|

National Park Service

MISSION 66 VISITOR CENTERS The History of a Building Type |

|

CHAPTER 6

Cecil Doty and the Mission 66

Visitor Center

The five visitor centers featured in this study are exceptional, both because they were designed by notable architectural firms and because they make up less than five percent of the facilities constructed for visitors during the Mission 66 program. From 1956 to 1966, the Park Service commissioned over one hundred new visitor centers and additions to existing museum buildings. Local contract architects were responsible for some of the designs, but the bulk of the work went to Park Service architects. Foremost among these in productivity was Cecil Doty, an architect from Oklahoma trained in the traditional Park Service Rustic style of design. [1] Along with a handful of his colleagues, Doty made the transition from the rustic—adobe or alpine depending on the natural and historical setting—to a modernist style stripped of such obvious associations with regional context. According to Doty, this shift from the old to the new architecture was entirely natural; he was simply doing his job under new parameters and within a changing social and political climate. While most of the selected contract architects were trained in an elite tradition of architecture as art, Doty was educated in architectural engineering at a manual arts school and spent almost his entire career working in the parks. When Doty designed modernist buildings, he did so within the Park Service tradition from which Mission 66 evolved. His buildings were not icons of modern architecture, nor were they typically among the buildings that are known for their Mission 66 character. Doty's designs were modest and utilitarian. As if in response to Director Wirth's greatest aspiration for his construction program—the creation of structures subordinate to the park landscape—Doty designed many unremarkable buildings. And yet, while much of the contract architects' work appears dated, Doty's buildings often achieve a kind of timelessness. Perhaps most important to the Park Service, his designs are sensitive to the site and historical context without being cheap rustic imitations or modernistic spectacles. The significance of the Mission 66 visitor center can only be evaluated after a closer look at the work of Cecil Doty.

In 1954 the Park Service reorganized the design and construction component of its four regional offices into two centralized facilities: the Eastern Office of Design and Construction (EODC) in Philadelphia overseen by Edward S. Zimmer and the Western Office (WODC) in San Francisco supervised by Sanford J. Hill. Although Director Wirth had yet to launch the Mission 66 program, this concentration of forces assumed the need for massive physical improvements and the organization necessary to execute a far-reaching construction program. The responsibilities of the respective offices included supervising the preparation of master plans and construction projects, conducting surveys and research, and preparing building plans and specifications. [2] These duties would not change with Mission 66, the planning of which began in earnest during the spring of 1956, but they would be magnified many times over. Such an influx of design work demanded that the Park Service hire contract architects from the private sector. This policy of hiring outsiders was not new. During both World Wars, the federal government called upon modern architects, many of whom were recent European immigrants, to help design wartime housing. The New Deal programs that had done so much for the parks during the 1930s and 1940s relied heavily on the expertise of private architects, designers, and craftsmen. As supervisor of the Civilian Conservation Corps state parks program, Conrad Wirth had firsthand experience with such successful partnerships. The CCC programs not only established the Park Service's reputation for well-built rustic style buildings, but also set a precedent for collaboration on such projects. A chief architect might sketch a design, and then pass it on to his staff to refine and embellish. For Wirth and many of his most trusted employees, the Mission 66 approach recalled the CCC effort. [3]

The new program's contract policies were outlined in a memorandum to the Park Service field offices in March 1956, explaining that superintendents were responsible for determining which projects would be completed by contractors and which by day labor. In general, it was "the policy of the Department and the Service to accomplish as much construction work by contract as is possible. It expedites the obligation of funds and assures completion of projects within the amounts available. Day labor is to be used only in exceptional cases where contracting is not practical." [4] Members of the design and construction offices had been forewarned of such changes in procedure. During their conference at Great Smoky Mountains (April 1955), they had discussed the Mission 66 program and immediately issued several statements and recommendations based on general consensus. The Park Service design offices voiced their "wholehearted support" for the program, which would obviously expand their role in park architecture and planning. In anticipation of Mission 66, they suggested that Wirth prepare a construction schedule by region to guide them in gathering data and developing surveys necessary for such extensive design work. The offices of design and construction also deemed themselves best equipped to create plans and specifications for construction projects and to prepare the preliminary drawings for all buildings. Professional private offices could then produce construction drawings on a contract by contract basis. It was recommended that the two regional offices be granted "contract authority to negotiate with professional firms in private practice, of recognized ability." [5] According to this arrangement, Park Service architects were entirely responsible for design concepts, while contractors merely performed the routine work of drafting working drawings. In practice, the relationship with contract architects would vary according to project, but it would usually involve some collaboration with Park Service colleagues.

That construction projects were underway by mid-summer is indicated by a communication from Director Wirth admonishing superintendents and regional directors for expanding their projects beyond the established limits. Evidently, some supervisors were using up emergency funds in the first contract, leaving little margin for over-runs or contingencies. Even more potentially devastating was the fact that unauthorized adjustments in contracts were affecting the planning schedule, which was established two years in advance. A single misjudgment could start "a chain reaction," and necessitate the revision of the entire schedule. [6] Field offices were to required to submit change orders and other cost overruns to the regional director for approval.

Cecil Doty and the NPS

Tradition

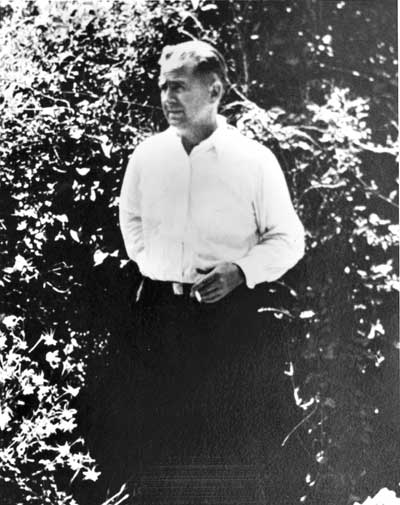

One of the most prolific designers in Park Service history, Cecil John Doty (1907-1990), is also one of the least known. Doty's absence in the annals of Service history reflects both the nature of architectural collaboration and the fact that he never entered the supervisory ranks of the Park Service. His name is often scrawled on the title block in the corner of a drawing, but has no place in administrative histories. And yet, in his thirty-five-year career, Doty worked with some of the Park Service's most famous designers and created many of the buildings park employees use every day. Doty grew up on a farm in May, Oklahoma, and graduated from Oklahoma A & M (now Oklahoma State) with a degree in architectural engineering in 1928. During his college years, Doty remembers the influence of "Paul Cret by proxy." The famous Philadelphia architect was a mentor to one of Doty's instructors who had recently graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. Through Cret's work, Doty was introduced to Beaux-Arts neoclassicism adapted to modern tastes. [7] Doty credits his sense of "progressive architecture" to this early exposure to Cret's design.

