migrated between the two locations, living in lush Midwestern farmland during the hot summer months and in the temperate desert through the winter. This seasonal routine of dramatic environmental contrasts suited Wright personally. He expressed this satisfaction in the architecture of the schools, both of which were constantly altered and remodeled as inspiration and reason demanded. [19] The intense life of the fellowship, with it hands-on training and rigorous social obligations, imbued devoted students with the design philosophy, if not ability, of their mentor. The Taliesin apprentices who worked on the Rocky Mountains Headquarters not only learned from Wright's method, but also from their experience at his desert retreat, Taliesin West.

Wright established the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 1940 to guarantee that his "intellectual property" would remain within the fellowship. Upon his death in 1959, this governing body became responsible for the future organization of the school. The core of loyal apprentices, or senior fellows, who decided to carry on Wright's work, were organized as Taliesin Associated Architects. Although maintaining the Taliesin farm proved to be more then it could handle, the architectural firm remained committed to the "learning by doing" philosophy so important to Frank Lloyd Wright. The Foundation established standards for a new school, the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, and received its professional accreditation in 1996. Wright's belief in the apprenticeship system was carried on through a close relationship between the architectural firm and the school, which share a single drafting room and a dedication to Wrightian design principles. [20] Students work for the firm as part of their learning experience. The school continues the traditional annual migration between Scottsdale and Spring Green. In 2000, Taliesin Associated Architects maintains these two offices, as well as offices in Madison, Wisconsin, Bradenton, Florida, and Hermitage, Tennessee. Eight of the fourteen principles remember life under Wright, and most were exposed to the philosophy of his chief apprentice, William Wesley Peters. [21]

Figure 54. Taliesin West, Scottsdale, Arizona, 1998. (Photo by author.) |

After the loss of their mentor, the senior fellows looked to Wes Peters for leadership. As managing principal of Taliesin Associated Architects, Peters was responsible for overseeing all projects and, at Wright's death, that meant completing unfinished work. Project architect Tom Casey recalls counting eighty-five ongoing projects, including the Guggenheim Museum, Beth Shalom Synagogue, and Marin County Center. Wright's continuing legacy is perhaps best illustrated by Monona Terrace, a lakeside convention building and community center on axis with the state capitol building in Madison, Wisconsin. The commission came to Wright's drawing board in 1938, and, with the help of the apprentices, he revised the complex several times over the next thirty years; the convention building was finally completed by Taliesin Associated Architects in 1997. By the early sixties, the architectural firm was not only continuing work begun during Wright's lifetime, but taking on new commissions as well. [22]

Taliesin Associated Architects received the headquarters building contract July 1, 1964, just a few weeks after the preliminary site visit. Over the next few months, Peters and Casey met with park architects and planners to discuss the project. At a meeting on September 24 WODC Chief Sanford Hill, John Cabot, chief architect of the Washington office, and architect Jerry Riddell discussed the proposed building with Taliesin and agreed on a schedule for completing the plans. The park staff was already reviewing "revisions of the floor plan requirements for the new Headquarters Administration Building," and by the next month they were examining preliminary drawings and submitting comments to the regional director. In-house architects were involved in floor plan revisions.

When local papers learned that Taliesin Associated Architects would be designing the new headquarters, stories began to appear about Frank Lloyd Wright's previous commission for a hotel in the park. According to the Estes Park Trail and the Rocky Mountain News, Wright designed the Horseshoe Inn for W. H. Ashton, who operated the hotel until 1915. [23] The Park Service purchased the building from new owners in 1932 specifically to destroy it. Reporters couldn't resist mentioning the demolished Horseshoe Inn as a precedent Frank Lloyd Wright building. In fact, Wright's design for an expensive luxury hotel with room for a hundred guests is a formal complex of buildings that bears little resemblance to the two-story wood frame structure actually constructed. The front page of the 1908 Estes Park Mountaineer featured the design by "Frank Lloyd Wright, the famous architect of Chicago." The building's Wrightian characteristics are apparent in the accompanying description:

The scheme of the building is a large dining room and living room, separated only by a wide chimney with a large fireplace on both sides. Around the two rooms will be a balcony looking down into these rooms. From these two rooms, which form the central part of the building, wings will run both ways, ending in towers two stories high. The guest rooms will be in the wings, and all will have large windows commanding a view of the mountains. One of the wings will span a little stream, and the music of the waters splashing over the rocks beneath the window, ought to lull to rest the tired tourist after a day of mountain climbing. The ground between the main building and towers at the end of the wings will be made into an open court, and in pleasant weather will be used as an outdoor dining room. [24]

The emphasis on a central hearth, the split level arrangement, and segregation of community spaces and guest rooms in this proposed design are typical of Wright's work. Throughout his career, Wright used ceiling heights to distinguish between intimate spaces and expansive, double-height gathering places, such as theaters or living rooms. Open courts become outdoor rooms, and indoors appears to flow outside. If only in project form, the Horseshoe Inn suggests Wright was thinking about natural water features entering the building site as early as 1908. [25] Unfortunately, the hotel known as Horseshoe Inn, as built, had nothing to do with Wright's design.

