|

AMISTAD

Cultural Resources Study |

|

THE STUDY

GOAL

This Cultural Resources Study is designed to identify the most significant and imperiled cultural sites in the three major river valleys and intervening side canyons on the United States side of Amistad International Reservoir. It establishes site locations, determines their integrity and condition, describes some of their characteristics, and evaluates their significance in relation to possible acquisition.

|

| Rio Grande River, Panther Cave. Source: David Muench |

BACKGROUND

Amistad Dam / Reservoir

In 1944, the United States International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) and the government of Mexico signed a joint water treaty (see appendix) that affected the Rio Grande from El Paso to Brownsville, Texas. The treaty proposed to construct, operate, and maintain three international hydroelectric and flood control dams along the Texas/Mexico border. Two of these reservoirs have been built: Falcon Reservoir near Eagle Pass, Texas; and the 6-mile-long (9.6-km-long) Amistad Dam northwest of Del Rio, which was completed in 1969. The third reservoir is yet to be built.

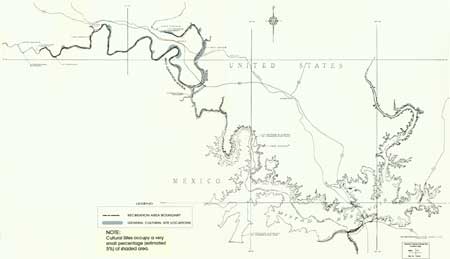

At a normal pool level (1,117.0 feet, or 340m, above mean sea level) impounded waters behind the dam create a 64,860-acre reservoir that extends in the United States about 25 miles (40km) up the Devils River valley; 14 miles (22km) up the Pecos River Valley; and 73 miles (118km) up the Rio Grande Valley. The reservoir has an estimated shoreline of about 850 miles (1,368km), of which about 540 miles (869km) are in the United States. The International Boundary and Water Commission acquired the title to the land or flowage easements equal to the maximum flood pool for the lake (1,144.3 feet, or 349m, above mean sea level).

National Park Service Responsibility

The National Park Service operated Amistad Recreation Area primarily as a water oriented recreation unit of the National Park System under a cooperative agreement (appended) with the United States Section of the International Boundary and Water Commission from November 11, 1965, to November 27, 1990. Under this agreement, the National Park Service had the general responsibility for:

"Promulgating and enforcing such rules and regulations as necessary or desirable for the conservation of any historic or archeological remains, and control of all archeological excavation and historical or archeological research, or as may be needed for recreational use and enjoyment of the area." (Article II, No. 5)

Public Law 101-628 (November 28, 1990), passed by the 101st Congress of the United States, provided the recreation area with its first enabling legislation (see appendix), defining the role of the National Park Service at Amistad Reservoir, and mandating National Park Service protection and management of the area's cultural, natural, scenic, recreational, and scientific values. This legislation also authorized minor boundary revisions and acquisition of lands and interests in lands up to a total Federal ownership of 58,500 acres. In addition, it changed the area's name from "Amistad Recreation Area" to "Amistad National Recreation Area."

According to the 1990 legislation, the NRA consists of Federal lands, waters, and interests within an authorized boundary, which is defined on a July 1969 boundary map (appended). This authorized boundary comprises 62,452 acres; Federal ownership within this boundary comprises 57,292 acres. In general, the boundary of the Federally owned lands (57,292 acres) can be conceived as a sinuous, imaginary line extending some 540 miles (869km) along the shoreline (the 1,144.3 contour) on the U.S. side of the lake (the total shoreline is estimated at 850 miles, or 1,368km). In effect, Federal ownership extends roughly 30 feet (9m) above the normal pool level of the lake. In some areas, this means that the line between Federal and private lands is located 30 feet (9m) up a 200-foot (61 m) vertical cliff face. This situation meets the basic needs of the International Boundary and Water Commission to manage the lake; however, it does not meet the mandate of the National Park Service to manage resources of national and international significance adjacent to Federally owned lands. The 1990 legislation authorized Federal acquisition of an additional 1,200 acres of land or interests in land.