Figure 66. Cecil John Doty. (Courtesy National Park Service Region Three Headquarters, Santa Fe.) |

During the Depression, Doty was lucky to receive occasional work from the local architectural firm Valberg and Drury. He also briefly taught freehand drawing and architectural history at his alma mater. The 1930s was a difficult time to open private practice, and Doty's effort to launch a firm in Oklahoma City failed. Soon after, he joined the CCC state parks program, working under the title "file clerk" in the newly established office before officially signing on as an architect. Director Herbert Maier hired Doty to finish plans for a museum at Glacier. As Doty later related, his early architectural experience mirrored that typical of young draftsmen: he worked under the principal designers, imitating their style as much as possible. Doty and his fellow draftsmen were encouraged to look through photographs of Maier's work, which they called "The Library of Original Sources." Many of these photographs appear in three paperbound manuals compiled in 1935 to guide CCC employees in architectural design. [8] Although Doty expressed pride in one of his favorite projects from this period, the museum in Custer State Park that he drew up on the dining room table of a log cabin, he also admitted that it was "a pretty cold copy off" Maier's Norris Basin Museum. [9] In January 1935, Doty was given the position of associate engineer and paired up with landscape architect Harvey Cornell for state park work in Oklahoma and Kansas. [10]

When the Oklahoma office was reorganized in 1936, Doty became regional architect, and, the next year, followed Maier to the new regional office in Santa Fe. A contingent of young architects from Oklahoma A & M—Raymond Lovelady, Milton Swatek and Lada Kucera—also moved to Santa Fe. [11] The reorganization marked Doty's shift from work in state parks to national parks, which took place when the programs were officially combined. In the months preceding the move, Doty recalls preparing the initial design for his future office, the Santa Fe Region Three Headquarters. He created preliminary plans having never seen the site, with inspiration from memories of the area and, perhaps, the Library of Original Sources. [12] After visiting the site in July 1937, Doty prepared the final sections and elevations. It was a traditional adobe building, one-story except for a double-height entrance area, with exposed timber vigas and adobe bricks constructed on site by the CCC. [13] Newspaper accounts of the building praised Associate Architect Doty for a fine adaptation of regional architecture. The cover of the first "National Park Service Region Three Quarterly," of which Doty was art editor, featured the architect's pen and ink drawing of the new building.

Figure 67. Region Three Headquarters, Santa Fe. (Courtesy National Park Service Region Three Headquarters, Santa Fe.) |

In 1939, Park Service Architect Albert H. Good, compiler of Parks and Recreation Structures, expressed admiration for the headquarters and imagined an expanded role for its style in the future. "If the so-called modern, or International Style, of architecture is to gain in popular appeal so that it is universally adopted . . .there is probably in the United States no traditional architecture so kindred and complementary to it as the early architecture of the southwest. Broad, simple surface, a sense of the horizontal, and setbacks are common to both." [14] Although Good considered the presence of modernism in historic areas "unfortunate," he also realized that the style could be employed without transforming the scale and atmosphere of cities like Santa Fe. Good's statements not only demonstrate that the Park Service understood the potential of modern architecture nearly twenty years before Mission 66, but also that the boundaries between the two styles were not so rigid. Unknowingly, Good predicted the ease with which Doty would move from the horizontal planes of southwestern rustic to the flat roofs and low silhouettes of modern visitor centers.

After designing his first National Park building, Doty worked on various smaller projects before transferring to the San Francisco Region Four Office in 1940. It was probably here that he assisted Lyle Bennett, the designer of the southwestern style buildings at Bandelier, on plans for several similar structures at White Sands National Monument in New Mexico. [15] During the war he worked briefly for the Navy, and on other federal projects such as the Alcan Highway, Lake Texhoma, and Shasta Dam. Doty returned to the Region Four office in 1946 and two years later became regional architect. His post-war designs include the lodge at Hurricane Ridge in Washington's Olympic National Park (called the Public Service Building in the early 1950s) and the administration building at Joshua Tree National Park in Twentynine Palms, California. [16] The Olympic project featured designs for exotic wood carvings adorning the entrance to the lodge and an entire lobby full of furniture. Its fancy woodwork aside, the building was built of reinforced concrete walls with wood paneling and sheet metal flat and shed roofs. Indian designs were stenciled above the south elevation of large plate glass windows. Aspects of the Mission 66 visitor center Doty would design for Hurricane Ridge in 1964 are not so different from the aesthetic employed at the lodge. These designs indicate that Doty and his Park Service colleagues were already moving in a progressive direction; although the specific attributes of the visitor center had yet to be developed, the prevailing influence was definitely modern. In the early 1950s, Doty was promoted from Region Four architect to designer; in 1954 he followed Sanford Hill to the Western Office of Design and Construction in San Francisco. [17]

Just before the Park Service's next major reorganization, Doty designed a complex of public service buildings for Everglades National Park called Flamingo Marina. [18] Although the design included a Park Service administration building, it also featured a lodge, restaurant, gas station, and an elaborate dock into Florida Bay with facilities for cruise boats. Buildings were modern—concrete block, flat roofs, swirling concrete ramps, and terraces supported by thin columns. Patterns of louvered windows and perforated concrete screens provided ornamentation. Flamingo Marina is a resort of the type that became ubiquitous on the nation's beachfront in the 1950s and 1960s. Although Doty mentioned "a major change," reducing the size of the Park Service building at Flamingo and some alterations to the restaurant, the compound was built basically as designed. The marina project suggests that the Park Service began equipping parks with facilities to accommodate increasing numbers of visitors in the early fifties. As a development program, Mission 66 hoped to supply facilities to encourage public use, even if this meant boating in the Everglades and skiing in the Rockies.

Figure 68. Flamingo Visitor Center and Restaurant, Everglades National Park, 1958. (Photo by Jack E. Boucher.) |

Doty's first major design for WODC, the public use building at Grand Canyon, has already been discussed as a prototype for the visitor center. According to museum specialist Ralph Lewis, Tom Vint and Cecil Doty visited the Grand Canyon in July 1954, and Doty "began to design preliminary floor plans on the spot." [19] His design is most interesting, in retrospect, as an illustration of the transition from a simple program to one with more sophisticated requirements. The Grand Canyon building borrows the Santa Fe office floor plan, but incorporates modern facilities, such as an auditorium, into a more free-flowing version of the traditional courtyard layout. Despite its unified plan, the public use building looks more like a factory than the southwestern building style it tried to modernize. The two-story office space does not modulate the facade, as in Santa Fe, but rather adds an industrial feeling to the white-walled building. Efforts to moderate the harshness also mark this as a transitional building—exterior stone walls and flagstone are brought inside the lobby space; the exterior features large masonry columns; the courtyard is lined with a covered walkway supported by columns tapered on the side and includes native plantings. Although Doty obviously made an effort to temper the modernist style, his concessions seem tacked on. The building would appear more comfortable stripped of its rustic trappings. The public use building at Grand Canyon was clearly an experimental building, and, along with the similar facility at Carlsbad Caverns, defined the emerging model visitor center. [20] Both buildings were retrospectively renamed visitor centers. With the guidance of Vint and Lyle Bennett, Doty was instrumental in developing a modern visitor center design that would fulfill the programmatic demands of Mission 66.

