|

Andersonville National Historic Site Georgia |

|

NPS photo | |

Courage and Sacrifice

Imagine yourself as a prisoner of war (POW) struggling to survive in a disease-ridden prison, sometimes in aching isolation, sometimes in filthy, overcrowded conditions. Imagine the day-to-day uncertainty when all you can think about is food, water, freedom, and death. What was it like to be, as one soldier wrote, "dead and yet, breathing"?

Would freedom ever come? How? When? Could you escape? Should you try? Questions like these tormented POWs. For some, freedom came in a matter of days; others waited torturous years. Too many found freedom only in death.

Andersonville prisoner George Tibbles, 4th Iowa Infantry, recalled, "No one can imagine the agony of continued hunger unless he has experienced it. I have felt it, witnessed it, yet I cannot find the language to adequately describe it." POW experiences connect soldiers from one generation to the next. When William Fornes, held as a POW in Korea, visited Andersonville he said, "A feeling came over me that I had something in common with these people, and I feel that way about all wars."

Since the American Revolution our soldiers have marched off to war, defending our country, families, and liberties. Some have given their lives. Some have been captured and held as POWs, subjected to torture, starvation, inadequate medical care, and unspeakable conditions. Some have returned home but have been forever changed.

I had an undying faith that my country was not going to forget me. No matter how long I stayed there, no matter even if I died there, my country was not going to forget me.

—Col. Tom McNish, USAF, POW Vietnam 6½ yrs.

Civil War Prisons: A Cruel Legacy

In 1901 and 1911 Emogene Marshall traveled from Ohio to visit the grave of her brother, Edwin Niver, buried here in grave 2,183. In the decades following the Civil War, Americans were haunted by the deaths of their loved ones in military prisons. Although Andersonville is now the most infamous Civil War prison, some 150 others were set up across the country. In 1863 the Union and Confederate governments adopted laws of war to protect prisoners, yet some 56,000 soldiers died in captivity. How and why did this happen?

When the Civil War started, neither side was prepared to hold thousands of enemy prisoners. Although no formal exchange system existed early in the war, both armies paroled prisoners to lessen the burden of providing for captives. Prisoners of war were conditionally released, promising not to return to battle until officially exchanged.

A formal exchange system adopted in 1862 failed when the Confederacy refused to exchange or parole captured black US soldiers. In the South, captured Union soldiers were first housed in old warehouses and barns around Richmond, Virginia. As the number of prisoners increased, prisons were hastily erected in Florence, South Carolina; Millen and Andersonville, Georgia; and other locations. In the North, Federal training camps were converted into prisons at Camp Douglas, Illinois; Camp Chase, Ohio; and Elmira, New York. Other Confederate prisoners were held at Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, and other coastal fortifications.

Confined soldiers suffered terribly from overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate food. Mismanagement by war-weary governments worsened matters. Most prisoners died from disease, starvation, or exposure. The end of the war saved hundreds of prisoners from an untimely death, but for many the war's end came too late. For the men who survived, the memory of the atrocities they witnessed was the cruelest legacy of all.

Prisoner of War Camps — North and South

Civil War Prisons' Death Toll

Whether held in the North or South, a prisoner of war was more likely to

die than a soldier in combat. Prisons were overcrowded, short on food,

medical supplies, shelter, and clothing, while disease and death ran

rampant. How many prisoners died is not known. Surviving records suggest

some 30,000, or 15 percent of Union prisoners, and about 26,000, or 12

percent of Confederate prisoners died.

Andersonville National Historic Site is the only national park serving as a memorial to all American prisoners of war. Once filled with desolation, despair, and death, Andersonville now offers a place for remembrance and reflection. Here we remember POWs and honor their courage, service, and sacrifice. Walk the grounds of Andersonville—the Prison Site, where nearly 13,000 Civil War soldiers died in 14 months, mostly from disease and starvation; the National Prisoner of War Museum, dedicated to American soldiers who suffered captivity in all wars; and Andersonville National Cemetery, a final resting place for our veterans.

The camp was covered with vermin all over. You could not sit down anywhere. You might go and pick the lice all off of you, and sit down for a half a moment and get up and you would be covered with them. In between these two hills it was very swampy, all black mud, and where the filth was emptied it was all alive; there was a regular buzz there all the time, and it was covered with large white maggots.

