|

AMISTAD

American Indian Tribal Affiliation Study Phase I: Ethnohistoric Literature Review |

|

Chapter Two:

Ethnohistory, 1535-1750

INTRODUCTION

Ethnohistory relies on documentary material to describe and study groups that lack written history (Trigger 1986; Washburn 1965). It is, however, employed in a broader sense to document and trace the histories of a variety of distinct groups that may or may not lack written history. The NPS defines ethnohistory as "a methodology for obtaining culture-specific descriptions and conducting analyses within a historical framework" (NPS-28 [1997:167]). Elsewhere, the same NPS directive states that it is a "systematic description (ethnography) and analysis (ethnology) of changes in cultural systems through time, using data from oral histories and documentary materials" (NPS-28 [1997:181]). Regardless of which definition is employed, the primary tools for conducting ethnohistoric research are the same: oral histories and documentary materials.

Tracing the original inhabitants of modern Texas is difficult because the ethnohistoric data on them are thin. As a result, our understanding of the human landscape over the past 400 years is poor. The Spanish were the first to arrive and describe what they saw. While their descriptions are important, they saw only pieces of the human landscape and those pieces varied through time. They described modern Texas and much of northern Mexico as "la tierra adentro" or "el interior"—a vast physical landscape, poorly known and little traveled. Throughout the history of Spanish Colonial rule, the geographic boundaries that defined the Texas territory changed markedly, yet most of the modern territory of Texas was still considered part of the Spanish Province of Coahuila (see Weber 1992).

When the Spanish first passed through the macro-region in the early 16th century, they found a large, environmentally diverse landmass occupied by a wide variety of native groups (Wade 1998; Kenmotsu 1994). By 1600, Spain knew that agriculturalists (the Caddo) lived in villages in the far eastern parts of the state and that other agriculturalists resided in the area where the Conchos River of Mexico joined the Rio Grande (known as La Junta de los Rios). Elsewhere, they met coastal groups who were able fishermen dining on the fish and shellfish of the bays and the Gulf of Mexico and feasted on large inland patches of prickly pear cactus whose fruit (tunas) provided another important food resource (Pupo-Walker 1992; Chipman 1987). By this early date, Spaniards had also met some of the hunting and gathering peoples who occupied the area we define as our macro-region, and who traveled the margins of the Pecos River and the Rio Grande (i.e., our micro-region). Over time, the Spanish would learn that la tierra adentro was home to a sizable number of other hunting and gathering groups, and some of those groups became well-acquainted with the Spanish newcomers. Most, however, maintained their distance. Prior to the late seventeenth century, Spaniards found little economic incentive to explore or become better acquainted-with the physical or cultural landscape of modern Texas. South of the Rio Grande, the situation was not much different. Settlements throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth century were few and far between, and "there was not . . . much to attract colonists to a wild, exposed frontier where missions and a few latifundistas controlled the water and the best sites for agriculture" (Gerhard 1993:331-332).

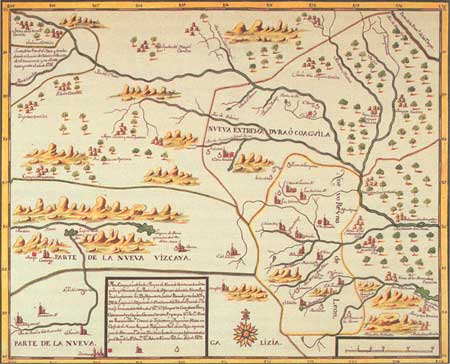

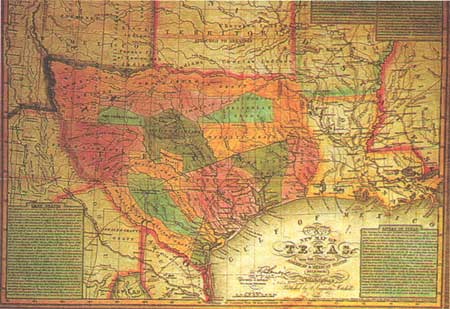

In the late seventeenth century, an area larger than our macro-region was segmented from Nueva Vizcaya [1] to become part of the Province of Nueva Estremadura, an area that encompassed the eastern portions of modern Texas (Gerhard 1993:328). A few decades later, Coahuila, the northern part of Nueva Estremadura, was granted provincial status. Texas remained under Coahuila's control until 1722, when the lands north and east of the Medina River were separated into the Provincia de Tejas (Figure 7). In 1821, Coahuila and Tejas became part of northern Mexico when it won its independence from Spain. Then, in 1836, Tejanos wrested their separation from Mexico and the province became the independent Republic of Texas (Figure 8). Finally, in 1846, Texas joined the United States of America and two years later the portion of Coahuila north of the Rio Grande was annexed to the state.

|

| Figure 8. Map of the Republic of Texas in 1836 (courtesy Texas Department of Transportation). (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Combined, these factors contributed to the dimness of the ethnohistoric record. Spanish maps of Texas, while generally far more reliable than most other maps of the time, contain multiple errors. The errors underscore Spain's limited knowledge of the macro-region, the micro-region, and the occupants of either. In this chapter, we describe the macro- and micro-regions and their environments, offer brief comments on the events that affected the cultural landscape prior to 1881, and finally describe the Native Americans cited in the documents who made up that cultural landscape. Our descriptions focus on Native Americans who can be identified in the micro-region or are thought likely to have been in the micro-region; we also provide our interpretations of the affiliations of those groups with the Amistad NRA. Research completed during Phase 2 of this study or research conducted in future years may arrive at different conclusions. The summary below and the descriptions we offer are based on our completed ethnohistoric research.

THE ENVIRONMENT

Micro-Region

As discussed in the preceeding chapter, the environment of Amistad NRA and its immediate surroundings are what we call the micro-region, and, for consistency, the micro-region equates to the Lower Pecos Archeological Region. The Lower Pecos Archeological Region is defined as that zone "from the greater mountainous area to the west, the Edwards Plateau north and east, and the mesquite savannah of south Texas" that surrounds the confluences of two major rivers—the Pecos and the Devil's—with the Rio Grande (Bement 1989:63-65). As such, the micro-region consists of an area that encompasses all of Val Verde County and parts of adjacent Terrell, Crockett, and Edwards counties. It also extends ca. 100 miles south into Coahuila, Mexico (Turpin 1991:2).

The environment of the micro-region is dominated by three river systems—the Rio Grande, the Devils, and the Pecos—that have down cut through a rugged, relatively flat uplift of Cretaceous limestone. South of the Rio Grande on the Mexican side of the river, a number of smaller streams flow north and northeast into the Rio Grande, but none are of the magnitude of the Pecos or Devils rivers, nor do they travel the distance of either of those streams from their headwaters. Historically, the three major rivers have been called a variety of names. The Rio Grande, which begins in the snowmelt of Colorado's Rocky Mountains and flows south through a relatively flat desert in southern New Mexico and western Texas until its flow is replenished by the Conchos River of Mexico, has been called Guadalquivir, Rio Bravo, and Rio Bravo del Norte. The Pecos, flowing south from eastern New Mexico, has often been called Salado for its high salt content and the Puerco for its turbulent, muddy water. Finally, the spring-fed Devils River, originating in the streams and springs of the southwestern Edwards Plateau, was formerly known as Rio Diablo or Rio San Pedro. The latter confluences with the Rio Grande a short distance above Amistad Dam while the confluence of the Pecos with the Rio Grande is some miles upstream, but also within the Amistad NRA (see Figure 1).

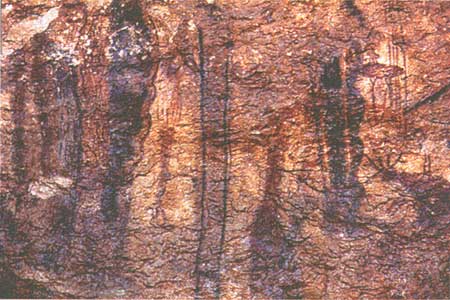

In places, each of the three rivers is confined to relatively narrow channels that have been deeply incised into the limestone strata. The Devils is incised near its mouth; northward, the incising is less pronounced. Downcutting along the Pecos and Rio Grande, in contrast, has been substantial. Where incised, each of the drainages has high bluffs overlooking steep cliffs. Rockshelters, with spectacular vistas of the canyons and tablelands that define the region, have been carved into these cliffs (Figure 9). Some of the rockshelters were occupied intermittently throughout prehistory; others were used to create magnificent, world-renowned polychrome art panels (Figure 10). This art is restricted to the Lower Pecos Archeological Region and is one of the defining features of that archeological region (Turpin 1991). Above the incised drainages, stretches a rolling, albeit dissected, tableland. West of the Pecos, the tablelands are known as the Stockton Plateau (Bryant 1975:3). These same tablelands are also found south of the Rio Grande and extending southward to the Sabinas River in Mexico, which flows southeast out of the Sierra Madre Oriental (Gerhard 1993:326; Bryant and Riskand 1976). Emory (1987:72), traveling south of the Rio Grande in 1854, described that portion of the micro-region as: "an arid, cretaceous plain, covered with a spinose growth similar to that on the Texas side." East of the Pecos and surrounding the Devils, the area is part of the Balcones Canyonlands, a subset of the Edwards Plateau region (Ellis et al. 1995). Since the southern boundary of the Lower Pecos Archeological region is somewhat vague, we use the Sabinas River (Mexico) as the southern boundary of the micro-region and the eastern boundary south of the Rio Grande to be an arbitrary line from the confluence of the San Rodrigo River (of Mexico) south to the modern town of Sabinas, Coahuila. Water is scarce throughout these tablelands and is largely held in small or large karst features (Gerhard 1993:331; Bryant and Riskind 1976:4).