Figure 69. The interior courtyard of Grand Canyon Visitor Center, 1998. (Courtesy National Park Service.) |

Despite the shocking transformation in architectural style exhibited at the Grand Canyon, Doty understood that Mission 66 architecture evolved within the Park Service tradition: "Most of what we see . . . was the work or direction of Tom Vint and Herb Maier. To me Vint, Wirth, Maier, (Hillory) Tolsen, (Dick) Sutton, (Sanford 'Red') Hill was the Park Service." Like Maier, Vint had made his career supervising the design of some of the landmarks of rustic architecture; the office he headed in the 1920s developed the Park Service Rustic style. But after the War, rustic no longer satisfied park requirements, either in terms of function or aesthetics. As Doty explained, he and his colleagues had witnessed some of the nation's great technological and engineering achievements—the Empire State Building, Radio City, and the Chicago World's Fair, not to mention the advent of television, the motion picture, and the origins of space travel. When questioned about this in an interview, Doty responded with his own question: "How could you help but go away from that board-and-batten stuff?" [21]

Characteristics of a Doty

Design

Although Doty's drawings of visitor centers exhibit a distinctive rendering style, it is impossible to distinguish between his contributions to the Mission 66 building type and those developed by the Mission 66 design staff. Nevertheless, Doty's buildings share certain attributes: a sensitivity toward location; a compact plan incorporating standard visitor center elements; the use of modern materials combined with wood and stone; and the impression of modesty that comes from a limited budget. Although locations may have been chosen by Park Service planners, Doty attempted to establish a relationship between the building and the landscape. In some cases he emphasized circulation through the building to an exterior view; other structures were designed around glassed-in observation decks. Every Doty plan incorporated basic visitor center elements, including exhibit areas, audio-visual rooms, auditoriums, restrooms, and lobbies. Doty juxtaposed these spaces and combined two or more in small visitor centers to accommodate limited programs. Financial circumstances dictated aspects of the program throughout the design process, restricting square footage, choice of exterior and interior surfaces, and the extent of exhibit facilities, among other features. In most of his designs, Doty masked the inexpensive nature of his buildings with aesthetic choices, such as the use of finer materials around the entrance area.

If practical considerations often favored the utilitarian, Doty was certainly aware of the status bestowed upon the visitor center, both by the Park Service and by tourists who were directed to the facility upon entering the park. Recalling Vint's assessment of the visitor center as "the city hall of the park," Doty expressed his belief in the architectural importance of these public buildings. Visitor centers represented the Park Service's highest ideals, and they provided essential services. Doty hoped that his visitor centers would also exude a sense of pride in their surroundings—inspiring the Park Service to maintain the buildings and the public to refrain from littering or other destructive behavior. Even as he strove for the equivalent of civic monuments within the park surroundings, however, Doty realized that funding limitations would always curtail the Park Service's aspirations, sometimes even before projects reached the drawing board. The need to conserve and compromise was integral to Mission 66 design and would prove to be Doty's greatest challenge. Nevertheless, Doty's commitment to architectural excellence extended to every facility—whether visitor center or utility building. Even functional structures hidden from view were judged by aesthetic standards: "do you like it, does it please?" [22] The following sections discuss how Doty used architectural aesthetics to fulfill Mission 66 requirements in his visitor center designs.

Circulation and Organization

Doty considered the visitor center that he designed for Zion National Park, Utah, in 1957 one of his best, perhaps because it combined several of his most effective methods for organizing spaces and providing efficient circulation between them. Many of the features used so well at Zion were prominent in his later buildings: the central skylight, the two-story office wing, and the rear viewing terrace. The fact that, many years later, an expanded bookstore area would compromise the lobby space is also, unfortunately, characteristic of many of these buildings. The Zion facility is divided into a visitor center area and a two-story administrative wing that can be entered from the rear, an arrangement similar to that of the Headquarters at Rocky Mountain and Colorado National Monument's visitor center. This design strategy successfully segregates visitor traffic from administrative areas, while aesthetically highlighting the building's public service function. Visitors rarely notice the office wing, as their attention is directed from the parking lot to the exterior restrooms and lobby entrance. The administrative aspect of the building is not part of the visitor experience.

The Zion Visitor Center combines the idea of walking through the building to a viewing area with the central "hogan" skylight, both of which were also used a few years later at Wupatki National Monument near Flagstaff, Arizona. Whenever possible, Doty framed views to help determine visitor circulation and give additional functional meaning to a building. At Organ Pipe Cactus in Arizona, Doty encapsulates the view of the park with glass front and rear facades. Colorado National Monument encourages the visitor to walk through the building for a dramatic glimpse of the canyon. Even the stark Canyon de Chelly Visitor Center in Arizona, located away from the monument's featured canyon, includes a viewing terrace; the surrounding landscape did not have to be the most dramatic of the area to require an outdoor porch. This arrangement was also used for the Madison Junction Visitor Center at Yellowstone, where visitors entered the porch and then passed from the lobby to a wood deck called the "view lobby." To the left of the entrance space was an exhibit area and to the right, an auditorium. The visitor center at Mount Rushmore (now demolished) was one of the few examples featuring a path bypassing the lobby. Visitors could proceed directly to the view terrace and enter the building from the exhibit room.

Figure 70. Zion Visitor Center in 1998. (Courtesy National Park Service.) |

Although Doty often creates pathways through his buildings, he also assumes that the visitor's first stop is the lobby—the location of the information desk, maps, and other orientation material. Additional services, such as the auditorium and exhibits, are more or less subservient to this central space. Sometimes, Doty treats these areas as entirely separate rooms, but, more frequently, he uses a free-flowing plan to blur the boundaries between the various service areas. The exhibit space at Montezuma Castle in Arizona blends into the lobby; at Canyon de Chelly, only a half-room partition separates the video presentation area from the museum. Upon entering the lobby of Colorado National Monument, one naturally turns right to examine the exhibits. The Hoh Visitor Center in Olympic National Park treats lobby and exhibits as a single entity. Because of its larger size, Zion houses its museum and auditorium in completely enclosed rooms separated from the information desk. A similar arrangement is used at the Death Valley Visitor Center, where the auditorium and exhibit space flank either end of the lobby. This building is loosely arranged around a courtyard, the visitor half of which is owned by the state of California. Although located just across the courtyard, the administrative wing is Park Service property.

As if to prove that his plans depended on many factors, Doty designed two visitor centers with unusual programs in the final years of Mission 66. The visitor center at Sunset Crater, Arizona, located some distance from the crater itself, is the simplest possible in terms of circulation and use. It is essentially one big room with offices on one end and restrooms on the other. No effort is made to obtain a view or direct the visitor outside. Just a month later, Doty designed a complex of three "huts" for Center Point in Curecanti, Colorado. Although this visitor center appears to function as three distinct buildings, interior areas are linked. One corner of the lobby leads into the exhibit space, the second of the three square huts. Restrooms are attached to this area but entered from the outside. The final hut is an office wing entered from behind the information desk in the lobby. This portion of the visitor center is partitioned into several offices and work spaces.

Figure 71. Visitor Center, Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument, near Flagstaff, Arizona. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

As much as one would like to isolate various types of Doty visitor center plans based on location and regional requirements, there is no standard pattern. Emphasizing the relationship between inside and outside—bringing the outdoors in—was a characteristic of Doty design, but it was also common to modern architecture in general. Like the flow diagrams drawn up during design conferences, Doty's plans shuffle components according to many factors, not the least of which was budgetary. The architect himself was quick to acknowledge that design ideas often entered his head for no reason at all. Behind all of Doty's work, of course, was not only an architectural background, but a lifetime influenced by extreme social and technological change.