Designing the Headquarters:

Four Important Points

Regardless of Wright's reputation for previous work in the area, Taliesin Associated Architects was known for carrying on his tradition of "Organic Architecture," the design of buildings closely related to the landscape. The firm's reputation for environmentally sensitive modern architecture attracted the attention of Mission 66 planners. When the commission was accepted, Tom Casey was assigned the position of project architect. Casey designed and supervised the building from concept through completion, as was the firm's standard practice. In an interview, Casey used "four points" to explain how Wright's philosophy influenced the design of the Headquarters. [26] First, the building had to appear part of the site and not merely sit upon the land. Second, methods of structural manipulation were employed to destroy the traditional "box" characteristic of so much American architecture. Third, materials would be chosen for the effects of weathering over time so that they might reveal their true nature. And finally, if the building were to represent American architecture, it must somehow symbolize democracy. Like Le Corbusier's famous "five points," these four points were intended to simplify Wright's complex and continually changing design philosophy into terms the public could understand. Taliesin developed this summary of Wright's teachings in the early 1980s, when the firm was preparing a traveling exhibit of his work called In the Realm of Ideas. Although Wright himself never distilled his philosophy in this way, this concise formula helps to explain certain aspects of the headquarters design.

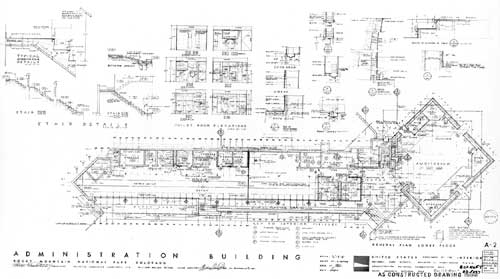

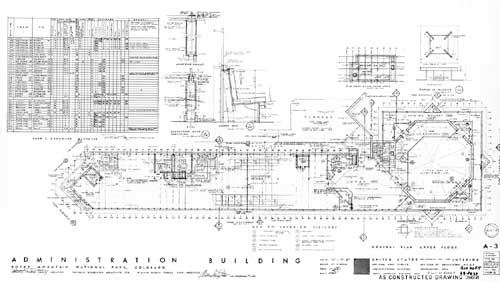

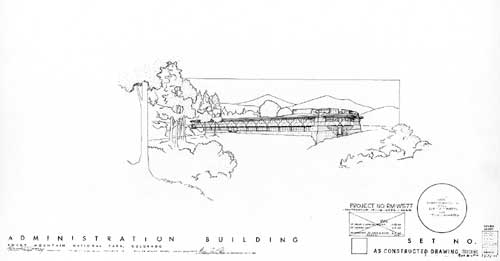

Figure 55. This sketch of the front elevation of the Headquarters served as a cover sheet for the set of "as constructed" drawings completed in March 1967. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

In plan, the building Casey designed resembles several of the early Park Service schemes: it consists of a long corridor of administrative offices attached to a larger room housing featured visitor services. The box is "burst" by a triangular conclusion to the administration wing and the 45-degree rotation of the auditorium, which results in an unusual lobby space. The building is sited "in the land" so that the transition from the upper to the lower floor is hardly noticeable. And yet employees entering from the rear perceive the building as two stories. This level change and the organization of spaces effectively separates visitors from park staff without requiring prohibitive signs or resulting in confusion and unnecessary traffic in the staff area. [27] The transition from inside to outside is also emphasized using a variety of Wrightian methods. The entrance to the main lobby is low and dark, but opens into a lobby with a higher ceiling. Lights hidden behind the steel facia and natural lighting from a clerestory window on the west side enhance the contrast from low to high, dark to bright. These effects are also apparent in the office corridors, where oppressively low halls lead to offices with high ceilings and clerestory windows.