|

| Figure 9. Rockshelters along the Rio Grande (Photograph courtesy Texas Historical Commission). |

|

| Figure 10. Example of polychrome rock art found in the Lower Pecos, site 41VV79 (Photograph courtesy Texas Historical Commission). |

The climatic regime of the micro-region is semi-arid, characterized by low annual rainfall and high evapo-transpiration rates (Gerhard 1993:331; Golden et al. 1982; Bryant 1975). Rainfall, however, is highly variable with a recorded high of 37 inches in 1914 and a low of 4 inches in 1956. Most rainfall occurs during the summer months of July, August, and September, with spring being the driest period of the year. Summer and, at times, spring rains usually arrive in the form of high intensity, albeit localized, thunderstorms. Flashfloods—such as the disastrous event that impacted Del Rio in the winter of 1998—are not unknown. Temperatures are temperate with hot summer temperatures averaging 98°F and mild, dry winters averaging 53°F. Because of consistently high summer temperatures, the evaporation rate on the tablelands of the micro-region is quite high, and the available surface water on those tablelands is minimal. In contrast, rains recharge local springs and tinajas and can significantly increase runoff in the deep canyons during the summer heat.

Given its climatic regime, the vegetation in the micro-region is today dominated by xeric succulents and thorny scrub (Diamond et al. 1987; McMahon et al. 1984). Nonetheless, the dominant plant communities in the micro-region vary somewhat from north to south. In the northern and western portions of the micro-region—the washes and alluvial drainage of the Pecos River and its associated tablelands, including the Stockton Plateau and the lands south of the Amistad NRA—the vegetation is dominated by the Mesquite and Juniper Brush shrub community. As Bryant (1975:2) noted, this vegetation is "almost desert-like in composition." Fourwing saltbush, creosote, lotebush, pricklypear, tasajillo, agarito, yucca, sotol, catclaw, Mexican persimmon, shin oak, sumac, sideoats grama and other grasses, are found in association with these two plants. Saltcedar, a non-native species, is also part of the community. To the east, the northern reaches of the Devil's River drainage are within the Balcones Canyonlands (Ellis et al 1995). There the vegetative regime is known as the Mesquite-Juniper-Live Oak Brush. Plants commonly associated with the regime include sumac, cacti, yucca, sotol, catclaw, lechuguilla, Mexican persimmon, and a number of grasses, and the regime is nearly identical to the Mesquite-Juniper Brush community (McMahon et al. 1984:10; Bryant 1975:2). The heart of the micro-region, however (i.e., the area of the Amistad NRA), is a short grass and shrub savanna whose vegetation type is characterized by the Ceniza-Blackbrnsh-Creosotebush Brush community (Dering 1999; McMahon et al. 1984:8). These species predominate along the river as well as on the slopes of its terraces north and south of the river and also on the slopes of its tributaries. Other prominent species in this plant community include guajillo, lotebush, mesquite, Texas prickly pear, palo verde, goatbush, yucca, sotol, desert yaupon, catclaw, kidneywood, allthorn, and a variety of desert grasses (Diamond et al. 1987; McMahon et al. 1984).

Most soils throughout this micro-region are shallow and calcareous, having largely formed through decomposition of the underlying limestone bedrock (Golden et al. 1982). However, some soils, found on stream terraces and valley fills, are deep. Of these deeper soils, those in the vicinity of the Amistad NRA (the Olmos-Acuna-Coahuila and Jimenez-Quemado series) formed in old alluvium over caliche and limy earth, and are present on ancient stream terraces that are now found in uplands throughout the micro-region (Gerhard 1993:329; Golden et al. 1982:11-12). Other deep soils consisting of recent fine-grained alluvium (e.g., the Dev, Lagloria, Rio Diablo, Rio Bravo, and Reynosa) are on the narrow terraces adjacent to the modern streams and rivers in the region. Prone to flooding, these continually aggrading deposits exhibit little soil development even though they can exceed 15 meters in depth. Individual flood events, such as the one that occurred in 1954, can leave in excess of 50 cm of new alluvium on these narrow terraces (Gustavson and Collins 1998:19-26). Flint—a resource that was frequently accessed by the prehistoric and historic Native Americans who lived in the region—is commonly present in the massive limestone exposed throughout the micro-region.

The summer rains in the micro-region provide water to the deep protected drainages. As a result, the incised canyons have greater floral and faunal diversity than the tablelands (Dering 1999). Oaks, little-leaf walnut, mesquite, native pecan, and hackberry are present along the rivers as well as near major springs. A number of cacti (such as agarita, prickly pear, and tasajillo) are abundant in the micro-region, and short and mid grasses and forbs are also found in moderate quantities ell. These include Mexican sagewort, Texas cupgrass, sideoats grama, hairy grama, red grama, perennial three-awn, and slim tridens (Golden et al 1982:6).

Macro-Region

The environment surrounding the Lower Pecos Archeological Region is similar to the micro-region, but exhibits gradual changes to the east, north, west and south. This broader area, our macro-region (see Figure 4), as noted in the first chapter, is made up of all or parts of the Edwards Plateau to the north, the Rio Grande Plains to the southeast, the Gulf Coastal Plains to the south and southeast in Mexico, the Basin and Range geography to the southwest and west, and the Southern Plains to the northwest. These physiogeographic regions are environmentally diverse. However, they are included here because the Native Americans who occupied or moved through the micro-region between A.D. 1650 and 1880 also traveled, lived, hunted, and/or carried out a variety of activities in those regions. European encounters with these groups were far more frequent outside of the micro-region and the documents relating to those encounters are often the ones that mention their presence in the micro-region. At the same time, historic documents define the complex, sometimes rapidly changing, network of relationships among these groups. In order to better judge the numbers of Native Americans moving through the micro-region, the timing of those movements, the ethnic associations of the individuals in the groups, and, to the extent possible, the motivations and agendas of the people moving north/south through the micro-region, we considered it necessary to expand our research to cover this larger area that we call the macro-region. In fact, it is our opinion that to adequately understand the Native American affiliation with the Amistad NRA, it is essential to be familiar with Native American movements and activities in the macro-region. Below is a cursory review of each of these physiogeographic regions; we refer the interested reader to more detailed studies of each, beginning with the references we employed.

The area known today as the Rio Grande or South Texas Plains lies east of the micro-region (McMahon et al. 1984; Arbingast et al. 1973). Also known as the Mesquite Chaparral Savanna or Middle Nueces Zone, these plains have a semi-tropical climate dominated by a strong airflow from the Gulf of Mexico. Temperatures are warm to hot much of the year, ranging from over 100° F in the summer to the thirties in the winter (Norwine 1995). As shown in Figure 4, the region is drained by the Nueces River, originating in the Balcones Canyonlands of the southern portion of the Edwards Plateau. This drainage, together with its tributary the Frio River, flows largely to the east across a rolling to flat topography dissected by intermittent streams. Vegetation is highly varied, with a mix of woody and grassland species within the savanna environment. Dominant species include mesquite, blackbrush, lotebush, ceniza, guajillo, allthorn, Texas prickly pear, various gramas, purple threeawn, and Texas lantana (McMahon et al. 1984:11-12). Fauna is equally varied and includes the species of the micro-region, as well as those typically associated with the Edwards Plateau and the Gulf Coastal Plain.

North and west of the Rio Grande Plains is the Edwards Plateau physiographic region. This region is characterized by thick layers of uplifted Cretaceous sedimentary rock whose eastern and southern boundaries are known as the Balcones Fault zone (Bureau of Economic Geology 1977). Rainfall in the region varies from 21 inches annually in the southern portions to 30 in the northeastern portion. The vegetation on the Edwards Plateau is dominated by juniper, oak, and mesquite in the parklands with some pinon pines and an understory of mesophytic grasses and shrubs (Bryant 1975:1-3). As one moves west, this vegetative pattern gives way to a Mesquite-Juniper community in association with sumac, prickly pear, tasajillo, agarito, and a variety of dispersed grasses and succulents (McMahon et al. 1984:10), typically present in the mesas and hillsides that dominate those portions of the Plateau. The southwestern margins of the Plateau are known as the Balcones Canyonlands, and are defined by a series of prominent, stream-carved canyons. Elevation in this portion of the Plateau drops from ca. 2,300 feet amsl at Rocksprings in Edwards County to 1,000 feet at Amistad NRA (Bryant 1975:1). This elevational change is accompanied by a drop in annual precipitation, coupled with a corresponding change in vegetation. Thus, the juniper/oak/mesquite parklands of the central portion of the Edwards Plateau give way to oak-juniper savannas with an understore of threeawn and muhly grasses to the south (Bryant 1975:2; McMahon et al. 1984:17, 19).