—Sgt. Samuel Corthell, Co. C, 4th Massachusetts Cavalry

Black Soldiers: Captives for Freedom

On January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation allowing African Americans, enslaved and free, to enlist in the Union army. The North demanded all captured soldiers be exchanged equally, but the South refused to exchange black prisoners. Some Confederate officers ordered African Americans killed, not captured. Some former slaves were returned to their owners, some were sold, and others were forced to work for the Confederacy.

Records show over 100 African American soldiers were imprisoned at Andersonville. Black prisoners set up their own area near the south gate, received no medical treatment, and were forced to work the burial detail and other hard labor. They were discriminated against by their captors and fellow prisoners, who believed they were the reason the Union refused to make prisoner exchanges.

At the trial of Captain Wirz black prisoners testified they were treated "just the same as any of the rest." However, punishment was severe. Pvt. William C. Jennings, 8th US Colored Troops, received 30 lashes for not going to work and was put in the stocks, while Isaac Hawkins of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry received 250 of 500 lashes. Records show 33 African Americans died at Andersonville and were buried side-by-side with fellow prisoners.

Capt. Henry Wirz

Swiss-born Henry Wirz enlisted in the Confederate army early in the war and was soon detailed to work in the Richmond, Virginia, prison network. He worked at prisons in Virginia and Alabama before taking command of Andersonville in March 1864. At war's end, nearly 1,000 individuals were tried for violations of the laws of war. Captain Wirz remains the most famous of the officers executed for war crimes.

After the War

What happened to Andersonville prisoners? Hundreds died on their way home when the steamboat Sultana exploded and sank near Memphis, Tennessee, April 27, 1865. Many others died of diseases contracted during their imprisonment.

In 1890 the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a Union veterans organization, purchased the site. The Woman's Relief Corps (WRC) of the GAR took charge of the property, hoping to create a memorial park. In 1910 the WRC donated the prison site to the people of the United States. It was administered by the War Department and the Department of the Army until Congress designated it a national historic site in October 1970.

Dorence Atwater

Nineteen-year-old Dorence Atwater, 2nd New York Cavalry, was captured in July 1863. He spent eight months in Richmond, Virginia, prisons before arriving at Andersonville. In June 1864 he was detailed to work in the hospital where he recorded the names and grave locations of the deceased. He secretly copied this list and smuggled it out when he was released.

After the war he asked the War Department to publish the list, but they refused. He met Clara Barton, a battlefield nurse, who was looking for missing soldiers. She was eager to help. Barton accompanied Dorence and the US Army Quartermaster expedition to Andersonville to mark the graves of the dead. Atwater's death register, published in 1866, enabled many families to locate their loved ones. Thanks to his work, over 95 percent of the graves were identified.

Where We Held Each Other Prisoner

(click for larger maps) |

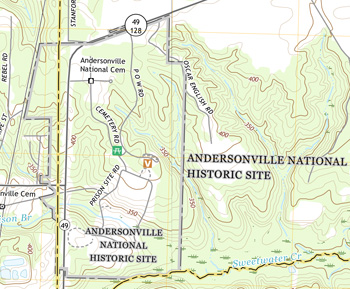

National Prisoner of War Museum, Prison Site, Andersonville National Cemetery

Established in 1970, Andersonville National Historic Site has three main features: the National Prisoner of War Museum, which also serves as a visitor center; the Prison Site; and Andersonville National Cemetery.

Start your visit at the POW Museum. It describes both the Civil War prison camp and the hardships, experiences, and sacrifices of American POWs throughout history.

Prison Site Hastily built relieve crowding in Richmond prisons and to relocate Union prisoners away from the battlefront, Camp Sumter military prison, commonly known as Andersonville, was an unfinished, undersupplied prison pen when the first prisoners arrived in February 1864. Intended to hold 10,000 men, the 16½-acre pen had a 15-foot-high stockade wall and two gates. Nineteen feet inside the stockade was the "deadline," marked by a simple post and rail fence. Guards stationed in sentry boxes shot anyone who crossed this line. The stockade was expanded to 26½ acres in July, but POWs continued to arrive, and by August over 32,000 struggled to survive in what the men called "hell on earth."

Today this area is outlined with double rows of white posts. Two sections of the stockade wall have been reconstructed, the north gate and the northeast corner.

Visiting Andersonville

Accessibility

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to

all. For information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or

check our website.

Federal law prohibits firearms in certain facilities in this park, including the National Prisoner of War Museum. Those areas are marked with signs at all public entrances. For firearms regulations check the park website.