The third "point" of design, the nature of materials, is both the most obvious and the most complex. The disoriented visitor is likely to stumble inside without paying much attention to the variety and color of stones, their contrast with the bare concrete, or the pink paint under the eaves that matches mortar and sidewalk. But even the most oblivious might notice the unusual Cor-ten steel framework enveloping the second story of the building. The dynamic pattern wrapping around the building is built up in several layers, with thin steel sheets welded onto the thicker tubes that form the framework. The resulting abstract design, a series of rigid triangles said to have been derived from Indian rock art, reappears throughout the building—as interior ornament, in the angles of rooms, and other unexpected places. Steel trim is also a feature along the roof of the building, where it serves as a cornice and is embossed with a decorative pattern. This design is repeated in the pressed metal panels around the auditorium. If the roughness and redness of the stones is intended to blend with the surroundings, the steel ornament seems a deliberate effort to fight this tendency. Even the steel's deep reddish color fails to "naturalize" this sharp, industrial material. Whether the building is successful in its effort to satisfy the fourth point—to qualify as "democratic" architecture—is purely subjective. That the Headquarters was designed by architects, and intended to convey abstract meaning, however, is obvious.

In a general way, "the four points" can be observed in any Wrightian design. For the purposes of this study, however, comparative analysis is limited to the examples that the apprentices knew best: Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin. A quick glance at Taliesin West establishes its striking resemblance to the Headquarters building—the low profile, stone aggregate in cast concrete, and exposed structural system. The buildings draw attention to the landscape, both through siting and choice of material. Wright described Taliesin West as a ship, with its "concrete prow" facing south overlooking Paradise Valley and the Camelback Mountains. [28] The Headquarters also has a ship-like form, and during construction, the auditorium end was referred to as "the east prow of the Monitor." [29] Taliesin is surrounded by low walls and planters for cactus; the Headquarters uses similar low walls to define entrances and areas for plantings. A separate theater building, known as the kiva, stands on one corner of the Taliesin complex. Not coincidentally, the amphitheater at Rocky Mountain was said to resemble a ceremonial kiva, though probably more in its association with the Taliesin building than an authentic Southwestern Indian dwelling. The symbol for Taliesin Fellowship, an interlocking square spiral, was an adaptation of a prehistoric pictograph discovered near the Ocatilla camp. [30] According to Wright, "inspiration for Taliesin West came from the same source as the early American primitives and there are certain resemblances, but not influences." [31] The ceiling of the drafting room at Taliesin in Spring Green is decorated with a pattern of jagged triangles protruding from wood trusses, much like the triangular ornament featured throughout the Headquarters. The ornament used in the Headquarters may have had its closest antecedents in the Fellowship's own design vocabulary.

Building the

Headquarters

In March 1965 Superintendent Liles met with Regional Director Garrison, staff members, and Casey to review the building's working drawings and overall construction program. As on-site "architects' representative," Taliesin selected Charles Gordon Lee, a former apprentice who had established private practice in Denver. [32] The bidding process for the construction of the Headquarters began with notices advertising the "partly reinforced concrete and partly structural steel frame" building, and a May 24 press release invited potential contractors to obtain copies of plans, specifications and a photograph showing "an artist's conception" of the building. [33] Gordon Lee and WODC staff attended a June 17 "pre-bid conference" for construction companies interested in the project. Five days later, Kunz Construction Company of Arvada, Colorado, submitted the lowest bid of $652,871.95. The ground-breaking ceremony took place on July 16, and the Park Service issued a "start work order" the next week. [34] Shortly after, Liles transferred to a different park and was replaced by Superintendent Fred J. Novak.

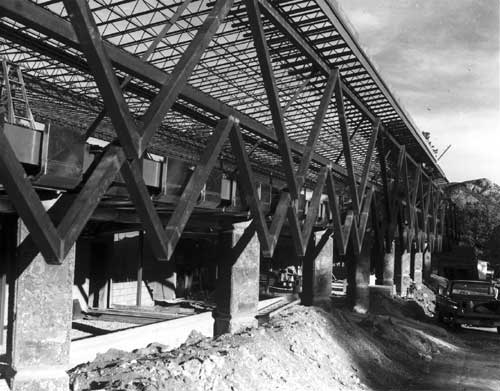

Figure 58. The concrete and stone panels were cast on the site and lifted into place by crane, November 1965. (Photo by Miller. Courtesy Rocky Mountain National Park archives.) |