THE SITE SURVEY

The vast majority of previously known cultural sites not inundated in 1967 by the Amistad Reservoir are located along a 10-mile stretch of the lower Pecos River and a 20- to 25-mile (32-40km) section of the upper Rio Grande. The time and funding constraints of the present Cultural Resources Study would not allow for a survey of the entire 540-mile (869km) shoreline of the lake, so a selected sampling of cliff and canyon walls that are known to contain the vast majority of all previously documented cultural sites was targeted. Fieldwork was purposely limited to locales situated between the national recreation area's current boundary (1,144.3 feet, or 343km, above mean sea level) and the canyon rim. Only a few upland areas with known historical sites were surveyed.

The level of investigation for the fieldwork was limited to an intensive, reconnaissance-level, pedestrian survey (as defined in NPS-28, it was conducted by walking, and looking for more than big caves) that did not involve subsurface testing, excavations, or the collection of any types of artifacts or samples for later analysis. Nearly all survey areas were reached by boat. Such reconnaissance-level documentation produces only the most basic information about a site; other National Park Service projects, such as the National Archeological Survey Initiative (NASI), acquire data sufficient for determinations of eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places, and meet the standards of the National Park Service's Cultural Sites Inventory (CSI).

The present Cultural Resources Study project has relied heavily on data produced by previous National Park Service archeological surveys and academic research accumulated over the last 60 years from other field studies in the Lower Pecos River region of southwest Texas and northern Coahuila, Mexico. Prior to the flooding of portions of the Pecos, Devils, and Rio Grande valleys, the National Park Service and the University of Texas at Austin conducted nearly 10 years of cultural resources inventory work that collectively documented more than 300 prehistoric archeological sites, including the excavation of 22 major sites, which produced a museum collection estimated to contain in excess of 1 million objects.

But the cornerstone of the present Cultural Resources Study is the data compiled during the National Archeological Survey Initiative Re-inventory project conducted by the National Park Service at Amistad National Recreation Area between December 1991 and April 1993 in response to the passage of Public Law 101-628. The survey re-investigated about 100 of the most significant sites around the lake shore, and identified more than 250 new sites overlooked during the pre-inundation research of the 1960s. Approximately 12 weeks of field-survey work were used to supplement existing information (derived principally from the NASI data) for selected geographic areas adjacent to current park boundaries for which little or no information previously existed.

|

| (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

THE SITES

Priorities

The following 298 archeological and historical sites are identified by this project for possible inclusion within the boundaries of Amistad National Recreation Area.

High-priority: 18, 19, 24, 26, 29, 30, 31, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 50, 51, 52, 54, 55, 56, 57, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70, 78, 79, 80, 82, 87, 88, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 97, 98, 101, 103, 104, 105, 106, 109, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 128, 129, 131, 132, 134, 136, 137, 138, 149, 151, 152, 153, 155, 156, 157, 158, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167,177, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 189, 191, 193, 210, 218, 224, 225, 227, 234, 237, 238, 239, 240, 286, 314, 323, 324, 325, 344, 348, 419, 422, 447, 448, 573, 586, 595, 643, 644, 648, 650, 656, 673, 685, 729, 741, 753, 760, 765, 780, 786, 794, 796, 797, 820, 839, 850, 907, 911, 912, 914, 951, 952, 953, 954, 1190, 1201, 1204, 1205, 1206, 1207, 1215, 1219, 1280, 1310, 1312, 1362, 1372, 1373, 1389, 1392, 1398, 1399, 1404, 1422, 1424, 1428, 1432, 1435, 1438, 1439, 1440, 1441, 1456, 1457, 1459, 1462, 1465, 1466, 1468, 1470, 1472, 1476, 1477, 1479, 1484, 1487, 1488, 1495, 1501, 1502, 1505, 1511, 1519, 1524, 1534, 1541, 1542, 1547, 1550, 1551, 1553, 1560, 1561, 1565, 1570, 1573, 1575. (Total=219)