The Southern Plains, situated northwest of the Edwards Plateau and north of the micro-region, are a southward projection of the Great Plains. They are characterized by a large and relatively flat, elevated tableland where "there are no natural features more than 10 or 20 meters high to break the apparently endless monotony" (Bamforth 1988:131). Water here is only seasonally available in small pluvial lakes and in thousands of small deflation basins, known as playas. Vegetation throughout the tablelands is dominated by short and midgrasses (Diamond et al. 1987:210-211). Shinoak and redberry juniper are some of the few arboreal species, present in places along the margin of the plains, although hackberry, willow, and cottonwood can also be found near reliable water, such as the Pecos River. The Pecos marks the western and southern boundaries of this physiogeographic region. Historically, the dominant faunal species on the Southern Plains were pronghorn antelope, deer, bison, jackrabbit, kangaroo rat, kit fox, and badger. However, the three larger foraging species (pronghorn, deer, and bison) were subject to considerable variation in their numbers due to annual variability in forage (Bamforth 1988:63).

Moving to the south and west, the Basin and Range Physiogeographic Province is quite large and encompasses most of the Trans-Pecos of Texas as well as much of the southwestern United States. The province is defined by broad, north-south trending valleys (some inward draining) that are bordered by small mountain ranges. In the macro-region the valleys are higher in elevation (ca. 3,800 feet amsl) than the elevations in the micro-region (ca. 1,300 feet amsl at Langtry, Texas) (Bryant 1975:4). This province also extends south of the Big Bend of the Rio Grande into Chihuahua and western Coahuila (Gerhard 1993:327) in a roughly northwest to southeast projection. The ranges in the northwestern portion of western Coahuila are relatively small. As one moves south, their elevations rise and the ranges are more closely spaced. Eventually, they come together to form the Sierra Madre Oriental of Mexico. Floral resources in the portion of the province just to the west of the Pecos and south of the Southern Plains are generally part of the Desert Grassland community (Diamond et al. 1987:204-205). Dominant species include lechuguilla, creosotebush, grama and other grasses, scrub oak, mountain mahogany, mesquite, creosotebush and sotol. In places, large grasslands (e.g., the Marfa Plains) are present, known as the Tobosa Black Grama Grasslands (McMahon et al. 1984:4), and, at high elevations in the small ranges, woodland floral communities can be found as well (Diamond et al. 1987:207). Faunal resources include deer, skunk, mountain lion, raccoon, jackrabbits, cottontail rabbits, raptors, snakes, toads, and a variety of birds.

The Bolson de Mapimi, located on the eastern edge of the Basin and Range Province and our macro-region, is part of the broader Chihuahuan Desert Physiogeographic Province. The Bolson is south of Big Bend and the Rio Grande canyonlands and east of the Rio Conchos/Rio Florido. An inward draining basin that tilts north and east, most of its scarce surface water is found in lakes that are intermittent and, thus, often unreliable (Gerhard 1993:330; Griffen 1969:1-3). Outside of the Rio Nazas, water is available in the Bolson only seasonally except for a narrow band along its border with the Rio Grande. Floral resources are not abundant, and generally mirror those of the Basin and Range province in the Trans-Pecos region. The aridity of the region, as well as its lack of important mineral deposits, were recognized by the Spanish early in their occupation of Nueva Vizcaya and Coahuila, causing them to generally avoid or ignore these lands. It is singled out here because, as Griffen (1969:1) notes, the Bolson "served as a convenient refuge area for disaffected natives." While Griffen was concerned with the period prior to 1750, there is ample evidence that the Bolson continued to serve as a refuge area through the nineteenth century (cf., Winfrey and Day 1995, Vol. 4:229).

In summary, we intensively researched several archives for documents dealing with a micro-region that corresponds to the Lower Pecos Archeological Region (Hester et al. 1989; Turpin 1991). This region includes the lands of the Amistad NRA and the tablelands that surround it. We were also concerned also with a larger geographic area that we call the macro-region. The macro-region is an arbitrarily defined zone that includes portions of the Rio Grande Plains to the east-southeast, the Edwards Plateau to the northeast, the Southern Plains to the northwest, and the Basin and Range geography that lies to the northwest, west, and south-southwest. The Basin and Range physiography continue to the south of the Rio Grande, eventually becoming the Sierra Madre Oriental, and is bordered on the east by part of the Gulf Coastal Plains. This larger macro-region (see Figure 4) was defined because documents related to the Native Americans who occupied or moved through the micro-region between A.D. 1650 and 1880 were often described during encounters with those groups outside of the micro-region. Therefore, the macro-region was defined to capture these data.

Native Use of Resources

Prior to leaving this section on the environment, a few additional comments are warranted because the construction of the Amistad Dam and Reservoir in 1969 altered the environment of the area under study. The environmental changes caused by the completion of the Amistad Dam and Reservoir together with the inevitable consequences of the historic agricultural and animal husbandry practices considerably modified the distribution of prehistoric, protohistoric, and even early historic resources. Since the analysis of the environmental changes that occurred in the area is beyond the scope of this study, the following comments focus only on some of the resources that impacted the lives of the earliest native peoples in the micro-region.

Native Use of Faunal Resources in the Micro-Region

The panoply of faunal resources utilized by native groups was undoubtedly vast, but the recorded evidence stresses the importance of deer and, most importantly, buffalo. The evidence is quite overwhelming for the presence of vast herds of buffalo immediately north of the Rio Grande in Kinney, Maverick, Uvalde and Val Verde counties between the 1670s and the early 1700s. At that time, it appears that buffalo were most prevalent in those areas between late November and late May. Because of their presence, several native groups, who lived part of the time south of the Rio Grande, traveled north of that river to hunt and establish rancherias in the area (see Wade 1999a). Other groups, who appear to have inhabited areas immediately north of the Rio Grande, also hunted buffalo within the narrow corridor between the Nueces and the Rio Grande rivers as well as in the Rio Grande Plains. There is evidence that resource competition, particularly access to buffalo herds, caused serious conflicts among native groups before the beginning of the eighteenth century (see Wade 1999a, 1999b).

After the 1720s, the buffalo range was altered somewhat. Frequent travel by the Spanish along the established routes near Del Rio and Eagle Pass and south of the Edwards Plateau appears to have disrupted the normal patterns of the buffalo herds and led them to disperse slightly northward and perhaps west of these routes. For example, Berroteran (AGN 1729), during an attempt to find passage from Coahuila to La Junta de los Rios, noted the presence of Apache in the micro-region (see Appendix 4). When approached, the Apache said that they were in the area to hunt buffalo. However, the historical documentation on the Apache and, later, the Comanche indicate that buffalo continued to be present between the Rio Grande and the Nueces rivers (Wade 1998:349-352, 358-360). Prior to 1780, the importance of the buffalo as a material and social resource for the Apache, the Comanche, and other native norteno groups cannot be overemphasized. Most conflicts between these groups that were reported by the Spaniards took place during buffalo hunts (carneadas) (Wade 1998:349-351, 359-360). Moreover, the importance of the buffalo for these native groups as a multi-faceted resource is well known (e.g., Kavanagh 1996; Ewers 1985).

Thus, within the micro-region, annual or biannual access to the animals provided native people with far more than meat: it supplied marrow, fat, rendered fat, pelts, sinews, glue, containers, and other byproducts. Given these various uses, the difficulty or ease with which a group could locate and hunt the buffalo had profound implications for a group's material life. It also deeply affected their social life because it fostered (or forced) some groups into alliances with other groups, putting a premium on friendships and enmities (Wade 1998:388-391). Importantly for this study, the presence of buffalo in the micro-region encouraged certain Native American groups to travel to and/or exploit the micro-region.

Native Use of Floral Resources in the Micro-Region

The evidence in the documents for the use of floral resources in the micro-region is abundant, but the details about specific resources are often scarce. Unlike resources on the hoof, stationary vegetable resources are far easier to control and exploit. The most frequently mentioned resource is the prickly pear and its fruit, the tuna. Depending on the physical location, the pricklypear was the resource of choice between June and November. Other resources often mentioned are mescal, roots, roots of reeds, and nuts.