The Headquarters' unique materials and construction required all sorts of special provisions, not to mention the use of building techniques unfamiliar to most contractors. Monthly superintendent's reports and Park Service snapshots (by WODC architect Jerry Riddell) capture the drama of the construction process, as cranes lifted the heavy walls into place. The concrete and stone walls were a puzzle of one hundred and one pre-cast concrete panels in sixty-four different sizes, one of which weighed 65,000 pounds. The challenge was to fit each panel into its proper location. In April, "the contractor was advised to correct the alignment of a concrete column consisting of panels PC/3-4-5," which was "out of plumb by 4 1/2"." [35] Even such a slight maladjustment could result in a serious structural problem and required immediate correction. Sections were cast in wooden forms assembled on-site; large stones were placed in the forms, concrete was poured around them, and then pebbles—or gravel aggregate—were sprinkled on the exposed wet mortar. This method of creating a "naturalistic" wall originated during the construction of Taliesin West in 1937-1939, when Wright was searching for a method of building with regional stones that could not be cut easily like granite or limestone. [36] "Face rocks" were selected for flat surfaces, thickness, and color. These were set into wood frames along with smaller stones, or "rubble," to hold them in place while a mixture of concrete and sand was used to fill the crevices. [37] By varying the size of the stones and laying them in rough horizontal rows, Wright created the illusion of cut-stone masonry. At the Headquarters, auditorium panels included electrical wires and other utilities imbedded in concrete along with the stones. Once the concrete hardened, the panels appeared to be composed of natural stone, but the seams between panels were also a visible design element, creating both horizontal striations resembling geologic strata and a sense of the building's structure. According to former apprentice Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, the horizontal concrete lines also originated in the Arizona desert and were perfected at Taliesin West. He recalls

. . . An outing the Fellowship made to northern Arizona into one of the canyons which had once been under water, the deep, horizontal grooves in the stone canyon walls caused by water erosion greatly appealed to Mr. Wright. On his return to camp he instructed the apprentices building the walls to insert triangular strips of wood stretching in thin lines on the inside surface of the wooden forms prior to placing stones and pouring concrete. When the forms were removed the indentation of the horizontal strips left an impression within the concrete surface of the wall, creating yet another element with which the sun could make deep shadow lines across the mosaic wall. [38]

At the Headquarters, the use of lichen-covered pink fieldstone from the nearby town of Lyons heightened the ornamental effects. As Tom Casey remembers, the stone had been left in an abandoned quarry established by the government for use in Denver's first federal courthouse. The architects were delighted to find leftover red sandstone the thickness of stairs, now suitably weathered and broken into smaller chunks. They had only to gather the stone and haul it to the site. [39]

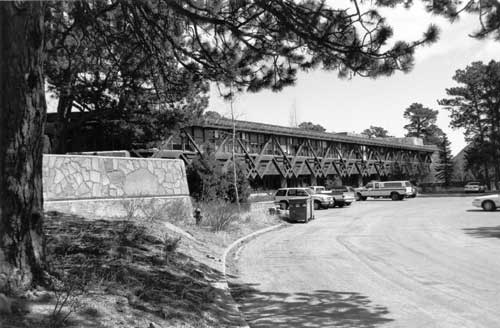

Figure 59. The building's steel framework, as seen under construction in January 1966. (Photo by Lockwood. Courtesy Rocky Mountain National Park archives.) |

The November 18, 1966, Estes Park Trail announced that the Headquarters employed a "structural steel truss system" on the second floor. The architects called this dynamic and complex pattern of triangles, formed of hollow steel tubes and thin metal sheets, "architecturally exposed bare structural steel." Sections of tubes were welded together to form the triangular skeleton of the design and the Cor-ten steel welded to either side. Steel-stamped spandrel panels were attached directly to the exterior walls. A similar stamped sheet metal facia encircled the edge of the roof. This complicated mixture of structure and surface ornament proved to be one of the most problematic aspects of the design. Taliesin had to special order the material as needed because the supplier, U. S. Steel, did not warehouse the required type and only manufactured it in one mill. The steel was blasted to a white hot state to achieve the desired color effect, which required allowing the material to oxidize (rust) for a period of one to two years. Cor-ten, high carbon steel, was a new, self-sealing product that never required painting. [40] The designers chose Cor-ten both for its low maintenance and for its rich color, which worked with the desired earth tone palette and the surrounding environment. The steel typically rusted to a warm purple in the city, but at high altitudes without excessive pollutants, it turned a deep brown. In its final aged state, the steel was said to resemble tree bark. One of U. S. Steel's promotional ads includes a photograph of the Headquarters next to a tree with the caption, "this building is painting itself!" Despite pressure from the design office in Washington, D.C., slow production of the steel resulted in construction delays. [41]

The Headquarters was half complete by January 11, 1966, when union officials from the Denver Building Trades visited the site to speak with James O'Shea, acting project supervisor. A Mr. Nilander and his partner asked questions about pay rates, overtime wages, subcontractors and job classifications, promising to continue their interrogation the next week. Although they did not return, a picket line of employees from Sheet Metal Workers Local #9 formed near the site on January 17. Park Service officials met with union representatives and learned that the problem lay with the contractors handling the heating and air conditioning systems. For some time, the union had been picketing all projects associated with Croy Brothers Heating and Air Conditioning, Inc. The steel workers, plumbers and electricians chose not to cross the line for a few days, but arrangements were made with their respective unions to allow the resumption of work. At the time, the incident caused little more than an unanticipated delay, but in retrospect, it foreshadowed a history of serious deficiencies in the building's air circulation systems. The lack of a typical forced air cooling system was specified by Superintendent Liles, who believed air conditioning an extravagance, particularly at over 7,000 feet. [42]