Preservation and Safety

Stay on roadways, do not park on grassy areas. • Do not climb on

earthworks. • Do not disturb plants, animals, monuments, buildings,

relics, or artifacts. • Possession or use of metal detectors is

prohibited. • Natural conditions can be hazardous. Wear shoes to

protect against sandspurs in the grass. • Watch for snakes, poison

ivy, and fire ants (red sandy mounds.) • Be alert and observe

posted traffic regulations.

Andersonville National Historic Site is in southwest Georgia, 12 miles north of Americus and 11 miles south of Montezuma on GA 49. No public transportation serves the park.

Andersonville National Cemetery

Andersonville National Cemetery, established July 26, 1865, is a permanent resting place of honor for deceased veterans. The first interments, in February 1864, were soldiers who died in the prison. They are in sections E, F, H, J, and K. By 1868 over 800 more interments in sections B and C—Union soldiers who died in hospitals, other prison camps, and on battlefields of central and southwest Georgia—brought the total burials to over 13,800. Five hundred of these graves are marked "unknown US soldier." Today the cemetery contains over 20,000 interments in 18 sections lettered A through R (no section O), and one memorial section. Sections are in four quadrants separated by cemetery roads.

Please respect graves and funerals that might be in progress. Use the Nationwide Grave Locator, gravelocator.cem.va.gov, to locate burials online.

Please help maintain a reverent atmosphere by following these cemetery regulations:

• Pets are prohibited on landscaped and grassy

areas. Pets on leash are welcome in other parts of the park.

• No jogging, picnicking, or recreation activities.

• Keep voices lowered.

• Place all litter in refuse containers.

• Do not sit on cemetery headstones or monuments.

• Respect the privacy of all funerals.

Source: NPS Brochure (2015)

|

Establishment

Andersonville National Historic Site — October 16, 1970 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History of Camp Douglas Illinois, Union Prison, 1861-1865 (Dennis Kelly, August 1989)

Andersonville: The story of a Civil War prison camp (Raymond F. Baker, 1972)

Andersonville: The story of a Civil War prison camp (Raymond F. Baker, updated 2007)

Archeological Significance of the CCC Camp at Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia Draft (Teresa L. Paglione, 1985)

Cultural Landscape Inventory, Andersonville National Cemetery, Andersonville National Historic Site (1998)

Cultural Landscape Inventory, Andersonville Memorial Landscape, Andersonville National Historic Site (2010)

Cultural Landscape Report, Andersonville National Historic Site, Andersonville, Georgia (Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., John Milner Associates, Inc. and Liz Sargent HLA, June 2015)

Encountering the Complicated Legacy of Andersonville (James A. Percoco, extract from Social Education, Vol. 75 No. 6, 2011, ©National Council for the Social Studies)

Foundation Document, Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia (February 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia (February 2014)

Ground Penetrating Radar Survey of Andersonville National Historic Site (James E. Pomfret, October 2005)

Historic Resource Study, Andersonville National Historic Site, Andersonville, Georgia (Liz Sargent, Deborah Slaton and Tim Penich, June 2018)

Historic Resource Study and Historical Base Map, Andersonville National Historic Site (Edwin C. Bearss, July 31, 1970)

Historic Structure Report: Ladies of the Grand Army of the Republic Chapel, Andersonville National Historic Site (WLA Studio, February 2018)

Historic Structure Report: Providence Spring House and Associated Structures, Andersonville National Historic Site (WLA Studio, July 2022)

Imprisoned at Andersonville: The Diary of Albert Harry Shatzel, May 5, 1964 - September 12, 1864 (Donald F. Danker, ed., extract from Nebraska History, Vol. 38, 1957, ©History Nebraska)

In Plain Sight: African Americans at Andersonville National Historic Site: A Special History Study (Evan Kutzler, Julia Brock, Ann McCleary, Keri Adams, Ronald Bastien and Larry O. Rivers, December 2020)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Andersonville National Historic Site (February 2010)

National Prisoner of War Museum Dedication — April 9, 1998

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Andersonville National Cemetery and Andersonville Prison Park (Andersonville National Historic Site Staff, February 1976)

Researching Andersonville Prisoners, Guards, and Others (Robert S. Davis, Date Unknown)

State of the Park Report, Andersonville National Historic Site, Georgia State of the Park Series No. 15 (2014)

The Ghost That Still Remains: The Tragic Story of Andersonville Prison (Rachel E. Noll, extract from Perspectives in History, Vol. XVI, 2000-2001, ©Northern Kentucky University)

The Prison Camp at Andersonville (William G. Burnett, 1995, ©Eastern National)

ande/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025