Lower-priority: 32, 71, 86, 96, 117, 118, 127, 133, 148, 168, 173, 174, 175, 176, 204, 205, 206, 322, 345, 346, 421, 454, 628, 647, 740, 788, 816, 817, 819, 821, 837, 838, 1202, 1277, 1288, 1311, 1351, 1352, 1353, 1355, 1367, 1368, 1379, 1382, 1384, 1385, 1386, 1387, 1388, 1391, 1400, 1401, 1406, 1414, 1416, 1420, 1429, 1430, 1446, 1460, 1461, 1474, 1480, 1481, 1492, 1507, 1514, 1517, 1518, 1520, 1536, 1537, 1545, 1552, 1558, 1563, 1571, 1572, 1577. (Total=79)

| Total High-priority Sites: | 219 |

| Lower-priority Sites: | 79 |

| TOTAL: | 298 |

A large number of these significant sites are located in four archeological districts listed on the National Register of Historic Places—the Lower Pecos, Seminole Canyon, Rattlesnake Canyon, and Mile Canyon districts.

Classification

There are a variety of methods and classificatory systems used by archeologists to group artifacts, or to describe the cultural sites from which materials are collected or excavated. For the purposes of this report, site classifications are presented at a very general level, rather than delving into the more complex typologies and terms used commonly by researchers in the field. Further, the typologies used here (function and time) are intended to apply only to the Amistad Reservoir region.

In general, the specific typology chosen for an archeological report is dictated by the scope of the research design and amount of data generated during the project. For example, the simplest of reports often groups a large data base of cultural sites on the basis of the physical or topographic landforms on which they occur, such as terrace, rockshelter, or upland. However, such typologies have very limited interpretive applications, and do little to explain the past socioeconomic activities that produced the sites themselves. At the other end of the spectrum are complex typologies that utilize the type/variety system to extremes, often making such reports incomprehensible to general or non-academic readers.

More common is a typology that groups cultural sites by functional categories and by time periods of original deposition. Past site function(s) can be inferred collectively from the artifacts or feature(s) at the sites. The absolute dating for a specific cultural time period is determined by radiocarbon dating methods or by known temporal markers (artifacts or pictographs) within an established chronology. As a general rule, any of the prehistoric functional site types can occur during any of the cultural time periods.

All cultural sites investigated and evaluated by this project were assigned to the site types and cultural time periods listed below. Within each category, sites were then rank-ordered in terms of overall desirability. Where feasible, the most desirable sites within each category have been identified for acquisition, with emphasis placed on getting the widest possible range of sites.

Functional Typologies: There are essentially only two basic site types for the region throughout all cultural periods of American Indian prehistory. At the general level, occupational sites and ceremonial sites are differentiated by the type/variety of the archeological features and artifacts that may be (or may not be) present at particular cultural sites. Different feature (or artifact) types infer different site functions. For example, lithic debris on the ground surface infers that someone used the area to make tools used in subsistence activities; or prehistoric pictographs on a rockshelter wall infer that the area was used for ceremonial purposes rather than for ordinary subsistence activities; or prehistoric pictographs on a rockshelter wall infer that the area was used for ceremonial purposes rather than for ordinary occupational or subsistence activities. Some archeological features are usually identified through excavation (for example, burials, perishable deposits, or bison jump/drive sites); other feature types are discernible by simple observation (for example, pictographs or burned rock middens). Any cultural site can function differently over time, so that a particular site classification (occupational or ceremonial) applies only to a specific cultural period of time (with finite limits). The vast majority of sites contain more than one of these types and could be classified in either category.

Occupational Sites:

Lithic scatter (chipping debris from tool manufacture)

Quarry (locale where chert deposits were exploited)

Burned rock scatter (scattered remains from campfires)

Burned rock midden (concentration of burned rock)

Midden (occupational remains without major concentrations of burned rocks)

Perishable deposits (preserved plant materials)

Bison jump/drives (deposit of bison bones below a cliff)Ceremonial Sites:

Pictograph (painted image on rockshelter walls)

Petroglyph (carved or incised image on walls or in open-air locations)

Burials (purposely placed human internments)