The importance of these resources is often detected through indirect means. For example, the records of the 1670s (Wade 1999a, 1998:405) indicate that some conflicts occurred because native groups crossed resource boundaries in the micro-region, and some of these conflicts were over the pricklypear. There are several other instances of recorded alliances and war coalitions being made during pricklypear gathering season in the macro-region (Portillo 1984:157-159; Cabeza de Vaca 1971:55-56). In 1683, Juan Sabeata (Wade 1998:412; AGN 1683) specifically said that the groups who were allies of the Jumano utilized the nut resources in their lands, generally located to the north in the macro-region along the tributaries of the Concho River of Texas (Kenmotsu 2001). From these statements, it is clear that members of the Jumano coalition (some of whom were from the micro-region) were given the right to access those resources and that such right was part of the privileges and responsibilities shared by the members of their coalition. From these and other examples, it is apparent that floral resources served as both subsistence and social resources and that alliances and coalitions were closely tied to particular gathering seasons.

Through time, the use of floral resources by native groups continued to be mentioned in the historical records. As late as 1856, Assistant Surgeon General Wyllie Crawford (1856:392) stated that native people often lived for days solely on pecans. Native Americans and Anglo-Americans alike used these resources for other purposes. The reports of the Army Surgeon in the information compiled for the United States on the military forts in the Rio Grande area (Head 1855:349-353; Perin 1856:360-363) mention the use of agave (maguey or Agave Americana) as a cure for scurvy. Several experiments with positive results were made using agave juice as a cure for scurvy, a disease that afflicted the soldiers. Perin (1856:363) described the manner in which the agave plant was prepared, noting that the juice of the maguey was said to be very rich in saccharine and capable of sustaining a patient for days. In 1854 Byrne (1855:58) also described the preparation and use of the maguey plant by the Apache:

The lower and sound portion of the plant (not the root) is divested of all the leaves, stalk, &c., then placed into a hole dug in the ground, covered completely with earth to the depth of an inch, and over all there is built a good but slow fire. It requires from twelve to eighteen hours to cook it thoroughly; when cooked thus it is extremely pleasant to the taste, and is a capital substitute in the absence of all other vegetables; indeed, it is the only diet of this nature that these Indians (sic) possess. The other way of cooking it is to pound or mash it up, and boil it until it becomes thick. This is also very palatable and nutritious.

Crawford (1856:392) mentioned the use of wild lamb lettuce (fedia radiata) and pokeweed (phytolacca decandra) as other cures for scurvy. Given these data, it seems reasonable to assume that plants such as the agave provided native groups with tasty, nutritious food probably high in vitamin C since the juice of the plant was the preferred remedy for scurvy by American army doctors.

SUMMARY OF NATIVE AMERICAN

HISTORY

(1535-1750)

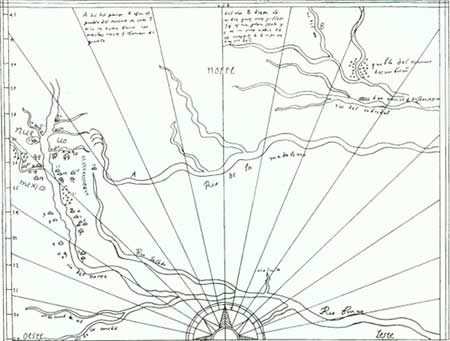

The history of native groups in Texas began at a time when the modern territory of Texas did not exist, politically, as a separate province of New Spain, and when Spanish and American awareness of the physical and cultural geography of the land was sketchy (Figure 11). To counteract the modern tendency to visualize the geographic expanse of Texas with its present political boundaries, it is necessary to conceive of the Texas territory in the 1670s as the eastward continuum of the province of Nueva Vizcaya and the frontier lands of the incipient province of Coahuila (then Nueva Extremadura, see Gerhard [1993:328]). For the Spaniards of the late seventeenth century, the Rio Bravo del Norte (Rio Grande) marked the boundary of a vast wilderness that stretched east of New Mexico. On the other hand, archival documents indicate that the micro-region was the theater of intensive interaction between native populations (Wade 1999a). This interaction involved extensive buffalo hunting and considerable south-north traffic across the Rio Grande at preferred river crossings. Although the actors changed from 1535 to 1750, some of these patterns of interaction continued and specifically involved the lands of the Amistad NRA.

|

| Figure 11. The general area of Texas, New Mexico, and southern Oklahoma on a map drawn ca. 1602 by the Spanish cartographer Enrico Martinez from information obtained from a member of the Oñate's explorations of those lands (traced from the original as depicted in Wheat 1957:83, map 34). |

The historical records that relate to the modern state of Texas began with the shipwreck of Cabeza de Vaca and his companions (1528-1535), and continued with the expeditions of Coronado (1540), De Soto-Moscoso (1542-1543 in Texas), Chamuscado-Rodriguez (1581-1582), Espejo-Luxan (1582-1583) and Castaño de Sosa (1590). Those travelers and expeditions saw different pieces of the modern territory of Texas and acquired different perspectives of it. Most were just passing through on their way to somewhere else. From Cabeza de Vaca, Espejo, and Luxán, however, it is possible to learn some important information about the macro-region's environment and some details about the native peoples. Castaño de Sosa (1871) entered the micro-region and passed through the Amistad NRA, but the evidence he provided about native groups is quite sparse except for his brief statements about the Despeguan or Tepeguan groups met near the Val Verde-Crockett County line.

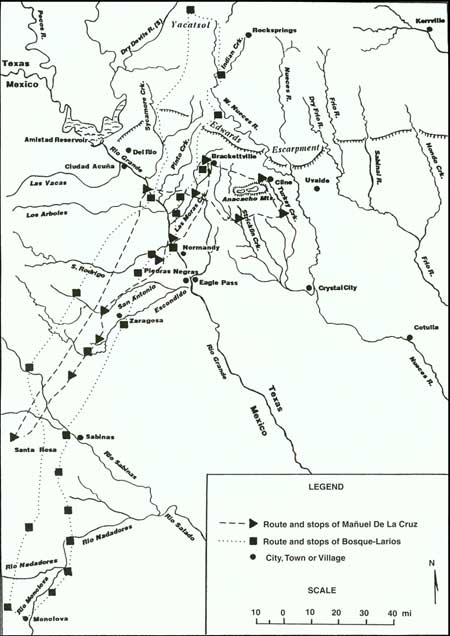

As the evidence stands, therefore, it is not until the records from the mid-seventeenth century from the areas of Saltillo and Monclova that important early information about Native American groups in the micro-region began to be available. These records clarify the relationships and interactions between several of these groups, their modes of subsistence and the reasons that led to the trips north of the Rio Grande by Fr. Manuel de la Cruz (1674), Fr. Francisco Peñasco (1674), and the Bosque Larios expedition (1675). They refer specifically to the micro-region and also to Amistad NRA. Below, we provide a brief summary, highlighting such relationships or key historical events that held ramifications for the individual groups that occupied and/or used the micro-region, beginning in the 1670s and continuing at specific key points in time.

Narrative of Events 1673-1675

(Wade 1998:38-139, 1999a, 1999b)

In 1673, Fr. Larios and other Franciscan friars established several mission settlements for a large number of natives groups in northern Coahuila on the southern fringe of the micro-region. These settlements were in response to the friars' desire to convert the natives as well as the natives' wish for settlements. Not surprisingly, both the native groups and the friars held different expectations of what the settlements would be like and how they would operate. Lack of adequate food supplies, disease and the need to procure sustenance led several of the native groups to repeatedly abandon the settlements. On one of those occasions, in March 1674, Fr. Larios ordered Fr. Manuel de la Cruz to travel to the north side of the Rio Grande to contact the Gueiquesale and the Bobole. Fr. Manuel de la Cruz crossed the Rio Grande a short distance below modern Del Rio and traveled eastward for three days (see discussion of this trip in Wade [1999a]). While on that path, Fr. Manuel and his five Bobole companions were intercepted by a native who warned them not to continue in that direction because the Ocane-Patagua and the Catujano were determined to capture the friar. Fr. Manuel hid in an arroyo until his Bobole scouts had located the Bobole rancheria. He then veered northward and reached the Bobole rancheria where he learned that the Gueiquesale were about 20 miles further inland. While at the Bobole rancheria, Fr. Manuel was visited by Don Esteban, the Gueiquesale spokesperson, who, having learned of the predicament of Fr. Manuel, was accompanied by 99 of his warriors, prepared for war. Later reports from Fr. Manuel and Don Esteban indicate the conflict also involved the Ervipiame and their allies and that one of the reasons for the conflict was that Fr. Manuel was trespassing into Ervipiame's lands. Whatever the real reasons for the animosity, it appears that it began before Fr. Manuel's trip and continued into 1675.