Over the next few months, the contractors placed concrete floors with terrazzo finish, installed window walls, completed electrical and plumbing work, and built up the roof installation. The pink terrazzo was laid with gold adonized aluminum seams, the colors carefully chosen to add warmth to the interior. Window casings were of steel obtained locally. In addition to the attention lavished on interior surfaces, the Taliesin apprentices employed a Wrightian technique of dividing interior space in their use of an elaborate partition system. The basic drawings of the first and second floors included only the permanent walls around utilities and bathrooms; the remainder of the building was left open space. Additional drawings specifically devoted to the interior partition system show the space divided into the chosen office arrangement. The typical office partitions were gypsum board with a corrugated paper core. Anodized aluminum studs stretched the height of the walls about every four feet. The upper few feet of most partitions were glass, sometimes filling a triangular space, with the gold aluminum continuing up to the ceiling as a mullion. Doors were red oak veneer but solid wood to the core. In some of the fancier offices, red oak wood panels covered the gypsum board. Although the walls give the impression of permanency, their potential for change adds to the flexibility of the plan, not to mention the "breaking of the box." Whether or not park employees were intended to move the walls frequently is unknown, but one current ranger did successfully re-configure his office space at a recent date. [43] Wright used the partition system in all of his office buildings, and Casey recalled such flexibility in the Sunday school at Wright's Greek Orthodox Church (1956) as well.

At the height of excitement over the Headquarters in the fall of 1966, architect Victor Hornbein met with the superintendent to discuss preliminary drawings for the new West Side Administration Building. Although superintendent's reports indicate that Hornbein's plans were approved and even admired, the extant facility (later named the Kawuneeche Visitor Center) appears to have been designed by the Park Service's San Francisco Planning and Service Center. It is unclear whether or not collaboration took place, but Hornbein's name never appears on the final drawings. In any case, the Park Service was intrigued by Hornbein's preliminary designs, and, perhaps, by the Wrightian aspect of his work. A Denver native, Hornbein was an advocate of Wright's principles and had written about his architecture. His work in the Denver area includes two buildings that exemplify a Wrightian range of design—the Frederick R. Ross Branch Library (1951) and the Boettcher Conservatory at Denver Botanic Gardens (1964 ). The library emphasizes horizontal lines in a colorful mixture of brick and glass, while the conservatory is a bubble of seemingly woven concrete that manages to appear appropriate in its garden setting. Having made a reputation for himself with local buildings, and a recent splash at the botanic garden, Hornbein was an exciting choice as architect of the park's final Mission 66 structure. [44]

Although considering the design of a third new visitor center, the superintendent was still occupied with a variety of issues at the Headquarters as the building entered its final months of construction. Park staff and members of Kunz Construction gathered in his office on May 3 to discuss defective road paving and problems with "ceiling lighting, air return, upper floor and fireplaces." [45] Taliesin did not take part in this meeting, perhaps because it resulted in some minor change orders relating to lighting, the buzzer system, relocation of the audiovisual control panel, and information desk alterations. By August 1966, the estimated completion date for the Headquarters was mid-September, but a "pre-final" inspection near the end of the month revealed two hundred and twelve items requiring attention. Nevertheless, the final inspection of the building took place on October 21. Approval was contingent on smoothing the uneven terrazzo floors in two rooms. Although "many deficiencies" remained, the Headquarters was accepted in November contingent on their correction. Park Service officials and staff began moving into the building at the end of the month. Kunz Construction was still fulfilling its part of the contract in early January, with minor repairs and alterations, which included modifying the heating system. Final payment on the building had not yet been made in April, as preparations were made for its dedication on June 24, 1967.

As the Headquarters' dedication approached, Park Service planners were busy with the design and construction of the West Side Administration Building. An excellent example of Mission 66 style and planning, the visitor center was organized according to a standardized visitor circulation pattern. Upon approaching from the parking lot, visitors were immediately confronted with the restrooms to the right and a path to the visitor center to the left. A natural stream flowed under the bridge between the restrooms and lobby. Inside, the lobby space featured a large information desk surrounded by items for sale and small exhibits, a map, and relief model. Exhibit and audio-visual rooms were envisioned as a future wing of the building, to be entered from the right side of the lobby. [46] In the interim, this space featured an outdoor patio and pool made by the stream. The lobby was discreetly connected to a rectangular administration wing hidden in the back along with employee parking. Although the visitor center has little in common with the Headquarters, both buildings are unabashedly modern and also manage to blend into their respective park environments. The West Side Administration Building drawings included a "design statement," declaring a desire to "reflect the vertical forms as found in the adjacent lodgepole forest," and noted the choice of "wood and stone materials throughout structure to relate to the natural environmental phenomenon at the area." The building's simple vertical wood framework is punctuated by floor-to-ceiling sections of glass.