Cultural Time Periods: Sites are temporally classified as either prehistoric (10,000 B.C.-plus to A.D. 1590) or historic (after A.D. 1590). The past 10,000 years of human activities in the region are generally divided into five major prehistoric analytical units (periods), each of which is further subdivided into a number of minor phases. Each major prehistoric period was dominated by a particular type of subsistence pattern, diagnostic artifacts, mortuary pattern, and rock art style. Historic sites are classified by time period—that is, on the basis of the major historical (European) periods, and eras (shorter periods dominated by a single political, social, ethnic, or economic interest). Please note that the cultural chronology listed below applies only to the Amistad National Recreation Area region.

| Prehistoric | |

| Paleolndian | (10,000 B.C. to 7,000 B.C.) |

| Early Archaic | (7,000 B.C. to 4,500 B.C.) |

| Middle Archaic | (4,500 B.C. to 1,000 B.C.) |

| Late Archaic | (1,000 B.C. to A.D. 600) |

| Late Prehistoric | (A.D. 600 to A.D. 1590) |

Historic | |

|

American Indian Period Spanish Colonial Period, 1590-1821 Mexican Period, 1831-1836 Texas Republic Period, 1836-1845 Texas Statehood (pre-Civil War), 1845-1861 Civil War Period, 1861-1865 Texas Statehood (post-Civil War), 1865-1880 Railroad Era (Southern Pacific RR), 1880-World War II Ranching Era, 1880-World War II | |

Selection criteria

For the present Cultural Resources Study, it was understood that all known sites adjacent to the 540-mile reservoir shoreline could not be acquired by the National Park Service without exceeding the authorized acreage limitation established by Public Law 101-628. Therefore, an evaluative method had to be devised that would target the most significant sites within each of the major site types present in the region. Evaluation also included management feasibility factors such as access, ability of the NPS to protect a given site, interpretive potential, and development costs.

There are all types of standards upon which to base evaluations of archeological sites, such as National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) standards, National Park Service standards, and the Texas Antiquities Code. Each of these established systems uses slightly different criteria to determine the "significance" of a cultural property. The criteria used by this project represent a combination of established standards combined with administrative issues relevant to the day-to-day management and protection of a particular site.

A total of about 400 prehistoric and historic sites were ultimately selected for evaluation from an original pool of nearly 600-700 sites. The site pool was narrowed down using information from the NASI Project and archival information on record with the State of Texas. Archeological site data forms were obtained and reviewed for roughly 500 sites. For each site evaluated, a series of 15 questions were asked, with answers recorded on a Management Evaluation Form. The range of questions represents an attempt to balance the two major issues of (1) the significance of the sites (the scientific significance as defined by NRHP and NPS-28); and (2) the overall feasibility of National Park Service administration of the site (considering size, configuration, ownership, costs, and other management concerns). A numeric value of 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest) was assigned for each question; sites could then be numerically rank-ordered. This system, which required a number of subjective calls by the evaluators, quickly identified the "best/worst" sites in the pool, but was not of much help in evaluating sites between the two extremes. For sites ranked in the mid-range, evaluators reviewed the files for each one, in an effort to decide the overall desirability of recommending it for possible acquisition. The Management Evaluation process should be viewed as a measure rather than as an absolute tool with which to gauge relative site significance.

The following 15 criteria were used:

1. Condition of the archeological deposits: This question sought to determine present site conditions. A site with intact archeological deposits greater than 90 percent received the highest rating; deposits of less than 10 percent were rated lowest. Whether the site was a single-component (one-time-period) or multiple-component (multiple-time-period) was also a factor. Determining the archeological potential of a site is rather subjective; it requires a detailed knowledge derived from fieldwork at many sites.

2. Condition of archeological features at the site: Archeological features are generally considered to be those archeological features at a cultural site that are not taken back to the laboratory or museum, such as prehistoric paintings (pictographs) on walls, and grinding holes (to grind seeds into meal) made into boulders within rockshelters. Subsistence-related features include grinding facets, mortar holes, and incised grooves. Ceremonial or religious activities can generally be inferred from the presence of pictographs, petroglyphs (designs produced by carving, rather than painting), and cupules (small holes pecked into a rock for ceremonial purposes, rather than normal food preparation). The condition of such features—ranging from pristine to badly deteriorated—makes a difference when evaluating the potential for research to provide scientific information.