In a presentation at the WODC conference on visitor center planning of February 1958, Doty articulated his ideas about visitor center design using "space relationship diagrams" of Badlands National Park and Theodore Roosevelt National Park, two sites of current interest. As Doty explained, traffic flow diagrams were most useful in the early stages of planning, when the architect was engaged in the initial three steps: considering traffic through the entire park, analyzing flow in the visitor center zone, and planning for the parking area and visitor center itself. Circulation through the building should be clear without posted signs. "If the circulation is simple and obvious, and space is adequate, then clockwise, or counter-clockwise flow, locations of information counters, etc., become somewhat incidental." [23] Doty's diagram's illustrated his belief in free-flowing movement through buildings with arrows indicating entrances and shaded areas showing circulation in any direction. The "lobby," "exhibits," and "audio" were analyzed according to the percentage of space devoted to various activities, including viewing, standing, displaying information, and circulation. Although Doty's conference presentation suggests a calculated approach to design, this methodology was probably not intended as an architectural model, but merely as a guideline for more flexible planning.

Style and Materials

Both in terms of theory and practice, modern architecture involved new materials and new uses for old materials. Steel and concrete were not modern materials per se, but, when deliberately exposed and exploited, they became part of the modernist aesthetic. Steel frames and concrete shells allowed lobbies to become open areas unobscured by load-bearing walls. The most significant adaptation made by Park Service architects, after compensating for view terraces and observation areas, was in the treatment of materials. Doty and his colleagues always mingled traditional materials, like stone and wood, with steel, concrete, and glass. This mixture of old and new followed the Park Service's tradition of "harmonizing" with the landscape, sometimes in a deliberate attempt to establish continuity between existing rustic structures and modern additions. If this conservative combination of materials did not stretch the boundaries of the modern style, it did result in some distinctive park buildings.

The Zion Visitor Center featured both canyon-colored brick and masonry and tapered steel columns encircling entire walls of glass. At Sunset Crater, sawn shakes and a water table of volcanic rock clashed with the glue lam framing, crinkled roof, and tapered columns. The visitor center at Tonto National Monument in Arizona, for which Doty prepared both preliminary and working drawings, incorporated laminated beams and glass paneled walls in an upper deck. One end of the east elevation was stone veneer over concrete, the other stucco on concrete blocks. Death Valley featured porcelain metal louvers on the east elevation, the same Lemlar brand used in the office wing at Gettysburg, and Organ Pipe Cactus included concrete block screens similar to those popularized by Edward Durell Stone. Lassen Volcanic was rustic in outline, with its pitched roof suitable for alpine climates, but the roof was metal and supported by laminated beams. The Navajo Visitor Center in Arizona was a flat-roofed rectangular building with a front facade of native stone and glass and a sign of "rough-sawn" lettering. Park Service architects did not simply build modern structures; they incorporated many of the most blatant features of modernism, including the tapered column, aluminum-framed window wall, and concrete block screen. In most cases, they felt obliged to temper such choices with traditional building materials.

Although many Mission 66 visitor centers provide clues to their origins, usually in exterior masonry patterns, window frames, and roofs, the visitor center at Canyon de Chelly might have been built yesterday. The functional brick structure offers no obvious indication of a date. On the inside, however, period museum exhibits suggest its Mission 66 vintage. In this case, limited means resulted in a building that not only appears timeless, but has actually become more appropriate for the surrounding landscape over the years. The road to the building takes the visitor through the Navajo Nation Indian Reservation. Buildings on the reservation range from public housing projects, modular and mobile homes, to homemade cabins and traditional hogans. The utilitarian visitor center is more appropriate here than anything alluding to ancient civilizations, especially since Native Americans still farm land on the valley floor.

If the Canyon de Chelly Visitor Center did not boast dramatic modernist columns or glass walls, its very simplicity demonstrated Doty's increasing comfort with the modern style as the Mission 66 program entered its final years. In preliminary (unbuilt) projects for Cabrillo National Monument (1963-1964) in San Diego, and Cedar Breaks National Monument (1965) in Utah, Doty designed modernist facilities with expansive glass-walled viewing decks overlooking the sites. The buildings resemble ocean liners, at least in elevation. The only ornamentation was provided by clay grilles at Cabrillo and the pattern of concrete block and aluminum sun baffles on the facade of Cedar Breaks. An observation deck at Cabrillo featured a band of windows surrounded by concrete, like a control tower, while the Cedar Breaks observation area was floor-to-ceiling windows that alternated between sash and pivot. Although neither building demonstrates major changes in terms of plan or circulation, these later visitor centers show a significant adjustment of aesthetics. The modernist style is no longer covered with a "rustic" veneer or tempered by natural wood details. At Cabrillo, the "mission tile color" of the grilles appears to be one of the few concessions, while Cedar Breaks includes a "large rock" adjacent the square metal columns marking the entrance.

Doty used the compact, minimalist aesthetic for some of his later designs, but others boasted dramatic cylindrical forms fashioned of poured and cast concrete. Among such projects were proposals for visitor centers at Glen Canyon Dam, Mesa Verde, and Natural Bridges, all of which incorporated cylindrical elements into their plans. The Glen Canyon building, designed in 1963-1964, consisted of a rectangular wing with offices and visitor services attached to a cylindrical "observation and display" space and exhibit area. In elevation, the cylindrical observation room was emphasized by an overhanging flat roof, like a plate, with a central skylight housed in a much smaller cylinder. The visitor spaces at Natural Bridges (1964) were arranged within an oval. Concrete arches over the cylindrical area add to the feeling of free-flowing space. Masonry veneer, a split-block wall section, and wood trim were included in the decor, but the dramatic concrete shell was hardly influenced by such details. Just a few months later, in August, Doty employed the cylindrical form in an exhibit space placed within a roughly triangular lobby and audio-visual area. Offices and concessions were contained within a rectangular wing perpendicular to the lobby. The cylindrical form of the exhibit hall was mirrored in the round shape of the front terrace. The use of cylindrical forms has no apparent relationship to the site conditions; in fact, previous designs might have used the shape to greater advantage for panoramic views in many locations. It's likely that Doty had become increasingly interested in stretching the possibilities of steel and concrete construction. By 1964 Park Service Modern had become a style, and Doty was free to take more risks in its execution.

Three Southwestern Visitor

Centers

During the Mission 66 program Doty designed visitor centers for a range of climates and locations, according to varying needs and anticipated visitation. In some cases, he never visited the site, and in others, he executed final working drawings. Rather than compare such a divergent group of designs, this section will look more closely at three small visitor centers in Arizona, all serving as the gateway to ancient ruins. In the design of these modest buildings for relatively obscure parks, Doty shows his versatility in adapting to site conditions. At Montezuma Castle and Wupatki Ruins, the buildings are located on pathways to the ancient structures. Doty had no choice but to build at the edge of Walnut Canyon, where an existing building provided the foundation for his modern addition. The three visitor centers illustrate the extent to which terrain and natural surroundings influence the perception of modern park buildings. Modern architecture is most successful in places where the site obscures and overwhelms—such as Montezuma Castle—and when it clearly uses modern technology to advantage by providing more dramatic viewing opportunities—such as Walnut Canyon.