The final work on the landscaping of the Headquarters began in the spring and continued through the building's dedication. The park's new resident landscape architect, James O'Shea, worked on the exterior lighting in May and June to produce field layouts and inspections. The west entrance road was staked and graded. O'Shea's other responsibilities included examining the building and concrete curbs. In August, the park issued a change order to insure exposed aggregate finish on the curb and gutters. Work on the planting plan for the Headquarters, which involved mapping the area and researching plant material, occupied O'Shea during the spring of 1967. He may have filled the three roof planters installed in the center of each side of the auditorium. [47] Despite progress with the landscaping, a few technical problems remained to be solved. The heating and air conditioning system installed by Croy Brothers was operating so poorly that a mechanical design company was recommended as a consultant for the firm.

Furnishing the

Headquarters

Throughout the construction process, the park interpretive staff consulted with the architects regarding "floor plans and space and furnishing requirements." Because of the limited space provided for exhibits, interpreters planned to install a large orientation map in the lobby. This relief model of the park was originally commissioned by Rainbow Pictures of Denver for its orientation movie. When the film was completed in October, the park purchased the map and installed it as a permanent fixture in the lobby. Visitors saw the model when they entered the lobby and again in the thirty-five minute movie, "Rocky Mountain National Park," which was shown several times a day. Together, the movie and model were to substitute for traditional exhibits in telling the "park story." [48] Before it was installed in the lobby, the model was repaired and adapted for interpretive use by Robert Miller, a Denver artist. Curatorial staff explored methods of lighting the model and projecting features on the relief, which was accurate to .025 of an inch. Labeling the model proved to be an equally serious matter for the division of Conservation, Interpretation and Use. It wasn't until April 1967, that staff finally chose two "backlighted 16" x 20" color transparencies with the place names on an overlay" from the K. R. Bunn Studio in Denver. Bunn was also commissioned to cast five "deck-size" relief models from the original for use at information counters throughout the park. The terrain model was considered important enough to list in the dedication program, along with participants in the construction of the building and the production of the orientation movie.

In February 1966, with the building a little more than half complete, Casey and Hill discussed their progress with the superintendent, assistant superintendent, members of their staff, Mott, and O'Shea. [49] Interior design and furnishings were the topic of the day and would continue to be an issue. After the meeting, Phil Romigh of the WODC was sent to Scottsdale to work with the Taliesin staff on interior decoration and related matters. Following in the tradition of their mentor, the firm not only planned chairs and tables, but coordinated upholstery and wood grain for just the right blend of colors and textures. The general plan of the upper floor included drawings of the simple plywood alcove seats and table. Elaborate faceted trash cans were also created especially for the Headquarters. Wright's widow, Olgivanna, was involved in the interior decoration and chose the red-orange color featured throughout the building. [50]

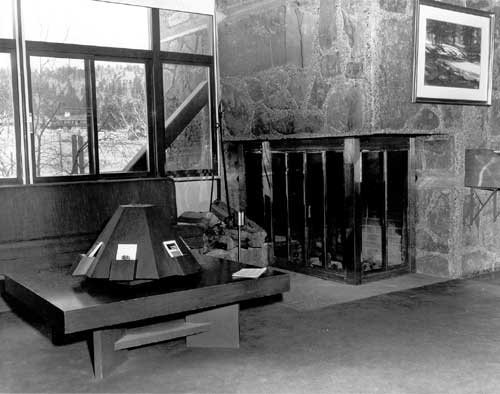

Figure 60. The original lobby included a fireplace and seating area to the right of the entrance. This view was taken in 1982, shortly before installation of the bookstore. (Photo by Walt Richards. Courtesy Rocky Mountain National Park archives.) |