Soon after Fr. Manuel's arrival, native scouts reported that enemies were approaching, intent on war. The combined force of 147 Gueiquesale and Bobole warriors, accompanied by Fr. Manuel, proceeded to the locale where the battle took place. The Gueiquesale-Bobole party was victorious, killing seven people and capturing some women and children. The Ervipiame and their allies took flight hiding in the place the local natives called Sierra Dacate. After the battle, the victors returned to the Bobole rancheria and then joined the remainder of the Gueiquesale rancheria. Together, they returned to the mission settlement of Santa Rosa de Santa Maria near the Rio Sabinas, north of Monclova, Mexico, ca. 130 miles south of Del Rio.

The exact determination of Fr. Manuel's route is hardly without problems because the friar provided scant details. However, it is possible to state that, in all likelihood, he crossed the counties of Maverick, Zavala, Uvalde and Kinney—all immediately east of the Amistad NRA but still within the micro-region (Figure 12). Fr. Manuel described the country he traveled through as beautiful plains with abundant buffalo and watercourses teaming with fish, turtles, and crayfish. The reports of the Franciscan friars in 1674-1675 leave no doubt that these native groups had individual populations who were as small as perhaps 100 individuals and as large as 500 individuals or even more.

Several months later, in May 1674, Fr. Larios ordered Fr. Francisco Peñasco to travel to the north side of the Rio Grande to persuade another group, the Manos Prietas, to return to Santa Rosa. The Manos Prietas had left the area of Santa Rosa to hunt buffalo north of the Rio Grande. Fr. Peñasco crossed the Rio Grande and found the Manos Prietas about 10 miles north of that river, well provisioned with buffalo meat. While with the Manos Prietas, Fr. Peñasco was told about another group, the Yorica, who were located 20 miles further inland. Fr. Peñasco then contacted the Yorica, who responded that they were not interested in leaving "their" lands where they had plenty of food to eat. Fr. Peñasco sent a second ambassador to make an offer of settlement, which included oxen and seeds to plant. Persuaded by this offer, the Yorica returned with Fr. Peñasco and the Manos Prietas to the settlement of Santa Rosa.

Despite valiant efforts on both sides, the mission settlements of Santa Rosa and San Ildefonso enjoyed only limited success. The flimsy structures of Santa Rosa were burned sometime in June or July of 1674. Following this event, the native groups congregated elsewhere in the surrounding micro-region. Several spent part of the year north of the Rio Grande in the counties immediately surrounding modern Amistad NRA. It should be noted that because the friars followed the native groups as they shifted from place to place in search of localized food resources, the friars continued to congregate many groups in several areas and to establish temporary settlements in the area of modern Coahuila and our micro-region.

In November 1674, Don Antonio Balcarcel de Ribadeneyra y Sottomayor took possession of his post as Alcalde Mayor of the city named Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, later called Monclova. Balcarcel planned to establish several pueblos for the native groups, particularly for the Bobole, the Gueiquesale, and the Catujano. Balcarcel's intent to establish settlements was fortuitous for the native groups. It tapped into the attempts made in Saltillo by some groups (since at least 1658) to do exactly this (Wade 1999a:58). Among the groups involved in these early efforts to establish autonomous native settlements were the Jumano.

However, Balcarcel appears to have been unprepared for the overwhelming number of native groups who wanted to profit from the offer for settlement. Balcarcel did not have the resources to establish pueblos for all who wanted to settle and was unable to obtain further help from the Spanish Crown for that purpose. He established only one pueblo for the Bobole and the Gueiquesale: the pueblo of San Miguel de Luna near modern Monclova. In an effort to stem the movement of groups into Monclova, Balcarcel ordered his lieutenant Fernando del Bosque, together with Fr. Juan Larios, to travel to the north side of Rio Grande to survey the land, count the people, and tell them not to move into Monclova, but to wait in their lands until the King decided if he would grant their request for settlement.

At the end of April 1675, Fernando del Bosque and Fr. Larios traveled to the north side of the Rio Grande where they met native groups who were living in the area. Several groups complained about difficulties in traveling to find the buffalo herds and to visit their kinfolk. Among the groups who complained were the Ape (Jeapa), Bibit (Mabibit), Geniocane, Jumee, and Yorica. The Bagname and the Siano (Sana) were probably in the same situation. However, other groups who were living in the area and were allied with the Gueiquesale seemed not to experience these difficulties, perhaps because the Gueiquesale and their allies controlled access to strategic areas such as the edge of the Edwards Plateau and the plains south of the Plateau's escarpment.

Bosque ordered all the groups north of the Rio Grande to stay in their lands and to remain at peace. He pointed out that there were serious conflicts among them. The Gueiquesale and their allies were at war with the Geniocane; the Yorica, Jumee and Bibit were at war with the Arame, the Ocane and their allies, and the Bobole were at war with the Ervipiame. Similar comments were made by Balcarcel in a letter he wrote to the Audiencia de Guadalajara a few months later (Wade 1999a:43). Balcarcel made it explicit that these conflicts resulted mainly from differences of opinion about access to resources, particularly buffalo. In 1674 Captain Elizondo, at the bequest of Fr. Larios, had made similar statements. According to Elizondo, native groups defended their access to buffalo herds by the force of arms.

Table 1. Native groups living north of the Rio Grande in the 1670s.

|

Bagname Ervipiame Gueiquesale Mabibit Patagua Teaname Xoman |

Catujano Geniocane Jumee Ocane Siano Terecodam |

During his trip (see Figure 12), Bosque traveled the micro-region through Kinney and Edwards Counties, northeast of the Amistad NRA. All the native groups he encountered were living in that general area. Table 1 shows the groups who, at this time, lived north of the Rio Grande or appear to have spent most of their time in that general area. Some of these likely lived within the Amistad NRA. These groups appear not to have spent much time south of the Rio Grande. The Yorica were living north of the Rio Grande when they were first encountered. Although the Yorica joined other native groups near Monclova at the request of the friars, they continued to spend time north of the Rio Grande. Some of their members may have remained north of the Rio Grande. Other groups such as the Bobole and the Manos Prietas stayed mostly south of the Rio Grande although they spent a considerable amount of time hunting buffalo north of the Rio Grande.

Four main points emerge from the records of this early period, which relate specifically to the area of the Amistad NRA and the micro-region:

1. The area of Maverick, Kinney, Edwards, Zavala, Uvalde, and Real counties, and the southeast corner of Val Verde County were the focus of intensive interaction between native groups who lived south and north of the Rio Grande. Some specific groups formed coalitions and battles were fought between different coalitions, apparently because of problems relating to trespass or access to resources, particularly the buffalo.

2. The evidence indicates that some buffalo herds traveled south from the Southern Plains through a narrow corridor between the western Nueces and Devils rivers. These herds appear to have reached the Rio Grande valley around January and to have remained in the area until late May. Bamforth (1988) notes that this type of herd dispersion prevailed throughout most of the bison range south of the Great Plains. Several native groups were reported to have hunted in the Rio Grande valley during the early period. Conflicts between native groups sprang from access to buffalo in the lands where they could be hunted.

3. It appears that some coalitions of groups, such as the Gueiquesale and their allies, were attempting to displace other coalitions of groups such as the Ervipiame and their allies during the early period. It is not yet clear whether these conflicts were pitting groups from south of the Rio Grande against groups north of the Rio Grande.

4. The area of Del Rio was a favored river crossing point; it continued to be a favored crossing through time.

1680-1690

The decade between 1680 and 1690 provides several disjointed pieces of information about native groups in Texas in general and the area of the micro-region in particular. During this period, several key events affected both colonizers and the colonized. As the decade progressed there was a shift in the Spanish presence in northern New Spain. During the Great Northern Revolt (see Hadley et al. vol. 2 1997:13), Spain temporarily lost New Mexico in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, and the New Mexican officials established headquarters in exile at El Paso. At the same time, the northeastern frontier (later known as Coahuila) was moved north of the Rio Grande when Alonso de León crossed the Rio Grande to check on the reported French presence on the Gulf Coast and to establish the first military and religious Spanish outposts within Texas territory. These two seminal events made the Rio Grande between El Paso and modern Brownsville the fulcrum of the activities relating to Texas.

The threat posed by the French to the uncolonized Texas territory unraveled with the departure of Sieur de la Salle from the Matagorda area, his murder, and the destruction of the French settlement on the Texas Gulf Coast (1685-1687). Intentionally or not, some native groups had done the Spanish a favor by destroying the French settlement. Thus, the documents from this decade show very clearly the intensive interaction and information exchange between native groups inhabiting the macro-region of the Rio Grande, the Spanish at Monclova, Saltillo, Parral, and El Paso, and the native groups occupying Central and East Texas. Each group acted on such knowledge.