Figure 72. Entrance to Montezuma Castle Visitor Center, 1969. (Courtesy Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

The visitor center at Montezuma Castle, designed by Doty in 1958, is so shaded by native trees and the adjacent hillside that architectural style is hardly an issue. In this design, Doty had the foresight not to place the building in an open clearing, but to wedge it into the canyon, longwise. The visitor follows the path from parking lot to restrooms, and then continues to the lobby entrance. The information desk is to the right of the door, but open to the entire space, which includes a sales area and exhibits. Park offices are entered from behind the desk. The dark, enclosed space seems appropriate in this narrow site, and actually pushes the visitor towards the far end of the lobby, where a door leads out to the ruins. A concrete path winds the half mile to the ruins and continues in a short loop around the canyon. The visitor center includes an adjacent terrace with serpentine curb that overlooks a shaded picnic area. The terrace was paved around trees, which now appear to grow from the concrete. On paper, the flat-roofed metal-and-glass building appears a quintessential modernist facility, but in fact, the building is a remarkable example of how modern architecture can actually fade into the background. Little needs to be said about Walnut Canyon—a visitor center almost impossible to photograph—because it so deliberately and successfully attracts little notice.

Figure 73. Montezuma Castle Visitor Center, rear entrance and path to ruins, 1969. (Courtesy Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

At Wupatki Ruins, Doty confronted a more open, high desert landscape that he had studied before. Wupatki is one of several sites in northern Arizona featuring significant ruins of ancient Indian communities. Although most of these ruins are cliff dwellings, such as those hunkering down in the valley at Canyon de Chelly, Montezuma Castle, and nearby Walnut Canyon, the remains at Wupatki rise from a relatively flat area; the ancient settlement's free-standing walls stand exposed upon the rocky high desert. In the early 1940s, Doty had designed a small administration building at the monument. His solution to the siting problem involved constructing the building up against a nearby rock formation. This early design was considered an extension of an existing residential building, even though a patio separated the structures. The new visitor center was to be an enlargement of this early administrative facility. In his original design, Doty had cultivated the familiar southwestern theme, creating a rough masonry building with carved wooden corbels under the eaves, exposed vigas, and canales. His Mission 66 addition effectively obliterated the older building, as it shifted to an abstract version of Native American architecture, imitating both the nearby stonework and the traditional methods of residential construction. The "hogan" shape of the lobby with its central skylight was a reoccurring spatial motif in Doty's visitor centers. Along with its relatives the kiva and teepee, this glass-covered cone was considered appropriate for many situations involving Indian heritage in western and southwestern states.

In May 1957, several years before Doty arrived on the scene, Wupatki mounted a promotional Mission 66 display. The introductory panel explained that, "in this exhibit Wupatki will be used as an example of what needs to be done in Arizona and throughout the United States Parks and Monuments." [24] Successive panels commented on the importance of Mission 66 as a method of preservation. [25] Finally, in November 1961, Doty visited the site in preparation for the long anticipated visitor center, scheduled for construction in 1963. [26] Six months later, Superintendent Russell L. Mahan praised "Architect Doty, WODC" for submitting an excellent floor plan. Mahan approved the preliminary plans with only minor suggestions and looked forward to the start of the spring construction season. [27] In December, Park Service representatives from the WODC and architects Leslie J. Mahoney and R. Gilman visited Wupatki to discuss the site and potential building materials. The firm of Lescher and Mahoney, Phoenix, which received the contract for final drawings, had already completed similar work for the Park Service at Organ Pipe Cactus, Arizona, (1956-1958) and was involved in the additions and alterations at Casa Grande (1962-1963).

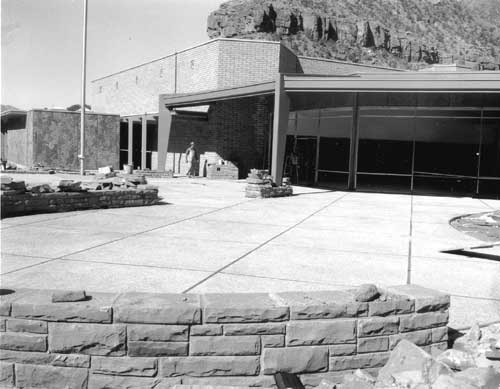

Bids for the construction of the visitor center were first opened in July 1963, but higher than anticipated costs forced the park to delay the bidding process until September. [28] Work began on July 6, and, by end of month, footings had been poured and forming begun on foundations. [29]

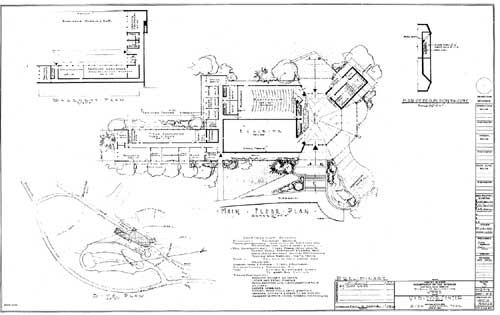

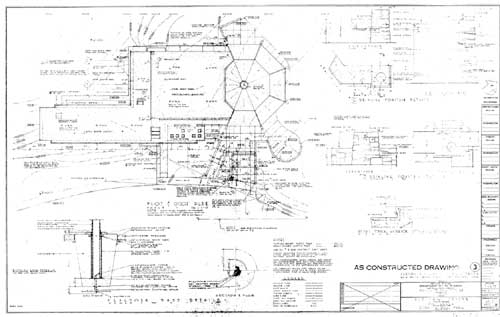

The design of the visitor center at Wupatki Ruins is an excellent example of how the Park Service typically handled small Mission 66 projects at the height of the improvement program. Doty sketched two sheets of preliminary plans and the contract architects filled in the details. Whereas Doty simply labeled the central space "lobby" and "exhibits," separated by "skylites," Lescher and Mahoney indicated precise measurements, wall panels, construction details, and the 4,905-foot elevation. Although Doty's sketches give a better sense of the final building, the architects' plans provide the contractors with the information to actually build it. Like most of the visitor centers protecting ancient ruins, the Wupatki building blocks the view of the featured attraction. A flagstone path leads to the front entrance and the restrooms, entered from a sheltered walkway to the left of the building. Immediately upon entering, the visitor confronts an information counter on the right, adjacent the office wing. The octagonal lobby is illuminated by a central skylight divided by a partition separating exhibits from the sales area. Doors at the far end of the room lead to a flagstone patio and path to the ruins. The information counter stands guard next to the office wing, equipped with space for rangers, clerical work, and the superintendent's office. The park's historical archives are stored in part of the old building at the end of the path leading to the restrooms.