The Park Service may have been surprised by the importance Taliesin attached to every aspect of interior design. This attention to detail certainly did nothing to speed up the furnishing process; delays were caused by such mundane matters as waiting for the arrival of wood samples for use in matching the wood furniture with the walls. Progress on the furnishing plan was again slowed in July, when the park learned that its request for furniture had been sent to the General Services Administration and that the work order remained unapproved. In September the park was finally told to purchase the auditorium chairs, conference table, guest chairs, executive chairs, secretary chairs, office table, sofa, and carpeting from Federal Supply. Literature describing the available furniture was sent to Taliesin. Bids for furnishing and installing drapes and sheer curtains and for the construction and installation of custom-made benches and tables were issued in mid-October. Highland Interiors was responsible for benches and tables, curtains, and drapes; Elmer's Case Company of Loveland, Colorado, produced forty upholstered benches with backs from Taliesin's designs at a price of $105.50 each. [51] The only exhibit in the building, the park relief map, was moved into the lobby in November. Staff began moving into the building that month, despite the lack of carpeting and customized furniture. The Roxbury Carpet Company, selected by Taliesin, was expected to provide carpet under the proper Federal Supply requirements, but not until March 31. Taliesin's selections of furniture from Federal Supply were scheduled to arrive in the interim, but the carpet, chairs, and benches were not delivered until April, just in time for four special performances of the Rocky Mountain film. The drapes were installed a few weeks before the park opened to the public. Five hundred people entered the lobby on May 30, and one hundred and eighty-six saw the movie. Interpretive services also included evening illustrated talks in the auditorium.

In May, the Estes Park Women's Club sent out invitations from the Estes Park Chamber of Commerce, Town of Estes Park, and National Park Service announcing the upcoming dedication of "the new Headquarters and Visitor Orientation Building." [52] About five hundred people attended the dedication of the Headquarters at 2:00 p.m., on Saturday, June 24, 1967. According to the superintendent, cloudy skies in Denver and Boulder "kept the attendance below what had been expected." As the Estes Park High School played a festive prelude, guests assembled in the Headquarters' parking lot. The Director of the Park Service, George Hartzog, Jr., served as master of ceremonies. Congressman Wayne Aspinall delivered the featured address, entitled "Past, Present and Future." The Estes Park Women's Club received an official "certificate of disclaimer," returning the property it had donated to the park in 1921. After the ribbon-cutting ceremony, visitors toured the building, viewed the film, listened to a string quartet from the Rocky Ridge Music Center, and enjoyed refreshments provided by the Estes Park Red Cross Canteen. [53]

The Visitor

Center

By the end of Mission 66, the programmatic design of visitor center buildings had become almost systematic—a series of required spaces gathered around the central lobby and viewing decks or large windows installed as dictated by the location. The rooms tended to be spacious, well-lit and functional. At the Headquarters building, Taliesin Associated Architects inserted an element of intrigue into the required formula. Visitors entered what appeared to be a single-story building through a low entrance. The center of the lobby space featured a higher ceiling emphasized by a pressed steel "cornice" similar to the exterior steel facia, which marked the transition from the lower section of the building to the central space. Depending on the time of day, the building could be quite dim. On the northwest side, a clerestory window cut into the raised area emitted natural light. Artificial lighting was hidden behind the steel cornice, creating a glowing effect as light bounced off the ceiling. Visitors were immediately confronted by the large relief map in the center of the room, and to its right, the information desk. Beyond was a wall of windows facing the Rocky Mountains.

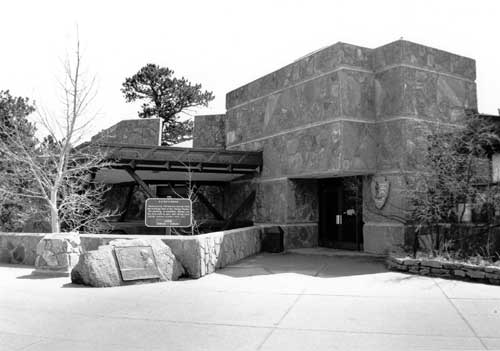

Figure 61. Rocky Mountain Headquarters, entrance, 1999. (Photo by author.) |

When the building was first opened, the space to the right of the entrance was an alcove lined with benches facing a stone fireplace. [54] This resting place was sparsely furnished with a coffee table, a few pictures, some reading material, and a guest register. The walls around the fireplace were left rough stone and concrete, but the facing wall was wood paneled. The alcove faced the information desk. A small space behind the desk was provided for the store, and sales were conducted from the information counter. On the left side of the lobby was a stairway down to the restrooms, apparently located in the basement. The auditorium to the left of the lobby was the main interpretive attraction. From the interior balcony, visitors could look down on the main auditorium, watch the movie, and walk out onto the viewing balcony encircling the auditorium. A door in the far southeast corner of the room led to the balcony, where visitors enjoyed a spectacular view of Long's Peak, the highest mountain in the park at 14,255 feet. The structural supports on the three sides of the open balcony, in plan the corners of the auditorium space itself, formed triangular spaces for dioramas. Although they appear in drawings and the spaces were built, the dioramas were never installed.