1691-1721

At the end of the seventeenth century the Spanish frontier was moved de facto to East Texas and later withdrawn to San Antonio. The establishment of the Presidio de San Juan Bautista in 1701, and the move of the missions of San Francisco Solano, San Juan Bautista and San Bernardo north to the Rio Grande, made the area to the southeast of Del Rio (part of the macro-region) the center of Spanish military and religious activities in Texas. Those activities brought or attracted several native groups who may or may not have been previously associated with that portion of the macro-region. These groups (Apache, Ape, Catujano, Ervipiame, Jumano, Jumee, Manos Prietas, Mescal, Mesquite, Ocane, Pachale, Pacuachiam, Papanac, Paragua, Pasti, Saesse, Teimamar, Terocodame, Tilijae, Xarame and Yorica, among others) moved in and out of the missions: some because they needed temporary protection, others because they were genuinely attracted to settlement life, and still others because they wanted to profit from the trade opportunities that the proximity of the Spanish provided.

The attractiveness of certain Spanish goods, particularly horses, made any Spanish settlement a magnet for native groups. But, as important as the trade in goods was the trade in information. This was vital to native groups. Information about Spanish activities and troop movements had to be obtained at the principal hubs and information centers of settlements: presidios and missions. Natives in missions and presidios acquired knowledge about Spanish customs, language, expeditions, military campaigns, and supply convoys. They also became closely acquainted with the leading figures in the church and the military. In their essential roles as guides, informers, translators, advisers, and soldiers, native individuals held a good measure of control over what the Spanish knew and how they acted on that knowledge. Until the 1720s and the post-Aguayo period, the Rio Grande area with its presidios and missions continued to be the primary link with the Spanish settlements north of the Rio Grande and the main point for resupplies.

While the Spanish were becoming acquainted with groups native to the macro-region, the human landscape was in a state of flux. During this period, a powerful newcomer—the Comanche—was moving into the region north and northeast of Santa Fe (as early as 1706) and would eventually dominate the Southern and Rolling Plains regions of Texas (Kavanagh 1996; Kenmotsu et al. 1994). One result of the Comanche intrusion into the state was that Apache groups, believed to have occupied the Southern Plains when the Spanish first arrived, were pushed south and east into the macro- and micro-regions, in turn affecting the native groups who had occupied those regions (Wade 1998; Kenmotsu 1994).

After the fiasco to colonize East Texas and bring Caddoan groups out of French influence and into the fold of the Spanish (1689-1694), the eastern Spanish frontier, in real terms, returned to the Rio Grande. Most of the information we possess about native groups in Texas during the last decade of the seventeenth century and the first decades of the eighteenth century comes from the Rio Grande settlements and the expeditions that crisscrossed the territory of Texas during those decades. The Ramon (1716) and Aguayo (1718-1722) expeditions represented a reversal of this pattern. In fact, the political and financial commitment of the Marques de Aguayo to the project to settle Texas led to the enduring establishment of Spanish settlements in East Texas and in San Antonio.

1722-1750

With the establishment of the settlements in East Texas and San Antonio, the Spanish frontier moved to the heart of Texas (see Figure 4). With the move of Native Americans from Mission San Francisco Solano to San Antonio and with the presidios in East Texas and San Antonio fully operative, the relevance of the area of the Rio Grande to the Spanish, including areas of Amistad NRA, was diluted for several decades. During this time, the missions of San Juan Bautista and San Bernardo did not have large numbers of natives (see Appendix 1), and the Rio Grande Presidio became a way station rather than the hub it had been previously.

The documents indicate that, by the onset of the 1730s, the East Texas Caddoan groups were interested in maintaining a relationship with the Spaniards, but only under certain conditions which did not include the acceptance of mission life. Thus, in 1731, three missions previously established for the Caddoan groups were moved to San Antonio: Mission Nuestra Señora de la Puríssima Concepción de Acuña, San Juan Capistrano, and San Francisco de la Espada. The addition of these missions, the development of San Antonio's military and civilian settlement, and their progressively increasing self-sufficiency diminished the reliance on the Rio Grande presidio for supplies and military support. Although the Rio Grande presidio continued to provide some support to the new settlement and was the stopping point for all the traffic in the macro-region between New Spain north and south of the Rio Grande for some time, San Antonio became the new administrative and military focus even though Los Adaes remained the capital.

Against this background, the ethnohistoric data show that certain Native American groups either inhabited or used the micro-region and the Amistad NRA during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (Table 2). Some of these groups were first mentioned and encountered in the area immediately north or south of the Rio Grande area during the late 1600s, and several remained in and around the Amistad NRA through the mid-1700s. During the later period, most of the individuals from these groups were recorded as members of the three Rio Grande missions: San Bernardo, San Francisco Solano, and San Juan Bautista. These groups include the: Ape, Catujano, Ervipiame, Jumano, Jumee, Manos Prietas, Mescal, Mesquite, Ocane, Pachale, Pacuachiam, Papanac, Paragua, Pasti, Saesse, Teimamar, Terocodame, Tilijae, Xarame, and Yorica. Of these groups, the following were first mentioned or encountered north of the Rio Grande in the vicinity of the Amistad NRA: Ape, Catujano, Ervipiame, Jumee, Mescal, Mesquite, Ocane, Saesse, Siano (Sana), Teimamar, Terocodame, and Yorica. It appears that the Yorica, Catujano and Tilijae should be primarily associated with the north side of the Rio Grande because, as of this date, the first known records indicate that these groups and their allies inhabited areas north of the Rio Grande. It is likely that members of all these groups remained in the area, but chose to be outside of the influence of the missions and constituted a nucleus of fluctuating population. One of the strongest indications that this was the case is the frequent recording of marriages between mission natives and individuals shown to be of the same ethnic group, but who were registered as gentile (non-baptized), often without a name.

Table 2. Native Groups who inhabited or used the Amistad NRA during the 17th and 18th centuries.

| Native Grp. | Year | Month | Location | County |

| Apache | 1683 | N and E Pecos River | Upton | |

| Apache | 1684 | N and E Pecos River | Upton | |

| Apache | 1690s | N & W Colorado River | ||

| Apache | 1691 | West of the Tejas | ||

| Apache | 1702-1704 | Mission Solano | ||

| Apache | 1704 | request peace in El Paso | ||

| Apache | 1712 | La Junta de los Rios | ||

| Apache | 1717 | W Colorado River | ||

| Apache | 1719 | Missouri River to Red River | ||

| Apache | 1722-1723 | raids S of San Antonio | ||

| Apache | 1723 | N San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1726 | Nueces River | ||

| Apache | 1729 | border lands of Mansos | ||

| Apache | 1732 | N San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1736 | attacks at San Antonio | ||

| Apache | 1737 | attacks at Rio Grande | ||

| Apache | 1739 | near San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1741 | asked for missions | ||

| Apache | 1743 | displaced by Comanche | ||

| Apache | 1743 | at war on Rio Grande | ||

| Apache | 1743 | Ypandi near Béjar | ||

| Apache | 1745 | N San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1746 | asked for missions | ||

| Apache | 1748-1749 | Guadalupe River rancheria | ||

| Apache | 1749 | Peace Treaty San Antonio | ||

| Apache | 1750 | San Juan Bautista Rio Grande | ||

| Apache | 1750 | Mission S. Lorenzo-Coahuila | ||

| Apache | 1753 | San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1753 | Rio Grande | ||

| Apache | 1755 | San Antonio & at Rio Grande | ||

| Apache | 1755 | San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1757 | San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1757 | Tejas attack Apache on the Colorado | ||

| Apache | 1761 | Upper Nueces | ||

| Apache | 1762 | Upper Nueces - 10 different divisions | ||

| Apache | 1764 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Apache | 1764 | Upper Nueces - smallpox | ||

| Apache | 1767 | Las Moras Creek | ||

| Apache | 1767 | San Fernando de Austria | ||

| Apache | 1767 | Rio Grande rancherias | ||

| Apache | 1770 | 4 | Julimenos & Apache on the Rio Grande | |

| Apache | 1773 | 11 | Delaware Mountains (?) | |

| Apache | 1773 | O'Conor's Treaty with Lipan | ||

| Apache | 1775-1976 | San Saba | ||

| Apache | 1776 | S. Pedro River-tributary of the Pecos | ||

| Apache | 1776 | Guadalupe Mnts, Sierra Blanca & Pecos | ||

| Apache | 1787 | Mescalero at El Paso & E of Pecos | ||

| Apache | 1787 | Sierra del Carmen | ||

| Apache | 1787 | 12 | Hunting on S. Pedro River | |

| Apache | 1788 | 4 | Lipan at San Antonio | |

| Apache | 1788 | 7 | Nueces River | |

| Apache | 1788 | 11 | Pecos River | |

| Apache | 1789 | 8, 12 | Piedras Negras | |

| Apache | 1789 | Frio River | ||

| Apache | 1790 | 4 | Guadalupe Mountains | |

| Apache | 1790 | 10 | Nueces River | |

| Ape | 1675 | 5 | SW Edwards Plateau | Maverick |

| Ape | 1686 | 5 and 6 | SW Edwards Plateau | Maverick |

| Ape | 1686-1687 | Guerrero & Del Rio | Val Verde | |

| Ape | 1689 | S Rio Grande near Guerrero | ||

| Ape | 1690 | S Rio Grande near Guerrero | ||

| Ape | 1693 | S Rio Grande near Guerrero | ||

| Ape | 1700 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Ape | 1706 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Ape | 1708 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Ape | 1708 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Ape | 1726 | Coahuila | ||