3. Condition of pictographs: This question obviously applied only to sites with pictographs, but allowed for a general assessment of the quality, condition, and complexity of the pictographs in terms of scientific value. Many of the region's pictograph sites have suffered from graffiti and vandalism, in addition to the natural processes of deterioration.

4. Number of archeological features: This question sought to broadly define the complexity or number of prehistoric activities that could be inferred from the features still present at the site. Generally, the more complex a site is, the greater the research potential is for providing new or significant data about how the site may have been used.

5. Research or special-studies potential: Not all archeological sites were created equal; therefore, some sites are much more important for research than for public interpretation. Sites were evaluated according to their archeological potential for providing significant data that can address current research questions.

6. Level of previous investigations: The amount or level of previous archeological research (or vandalism) has a direct bearing on the future potential of a site for providing significant new information. A small site that has been partially vandalized by relic hunters received a higher rating than a large site that has been thoroughly excavated. Sites that have produced Federally-owned artifact collections (from previous NPS surveys, excavations, and conservation projects) were rated higher than sites where no Federal collections have been made.

7. National Register of Historic Places status: Sites already listed as part of an existing National Register District, or in proximity to an existing National Register District, received the highest rating; sites that had previously been determined ineligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places received the lowest rating.

8. Location of site relative to standard park ranger patrols: This question sought some basic information about the national recreation area's ability to manage the site, given the size of the three NRA districts. In the Pecos River District, for example, there are roughly 75 miles (120km) of shoreline, some of which are nearly inaccessible to current ranger patrols. Sites located within the range of daily patrols were rated highest; sites requiring a special trip were rated lowest. If the site could be acquired as part of a larger geographic group or cluster of sites (versus an isolated acquisition), it was rated higher than isolated sites.

9. Time required For basic site monitoring during patrol: This question sought to establish the amount of time required to climb up to the site, examine it for vandalism or natural disturbances, and return to the boat. Sites requiring fewer than 10 minutes received the highest ratings; sites requiring more than 30 minutes received the lowest. Sites currently bisected by the 1,144.3-foot contour line (349m) were rated high. The farther away from lands currently managed by the NPS, the lower the rating.

10. Initial National Park Service investment for minimal site protection: This question sought to establish a basic dollar figure that would be needed to protect a site. Sites rated highest would need only boundary markers; those rated lowest would require costly electronic sensors as the only viable option for monitoring.

11. Potential for public interpretation: Not all sites lend themselves equally to public interpretation. An archeological site may have tremendous research potential but not be of much interest to the general public. Most park visitors seem to be more impressed by a small rockshelter with pictographs than by a large rockshelter that only has buried deposits.

12. Estimated cost for development as an interpretive site: Some archeological sites require a minimum investment for interpretive developments, while other sites are literally cost-prohibitive. Short-term costs to consider include signage, fencing, and trail construction. Long-term costs consist of security; control of public access; and conservation, stabilization, and research project costs.

13. Relative distance of site from recreational campsite: The closer a cultural site is to a designated camping area, the greater the likelihood that the site will be vandalized. This question sought to identify clusters of sites near campsites that could pose a future management problem if not addressed early in the planning process.

14. Visibility of site: The more visible on archeological site is, the greater the chances are that it will be vandalized. Sites that are hidden by trees or dense vegetation are less likely to be vandalized than those in the open. In recent years, the use of landscaping (with native plants) to hide highly visible sites has become an accepted preservation technique.

15. Accessibility of the site: Public access to many sites selected for acquisition would be by boat. Less than 5 percent of the targeted sites are located on adjacent uplands that would require the acquisition of overland access. The more difficult the climb to a rockshelter, the less likely it is that it will be disturbed by casual park visitors. Sites with easy access are most often frequented by ordinary or physically impaired park visitors. Sites that are difficult to access or are off the beaten trail are generally the preferred target for relic hunters.