Figure 62. Rocky Mountain Headquarters, path from parking lot to entrance, 1999. (Courtesy National Park Service.) |

Before venturing downstairs to the restrooms and auditorium, visitors might not realize that the building is actually two stories. The stairway leading to the first floor is wood paneled and illuminated with lighting in the steps, which allows the rest of the space to remain dark in safety. As they come down the stairs, visitors are surprised to see natural light emanating from a wall of windows in front of them and a glass door leading to an exterior porch. To the left is the entrance to the auditorium and to the right, the restrooms. The low ceiling of the first floor landing becomes even lower upon entering the restroom area. A door in the vestibule between the men's and women's restrooms opens into the first-floor office wing.

Figure 63. Rocky Mountain Headquarters, service road and employee entrance, 1999. (Courtesy National Park Service.) |

The Headquarters is a very different place for park employees, most of whom enter the building from the rear. From this entrance, the facade is two stories with double walls of windows that expose the building's administrative function. Low stone walls, a stone planter, and boulders contribute to the landscaping, but this side of the building has an aura of efficiency. The primary entrance to the office wing is not the auditorium porch, but a central door opening into the main hall and facing the stairway. The first level contains museum offices and work spaces, while the upper floor accommodates administrators, the superintendent, and a conference room. On both levels the hallways have low ceilings that actually become lower in the center, like pitched ceilings turned inside out. In contrast, the offices are spacious and so full of light that special curtains are required. Customized light panels cover the entire ceiling of each office, adding a sculptural quality to the rooms. Although the offices were formed by movable partitions, the fine materials employed give the spaces an aura of permanency. From inside the office wing, the administrative function appears entirely separate from the visitor services; in practice, the public has easy access to the park offices and park employees can step out of the office wing into the visitor space in a moment.

Figure 64. The bookshop now occupies the original seating area, 1999. (Courtesy National Park Service.) |

In 2000, the visitor center appears much as it did upon its dedication in 1967, but elements of the visitor's experience have been significantly altered. In an effort to free the information desk from increasing customer interruptions, the fireplace in the alcove space was boarded up and the area converted into a store for the Rocky Mountain Nature Association. [55] While this change might have solved that problem, it also significantly reduced available lobby space. Not only is the lobby typically overcrowded, but alterations to the auditorium and balcony have redefined the visitor circulation pattern. The installation of a new movie projector sealed access to the exterior balcony. The circuit around the balcony and through the auditorium was permanently closed, and access to the viewing platform was limited to the single door at the extreme southwest corner of the lobby. In 2000, visitors who actually find this entrance and walk around the balcony are forced to retrace their steps. Although a seemingly minor element in the overall plan, this circuit of park views was a crucial part of the building's program as originally designed. Without such free and easy circulation through the spaces, the sense of interior and exterior space is disturbed; the box is no longer broken. Perhaps most important, the dramatic view of Long's Peak ceases to become part of the visitor's experience.

Figure 65. According to the original circulation plan, visitors passed from the lobby to this outdoor mezzanine, circled the east end of the building, and entered the auditorium from the south facade. The square set into the concrete pillar was intended for a diorama, most likely with information about Long's Peak, which would have faced the visitor at this vantage point. (Photo by author, 1999.) |

Planning for the first repairs to the building began in August 1968, when modifications were designed to improve the faulty heating system. An alteration in the auditorium's central light fixture was also planned at this time. The working drawings for these improvements include details for constructing a new cupola on the auditorium roof as part of the heating and cooling system. Recent aesthetic and functional issues have been resolved through consultation with preservation experts. When light panels were in need of replacement in 1997, historical architects from the Intermountain Region suggested replacing the original lighting units with reproductions. Rather than install powerful T-10 hanging fluorescent lights, which would have significantly changed the office space, the park replaced original fixtures with panels that appear identical on the outside, but are textured on the inside to more effectively distribute light. [56] Unlike many Mission 66 buildings, the Headquarters has been maintained by a park staff that understands its historic and architectural value.

The Headquarters was listed in the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Utility Area Historic District in Rocky Mountain National Park's 1982 multiple resource nomination. In 2000, the park is in the midst of a rehabilitation project, which will provide an exterior comfort station and equip the area for handicapped visitors. These changes will involve a significant re-configuration of the parking lot, the creation of a plaza area, and new pathways between the restrooms and visitor center. The restrooms on the first floor will be replaced with park exhibits. In the design of this alteration, the Park Service has taken pains not only to maintain the integrity of the original building, but also assure that contemporary work conforms to the historic design.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

allaback/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 26-Apr-2016