| Ape | 1734-1772 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Bagname | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Bibit (Mabibit) | 1674 | 5 | SW Edwards Plateau | |

| Bibit (Mabibit) | 1675 | 5 | Las Moras-Cow Crks | |

| Bobole | 1673 | Saltillo | ||

| Bobole | 1674 | Kinney County | ||

| Bobole | 1674-1675 | Sabinas River and Monclova | ||

| Cacaxtle | 1663 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Cacaxtle | 1665 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Cacaxtle | 1674-1675 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Cacaxtle | 1693 | S bank Rio Grande | ||

| Catujano | 1674-1675 | S Rio Grande near Sabinas River | ||

| Catujano | 1674-1675 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Catujano | 1690-1698 | Mission Candela | ||

| Catujano | 1722 | Mission Candela | ||

| CanoCatujano | 1726 | Mission Candela | ||

| Catujano | 1734 | Mission Candela | ||

| Cholome | 1640-1645 | Conchos River (Mex) | ||

| Cholome | 1726 | Pecos River | ||

| Cibolo (Sibolo) | 1688-1691 | Lower Rio Grande and Pecos | ||

| Cibolo (Sibolo) | 1690-1691 | Sonora | ||

| Cibolo (Sibolo) | 1716 | 5 | Colorado River (beadwaters) | |

| Cibolo (Sibolo) | 1726 | Coahuila | ||

| Cibolo (Sibolo) | 1726 | N. Vizcaya | ||

| Ervipiame | 1674 | 5 | ca. Edwards County | |

| Ervipiame | 1675 | N Rio Grande-Edwards Plateau | ||

| Ervipiame | 1688 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Ervipiame | 1692-1693 | Monclova area | ||

| Ervipiame | 1698 | NW Monclova | ||

| Ervipiame | 1706 | San Francisco. Solano | ||

| Ervipiame | 1708 | N Guerrero | ||

| Ervipiame | 1716-1717 | W Trinity River | ||

| Ervipiame | 1716 | 5 | NNE Colorado River | |

| Ervipiame | 1716 | 5 | near S Gabriel River | |

| Ervipiame | 1716 | 5 | Colorado River (headwaters) | |

| Ervipiame | 1717 | Presidio del Norte | ||

| Ervipiame | 1718 | Presidio del Norte | ||

| Ervipiame | 1721-1722 | San Antonio area | ||

| Ervipiame | 1747 | Rancheria G/S Gabriel | ||

| Ervipiame | 1784 | San Antonio Valero | ||

| Gediondo | 1683-1684 | 1 to 6 | NE Pecos River (ca. Iraan) | Crockett |

| Geniocane | 1675 | 5 | Sycamore Crk | |

| Gueiquesale | 1674 | Sabinas & Rio Grande | ||

| Gueiquesale | 1674 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Gueiquesale | 1675 | Monclova & N Rio Grande | ||

| Gueiquesale | 1675 | N Monclova | ||

| Gueiquesale | 1706-1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Julime | 1656 | La Junta de los Rios | ||

| Julime | 1683-1684 | La Junta de los Rios | ||

| Julime | 1692 | La Junta de los Rios | ||

| Julime | 1706-1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Julime | 1716 | 5 | Colorado River (headwaters) | |

| Julime | 1716 | 9 | Colorado River | |

| Julime | 1726 | 3 | Nueva Vizcaya | |

| Julime | 1750 | Road to Rio Grande | ||

| Julime | 1770 | Rio Grande | ||

| Jumano | 1583 | Pecos River | ||

| Jumano | 1590 | Upton | ||

| Jumano | 1629 | ESE Santa Fe | ||

| Jumano | 1632 | Concho River area | ||

| Jumano | 1650 | Concho River area | ||

| Jumano | 1654 | Concho River area | ||

| Jumano | 1658 | Saltillo | ||

| Jumano | 1673 | Saltillo | ||

| Jumano | 1674-1675 | Monclova | ||

| Jumano | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Jumano | 1683-1684 | Concho River & La Junta | ||

| Jumano | 1686 | SW El Paso | ||

| Jumano | 1687 | some at La Junta | ||

| Jumano | 1688 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Jumano | 1689 | Pecos River | ||

| Jumano | 1689 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Jumano | 1690 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Jumano | 1691 | Guadalupe River (upper) | ||

| Jumano | 1692 | some at Parral | ||

| Jumano | 1693 | Guadalupe River area | ||

| Jumano | 1693 | some at Neches River | ||

| Jumano | 1706-1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Jumano | 1710 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Jumano | 1718 | South end S Plains | ||

| Jumano | 1734-1772 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Jumano | 1773 | E side Pecos River | ||

| Jumee | 1674 | N and S Rio Grande | ||

| Jumee | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Jumee | 1706 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Jumee | 1708 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Machome | 1686 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Machome | 1691 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Manos Prietas | 1674 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Manos Prietas | 1675 | N Rio Grande and Monclova | ||

| Manos Prietas | 1675 | Monclova area | ||

| Manos Prietas | 1678 | Monclova area | ||

| Manos Prietas | 1706 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Manos Prietas | 1716 | Colorado River | ||

| Mescal | 1686 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Mescal | 1689 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Mescale | 1690 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Mescale | 1691 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Mescale | 1693 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Mescale | 1699 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Mescale | 1700 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Mescale | 1701 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Mescale | 1706 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Mescale | 1708 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Mescale | 1716 | 5 | NNE Colorado River | |

| Mescale | 1716 | 5 | San Gabriel River area | |

| Mescale | 1716 | 5 | ||

| Mescale | 1700-1718 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Mescale | 1734 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Mescale | 1772 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Mesquite | 1675 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Mesquite | 1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Mesquite | 1708 | E Rio Grande near Guerrero | ||

| Mesquite | 1716 | Colorado River area | ||

| Mesquite | 1716 | San Jose and Solano | ||

| Mesquite | 1716 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Mesquite | 1716 | 9 | La Junta de los Rios | |

| Mesquite | 1726 | 8 | San Antonio | |

| Muruame | 1690 | San Marcus River | ||

| Muruame | 1700-1718 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Muruame | 1708 | E Rio Grande near Guerrero | ||

| Ocane | 1674 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Ocane | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Ocane | 1691 | Comanche Creek | ||

| Ocane | 1693 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Ocane | 1698 | Mission San Francisco Valadares | ||

| Ocane | 1703 | San Bernardo | ||

| Ocane | 1706 | San Bernardo | ||

| Ocane | 1708 | San Bernardo | ||

| Ocane | 1722 | San Bernardo | ||

| Ocane | 1726 | Coahuila | ||

| Ocane | 1734 | San Bernardo | ||

| Pachale | 1701 | Mission Dolores | ||

| Pachale | 1701 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Pachale | 1708 | San Bernardo | ||

| Pachale | 1726 | Nueva Vizcaya | ||

| Pachale | 1727 | Mission Dolores | ||

| Pacpul | 1691 | Comanche Creek | ||

| Pacpul | 1707 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Pacpul | 1726 | Coahuila | ||

| Pacuache | 1674-1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1686 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1690 | Frio River or Hondo River | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1691 | Frio River | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1693 | Comanche Creek | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1703 | San Bernardo | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1706 | San Bernardo | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1708 | San Bernardo | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1709 | 4 | Nueces River | |

| Pacuachiam | 1716 | Paso de Francia | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1718-1719 | Rio Grande and Leona Rivers | ||

| Pacuachiam | 1726 | Coahuila | ||

| Papanac | 1675 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Papanac | 1690 | Nueces River | ||

| Papanac | 1691 | Frio River | ||

| Papanac | 1700 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Papanac | 1706-1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Papanac | 1708 | N Rio Grande missions | ||

| Papanac | 1722 | San Bernardo | ||

| Papanac | 1734 | San Bernardo | ||

| Paponaca | 1703 | San Bernardo | ||

| Paragua | 1704-1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Paragua | 1707 | Between Frio and Leona Rivers | ||

| Paragua | 1708 | Eastern Rio Grande | ||

| Paragua | 1784 | San Antonio Valero | ||

| Pasti | 1707 | Nueces River | ||

| Pasti | 1708 | Eastern Rio Grande missions | ||

| Pataguaque | 1674-1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Pinanaca | 1674 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Pinanaca | 1675 | S and N Rio Grande | Maverick | |

| Puyua | 1707 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Saesse | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Saesse | 1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Saesse | 1708 | N Rio Grande missions | ||

| Sanaque | 1690 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Sanaque | 1708 | E Rio Grande | ||