Evaluation

Revision, where necessary, of the authorized (62,452-acre) boundary and acquisition of some interest in these sites are the only feasible means of protecting pictographic rock art, rockshelters, and other prehistoric sites that are (1) in the immediate vicinity of the Federally owned lands of Amistad National Recreation Area and (2) have significance equal to or greater than the sites known to exist within the NRA.

Amistad National Recreation Area is divided into three administrative districts—the Pecos River District, the Rough Canyon District, and the Diablo East District.

Adjacent to the Pecos River District, there are 249 sites recommended for acquisition. Nearly all the sites are located in the cliff walls adjacent to the river, or in intervening side canyons. The most practical situation would be for the National Park Service to acquire the land from the lake level to the top of the cliff walls along stretches of the Pecos and Rio Grande where multiple sites exist.

There are 47 sites proximate to the Rough Canyon District that are recommended for acquisition. The primary reason for the low number of sites in comparison to the Pecos River District is that much of the topography adjacent to the Devils River does not lend itself to rockshelter formation. Most of the significant sites are located up side canyons at some distance from current Federal lands. Acquisition of these sites would also require the purchase of access to enable the National Park Service to effectively manage the sites. The most significant cluster of archeological sites is in the area commonly called Indian Cliffs. The National Park Service has been approached by the landowner in this area, and donation, rather than purchase, of the sites is now a possibility.

There are no sites in the vicinity of the Diablo East District recommended for acquisition. Generally, this district consists of low, rolling hills without any large or extensive stretches of cliff walls. There are no deep canyons or major intervening side canyons.

Most of the lands adjacent to park boundaries have been used for ranching activities for the past 100 years; however, during the post 25 years since the lake was built, traditional land use patterns have begun to change. Several large ranches have been sold or subdivided, with acreage being sold on a lot basis for private housing. There are now at least half a dozen subdivisions scattered around Lake Amistad, concentrated mostly on the Devils River. However, most of the pristine wilderness areas along stretches of the upper Rio Grande and lower Pecos River still remain virtually unimpaired by private development.

Private development of lands adjacent to the lake is not compatible with the long-term preservation of the many archeological resources at Lake Amistad. As more people begin to live near the lake, there will be a concomitant increase in illegal activities such as pot-hunting, theft of artifacts, and vandalizing of the pictograph sites.

All land adjacent to the lake is privately owned except for a 5,000-acre parcel on the Rio Grande managed by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Division as Seminole Canyon State Historical Park. With so much private land adjacent to the lake, future land use is unpredictable. Potential future land-use changes in the larger area surrounding the NRA include two toxic waste dumps and several more subdivisions.

If small areas containing significant cultural sites were acquired by the National Park Service, they would be managed in non-consumptive ways, primarily for archeological resource preservation, research, and interpretation.

There is a good chance that two important tracts of land may be donated, rather than sold, to the National Park Service by landowners in the Pecos River District. The Rock Art Foundation of San Antonio, Texas, has already entered into serious discussions with the Southwest Regional Office of the National Park Service concerning the donation of approximately 400 acres of land that include several major archeological sites. Texas Tech University has also raised the possibility of donating the Rattlesnake Canyon Archeological District (92.3 acres) to the National Park Service if legal issues concerning the transfer of land from a State entity to a Federal agency can be resolved. The Rattlesnake Canyon site is considered by most to be the second most important remaining pictograph site in the region. The most significant is Panther Cave, which is jointly managed by the National Park Service and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Division.

All of the possible acquisitions listed in this report would be administratively feasible to manage in terms of access, protection, and operational and development costs. Additional park staff would be required for law enforcement, interpretation, and maintenance. Exact numbers would be dependent upon the total number of sites acquired by the National Park Service, with estimates currently ranging between three and five fulltime employees.

THE NEXT STEP

Based on continuing land status research, the National Park Service will prepare a Land Protection Plan. This plan will (1) recommend minor boundary revisions as authorized in Public Law 101-628; (2) identify lands or interests in land required to meet the Congressional mandate for Amistad National Recreation Area; and (3) develop priorities for acquisition. Landowners and other interested publics will be involved in the preparation of the Land Protection Plan.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

amis/crs/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 26-Mar-2007