Figure 74. Visitor Center, Wupatki Ruins, near Flagstaff, Arizona. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

From Doty's drawings, one imagines an even more modernistic building than that actually built. The exterior appears covered by a wall of vertical louvers, the office windows are severe; in plan, the central serving area and office appendages suggest a complicated building program. Actually, the Wupatki Visitor Center is small, simple, and understated. It fits in nicely with the nearby residential buildings and surrounding landscape, in part because one side of the building is pushed up against the rock hillside and existing administration building. Inside the lobby, the architect specified paneling of warm, western pine and a cedar information desk. Wupatki illustrates the positive and negative aspects of the Mission 66 plan. In achieving the goal of a simple architectural style with little impact on the landscape, Mission 66 designers created buildings almost too plain to criticize. They fulfill their function within budget, but hardly inspire. And yet, Doty's plan manages to use the original building—essentially a basement in the hillside—without inheriting the gloom and dank of this space. The Mission 66 goal was to solve the problems of visitor service and circulation, after all, and these requirements are certainly satisfied.

The Mission 66 visitor center at Walnut Canyon was also an addition to a building designed in the CCC era. During the planning phase, Doty and Vint visited the old building on the edge of a valley overlooking an intricate series of cliff dwellings. Doty remembered enthusiastically "talking about how you could do this and you could do that [with a new building]." Vint reminded him of the visitor center's practical function, which was not intended to showcase an architect's skill. [30] With this advice in mind, Doty went on to transform the older building with a glassed-in observation deck. The visitor center at Walnut Canyon took advantage of its site by bringing the visitor from the entrance down stairs to the lower viewing level, a series of terraces that imitated the natural surroundings. From here, the visitor confronted the spectacular canyon, as well as outdoor viewing opportunities.

Figure 75. Visitor Center, Walnut Canyon National Monument, near Flagstaff, Arizona. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

More than the Wupatki addition, the extension of the administration building at Walnut Canyon allowed for an advantageous use of modern architecture in the expansive lobby viewing area. In cases such as these, the modernist style extended the boundaries of a space, actually opening up a window on the site. However, when such opportunities didn't present themselves, it was difficult to create a visually interesting building. Rustic architecture had the advantage of incorporating a certain amount of fantasy into its walls and appealing to stereotypes of the wild, rugged West. The rejection of this style also represented the beginning of a more serious attitude towards preservation and interpretation. Park Service Rustic was the architectural equivalent of "living history," a method of visitor entertainment the Park Service hoped to substitute with informative literature and educational programs. The very roots of modernism were founded in standardization, the attempt to create mass-produced housing for example, and, as a style, its use mirrored the Park Service's massive effort to provide adequate visitor services at every national park.

Figure 76. View of lobby from observation area, looking towards entrance, Walnut Canyon National Monument. (Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.) |

Zion Visitor Center

A cottage cannot be transformed into a skyscraper merely by adding story upon story. Zion cannot be equipped to serve doubled and redoubled numbers of visitors merely by expanding existing facilities in their present location. [31]

Planning for a new visitor center at Zion National Park began a decade before the Mission 66 program. During the 1940s, the park accepted proposals for a new museum to replace the existing one-room facility. Since its establishment in 1919, the park had more than doubled its visitor population every ten years. The museum at the juncture of the main highway and the Zion Canyon spur road was a desirable stop for visitors entering the narrow canyon area, but overcrowding and traffic jams had become such a problem that many were denied the opportunity. In its 1951 master plan, the park suggested a combined museum and administration building that would concentrate both the public and the staff offices in a single location. Such an expensive project hardly seemed possible at the time. But park planners became more optimistic during the summer of 1956, when President Eisenhower signed a bill expanding the park. The Kolob (western) section was then opened to the public and funds were provided to purchase several inholdings. Work began on the West Rim Trail in 1957. [32]

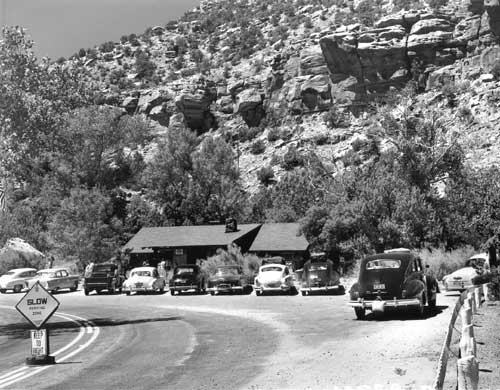

Figure 77. The Zion Museum, n.d. (Courtesy Zion National Park Archives.) |

When Mission 66 funding and planning came to Zion National Park, discussion focused not on whether a new building was necessary but on where it should be located. The park's Mission 66 prospectus described a facility outside the crowded canyon. Along with the construction of this visitor center at the south entrance of Zion Canyon, the park proposed a new road into the Kolob canyons. The new access was to be designed with pull-outs and interpretation to encourage visitors to explore, picnic, and linger in the area. Cecil Doty began preliminary studies for the visitor center in October 1956, before a site location had been finalized. [33] The next spring, the park sent studies and recommendations to the WODC and Region Three office. Robert Hall of the WODC and Merel Sager of the Washington office met with Superintendent Paul Franke in May 1957 to discuss "an alternate site for the visitor center" suggested by Director Wirth. According to one oral history interview, the controversy over the location of the building lasted for over a year because Wirth favored locating the structure adjacent to the old museum. Superintendent Franke insisted that the canyon location was too crowded, both with visitors and geological formations. Mission 66 planning influenced the choice of a site outside of the main canyon, a site with its own natural beauty but one that would not detract from the park's featured scenic attractions. [34]

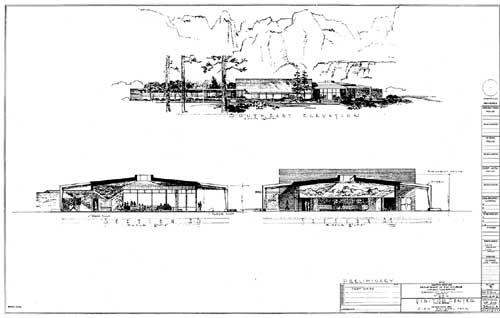

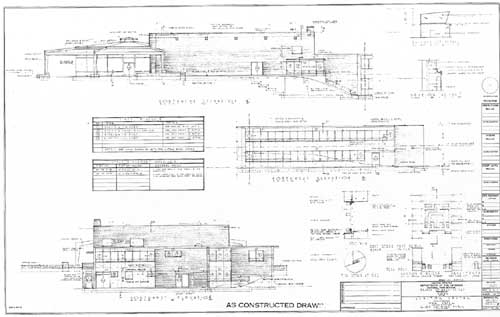

Any arguments surrounding the siting of the visitor center were resolved by November 1957, the date that Doty completed two sheets of preliminary drawings for a building off the south entrance road with a view of the canyon to the north and the Towers of the Virgin to the east. In elevation, the visitor center appears as three discreet sections: the steel and glass lobby area, the rectangular museum and auditorium, and the low office wing. The path from the parking lot leads to steps and a broad front terrace from which visitors enter the hexagon shaped lobby oriented toward scenic views. In contrast to the more conservative decor of the office wing, the lobby features modern details. Tapered, spider-leg columns support the overhanging roof; the lobby is almost translucent, its glass walls extending from floor to ceiling. Inside, a central skylight further dramatizes the effects of light and spaciousness. An information desk stands to the left of the skylight between the entrances to the exhibit space and auditorium. The restrooms are located on the north side of the lobby. Although this placement of the restrooms blocks one segment of glass wall facing the canyon, it also directs traffic to the far end of the lobby. Black arrows on the original drawings indicate that Doty intended visitors to pass through the lobby to a framed view of Towers of the Virgin, the rock formation behind the building. Visitors were encouraged to walk out to the exterior viewing terrace, which wrapped around the lobby in a geometric shape that mirrored the facets of its walls.