| Sanyau | 1690 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Siano | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Teaname | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Teimamar | 1674-1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Teimamar | 1704-1707 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Teimamar | 1716 | Central Texas | ||

| Teimamar | 1718 | Presidio del Norte | ||

| Teneimamar | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Terocodame | 1675 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Terocodame | 1688 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Terocodame | 1700 | Rio Grande missions to west | ||

| Terocodame | 1706-1708 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Terocodame | 1720 | Coahuila | ||

| Terocodame | 1726 | Coahuila | ||

| Tilijae | 1675 | Edwards Plateau | ||

| Tilijae | 1690 | Mission La Caldera | ||

| Tilijae | 1706 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Tilijae | 1734 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Tilpayay | 1686 | Edwards Plateau | ||

| Tilpayay | 1690 | Medina River | ||

| Toboso | 1700-1708 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Xarame | 1701 | N Sabinas River | ||

| Xarame | 1701 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Xarame | 1708 | San Francisco Solano | ||

| Xarame | 1709 | 4 | Frio River | |

| Xarame | 1714 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Xarame | 1717 | Presidio del Norte | ||

| Xarame | 1718 | Presidio del Norte | ||

| Xarame | 1726 | Coahuila | ||

| Xarame | 1784 | San Antonio Valero | ||

| Xiabu | 1689 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Yorica | 1674 | N Rio Grande | ||

| Yorica | 1675 | Monclova area | ||

| Yorica | ca. 1686 | SW Edwards Plateau | ||

| Yorica | 1690 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Yorica | 1691 | S Rio Grande | ||

| Yorica | 1700 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Yorica | 1706 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Yorica | 1708 | San Juan Bautista | ||

| Yorica | 1710 | San Juan Bautista | ||

The records show other native groups who inhabited or used the micro-region, but their names do not appear in the registers of the Texas missions during the period of the late 1600s or later. These groups include: the Bagname, Bibit, Cacaxtle, Cibolo, [2] Gediondo, Machome, Pacpul, Pinanaca, and Teaname. Some may have become incorporated into other groups who had higher populations and enjoyed more influence. Others may have had too few members to survive ethnically and culturally.

In the early decades of the eighteenth century some groups appear to have shifted their activities north of the Rio Grande (i.e., Ervipiame, Mescal, Mesquite, Teimamar, and Xarame), while others appear to have remained in the area of the Rio Grande (i.e., Ape, Gueiquesale, Jumee, Ocane, Pachale, Pacuachiam, Saesse, and Yorica). This shift was undoubtedly a result of the move of Spanish activities to the area of San Antonio and the Gulf Coast. As discussed above, the Rio Grande settlements lost their centrality with the establishment of the missions and presidio in San Antonio. Fortunately, the Sacramental Records of the various Texas missions provide some continuity to the movements and fate of some native groups (see Appendix 2). A comprehensive review of all the Sacramental Records may provide further clues about the processes of amalgamation between groups.

During the initial centuries discussed here, the Jumano stand out as the group who appear to have had a more extensive geographic range of activities (see Kenmotsu 2001). If we include the encounters recorded for the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (see Table 2) that range is unparalleled. However, this impression may result from the lack of recorded information about other groups for the same period of time, or because the particular mode of life of the Jumano was conducive to plural encounters and unusual visibility. Within the area of northeastern Coahuila and Texas, the Cibolo and the Ervipiame (see Table 2) appear to be close seconds in terms of the range of their activities and visibility.

The Jumano also exemplify another aspect of Native American history. By the early 1600s, certain areas, such as the Bolson de Mapimi, located southwest of the Amistad NRA, had begun to "serve as a convenient refuge area[s] for disaffected natives" (Griffen 1969:1). Some of those groups were native to the area; others came from long distances. As these events took place, resident native groups in the area found they had to seek an accommodation with the disaffected groups who had pushed in or find themselves at odds with the newcomers. In some cases, the native groups who had occupied the landscape prior to these types of shifts were decimated by wars (cf. the Masame [Kenmotsu 1994:338]). In other cases, native groups determined that wars were not the solution and eventually joined larger groups as a means of survival. The latter solution was chosen by the Jumano. At first, the Jumano fought the Apache, but later became their allies. Finally, in the mid-eighteenth century, the Jumano are listed as "Apaches Jumanes" indicating that they had 'become' Apache (Kenmotsu 1994:328).

Individual Native Groups

1535-1750

In this section, we summarize cultural information on individual native groups who appear in the historical records for the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and were connected with the Amistad NRA and our micro-region. Most of the earliest groups disappeared from the ethnohistoric record long before the Anglo American settlement of the Lower Pecos region where the Amistad NRA is situated. Often, their names were listed in Spanish documents as a phonetic rendition of their actual name or the meaning of their native name was translated into Spanish. For each native group, we offer a list of the phonetic variations of the same name. [3] The summary also includes the principal locations where each group was reported within the modern territory of Texas and the group's known associations. The listing of a group's allies or enemies is restricted to those groups who were reported north of the Rio Grande or immediately south of it (see Table 2). The Apache, senso latu, are included in this summary even though the temporal span of the Apache presence in Texas extends well beyond 1750. Similarly, the Yorica and Ervipiame presence in Texas extended well after 1750. The cultural summary for the Apache and Ervipiame presented here includes only material gathered until 1750; their activities after 1750 are found later in this chapter. The summary for the other native groups includes all the cultural material that could be gathered by the authors for each group. Many of the details for the dates reported below are found in date order in Appendix 4. Data are included from both the macro- and micro-regions.

Apache

(1680s through ca. 1750)

(Wade 1998:418-423)

Early Names Used for Apache Groups:

1683-84: Apache

1691: Apache, Sadammo, Caaucozi, Maní

1710: Jila, Fahanos, Necayees (AGI 1710)

1732: Apaches, Ypandi, Yxandi, and Chenti

1743: Ypandi; alias Pelones

1743: Ypandes, Apaches, and Pelones or in the language of the same northern Indians [sic] Azain, Duttain, and Negain (AGN 1723)

1745: Ypandi, Natagé

1749: Ypandi, Natagé

Principal Area in Texas:

1683-84: north of the Pecos River (north of Crockett Co.)

1690s: traveled south to the Colorado River but were located north and west of that river

1691: west of the Tejas (Caddo)

1702-1704: six baptismal records at Mission Solano

1704: request peace at El Paso (AHP 1704A)

1712: small bands present in La Junta de los Rios (AGI 1716)

1717: Apache attack west of the Colorado River

1719: Gov. Olivares places them from Missouri to Red rivers and west to New Mexico (BA 1719)

1722-1723: several attacks near San Antonio and on the road between this town and the presidio on the Rio Grande

1723: five Apache groups near the San Saba

1726: Apache attack Sana and Pacuache on the Nueces River

1729: Apache bordered the lands of the Mansos near El Paso (AHP 1649D)

1732: Spanish attack very large Apache rancherias north of San Saba

1736: Apache attack Native Americans at mission in San Antonio (AGN 1736)

1737: Attack the Rio Grande mission to steal horses (PI. v. 32)

1739: Spanish attack Apache possibly near San Saba

1741: Ypandi wish to settle on the Guadalupe River

1743: Comanche said to displace Ypandi (alias Pelones) from their lands

1743: Apache at war on the Rio Grande; attack others on the road between San Antonio and the Rio Grande

1743: Pelones said to be living the farthest from Béjar while the Ypandi were the closest to the Presidio (AGN 1743)

1745: Spanish attack Ypandi and Natagé 80 leagues north of San Saba

1746: Ypandi ask for missions

1748-49: Spanish attack Apache hunting on the Guadalupe River; Spanish make two other punitive expeditions to other locations

1749: Ypandi and Natagé establish peace agreement with Spanish

1750: Apache "Chief' Pastellano requests mission at San Juan Bautista on the Rio Grande

Principal Group Associations:

1688: Enemies of the Ervipiame, Jumano, the Tejas and their allies

1691: Friends with the Salinero; enemies of the Caynaaya, Choma and Cibola

1716: Request peace with the people of La Junta and the Spanish

1723: Trade horses to the Caddo in East Texas

1726: Enemies of the Sana and Pacuache

1732: Friends of the Jumano

1743: Enemies of the Comanche

Cultural Information: The cultural information available for the Apache during the early part of their presence in modern Texas is very scant and some of what was recorded by the Spanish reflected their observations on the various Apache divisions in other areas of New Spain. In 1542, while in the Texas Panhandle, Coronado encountered groups of individuals hunting buffalo and using travois pulled by dogs to transport their belongings. Most authors agree that these individuals, whom Coronado called Querechos, were Apache. Several of the subsequent encounters between the Spanish and the Apache, within the territory of Texas, took the form of hit-and-run attacks by the Apache and provided little recorded information about their cultural behavior. Nevertheless, from the start the Spanish military commented extensively on the excellent horsemanship of the Apache and on the courage displayed by their warriors in battle.