In elevation, the exhibit and auditorium portion of the visitor center is a transition between the modern lobby and the more conservative office wing. The double-height auditorium section is concrete block, its facade only adorned by alternating light and dark panels. By using a pattern of panels similar to those of the office wing windows, Doty developed a more uniform façade, though he seemed intent on maintaining its austerity. The contract architects, perhaps in consultation with their client, would soften his crisp lines with ornamental details. Despite the steel, glass, and smooth surfaces, however, Doty specified the use of redwood dividers in the exterior terrace, which was to contain natural stone walls and surfaces of exposed aggregate.

Although visitors parking in the main lot are certainly aware of the office wing, the low, utilitarian appendage to the visitor center attracts little attention. Employees park in the rear of the building and enter from the parking lot. A naturalist's study collection, restroom, and storage rooms are housed in the basement. The main floor includes offices for the rangers, superintendent, and other administrators; a conference room; and storage for administrative records. The office wing extends from the visitor center exhibit space and along the back of the auditorium, forming an "L" shape. A short hall from the front entrance leads to hallways in both parts of the L and hidden access to the visitor center via the auditorium. The facade of the office wing is only decorated by a strip of utilitarian windows, the simplicity of which contrasts with the imposing double-height auditorium and dramatic glass and steel lobby. In his drawings, Doty masked the facade of the office wing with a series of trees and shrubs. The office wing appeared subservient to the visitor center in every way.

During the next year, Doty's design for the Zion Visitor Center was handed over to the architectural firm Cannon and Mullen of Salt Lake City. [35] Howell Q. Cannon and James M. Mullen worked as partners beginning in 1949 but both had experience as employees of the firm since the 1920s. Cannon (1908- ), born in Salt Lake City, was educated at the University of Utah and received a bachelor's of fine arts from George Washington University in 1938. After working as a draftsman for Cannon & Fetzer for four years, he took a two-year European tour and then accepted a position as clerk and inspector of construction for the Architect of the Capitol in Washington, D.C. Beginning in 1938, Cannon supervised construction for Cannon and Mullen, overseeing work at the $400,000 U.S. Bureau of Mines Experiment Station in Salt Lake City. He was a member of the American Institute of Architects. The "specialties" listed in Cannon's resume describe him as an ideal candidate for Mission 66 contracts, with experience in "supervision of construction, architectural engineering work involving design of wood and steel and reinforced concrete stress members, specification writing, business contacts." James M. Mullen (1912- ), also a native of Salt Lake, spent two years at the University of Utah and was licensed to practice in the state. He was employed by several local firms to design a wide range of buildings—including a hospital, housing project, Salt Lake Hardware and Warehouse, and St. Marks Hospital, Salt Lake City. From 1946 to 1949, he worked on several buildings for the Veterans Administration. [36]

The firm of Cannon and Mullen was well known in the state of Utah. As partners they designed schools, factories, municipal buildings, and churches, primarily in Salt Lake City, and had gained a reputation for solid, professional work. The architects were working in the modern style as early as 1939 when they designed the U.S. Bureau of Mines building on the campus of the University of Utah. The Bureau of Mines facility, now known as the HEDCO Building, is actually many buildings connected by ramps and intended to function as a single entity. Although hardly similar to a visitor center in terms of purpose or program, the HEDCO Building was a high-profile commission and would have been used to demonstrate the firm's skill and modernist design philosophy.

Cannon and Mullen began their employment with the National Park Service in 1958 at Bryce Canyon National Park. Their working drawings for the Bryce Canyon Visitor Center, which was also based on original designs by Cecil Doty, were completed in May 1958. [37] The Bryce and Zion visitor centers are only about twenty miles apart and both share the geography of Utah's canyonlands. Both buildings feature a large auditorium, exhibit room, and lobby for visitors and an office wing for park employees. Despite similarities in climate and program, the two visitor centers illustrate the range of aesthetics contained within the Park Service Modern style. The Bryce Visitor Center is a simple building with a flat-roofed lobby and a double-height auditorium and exhibit area behind. The lobby is distinguished by little more than glass entrance doors and floor to ceiling windows. A standard, single level office wing extends to the north. Doty's red brick building with redwood trim originally featured peaked roofs over the lobby and auditorium. [38] In a second preliminary design completed a few months later, he flattened the roofs, giving the building a more modern, streamlined appearance. After developing a standard plan at Bryce, Doty was clearly more willing to experiment on a design for the more elaborate Zion facility.

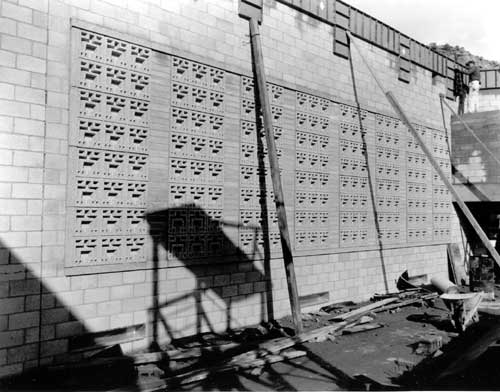

The Bryce Canyon Visitor Center commission gave Cannon and Mullen experience with canyon sites, the Park Service Modern style, and Doty's plans. When nearby Zion National Park required similar services, the firm was eager to continue its park work. The Zion Visitor Center was not Cannon and Mullen's most original commission—the design, after all, had been developed by another architect—but the execution of working drawings and supervision of construction did prove a creative challenge. The firm took Doty's preliminary sketch and construction outline and transformed his concept into a visitor center that could actually be built; the project required thirty-nine sheets of drawings. The major design change consisted of moving the restrooms from inside the lobby to the exterior of the building, where they became part of the facade. This arrangement was common to other visitor centers, such as Doty's facility at Colorado National Monument, and may have been advised by the Park Service. In any case, the as-built lobby proved a more effective space for viewing the surrounding canyon landscape and aesthetically complimented the building's modern style. The firm also attempted to mitigate the severity of the central section by adding cast stone vents along the top and covering the restroom walls with cast stone of a "large" aggregate. By choosing a random stone veneer of dark reds and browns, the architects created a clear contrast to the duller-colored, regular concrete blocks. Cast stone elements were specified for the lobby details, and drinking fountains were designed of native stone.

Bidding on the construction of Zion Visitor Center opened on February 19, 1959. Of the fourteen bids received, the lowest acceptable was submitted by Charles H. Renie of Moab, Utah, who planned to construct the building for $359,032. Renie visited the site in April accompanied by WODC Building Inspector Eugene Mott. By the end of the month, excavation for the footings was underway. The park reported "good progress" on the visitor center in April. The footings for the basement were poured, and reinforced steel forms for the concrete walls were placed. Work began on the South Entrance Road project in July, as Renie poured concrete for the main floor of the office wing. The structural steel and partition work for the office wing was reported as sixty percent complete the next month. When James Mullen made a visit to the building site in early September, he saw masons working on split lava brick and molded rock in several sections of the building and examined the completed concrete floors in the visitor center's comfort station and auditorium. [39]

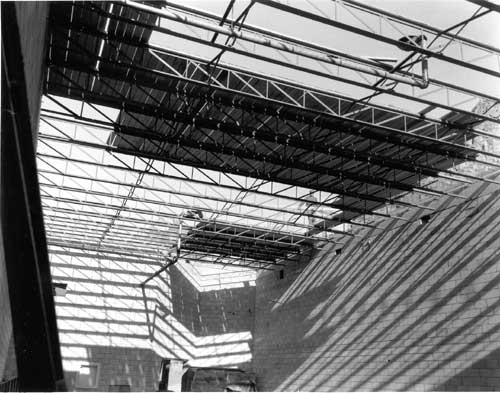

Although progress was still considered excellent in October, the visitor center project was slowed by a steel strike that caused delays in the erection of the steel framework in the lobby. The strike also delayed construction on the steel work for a bridge on the south entrance road. In the meantime, utilities were completed and plasterboard finished in the office wing. By the end of December, the wing had window sashes, oak trim, and a roof, but Park Service supervisors were forced to contemplate substituting aluminum window sashes for steel in the lobby. The completion of the lobby was contingent on the delivery of the aluminum. Although structural steel work inside the lobby and exterior block work was nearly finished, the visitor center remained a roofless shell. Acoustic stone was placed in January 1960, giving the interior of the auditorium an interesting pattern of concrete block contrasting with blocks impressed with an abstract bird motif. By the end of March the job was reported as eighty-five percent complete, and the Park Service estimated a final completion date of May 10, provided that the necessary aluminum sashes arrived. Details of construction included the placing of acoustic tile in the exhibit room and office wing, plaster on the ceiling of the auditorium, and metal lathing on the ceiling in the lobby. On April 6, Cannon visited the building and, according to Acting Project Supervisor W. P. Fairchild, "liked what he saw." Cannon asked that the bright yellow "ceiling molds [sic]" be changed to match the brown walls, an alteration that Fairchild agreed improved an otherwise "gaudy" situation. [40] The aluminum was finally installed. Two days after the final inspection of the visitor center on June 8, the building was opened to visitors. [41]

Figure 82. Zion National Park Visitor Center, exhibit room roof under construction. (Photo by Carl E. Jepson, January 1960. Courtesy Zion National Park Archives.) |

Figure 83. Zion National Park Visitor Center, acoustic stone in auditorium. (Photo by Carl E. Jepson, January 1960. Courtesy Zion National Park Archives.) |

In August, Superintendent Frank Oberhansley, who had replaced Franke in December 1959, reported ongoing difficulties with the visitor center: "lack of exhibits completion, troubles with audio-visual equipment, failure of air-conditioning units, being a few." The museum exhibits were not installed by the Western Museum Laboratory team until the second week of January. Landscaping, irrigation, service roads, and parking areas were almost complete by the end of March. The landscaping was performed "in accordance with Landscape Architect's drawings." [42] Once interior furnishing, exhibits, and equipment were calculated into the price tag, the building cost half a million dollars. The Superintendent may have been unhappy about interior furnishings and mechanical systems, not to mention the overall expense, but he did not complain about the building. In fact, the Park Service was so pleased with the services of Cannon and Mullen that work at three additional Utah visitor centers followed: Timpanogos Cave (1963), Natural Bridges (1965), and Golden Spike (1967).

Figure 84. Zion National Park Visitor Center, northeast terrace under construction. (Photo by Charles McCurdy, May 1960. Courtesy Zion National Park Archives.) |

The Zion National Park Visitor Center was not officially dedicated until June 17, 1961, a full year after it had been opened to visitors. The dedication program, sponsored by a civic group called the Five County Organization, featured a speech by former superintendent and current Park Service Associate Director Eivind T. Scoyen. A press release described the new visitor center as "a 25-room, one-story and basement building of reinforced concrete, structural steel and masonry block, designed to carry out the motif of its general surroundings in the Oak Creek area of the Park." [43] All seven of the park's living superintendents attended the ceremony.

Figure 85. Zion National Park Visitor Center, east elevation. (Photo by Carl E. Jepson, February 1961. Courtesy Zion National Park Archives.) |

The Zion Visitor Center was certainly modern enough to offend critics of Mission 66 and the Park Service's new architectural style. As if in response to those who doubted the suitability of modern architecture in the parks, the National Park Courier reported that the building's "sound architectural planning . . .has kept in mind the purpose of the building and the needs of the visitor . . ." [44] The article went so far as to say that the visitor center looked "as though it belongs in Zion Canyon" and conformed to the topography of the location. This was high praise for a building with a glass-walled lobby enclosed by cantilevered spider-leg steel beams. Perhaps better than most visitor centers, the Zion building illustrates the fact that modern architecture was welcomed in the parks as long as it made some gestures toward the natural environment. Promotional literature suggests that the public welcomed bright new facilities with modern restrooms and auditoriums. Mission 66 visitor centers accommodated both the need for improved services and the equally powerful need for service buildings that complemented their surroundings.

Figure 86. Zion Visitor Center lobby, June 1960. (Courtesy Zion National Park Archives.) |

Although the Zion Visitor Center remains much as it was in the 1960s, today's visitors no longer enjoy the original views of the canyon from the lobby. The once spacious lobby is now overwhelmed by a bookshop that blocks canyon views to the north and east. The shop is a distraction from the outdoors and minimizes the chance that visitors might walk out to the exterior viewing terrace. In photographs taken shortly after construction, the lobby is completely empty except for the information desk, the relief map in the center of the space, and chairs for viewing the surrounding scenery. The lobby's modern character was more apparent in the 1960s, when the unique, translucent viewing area extended from the solid mass of the rest of the building.

Cecil Doty,

Architect

After the official conclusion of the Mission 66 program in 1966, Cecil Doty received the Department of the Interior's distinguished service award and transferred to the Eastern Office of Design and Construction. His main project during this time involved working with Skidmore, Owings and Merrill on the fountains around the Mall. Doty retired two years later. Two oral history interviews were conducted in the mid-1980s, when Doty lived in Walnut Creek, California. [45]

In 1990, the year Doty died, he described one of his "pet peeves"—the fact that as a Park Service employee he was always considered a draftsman, not an architect. [46] Many of the buildings he designed were constructed without his presence; some without his ever seeing the finished product. But in his old age Doty could rest assured that he had made a significant, if largely unheralded, contribution to the National Park System. Doty is the individual responsible for the consistency of design that is the Park Service Modern style. The hand of Cecil Doty influenced nearly every visitor center built, including three of the five featured in this study. In the same way that Doty closely imitated Herbert Maier's work, admiring Park Service architects copied his designs. As we evaluate Mission 66 visitor centers, we should not become too preoccupied with whether or not a building is an original Cecil Doty design. The Park Service Modern style, like Park Service Rustic, was the choice of its day and the work of its generation.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

allaback/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 26-Apr-2016